Continuing Education Activity

Foreign body aspiration is the fourth leading cause of death in preschool and younger age children and accounts for a significant number of emergency department visits in the United States and worldwide. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of airway foreign bodies and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the recognition and management of airway foreign bodies.

Objectives:

- Review the pathophysiologic basis of airway foreign bodies.

- Outline the expected history and physical findings for a patient with an airway foreign body.

- Summarize the treatment options available for airway foreign bodies.

- Describe the need for an interprofessional team approach to caring for a patient with an airway foreign body.

Introduction

The presentation of foreign body aspiration in the emergency department varies greatly and can suffer from incorrect or delayed diagnosis. Factors affecting the acuity of the problem include the object that is aspirated, the location of the aspirated object, whether the event was witnessed, the age of the patient, as well as the timeframe in which aspiration occurred. Acute upper airway compromise may present with classic symptoms of choking including and significant respiratory distress, while a more distal obstruction may present with chronic mild wheezing, cough, a complaint of discomfort, or general shortness of breath, and may mimic asthma or other less acute respiratory illnesses.

Foreign body aspiration is the fourth leading cause of death in preschool and younger age children.[1] It accounts for a significant number of emergency department visits in the United States. As such, it is a leading concern for both prevention and public health as well as critical recognition and treatment. The Consumer Product Safety Commission placed restrictions on items that may confer a choking hazard, and in 1973, federal regulation 15 CFR 1501 introduced the Small Parts Test Fixture which provides measurements for toys designed for children three years and younger.[2]

Although several federal guidelines have been implemented to reduce choking in young children, including package labeling with warnings for small parts and warnings on television and internet advertisements to inform the public of the choking hazards of toys. In the United States, no regulations exist on food items with a potential risk for choking, though many aspirations are organic food material. Peanuts, seeds, and fruits with round shapes are the most often aspirated food in children, while hotdogs and candy account for a majority of deaths from choking.[3] Public education of parents, babysitters, teachers, and caregivers remains an essential factor in preventing airway foreign body aspiration. New onset wheezing, coughing, drooling, voice changes, or posturing should alert practitioners and parents to the possibility of foreign body aspiration, even if the event itself was unwitnessed.

Etiology

Upon aspiration of a foreign body into the larynx or proximal trachea, there is always the potential for respiratory compromise or for further inhalation into the distal airways causing subacute symptoms including shortness of breath, wheezing, or coughing. Any object that can be placed into the mouth can potentially be aspirated. This is of particular concern in infants and young children who explore and interact with their environment by placing objects into their mouth; parental vigilance regarding which objects are available to an unsupervised child is paramount. Similarly, infants' and young children's swallowing coordination has not fully developed, and there is a proclivity to inhale or aspirate foods when eating. Peanuts are the most frequently ingested object in the west, with hotdogs causing the most mortality. Male children are more likely to aspirate than female children.[3] Food or other objects with a smooth, round shape are the highest risk for aspiration (nuts, beans, grapes, hotdogs/sausages, etc), and a primary prevention strategy is to prepare such foods in a way so as to change this shape to something more angular and easier to chew and swallow (by quartering grapes, for example).

Epidemiology

Children, males more often than females, as well as developmentally delayed individuals, are more likely to aspirate foreign bodies, though the elderly are also at risk. In the west, food objects are most commonly aspirated, with peanuts being the most commonly aspirated food, followed by hotdogs and hard candy. Outside of food, other smooth and round objects like marbles and rubber balls are often aspirated. The lack of molars to chew food is also a contributing factor in children.[3]

Statistical data predominantly derives from single-center studies. Larger cohorts and nationwide analysis have only recently bee compiled to analyze broader data.[7] These studies estimate the incidence of foreign-body airway obstruction (FBAO) to be 0.66 per one hundred thousand.[8] In the USA, seventeen thousand emergency visits in children under 14 years of age were linked to foreign bodies inhalation in 2000.[9] Foreign body aspiration is the number one cause of accidental infantile deaths, and the fourth most common cause of death among preschool children less than five years of age.[10]

Airway foreign bodies have unique demography; 80% of cases are younger than three years of age, with a peak frequency occurring in the one- to two-year-old age group.[11] In a retrospective case series of 81 cases, Asif et al. reported children under five years old aspirate 77.8% of foreign bodies, 16% by children between five and fifteen years old, and 6.2% by those above fifteen years old. Similarly, Reilly et al. highlighted children four-years-old or younger are more vulnerable to inhaling foreign bodies as they are driven by oral exploration using their molar-free mouths and their lack of well-coordinated swallowing reflex.[12]

Pathophysiology

Complete obstruction of the glottic or tracheal airway will lead to audible and visible immediate choking, respiratory distress, cyanosis, and death if not rapidly treated. Complete obstruction of a mainstem bronchus or intermediate bronchus can lead to distal infection with time but maybe surprisingly asymptomatic in the case of a mainstem bronchial obstruction. Partial obstruction may lead to inflammation of local tissue with variable degrees of dyspnea, SOB, wheezing, coughing, or other symptoms depending on the airway structure involved. As a general rule, the more proximal the airway, the more severe, rapid, and evident symptoms will be. Food may lead to more inflammatory effects than metal or plastic objects, as they are organic and may swell, leading to ongoing more severe obstruction.[3] Medications such as iron tablets have led to distal airway stenosis and severe airway inflammation.[4]

History and Physical

History of aspiration or suspected aspiration is often sufficient to warrant a full workup including a rigid bronchoscopy.

Aspiration may present in different ways. Acute large airway obstruction presents with severe obvious clinical distress, stridor, choking signs, and drooling. Such patients should not be unduly agitated by physicians or other staff and should be taken emergently to the operating room for a formal airway examination with rigid bronchoscopy and preparations ready for emergent tracheostomy. Avoid instrumenting the airway with mouth exams or endoscopes in the Emergency Department. Even if such a patient is not found to have a foreign body, they are in respiratory distress with an unknown, unstable airway and should be further evaluated under the safest conditions possible: in an operating room.

Chronic shortness of breath can be related to aspiration of a foreign body, especially in children and developmentally delayed individuals who are unable to articulate the event reliably. This is more likely to be in the smaller, more distal airways and symptoms can relate either to complete occlusion of a terminal bronchus and development of pneumonia or to partial obstruction leading to wheezing, coughing, stridor, and progressive symptoms as the surrounding respiratory epithelium becomes more reactive and edematous. The patient may have several weeks of coughing, shortness of breath, or even complain of chest discomfort. Such patients may present weeks to months later, and the initial aspiration event may have been unknown or forgotten by patients and families.

Airway anatomy in children differs from anatomy in adults. The narrowest portion of the pediatric airway is the cricoid, while in adults the narrowest portion is the glottis. Thus particles may be large enough to be aspirated past the vocal cords (glottis) in children only to become lodged in the subglottis at the area of the cricoid, to potentially devastating effect.

When considering aspiration of foreign objects, children have a slight predominance for aspiration into the right mainstem bronchus, but this proclivity increases with age owing to a more vertical orientation of the right mainstem in adults that parallels the orientation of the trachea - it becomes the most dependent and direct portion of the adult airway.

The physical exam may show tripod posturing, drooling, stridor, or wheezing in large airway obstruction as detailed above. History may be suggestive of aspiration, even from several weeks prior, in smaller airway aspiration and symptoms may be more vague and subtle, including focal wheezing or asthma-type symptoms. Patients with such symptoms warrant a formal airway evaluation via bronchoscopy if they fail to respond to an appropriate treatment course for infectious causes and reactive airway disease.[3]

Evaluation

As stated above, if the patient is in extremis or uncooperative in a young child, do not image or otherwise aggravate the patient. Proceed to the operating room immediately for a controlled airway examination under anesthesia with rigid bronchoscopy and emergency tracheostomy supplies available.

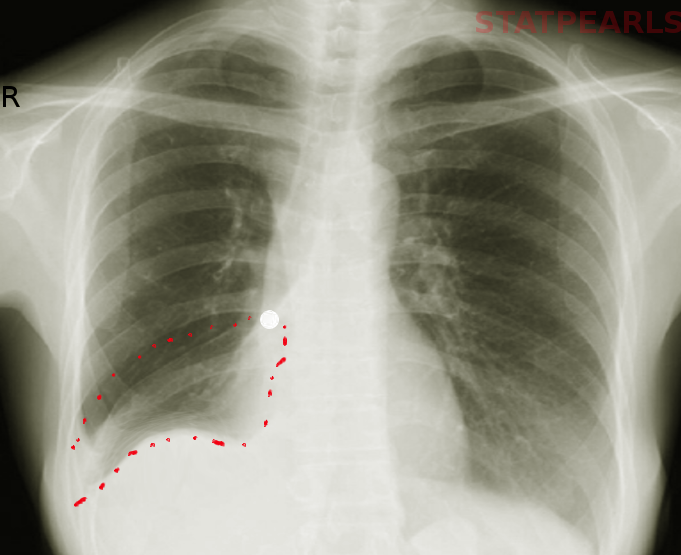

If the patient is stable and cooperative, evaluation can begin with chest X-rays, PA, and lateral inspiratory-expiratory films. Unilateral expansion with diaphragm flattening of the affected side with mediastinal pushing away will indicate obstruction on that side. Air trapping can also be demonstrated on inspiratory-expiratory films indicative of a ball-valve effect due to a foreign body obstruction. If the foreign body is radiopaque, these can also identify and localize the object. Obtain IV access with bloodwork including complete blood count and electrolytes in preparation for a possible general anesthetic. A routine venous blood gas is of little use and should be avoided. If the patient is stable and cooperative, a head and neck exam with or without flexible laryngoscopy can elucidate other mimicking conditions such as tonsillitis or peritonsillar abscess, which can then be addressed. Auscultation in the primary lung fields can demonstrate wheezing or focal consolidations when paired with percussion and tactile fremitus evaluation. Computed tomography should be reserved for only the most stable and comfortable patients in whom foreign body is very low on the differential diagnosis. An airway emergency in a radiology suite carries a high mortality. [5]

Treatment / Management

For an active upper airway obstruction, airway control is paramount. Do NOT blindly sweep the airway, perform direct visualization of the airway with any sort of oral instrument or tongue blade, or attempt extraction with Magill forceps unless the patient is adult, awake, alert, consenting to the procedure, and in no discomfort whatsoever. In the VAST majority of patients, such maneuvers are better performed in the operating room under more controllable circumstances. Intubating past the obstruction or forcing the blockage into one of the mainstem bronchi may be required, and these maneuvers are best discovered to be necessary, and far more successfully carried out, in a fully-equipped operating room rather than an Emergency Department.

Emergent cricothyroidotomy may be indicated if there is no other avenue to ventilate the patient and they present in respiratory arrest.

For a possible lower airway obstruction, a good history and physical exam are always important, particularly regarding any unsupervised time of a child around small objects, a witnessed aspiration or choking event, or a new onset of cough or other respiratory symptoms that cannot be otherwise explained. If the patient has been treated and symptoms have not resolved, a formal interventional airway examination is warranted. The definitive treatment is rigid bronchoscopy, and at some centers, rigid bronchoscopy will be performed based on history or suspicion alone as up to 15% of aspirations have a normal physical exam and imaging.[1]

Definitive management of known radiopaque or suspected radiolucent foreign body is rigid bronchoscopy under general anesthesia. If the object has acutely been aspirated then retrieval and normal post-op recommendations are sufficient and may include oral or inhaled corticosteroids. If there have been clinical signs of infection, then antibiotic treatment for post-obstructive infection can be initiated at that time.[6]

Differential Diagnosis

Diseases that may present with clinical findings similar to foreign body aspiration are asthma, pneumonia, tuberculosis, epiglottitis, retropharyngeal abscess, peritonsillar abscess, postviral pericarditis or pleuritis, and bronchiolitis. Traumatic injuries with localized pulmonary, airway, or even diaphragmatic injury may present similarly to foreign body aspiration. From this list, one can see the differential is very broad due to the plethora of presenting complaints and their breadth is severity. This is one of the challenges of airway foreign body diagnosis (particularly in the pediatric or otherwise non-communicative population).[7]

Prognosis

In children with foreign body aspiration, the prognosis is good if removed early and without complications. Most patients who present responsive to an Emergency Department after foreign body aspiration have a good outcome. Acute aspiration of a larger object that obstructs the trachea or proximal airway can have very dire consequences. In a study of 94 children who all presented three days after aspiration, all recovered fully from any complications aside from one who died of respiratory failure.[8]

Complications

During management, there is an approximately 25% complication rate in early intervention for aspirated foreign body, and the vast majority of these are mild. Late intervention brings more severe complications such as hypoxia or anoxic brain injury (particularly with tracheal or mainstem bronchus obstruction), bronchial injury, airway stenosis, abscess formation, pneumothorax. These are also rare, but significant. Aside from an unfortunate (very small) minority of cases that will end in death from respiratory compromise, children will likely recover with treatment for these delayed complications.[8]

Consultations

- Interventional pulmonology, otolaryngology, cardiothoracic surgery

Deterrence and Patient Education

- Consumer Product Safety Commission

- Federal regulations on packaging and warnings

- Education of parents and others who may supervise children on the risks of hard round food items - to watch and encourage slow mastication to ensure safe eating habits and supervision of meals and snacks for young children

Pearls and Other Issues

- Peanuts are the most commonly aspirated foods, followed most often by items like marbles, and small rubber balls

- Hotdogs and hard candies are the most common food items, and latex balloons are the most common non-food items to cause fatal aspiration

- Rapid diagnosis and retrieval lead to the best outcomes in these patients

- Less likely to have upper airway (laryngeal or tracheal) obstruction than lower, however, emergent airway control is required with upper obstruction due to the potential for complete ventilatory compromise

- Lower airway obstruction necessitates a good history and physical especially in children and developmentally delayed individuals, and suspicion for foreign body aspiration - inspiratory-expiratory chest x-ray, pre-op lab work, otolaryngology consultation, and antibiotics based on clinical picture and timeframe

- Definitive management of known radiopaque or suspected radiolucent foreign body is rigid bronchoscopy under anesthesia.

- If the object has acutely been aspirated then retrieval and normal post-op recommendations are sufficient

- If there have been clinical signs of infection, then antibiotic treatment for post-obstructive infection can be initiated

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Foreign body aspiration frequently creates a diagnostic dilemma. Such patients may exhibit non-specific signs and symptoms such as a cough, shortness of breath without a medical history or diagnosed medical problems, unclear-onset, and vague discomfort. The cause of these complaints may be due to an infectious, allergic, traumatic, reactive, or foreign body etiology. While physical examination may reveal that the patient has a focal lung finding, the cause will likely correlate with a history of possible aspiration.

While the pulmonologist is almost always involved in the care of patients with a foreign body aspiration, it is essential to consult with an interprofessional team of specialists that include an otolaryngologist, and possibly a cardiothoracic surgeon, depending on the suspected site of the aspirated foreign body. The nurses are also vital members of the interprofessional group as they will monitor the patient's vital signs, help with family members, and keep patients and family calm. In the postoperative period for pain, possible infection, and possible airway lesions; the pharmacist can ensure that the patient is taking the right analgesics, bronchodilators, and appropriate antibiotics. The radiologist also plays a crucial role in delineating the cause. Without a proper history, the radiologist may not be sure what to look for or what additional radiologic exams may be necessary.

The outcomes of a foreign body aspiration are usually good. However, to optimize outcomes, prompt recognition of the individual roles of an interprofessional group of specialists is recommended.[9][10]