Learning Outcome

- List the causes of head trauma.

- Describe the presentation of head trauma

- Summarize the treatment of head trauma

- Recall the nursing management of a patient with head trauma

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a common presentation in emergency departments, which accounts for more than one million visits annually. It is a common cause of death and disability among children and adults.[1]

Based on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, it is classified as:

The leading causes of head trauma are (1) motor vehicle-related injuries, (2) falls, and (3) Assaults.[2][3]

Based on the mechanism, head trauma is classified as (1) blunt (most common mechanism), (2) penetrating (most fatal injuries), (3) blast.

Most severe TBIs result from motor vehicle collisions and falls.

Head trauma is more common in children, adults up to 24 years, and those older than 75 years.[4][5][6]

TBI is 3 times more common in males than females.

Although only 10% of TBI occurs in the elderly population, it accounts for up to 50% of TBI-related deaths.

A good history concerning the mechanism of injury is important. Follow trauma life support protocol and perform primary, secondary, and tertiary surveys. Once the patient is stabilized, a neurologic examination should be conducted. CT scan is the diagnostic modality of choice in the initial evaluation of patients with head trauma.

CT scan is required in patients with head trauma

For patients who are at low risk for intracranial injuries, there are two externally validated rules for when to obtain a head CT scan after TBI.[7][8]

It is important to understand that no individual history and physical examination finding can eliminate the possibility of intracranial injury in head trauma patients.

New Orleans Criteria

Canadian CT Head Rule

Level A Recommendation

With the loss of consciousness or posttraumatic amnesia only if one or more of the following symptoms are present:

Level B Recommendation

Without loss of consciousness or posttraumatic amnesia if one of the following specific symptoms presents:

The risk of intracranial injury when clinical decision rule results are negative is less than 1%.

For children, Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) decision rules exist to rule out the presence of clinically important traumatic brain injuries. However, this rule applies only to children with GCS > 14.

The most important goal is to prevent secondary brain injuries. This can be achieved by the following:

A relatively higher systemic blood pressure is needed:

Priorities remain the same: the ABC also applies to TBI. The purpose is to optimize perfusion and oxygenation.[1][9][10]

Airway and Breathing

Identify any condition which might compromise airway, such as pneumothorax.

For sedation, consider using short-acting agents having minimal effect on blood pressure or ICP:

Consider endotracheal intubation in the following situations:

The cervical spine should be maintained in-line during intubation.

Nasotracheal intubation should be avoided in patients with facial trauma or basilar skull fracture.

Targets:

Circulation

Avoid hypotension. A normal blood pressure may not be adequate to maintain adequate flow and CPP if ICP is elevated.

Target

Isolated head trauma usually does not cause hypotension. Look for another cause if the patient is in shock.

Increased ICP

Increased ICP can occur in head trauma patients resulting in the mass occupying lesion. Utilize a team approach to manage impending herniation.

Signs and symptoms:

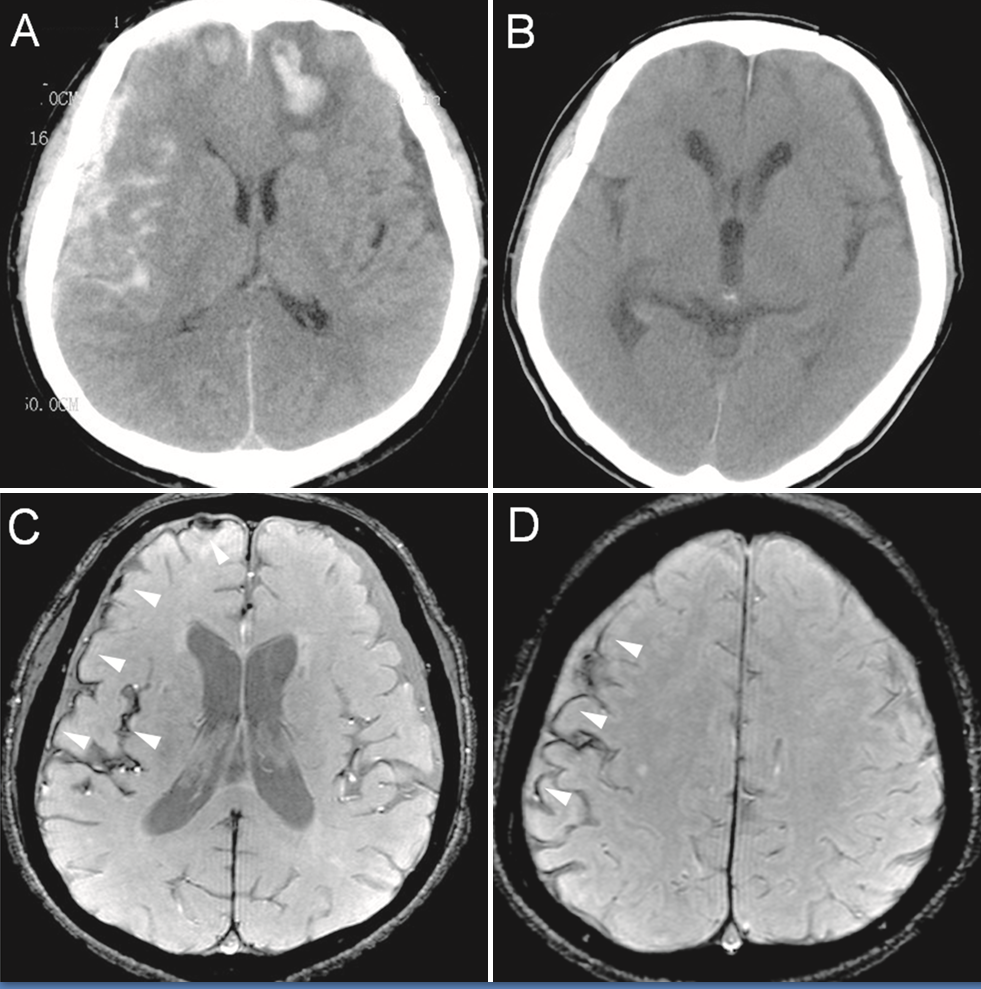

CT scan findings:

General Measures

Head Position: Raise the head of the bed and maintain the head in midline position at 30 degrees: potential to improve cerebral blood flow by improving cerebral venous drainage.

Lower cerebral blood volume (CBV) can lower ICP.

Temperature Control: Fever should be avoided as it increases cerebral metabolic demand and affects ICP.

Seizure prophylaxis: Seizures should be avoided as they can also worsen CNS injury by increasing the metabolic requirement and may potentially increase ICP. Consider administering fosphenytoin at a loading dose of 20mg/kg.

Only use an anticonvulsant when it is necessary, as it may inhibit brain recovery.

Fluid management: The goal is to achieve euvolemia. This will help to maintain adequate cerebral perfusion. Hypovolemia in head trauma patients is harmful. Isotonic fluid such as normal saline or Ringer Lactate should be used. Also, avoid hypotonic fluid.

Sedation: Consider sedation as agitation and muscular activity may increase ICP.

ICP monitoring:

Hyperventilation:

Normocarbia is desired in most head trauma patients. The goal is to maintain PaCO between 35-45 mmHg. Judicious hyperventilation helps to reduce PaCO2 and causes cerebral vasoconstriction. Beware that, if extreme, it may reduce CPP to the point that exacerbation of secondary brain injury may occur. Avoid hypercarbia: PaCO > 45 may cause vasodilatation and increases ICP.

Mannitol:

A potent osmotic diuretic with net intravascular volume loss

Reduces ICP and improves cerebral blood flow, CPP, and brain metabolism

Expands plasma volume and can improve oxygen-carrying capacity

Onset of action is within 30 minutes

Duration of action is from two to eight hours

Dose is 0.25-1 g/kg (maximum: 4 g/kg/day)

Avoid serum sodium > 145 m Eq/L

Relative contraindication: hypotension does not lower ICP in hypovolemic patients.

Hypertonic saline:

May be used in hypotensive patients or patients who are not adequately resuscitated.

Dose is 250 mL over 30 minutes.

Serum osmolality and serum sodium should be monitored.

Mild Head Trauma

The majority of head trauma is mild. These patients can be discharged following a normal neurological examination as there is minimal risk of developing an intracranial lesion.

Consider observing at least 4 to 6 hours if no imaging was obtained.

Consider hospitalization if these other risk factors are present:

Provide strict return precautions for patients discharged without imaging.

Head trauma is a major public health problem accounting for thousands of admissions each year and costing the healthcare system billions of dollars. The majority of patients with head trauma are seen in the emergency department and is often associated with other organ injuries as well. The care of a patient with head trauma is multidisciplinary as almost every organ system is affected. Most patients require admission and monitoring in an ICU setting. The outcome of these patients depends on the severity of the head trauma, initial GCS score, and any other organ injury. Data indicates that those patients with an initial GCS of 8 or less have a mortality rate of 30% within 2 weeks of the injury. Other negative prognostic factors include advanced age, elevated intracranial pressure, and presence of a gross neurologic deficit on presentation. Patients with a GCS less than 9 often require mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, and a feeding tube. With prolonged hospital stay, there are prone to pressure ulcers, aspiration, sepsis, failure to thrive and deep vein thrombus. Recovery in most patients can take months or even years. Even those who are discharged often have residual deficits in executive function or neurological deficits. Despite education of the public, many young people still lead a lifestyle that predisposes them to head injury. Young people still drink and drive, text while driving, abuse alcohol and illicit drugs, and are often involved in high-risk sporting activities, which makes them susceptible to head trauma.[11][12]

Educate on safety when playing sports

Wear helmet if working in jobs that are high risk for falls

Hyperglycemia may worsen the outcome.

An elevated temperature may increase ICP and worsen outcome.

A prolonged seizure may worsen secondary brain injuries.

Outcomes

Unfortunately, despite education of the public, many young people still lead a lifestyle that predisposes them to head injury. Young people still drink and drive, text while driving, abuse alcohol and illicit drugs, and are often involved in high-risk sporting activities, which makes them susceptible to head trauma.[11][12]

Head trauma is a major public health problem accounting for thousands of admissions each year and costing the healthcare system billions of dollars. The majority of patients with head trauma are seen in the emergency department; the head injury is often associated with other organ injuries as well. The care of a patient with head trauma is by an interprofessional team that is dedicated to managing head trauma patients.

Most patients require admission and monitoring in an ICU setting. The outcome of these patients depends on the severity of the head trauma, initial GCS score, and any other organ injury. Data indicate that those patients with an initial GCS of 8 or less have a mortality rate of 30% within 2 weeks of the injury. Other negative prognostic factors include advanced age, elevated intracranial pressure, and the presence of a gross neurologic deficit on presentation. ICU nurses play a vital role in the managing of these patients; from providing basic medical care, monitoring, DVT and ulcer prophylaxis and monitoring the patient for complications. The dietitian manages the nutrition and physical therapists provide bedside exercises to prevent muscle wasting.

Patients with a GCS less than 9 often require mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, and a feeding tube. With prolonged hospital stay, there are prone to pressure ulcers, aspiration, sepsis, failure to thrive and deep vein thrombus. Patients deemed to be brain dead are assessed by the entire team that includes specialists from end of life care.

Recovery in most patients can take months or even years. Even those who are discharged often have residual deficits in executive function or neurological deficits.Some require speech, occupational and physical therapy for months. In addition, the social worker should assess the home environment to make sure it is safe and offers amenities for the disabled person. Only through such a team approach can the morbidity of head trauma be lowered.

Brommeland T, Helseth E, Aarhus M, Moen KG, Dyrskog S, Bergholt B, Olivecrona Z, Jeppesen E. Best practice guidelines for blunt cerebrovascular injury (BCVI). Scandinavian journal of trauma, resuscitation and emergency medicine. 2018 Oct 29:26(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s13049-018-0559-1. Epub 2018 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 30373641]

Portaro S, Naro A, Cimino V, Maresca G, Corallo F, Morabito R, Calabrò RS. Risk factors of transient global amnesia: Three case reports. Medicine. 2018 Oct:97(41):e12723. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012723. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30313071]

Salehpour F, Bazzazi AM, Aghazadeh J, Hasanloei AV, Pasban K, Mirzaei F, Naseri Alavi SA. What do You Expect from Patients with Severe Head Trauma? Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2018 Jul-Sep:13(3):660-663. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_260_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30283522]

Mohammadifard M, Ghaemi K, Hanif H, Sharifzadeh G, Haghparast M. Marshall and Rotterdam Computed Tomography scores in predicting early deaths after brain trauma. European journal of translational myology. 2018 Jul 10:28(3):7542. doi: 10.4081/ejtm.2018.7542. Epub 2018 Jul 16 [PubMed PMID: 30344974]

Lalwani S, Hasan F, Khurana S, Mathur P. Epidemiological trends of fatal pediatric trauma: A single-center study. Medicine. 2018 Sep:97(39):e12280. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012280. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30278499]

Schneider ALC, Wang D, Ling G, Gottesman RF, Selvin E. Prevalence of Self-Reported Head Injury in the United States. The New England journal of medicine. 2018 Sep 20:379(12):1176-1178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1808550. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30231228]

Pavlović T, Milošević M, Trtica S, Budinčević H. Value of Head CT Scan in the Emergency Department in Patients with Vertigo without Focal Neurological Abnormalities. Open access Macedonian journal of medical sciences. 2018 Sep 25:6(9):1664-1667. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2018.340. Epub 2018 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 30337984]

Hajiaghamemar M, Lan IS, Christian CW, Coats B, Margulies SS. Infant skull fracture risk for low height falls. International journal of legal medicine. 2019 May:133(3):847-862. doi: 10.1007/s00414-018-1918-1. Epub 2018 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 30194647]

Jacquet C, Boetto S, Sevely A, Sol JC, Chaix Y, Cheuret E. Monitoring Criteria of Intracranial Lesions in Children Post Mild or Moderate Head Trauma. Neuropediatrics. 2018 Dec:49(6):385-391. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1668138. Epub 2018 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 30223286]

Bayley MT, Lamontagne ME, Kua A, Marshall S, Marier-Deschênes P, Allaire AS, Kagan C, Truchon C, Janzen S, Teasell R, Swaine B. Unique Features of the INESSS-ONF Rehabilitation Guidelines for Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Responding to Users' Needs. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation. 2018 Sep/Oct:33(5):296-305. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000428. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30188459]

Fitzpatrick S, Leach P. Neurosurgical aspects of abusive head trauma management in children: a review for the training neurosurgeon. British journal of neurosurgery. 2019 Feb:33(1):47-50. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2018.1529295. Epub 2018 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 30353746]

Hussain E. Traumatic Brain Injury in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Pediatric annals. 2018 Jul 1:47(7):e274-e279. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20180619-01. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30001441]