Continuing Education Activity

Tethered cord syndrome (TCS) is a stretch-induced clinical constellation arising from tension on the spinal cord due to anchoring to inelastic structures. Tethered cord syndrome may present with neurologic, urologic, musculoskeletal, dermatologic, or gastrointestinal abnormalities and may be congenital or acquired in etiology. Long-term outcomes are favorable with appropriate diagnosis and treatment. This activity reviews the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, evaluation, and treatment of tethered cord syndrome and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating this condition.

Objectives:

- Summarize the pathophysiology of tethered cord syndrome.

- Describe the clinical presentation of tethered cord syndrome.

- Identify the radiographic appearance of tethered cord syndrome.

- Outline the evaluation and treatment/management of tethered cord syndrome.

Introduction

Tethered cord syndrome (TCS) is a well-recognized cause of deterioration in patients with myelomeningocele, with an estimated one-third of patients requiring spinal cord untethering in childhood.[1] Tethered cord syndrome is defined as a stretch-induced clinical constellation arising from tension on the spinal cord due to caudal anchoring to inelastic structures. Inelastic structures restrict vertical movement of the spinal cord and may arise from congenital etiologies, such as myelomeningocele, or acquired etiologies, such as scar formation.[2]

Stretch-induced functional changes to spinal cord function may result in neurologic, urologic, musculoskeletal, or gastrointestinal abnormalities.[3][4] The term "tethered cord syndrome" originates from an article in 1976 authored by Hoffman et al., wherein they describe 31 patients with elongated spinal cords whose symptoms improved following sectioning of the filum terminale.[5]

Etiology

Etiologies for tethered cord syndrome can be divided into congenital and acquired groups. Myelomeningocele is the most common congenital etiology for tethered cord syndrome. TCS can also develop from other congenital etiologies, including dermal sinus tract, lipo-myelomeningocele, fibrous or fibro-adipose filum terminale, and diastematomyelia.[6][7]

Acquired etiologies for tethered cord syndrome include spinal cord tumors and scar formation.[8]

Epidemiology

The rate of myelomeningocele in the United States is between 0.3 and 1.43 per 1,000 live births, with regional differences.[9] The incidence of myelomeningocele has declined because of folate supplementation and improved maternal nutrition, in addition to other factors.[10]

It is estimated that one-third of myelomeningocele patients will require tethered spinal cord release in childhood, with the incidence of symptomatic spinal cord tethering increasing during periods of rapid growth.[8][4]

Pathophysiology

Excessive traction on the spinal cord due to TCS results in impaired spinal cord perfusion, oxidative metabolism, reduced glucose metabolism, and mitochondrial failure with corresponding electrophysiologic changes and neurologic dysfunction.[2]

Following the release of spinal cord traction, the pathophysiologic and electrophysiologic changes can recover, resulting in neurologic improvement.[2][8]

History and Physical

The clinical presentation of tethered cord syndrome is broad and varies with underlying etiology and age at presentation. Children and toddlers commonly present with sensorimotor dysfunction, with the sensory loss occurring in a non-segmental distribution.[11] Pain in the back and lower extremities also presents complaints within this age group.[12]

For patients in late childhood and early teenage years, pain is the predominant presenting symptom, specifically non-dermatomal pain in the lumbosacral region, perineum, and lower extremities.[11] Incontinence and sphincter dysfunction are also common symptoms in this age group.[12][13]

In the adult patient with a history of spina bifida, the clinical presentation is like that of the adolescent, predominantly with pain and sphincter dysfunction, which can be provoked by flexion and extension movements of the lumbosacral spine.[14] For the adult patient without a history of spina bifida, the pain remains the predominant presenting symptom, followed by weakness and urologic dysfunction.[15]

Trauma often leads to symptomatology within this population and may involve major direct trauma to the spine or may be mild from provoking factors such as exercise, pregnancy, childbirth, etc.[11] It is hypothesized that in this subset of patients, the degree of tethering is not significant enough alone to cause symptoms, but the added trauma increases the stress on an already tense spinal cord, ultimately leading to neurologic or urologic deterioration.[12][16]

Patients of all ages may present with urinary sphincter dysfunction, which may present as urinary tract infections without an alternative cause or episodes of incontinence between scheduled straight catheterizations. Bowel dysfunction may also occur, and patients can experience constipation.

Physical examination plays a key role in the diagnosis of tethered cord syndrome. It begins with an examination of the dorsal spine for cutaneous manifestations of spina bifida, as well as the presence of scoliotic deformity.[11] Cutaneous stigmata may be the only evidence of a tethering lesion in the neonate and infant and may include hair tufts, dermal sinuses, hemangiomas, and lipomas.[17][18]

The lower extremities should be examined for orthopedic deformities, which are commonly associated with tethered cord syndrome and may include pes cavus, equinovarus deformity, and hip subluxation. Sphincter disturbances may be difficult to discern in young patients less than one year of age, but anorectal malformation, in addition to lower extremity deformities, should raise suspicion for tethered cord syndrome.[11]

The remainder of the physical examination should include thorough motor, sensory, deep tendon reflexes, and gait assessment. The deep tendon reflexes and muscle tone can be variable.[11] Gait assessment is important and may be affected by spasticity or orthopedic deformities, such as foot deformities or scoliosis.[12]

Evaluation

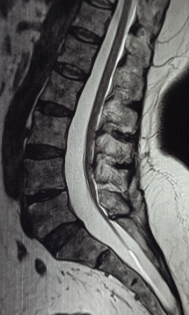

If TCS is suspected based on clinical presentation, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine is the radiographic modality of choice. MRI aids in demonstrating the level of the conus medullaris, identifying lesions associated with the tethered spinal cord, and surgical planning. Despite the variability, the normal level of the conus is at or above the second lumbar level.[19][20]

The thickness of the filum terminale can also be evaluated; a thickness greater than 2 mm can be considered abnormal in children, although this is somewhat controversial.[20][21] Having the patient reposition for a prone, in addition to a supine MRI to demonstrate evidence of motion of the spinal cord, has also been described, with a lack of motion between supine and prone position MRI scans suggesting a tethered spinal cord.[11][22]

MRI can further aid in visualizing the underlying pathology associated with the spinal cord tethering, including myelomeningocele, lipomyelomeningocele, split cord malformation, tumor, etc. Constructive interference in steady state (CISS) MRI sequence may be used in indeterminate cases as it has been shown to have superior sensitivity to T2-weighted MRI sequences.[23] In addition to MRI, standing scoliosis X-rays and computed tomography (CT) scans can also be considered to further evaluate scoliosis if present.

In shunted hydrocephalus, the evaluation of TCS should begin with an assessment of shunt function, as shunt malfunction can have a similar presentation. A malfunctioning shunt should be revised, and the patient should be reassessed several weeks post-operatively. If there is no clinical improvement following shunt revision, then TCS should be strongly considered.

Urodynamic testing plays an important role in establishing sphincter dysfunction. Relevant parameters in evaluating a neurogenic bladder include bladder compliance, total bladder capacity and pressure, uninhibited contractions, leak point pressure, sensation, and electromyogram activity.[24][25]

Detrusor hyperreflexia is the most common finding, but dyssynergia, decreased bladder compliance, and decreased sensation can also occur.[11] Formal urodynamic testing may also be useful for serving as a marker to document stability or improvement of function following an untethering surgery.[11]

Treatment / Management

Surgical intervention is indicated for tethered cord syndrome if clinical signs and symptoms are present in conjunction with radiographic findings.

The surgical steps for spinal cord untethering begin with a midline skin incision corresponding to the level of the conus at the filum terminale junction.[26] The paraspinal muscles are subsequently separated from the spinous processes and laminae medial to the articular facets of one or two levels. A laminectomy or laminoplasty may be performed with attention to avoid violating the facet joints laterally.

Once the dura is exposed, a midline incision of the dura and arachnoid membrane is made, and stay stitches are placed at the dural edges. Gentle caudal dissection of the conus medullaris proceeds until the exit of the most caudal coccygeal nerve root(s) is identified with the filum terminale beginning caudally to the most caudal coccygeal nerve root.

Once the filum terminale is identified, any adherent coccygeal or lower sacral nerves are dissected from the filum terminale. Once cleanly dissected, the filum terminale is cauterized and resected approximately 5 mm below the conus-filum junction. If there is a question as to whether the filum terminale is completely freed of adherent nerve roots, nerve root stimulation studies can be employed intraoperatively.[26]

Following untethering and inspection of nerve roots, the dura is closed in a water-tight fashion, which can be confirmed by asking anesthesia to provide a Valsalva maneuver. Sealants can be applied over the dural closure, including synthetic sealants, dural substitutes, or a combination of the two. If a laminoplasty is performed rather than a laminectomy, absorbable or titanium plates can be used to fix the lamina back into place. Once hemostasis has been achieved, the incision can be closed in a multilayer closure. Intraoperative electrophysiologic monitoring can be considered as it has been found to reduce perioperative surgical risk.[27]

Recently, in a small series, minimally invasive tubular tethered cord release has been proposed as a safe and viable alternative to the traditional open approach with a statistically significant decrease in blood loss and length of hospitalization.[28] In patients with chronic intractable neuropathic mediated pain secondary to recurrent tethered cord syndrome, dorsal spinal cord stimulation (SCS) is a potentially effective treatment option.[29][30]

Differential Diagnosis

Given the broad clinical presentation of tethered cord syndrome involving multiple systemic manifestations, including neurologic, orthopedic, dermatologic, and urologic, the differential diagnosis for the presenting signs/symptoms of tethered cord syndrome is vast and beyond the scope of this review article.

Radiographically, the differential diagnosis for the underlying etiology contributing to the tethered cord syndrome can be thought of similarly to the underlying etiologies of tethered cord syndrome, which include congenital and acquired etiologies. The differential diagnosis for the congenital etiologies of tethered cord syndrome includes dermal sinus tract, myelomeningocele, lipomyelomeningocele, fibrous or fibro-adipose filum terminale, and diastematomyelia.[8]

The differential diagnosis for the acquired etiologies of tethered cord syndrome includes spinal cord tumors and scar formation from prior surgical intervention, infection, or hemorrhage.

Prognosis

Long-term outcomes following spinal cord untethering are favorable.[31] One study found that weakness improved in 70%, stabilized in 28% and deteriorated in 2%, gait improved in 79%, stabilized in 19% and worsened in 3%, spasticity improved in 63% and stabilized in 37%, pain improved in nearly 100%, and lastly, bladder function improved in 67%, stabilized in 30% and deteriorated in 3%.[31]

If bladder dysfunction is present, this continues into the immediate postoperative period in most children due to temporary neurapraxia.[32] This can last for several days to even months.[33] Most patients recover their ability to void within the first 1 or 2 months postoperatively.[32]

A subsequent spinal cord untethering was required in about 30% of patients who had previously undergone tethered spinal cord release.[31] Of those patients requiring a second tethered cord release, 39% required a third, and 13% a fourth tethered spinal cord release.[31]

An interesting phenomenon following spinal cord untethering is a statistically significant gain in height-for-age percentiles, which may be more significant in older children (≥ 5 years of age).[34]

Complications

Complications following spinal cord untethering are uncommon, with neurologic or urologic worsening occurring in around 3 to 5% of patients.[31] Post-operative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks and symptomatic pseudomeningoceles occur infrequently and, if present, should raise suspicion of an occult CSF shunt malfunction.[31]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Post-operatively, patients commonly stay 1 or 2 nights in the hospital. A brief period of flat bed rest, typically overnight, during the initial postoperative day can be considered to reduce stress on the dural closure. Ambulatory postoperative referrals to occupational and/or physical therapies may benefit bowel/bladder dysfunction and limb contractures.

Consultations

An evaluation by neurological surgery is recommended for all patients with suspected TCS. Patients may additionally benefit from an orthopedic surgery consultation if limb abnormalities or scoliosis are present. Urology consultation may also be required if urodynamic testing is pursued.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Tethered cord syndrome is a well-recognized cause of deterioration in the myelomeningocele population, with an estimated one-third of patients requiring spinal cord untethering in childhood.[1]

Tethered cord syndrome can have multiple systemic manifestations, including neurologic, urologic, dermatologic, and orthopedic. Long-term outcomes following tethered spinal cord release are favorable, with improvements in pain, weakness, gait, spasticity, and bladder function observed.[31] In a minority of patients, recurrent spinal cord tethering may occur, requiring additional tethered spinal cord release surgeries.[31]

Surgical complications are uncommon but can occur, with neurologic or urologic worsening occurring in around 3 to 5% of patients.[31]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Tethered cord syndrome may present with a collection of systemic manifestations. Management of tethered cord syndrome requires a multidisciplinary and interprofessional approach, including nursing, physical/occupational therapy, pediatrics/primary care medicine, radiation technology, radiology, orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, and urology. Only by working as an interprofessional team, with open communication between team members and accurate record keeping, can proper recognition, evaluation, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation occur. [Level 5]