Continuing Education Activity

Anticonvulsants, or antiepileptics, are an ever-growing class of medications that act through multiple different mechanisms to control seizures. Antiepileptic toxicity commonly presents with a triad of symptoms, which include central nervous system depression, ataxia, and nystagmus. Certain antiepileptic agents are associated with more specific toxicities, including seizures. This activity examines when anticonvulsant toxicity should be considered on differential diagnosis and how to properly evaluate it. This activity highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the mode of toxicity of anti-convulsants.

- Describe the presentation of patients with anticonvulsant toxicity.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for anticonvulsant toxicity.

- Explain the modalities to improve care coordination among interprofessional team members in order to improve outcomes for patients affected by anticonvulsant toxicity.

Introduction

Anticonvulsants, or antiepileptics, are an ever-growing class of medications that act through multiple different mechanisms to control seizures — antiepileptic toxicity commonly presents with a triad of symptoms, which includes central nervous system (CNS) depression, ataxia, and nystagmus. However, various antiepileptic agents have associations with more specific toxicities, including seizures, for which practitioners need to be aware.

In general, seizures result from excessive neuronal firing related to an imbalance of inhibitory and excitatory activity in the brain. While there is a multitude of different antiepileptic agents used in practice today, they all primarily act via interference with one or more of several cellular mechanisms believed to cause seizures. Mechanisms of action include inhibition of sodium channels, inhibition of calcium channels, inhibition of the excitatory interaction between glutamate and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), enhancement of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity, and inhibition of neuronal exocytosis via interaction with synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A). While excessive effects on these pathways can contribute to toxicity, other specific medication properties may also contribute.

Etiology

Anticonvulsant toxicity commonly occurs following acute ingestion or chronic supratherapeutic exposure. Acute ingestion may include suicide attempts, inadvertent pediatric ingestions, and now becoming more frequent is medication misuse. Gabapentin misuse is growing more common. Chronic supratherapeutic exposure may be related to inappropriate dosing or unintended medication interactions that can interfere with metabolism or clearance, thus raising serum concentrations. Numerous xenobiotics can interfere with antiepileptic activity, and conducting a medication interaction search should always be required when caring for patients on multiple medications. Extended-release formulations may also contribute to toxicity in certain situations.

Epidemiology

Patients prescribed anticonvulsants for seizure disorders are most at risk for toxicity. Case reviews have shown that from 3 to 8% of suicide attempts involved ingestion of anticonvulsant medications, either taken solely or in combination with other agents. Also, patients with chronic pain and various psychiatric diagnoses are at risk because many antiepileptic agents also have indications (both approved and off-label) for pain management and mood stabilization. Gabapentin is often used for chronic and neuropathic pain, in addition to mood stabilization, and has notable abuse potential. Other anticonvulsants used for mood stabilization, such as valproic acid, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine, are often prescribed to patients who are at risk for a suicide attempt, and these particular agents can be lethal in overdose.

Pathophysiology

Anticonvulsants act primarily through one, or a combination of five, mechanisms. These mechanisms and common medications that act on these mechanisms include[1]:

- Inhibition of sodium channels: carbamazepine, lacosamide, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, valproic acid, topiramate, zonisamide

- Inhibition of calcium conductance: ethosuximide, zonisamide, valproic acid (VPA), pregabalin, gabapentin

- Inhibition of excitatory neurotransmitters (NMDA): perampanel, felbamate, lamotrigine, topiramate

- Stimulation of Inhibitory neurotransmitter (GABA): benzodiazepines, phenobarbital, tiagabine, vigabatrin

- Interaction with SV2A proteins: levetiracetam

Toxicokinetics

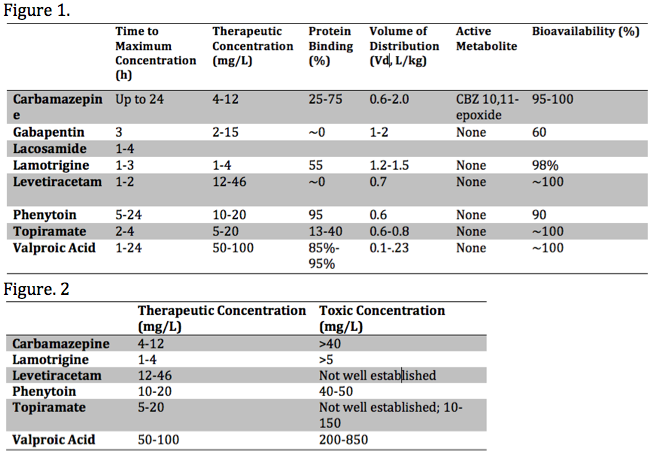

Each anticonvulsant medication has unique pharmacokinetic properties, including the time to peak concentration, therapeutic range, bioavailability, the presence of toxic metabolite(s), as well as the volume of distribution (Vd) and protein-binding. These various properties influence the toxic presentation, evaluation, and treatment. These properties are summarized in the media below[2][3][4]:

Important properties playing a role in the toxicity of anticonvulsants are metabolism and elimination. Here we will primarily focus on the CYP450 enzyme system, glucuronidation and associated features of specific agents. The cytochrome P450 system (CYP450) is a common pathway among many antiepileptic agents. For example, carbamazepine undergoes metabolism by CYP450 enzyme CYP3A4[5]. Carbamazepine toxicity can be precipitated by agents that inhibit the CYP3A4 enzyme, such as allopurinol, diltiazem, fluoxetine, isoniazid & valproic acid. Agents that induce CYP3A4, thus decreasing carbamazepine levels and increasing its active metabolite, carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide (CBZ-10,11-epoxide), include corticosteroids, omeprazole, phenytoin & St. Johns Wart. Other medications and anticonvulsants, including valproic acid, can inhibit epoxide hydrolase and cause toxic serum levels of CBZ-10,11-epoxide. Carbamazepine is also a potent CYP3A4 inducer and can cause decreased serum levels of some anticonvulsants, such as valproic acid and phenytoin, and other medications, such as oral contraceptives. Of note, gabapentin and lamotrigine do not get metabolized by a CYP450 enzymatic pathway and have no significant interactions with other antiepileptics.

Glucuronidation is also a common pathway of metabolism. Carbamazepine and phenytoin induce glucuronidation and can lower serum concentration of lamotrigine. Valproic acid competes with lamotrigine in this same step.

Valproic acid is metabolized 50-80% by glucuronidation. Valproic acid also undergoes hepatic metabolism via oxidation, primarily through carnitine-dependent ß-oxidation in the mitochondria and oxidation in the endoplasmic reticulum. After valproic acid is taken up into the liver, it transfers from acetyl-CoA to carnitine to transfer into the mitochondria through carnitine translocase. It then transfers back to acetyl-CoA to undergo ß-oxidation. Carnitine-bound valproic acid can also undergo renal elimination. When carnitine depletes via ß-oxidation, valproic acid undergoes metabolism via an alternate pathway, beta-oxidation, which takes place in the endoplasmic reticulum instead of the mitochondria. The products of beta-oxidation include 4-en-VPA and propionate. 4-en-VPA is hepatotoxic and leads to inhibition of carbamoylphosphate synthase 1, which is needed for incorporating ammonia into the production of urea. This enzymatic inhibition is why serum ammonia concentrations can elevate in valproic acid toxicity. Hyperammonemia is known to cause encephalopathy and injury to other tissues.

Comprehension of these interactions is crucial to the management of anticonvulsant toxicity.[6]

History and Physical

A thorough history and physical exam can be challenging to obtain in the setting of anticonvulsant toxicity. The patient may be unwilling to give the factual history in the setting of non-accidental overdose or unable if significant time has passed since ingestion; also the patient may be unable to provide history due to age or change in mental status. There are, however, similarities in patient populations and the presentation of these patients that can aid in identifying the ingested medication. There are also specific physical exam findings that can assist in identifying agents and suspected quantities ingested. Common exam findings include central nervous system depression, nystagmus, and ataxia.[7]

There are also signs and symptoms specific to the mechanisms of action of these various anticonvulsants. Medications that act on multiple pathways can present with signs & symptoms affecting multiple organ systems including cardiac, hepatic, neurologic, metabolic (hyponatremia), renal systems, making a thorough history, physical exam and review of prescribed medications critical.

Symptoms seen in anticonvulsant toxicity can include confusion, nystagmus, ataxia lethargy, coma, respiratory depression, and death. Central nervous system (CNS) depression is most common in medications that act by regulating excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters but is a potential feature with the toxicity of most anticonvulsants. Medications that block sodium channels can present with cardiac conduction abnormalities, as well as acute blood pressure and heart rate changes that include sinus bradycardia, sinus tachycardia, and hypotension. These medications may include carbamazepine, lacosamide, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, valproic acid, topiramate, and zonisamide.[8]

Certain anticonvulsants can also induce seizures and dysrhythmias. Some of these agents are associated with sodium channel inhibition and include carbamazepine, lamotrigine and possibly zonisamide. Carbamazepine can also increase sensitivity to antidiuretic hormone receptors and induce hyponatremia, thus further increasing the risk of seizure through metabolic derangement.[9][10]

DRESS syndrome, or Drug Reaction with Systemic Symptoms, is a drug-induced reaction. The syndrome usually involves skin rash eosinophilia and other organ system involvement, most commonly liver or kidney. Carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and valproic acid and other aromatic anticonvulsants are well known to cause DRESS syndrome. Delayed treatment of DRESS syndrome can lead to end-stage organ disease and toxic epidermal necrosis. Obtaining skin biopsies should be a diagnostic exam in the setting of suspected DRESS. Patients with DRESS syndrome should be admitted to the hospital and started on systemic corticosteroids (1kg/mg/day). IV Immunoglobulin is also a treatment option that has been successful.[11][12]

Evaluation

Patients with signs and symptoms of toxicity should have a thorough evaluation specific to the agent of concern. In patients who overdose, the recommendation is that they have routine screening tests that include an electrocardiogram, a basic metabolic panel, acetaminophen concentration, and a pregnancy test if the patient is a female of child-bearing age. In the undifferentiated patient, additional tests may include a complete blood count, ethanol and salicylate concentrations and computed tomography of the brain. Urine drug screens are of little use and do not change practice. History and physical exam should guide any further testing.

Cardiac and respiratory monitoring is also essential in the evaluation of anticonvulsant toxicity. Continuous monitoring of vital signs and serial electrocardiograms are recommended to assess for QRS and QTc prolongation. For patients presenting following ingestion of a known anticonvulsant, serum concentrations should be measured. Obtaining serum concentrations may require sending the blood sample to another facility with resulting delay, and should not be relied upon to affect clinical decisions.

Assessment of serum phenytoin requires consideration of protein-binding properties. Phenytoin is primarily bound to albumin. Toxicity can present with normal serum concentrations in the presence of hypoalbuminemia, usually in the setting of malnourishment. The revised Winter-Tozer equation approximates the serum concentration considering serum albumin concentrations.[13]

- [Corrected Phenytoin (mg/L)]=[Measured Phenytoin (mg/L)]/{[0.25*Albumin (g/dl)]+0.1}

Serial testing of serum concentrations should be obtained every four hours in the overdose setting. In the early assessment, concentrations may be needed as frequently as every two hours due to erratic absorption. Many laboratories have cut-off concentrations for measurement and dilution may be necessary to obtain an accurate concentration. Serum concentrations alone should guide therapy.[6]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of anticonvulsant toxicity depends on the agent and quantity ingested and is primarily supportive, with respiratory and hemodynamic support and intravenous hydration. Other treatments may include activated charcoal, benzodiazepines, hemodialysis, charcoal hemoperfusion, sodium bicarbonate, and specific antidotes. Many patients who overdose recover uneventfully, particularly in the setting of toxicity from gabapentin and levetiracetam.[14]

Activated charcoal may be given early if the mental status is normal.[15] Multidose activated charcoal (MDAC) has shown some benefit for enhanced elimination of carbamazepine and phenytoin via gut dialysis, but may be limited by depressed mental status. Initial dosing of AC is 50-100g in adults & 1g/kg in pediatric patients under five years of age. For MDAC the recommended dose is 12.5 g/h.

Benzodiazepines are the primary treatment for seizures and other autonomic instability. Benzodiazepines should be dosed until seizures or subside, or autonomic instability improves.

For antiepileptic agents associated with sodium channel blockade, sodium bicarbonate should be administered at 50-100 mEq PRN for QRS interval greater than 100-120 milliseconds on serial electrocardiograms. QRS prolongation is associated with seizures when greater than 100 milliseconds and dysrhythmias when greater than 160 milliseconds. When administering sodium bicarbonate in this scenario, gaol pH should be 7.45-7.55, and goal sodium is 145-155 mEq/L. Each administration of sodium bicarbonate should be followed by a repeat ECG to assess response, with venous or arterial blood gas and basic metabolic panel to assess goal parameters. Hyperventilation in the intubated patient may also be utilized to alkalinize serum further. Hypertonic sodium can be used adjunctively if serum pH is at goal. If both pH and sodium are at maximum goal and QRS is still prolonged in the ill patient, lidocaine may be utilized for additional therapy as its sodium channel inhibition is fast-acting and may serve to facilitate displacement of the toxin.

While not truly an antidote, levocarnitine is used in valproic acid toxicity in the setting of encephalopathy, significant hyperammonemia or hepatotoxicity. Dosing is 100 mg/kg (maximum of 6 g) IV loading dose over 30 minutes, followed by maintenance dosing of 50 mg/kg (maximum 3 g) IV over 10-15 minutes every 6 hours [16]. Levocarnitine serves to facilitate ß-oxidation and renal elimination of valproic acid.

Enhanced elimination techniques may be considered in the severely ill patient although they are rarely necessary. Hemodialysis and hemoperfusion may prove effective treatment options but are seldom indicated.[17] Hemoperfusion involves perfusing blood through a filter, usually activated charcoal, to remove toxins. Hemoperfusion has associations with multiple side effects including thrombocytopenia, hypocalcemia, coagulopathy. Hemodialysis involves purifying the blood by diffusing solutes through a semipermeable membrane. Hemodialysis has fewer side effects than hemoperfusion, and multiple studies have found it to be as efficacious as charcoal hemoperfusion in the removal of multiple anticonvulsants including carbamazepine.

Hemodialysis is more efficacious than MDAC for carbamazepine toxicity. The most likely indication for dialysis is severe valproic acid toxicity with a serum concentration greater than 850 mg/L, in which significant morbidity and mortality may occur. Over 850 mg/L, protein-binding is saturated, and valproic acid is amenable to dialysis.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of anticonvulsant toxicity includes other etiologies of CNS depression and cardiovascular abnormalities including CVA, ICH, infection, or ACS. Other important toxicological considerations for CNS depression include opioid analgesics and sedative-hypnotics.

Prognosis

Patients often recover fully from anticonvulsant toxicity. Cardiac and neurologic complications may lead to permanent debilitating conditions if resuscitation is not available. This can cause significant morbidity and mortality.

Consultations

All patients presenting with acute or chronic toxicity should be managed in consultation with a medical toxicologist or poison center and a neurologist.

Pearls and Other Issues

- A thorough history and physical exam is vital to diagnosis and treatment

- The triad of anticonvulsants toxicity is central nervous system depression, nystagmus, and ataxia.

- Many agents are fairly benign in the setting of toxicity, but severe toxicity may be associated with seizure, coma & death.

- Benzodiazepines are the primary treatment for seizures in the setting of antiepileptic toxicity.

- Some anticonvulsants can cause seizures and dysrhythmias in overdose, including carbamazepine and lamotrigine, and serial ECGs are indicated to monitor for associated QRS prolongation, and sodium bicarbonate should be administered for QRS greater than 100 ms.

- It is essential to consider the metabolic profile of antiepileptic agents and how they interact with other medications.

- Activated charcoal is sometimes an effective therapy for an acute overdose on anticonvulsants

- L-carnitine is recommended for valproic acid toxicity associated with encephalopathy, hyperammonemia or hepatotoxicity.

- Hemodialysis is recommended in valproic acid toxicity at a serum concentration of greater than 850 mg/L

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Anticonvulsant toxicity requires an interprofessional team including nurses, laboratory technicians, pharmacists, emergency physicians, and medical toxicologists. Patients often present to emergency departments and can present with unstable vital signs. Recognition by triage nurses and prompt intervention by an emergency physician is imperative. The assigned nurse should monitor the patient for untoward changes in vital signs and report to the clinical team. The pharmacist should assist with medication reconciliation and provide appropriate dosing for antidotes. Initial emergency interventions by the interprofessional team include:

- Obtaining a thorough history and drug history whenever possible

- Recognition of toxidromes when present

- Stabilization including hemodynamic and airway support

- Laboratory workup including electrolytes, blood count, drug levels, imaging as appropriate

- Administration of antidotes when indicated

- Consultation with a toxicologist, critical care team and radiology

Treatment of anticonvulsant toxicity usually involves admission to the hospital. Consultation with nephrology may be required as Dialysis may be necessary. Mental health consult is also crucial as toxicity is often secondary to intentional ingestion and suicide attempt. Working as an interprofessional team is a requirement to decrease morbidity and mortality in anticonvulsant toxicity.