Continuing Education Activity

Thyroidectomy is a surgical procedure to remove all or part of the thyroid gland that is typically indicated for conditions such as thyroid cancer, hyperthyroidism, or large goiters. The surgery can be performed via various techniques, including open or minimally invasive approaches, with careful attention to preserving surrounding structures like the recurrent laryngeal nerves and parathyroid glands to minimize complications. While thyroidectomy generally has favorable outcomes, complications such as hypoparathyroidism, nerve injury, and postoperative bleeding highlight the importance of meticulous surgical technique and thorough preoperative assessment.

In this course, participants acquire an in-depth understanding of the latest thyroidectomy techniques, including enhanced anatomical recognition skills and nerve and parathyroid preservation strategies. Clinicians learn to minimize surgical risks by mastering advanced approaches and optimizing intraoperative decision-making. The course also emphasizes the value of interprofessional collaboration, highlighting how coordination with anesthesiologists, endocrinologists, and nursing staff supports comprehensive patient care and postoperative recovery. By integrating these competencies, clinicians are better prepared to improve surgical precision, reduce complication rates, and promote superior outcomes for patients undergoing thyroidectomy.

Objectives:

Apply knowledge of thyroid anatomy and surgical techniques to safely perform a thyroidectomy.

Assess patient indications for thyroidectomy, including malignancy, hyperthyroidism, and benign thyroid disease.

Differentiate between open and minimally invasive thyroidectomy techniques to select the best approach for each patient.

Coordinate with different care team members, creating a comprehensive preoperative and postoperative multidisciplinary care plan for patients undergoing thyroidectomy.

Introduction

Thyroidectomy is a surgical procedure involving the resection of the thyroid gland that can be classified into 2 main types: total thyroidectomy, which refers to the complete removal of the thyroid gland, and partial thyroidectomy, which includes procedures such as thyroid lobectomy. Thyroidectomy is indicated for a variety of conditions, including benign disorders such as multinodular goiter, toxic adenomas, and thyroiditis, as well as malignant conditions, including differentiated thyroid carcinoma and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma.[1]

Before undergoing thyroidectomy, patients must have their thyroid function evaluated to assess for hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism, which could influence perioperative management. Typically, a thyroid ultrasound serves as the initial imaging modality to evaluate the thyroid gland, allowing for the identification of structural abnormalities.[2] If suspicious nodules or lesions are detected, targeted fine-needle aspiration biopsies may be performed to determine these lesions' cytological characteristics and potential malignancy. The decision regarding whether to perform a thyroid lobectomy or total thyroidectomy is contingent upon various factors, including the size, location, and histopathological features of the thyroid pathology.

Surgical complications associated with thyroidectomy can include significant bleeding, which may necessitate reoperation, as well as recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, which can lead to vocal cord paralysis and resultant hoarseness.[3] Additionally, accidental injury to the parathyroid glands can result in postoperative hypoparathyroidism, characterized by hypocalcemia and its associated symptoms.[4] Postoperatively, it is essential to evaluate thyroid function, as many patients may require thyroid hormone replacement therapy to maintain euthyroid status following total thyroidectomy or substantial lobectomy. This comprehensive approach to managing thyroidectomy cases is critical for optimizing surgical outcomes and ensuring long-term health and well-being.

Anatomy and Physiology

Gross Anatomy

The thyroid gland is anatomically divided into 2 lateral lobes, interconnected by the isthmus, which crosses the midline of the upper trachea at the level of the second and third tracheal rings. In its anatomical position, the thyroid gland is posterior to the sternothyroid and sternohyoid muscles, encircling the cricoid cartilage and the tracheal rings, typically corresponding to vertebral levels C5 to T1. The gland attaches to the trachea via a consolidation of connective tissue known as the lateral suspensory ligament or ligament of Berry, which connects each thyroid lobe posteriorly to the trachea. The thyroid gland and the parathyroids, cervical esophagus, hypopharynx, larynx, and trachea reside within the neck's visceral compartment, bordered by the pretracheal fascia.

The normal thyroid gland has symmetrical lateral lobes and a well-defined centrally located isthmus. Additionally, 15% to 75% of individuals exhibit an embryologic remnant extending superiorly from the thyroid isthmus, referred to as the pyramidal lobe, which can vary in size from 3 mm to 6 cm.[5] The posterior aspect of each lobe may feature a pyramidal extension known as the tubercle of Zuckerkandl. Despite these general characteristics, the thyroid gland exhibits numerous morphologic variations. The gland typically weighs 15 to 25 grams in adults.

Vascular Supply and Drainage

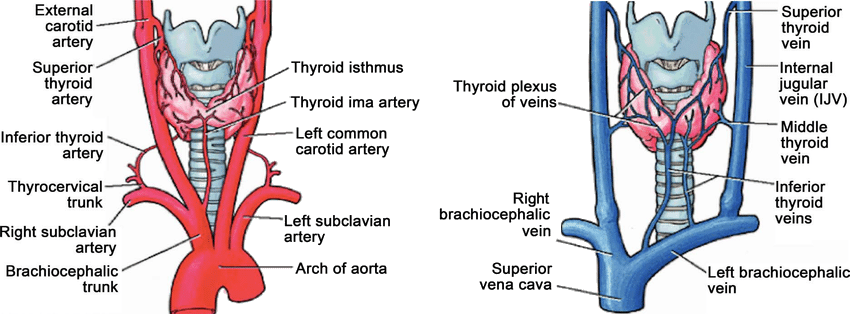

The thyroid gland possesses a rich vascular supply, primarily from the superior and inferior thyroid arteries. The superior thyroid artery, a branch of the external carotid artery, supplies the superior aspect of the gland. In contrast, the inferior thyroid artery, branching from the thyrocervical trunk, supplies the posterior surface of the lateral lobes. Additionally, the thyroid ima artery (thyroid artery of Neubauer) is present in about 3% to 10% of individuals, arising from the brachiocephalic trunk, aortic arch, or subclavian artery to supply the isthmus or lower thyroid lobes.[6]

The superior thyroid vein originates at the upper pole of the thyroid gland from the thyroid venous plexus. Traveling superiorly and laterally, it crosses over the superior belly of the omohyoid muscle and the common carotid artery before draining into the internal jugular vein. The superior thyroid artery accompanies this vein, which primarily drains venous blood from the thyroid gland and larynx, receiving tributaries from the superior laryngeal and cricothyroid veins. The middle thyroid vein is the shortest of the thyroid veins. This vein originates on the lateral surface of the thyroid lobe at the midthyroid level and then crosses the common carotid artery to empty directly into the internal jugular vein. The inferior thyroid vein arises from the lower border of the thyroid isthmus and typically appears as paired veins on the right and left. These veins descend to form the pretracheal venous plexus, which lies anterior to the trachea and deep into the sternothyroid muscle. The inferior thyroid veins are the largest and most variable among the thyroid veins, often showing asymmetry and differing patterns in number, course, and termination points.[7] See Image. Arterial and Venous Anatomy of the Thyroid Gland.

Lymphatics

The thyroid gland’s lymphatic drainage is extensive and multidirectional, flowing into several lymph node chains. The paratracheal and lower deep cervical nodes receive lymph from the inferior lateral lobes and the isthmus, while the paratracheal, laryngeal, submandibular, and submental nodes also receive drainage from the thyroid gland. This widespread lymphatic network is clinically significant, particularly in the context of thyroid malignancies, as it impacts the spread of cancer and the surgical approach for lymph node dissection.

Innervation

The superior and recurrent laryngeal nerves are vagus nerve branches. Due to their proximity to the gland, both play crucial roles in thyroid surgery.

Recurrent laryngeal nerve: This nerve loops under the aortic arch on the left and under the subclavian artery on the right, then ascends in the tracheoesophageal groove to innervate the intrinsic muscles of the larynx (except the cricothyroid muscle). Careful identification and preservation of this nerve during thyroidectomy is essential to prevent vocal cord paralysis.

Superior laryngeal nerve: This nerve bifurcates into external and internal branches. The external branch innervates the cricothyroid muscle, while the internal branch provides sensory innervation to the larynx above the vocal cords. Injury to this nerve can lead to voice fatigue and loss of high-pitched voice capability.

Sympathetic innervation: This innervation originates from the cervical sympathetic ganglia, specifically the superior, middle, and inferior ganglia. These nerves travel with blood vessels, particularly the superior and inferior thyroid arteries, to reach the thyroid. Sympathetic stimulation can influence the blood flow to the thyroid, potentially affecting hormone release in response to systemic needs. Additionally, sympathetic fibers also innervate the blood vessels within the gland, enabling vasoconstriction or vasodilation as required by the body.

Parasympathetic innervation: This innervation is derived from the vagus nerve (eg, cranial nerve X). Although the parasympathetic nervous system's role in regulating thyroid function is limited, the vagus nerve's branches, including the superior and recurrent laryngeal nerves, pass near the gland and are critical structures to protect during thyroid surgery. These nerves do not directly control thyroid hormone secretion but may influence local blood flow and contribute to some autonomic regulation of the gland’s vasculature.

Anatomic Surgical Considerations

The thyroid gland’s anatomical position and relationships with adjacent structures present unique surgical challenges. The gland's proximity to vital neurovascular and parathyroid structures necessitates careful dissection to ensure safe outcomes and minimize complications.

Recurrent laryngeal nerve: These nerves are particularly important to identify and preserve due to their critical role in vocal cord function. They travel within the tracheoesophageal groove before piercing the cricothyroid membrane to innervate the larynx. Anatomical variations, such as bifurcation or trifurcation near the laryngeal entrance, are present in some patients and require meticulous dissection to avoid inadvertent injury. A rare non-recurrent laryngeal nerve occurs in approximately 1% of patients undergoing thyroidectomy. Accurate identification, particularly near the tubercle of Zuckerkandl, is essential to minimize the risk of nerve injury, which could lead to voice changes or airway issues.

External branch of the superior laryngeal nerve: This branch traverses close to the superior thyroid artery, posing a risk of injury during the ligation of this vessel. Injury to this nerve can lead to a loss of pitch control due to impaired cricothyroid muscle function, a significant concern, especially for patients who rely heavily on vocal performance. Careful division of the superior pole vessels should be performed near the thyroid capsule to protect the superior laryngeal nerve.[8]

Parathyroid glands: Preserving the parathyroid glands and their blood supply is another crucial aspect of thyroid surgery. The superior parathyroid glands typically lie about 1 cm superior to the intersection of the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the inferior thyroid artery. In contrast, the inferior parathyroid glands have a more variable location, often residing somewhere along their embryologic descent path with the thymus. The superior glands are generally positioned dorsal to the plane of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, whereas the inferior glands are ventral. Blood supply to the parathyroids primarily stems from the inferior thyroid artery; in 20% to 45% of cases, the superior glands may receive additional supply from the superior thyroid artery or anastomosis with the inferior thyroid artery. Ectopic or supernumerary parathyroid glands, present in some patients, can be found in locations ranging from the lower mandible to the mediastinum, adding further complexity to their identification and preservation.[9]

Cervical sympathetic trunk, trachea, and esophagus: Rarely, the cervical sympathetic trunk, which lies posterior to the thyroid gland, may be at risk during extensive dissections. Injury to this structure can result in Horner syndrome. Additionally, due to the thyroid’s close proximity to the trachea and esophagus, these structures may be at risk of injury during procedures. Tracheal injury is a particular concern when dividing the ligament of Berry to release the thyroid, especially when using electrocautery. Although uncommon, esophageal injury may also occur, particularly in cases of large goiters or invasive tumors, necessitating prompt recognition and repair to prevent complications such as mediastinitis.

Clinical and Surgical Implications

Understanding both common and aberrant thyroid gland anatomy is essential for minimizing risks associated with thyroid surgery. Surgeons must be adept at identifying these structures, and preoperative imaging can aid in assessing anatomical variations, especially in cases with large goiters or malignancies. Meticulous dissection close to the thyroid capsule, nerve monitoring, and cautious handling of the parathyroid glands all contribute to reducing postoperative complications, preserving functional outcomes, and enhancing patient safety. This comprehensive anatomical knowledge supports effective, patient-centered surgical care.

Indications

Thyroidectomy may be performed for several benign and malignant conditions.[10] The indications for thyroidectomy include thyroid nodules and goiters, primary and metastatic thyroid malignancies, and hyperthyroidism.

Thyroid nodules: Nodules are the most common indication for thyroidectomy. Nodules are risk-stratified based on their sonographic appearance using the Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System system.[11] Higher-risk lesions warrant a thyroid biopsy, performed with a fine needle aspiration or core needle biopsy. Pathologic findings are graded using the Bethesda criteria. Bethesda 5 and 6 lesions (suspicious for malignancy and malignant, respectively) undergo surgery. Bethesda 3 and 4 lesions (atypia of undetermined significance or follicular neoplasm) may undergo surgery, with molecular markers helping to further risk stratify these lesions.

Symptomatic goiter: Surgery is indicated for enlarged thyroid glands that cause symptoms such as dysphagia, dyspnea, chronic cough, obstructive sensation, or significant compression of surrounding structures.

Primary thyroid malignancy: Papillary thyroid cancers larger than 1 cm or with high-risk features should undergo surgery. Follicular thyroid cancers should undergo surgery. However, the diagnosis of follicular carcinoma can often only be made after a thyroid lobectomy. Differentiating between a benign follicular adenoma and a follicular thyroid carcinoma requires pathologic evidence of capsular or vascular invasion, which is only possible on a thyroid lobectomy specimen. All patients with undifferentiated tumors, oncocytic, medullary, and anaplastic thyroid cancers, require a total thyroidectomy at the minimum. More extensive resection and lymph node dissections may be indicated in certain situations.

Hyperthyroidism: Medically uncontrolled hyperthyroidism due to autoimmune thyroiditis, toxic multinodular goiter, or toxic adenomas can be corrected with total thyroidectomy.

Other malignancies: Thyroid lymphoma, melanoma, and metastatic disease to the thyroid gland are rare indications for thyroidectomy.

Type of Thyroid Resection

The specific circumstances dictate the decision to perform a total or partial thyroidectomy. Generally, diagnostic procedures (like repeat atypia of uncertain significance or Bethesda 4 lesions) and low-risk tumors (such as small papillary thyroid cancers without high-risk features) can be effectively treated with a thyroid lobectomy. More aggressive tumors, bilateral disease, hyperthyroidism, or goiter may require a total thyroidectomy. Based on the initial thyroid lobectomy specimen analysis, patients who undergo a thyroid lobectomy might need a completion thyroidectomy.

Contraindications

Contraindications to thyroidectomy are limited, as the procedure is often necessary for managing thyroid cancer. Regardless of the underlying condition, careful patient selection is essential. Absolute contraindications are rare but may involve patients with severe, uncorrected coagulopathies or unstable medical conditions such as uncontrolled heart failure or severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, where general anesthesia poses significant risk. For patients with thyroid malignancy, the slow progression of most thyroid cancers allows for an individualized risk-benefit analysis, especially in older adults where comorbidities may affect treatment decisions.

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma presents a unique challenge due to its rapid progression and generally poor prognosis.[12] Surgery may be considered if gross total resection is feasible with minimal morbidity and no metastases, but it is often contraindicated due to the high surgical risk and limited benefit.[13] While not absolute contraindications, certain factors can make outpatient or conventional thyroidectomy more complex. These relative contraindications include massive or extensive substernal goiters, locally advanced carcinoma, challenging hemostasis, and patients with autoimmune thyroiditis like Hashimoto or Graves disease, which can increase tissue friability and vascularity.[14] Careful preoperative planning and patient counseling are essential to assess whether the benefits of surgery outweigh the potential risks, especially in challenging cases where alternatives to surgery may be considered.

Equipment

Thyroidectomy procedures require a standard head and neck surgery instrument set and essential high-quality lighting for optimal visibility. Additional specialized equipment varies depending on the surgical setting and availability but can enhance outcomes. For instance, energy devices like harmonic scalpels or bipolar diathermy devices are beneficial, as they help control blood loss, expedite the procedure, and support faster postoperative discharge.[15] Intraoperative recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring is also increasingly common. This technology provides real-time feedback through nerve stimulation, assisting the surgeon in identifying and preserving the nerve, which is crucial for reducing the risk of postoperative vocal cord dysfunction.

Personnel

The personnel required to perform a thyroidectomy typically include:

- Primary surgeon

- Surgical assistant (not an absolute requirement)

- Surgical technician or operating room nurse

- Circulating or operating room nurse

- Anesthesia personnel

Preparation

Preoperative Therapy

Preoperative management for thyroidectomy emphasizes ensuring that patients are in a euthyroid state to reduce perioperative complications. For hyperthyroid, antithyroid medications like methimazole or propylthiouracil are typically prescribed to stabilize thyroid hormone levels, along with nonselective beta-blockers, such as propranolol, to control symptoms and heart rate. This approach is crucial as hyperthyroid patients are at high risk for severe thyrotoxicosis or thyroid storm during or after surgery, necessitating close monitoring.

To further prepare the thyroid, some surgeons administer iodine solutions, such as Lugol solution or potassium iodide, which inhibit thyroid hormone synthesis and secretion via the Wolff-Chaikoff effect. This practice can reduce gland vascularity and may help lower intraoperative blood loss. Although the evidence supporting these practices is limited, some surgeons elect to administer oral iodine before surgery as a precautionary measure against thyroid storm and excessive bleeding.[16] Additionally, administering calcium and calcitriol preoperatively may reduce the incidence of postoperative hypoparathyroidism, a frequent complication following thyroidectomy. Preliminary data suggest this protocol could improve calcium stability postoperatively, enhancing patient outcomes.

Laryngeal Examination

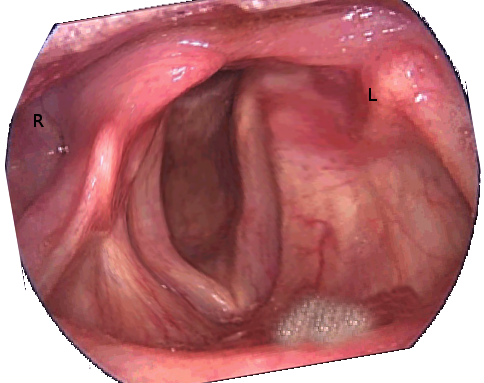

Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury during thyroidectomy poses a risk of vocal cord paresis or paralysis, which can severely impact a patient’s quality of life. Therefore, a thorough preoperative voice assessment is recommended to identify any existing vocal abnormalities. If abnormalities are present, flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy should be considered to evaluate the laryngeal structures’ function and integrity.[17] This proactive assessment informs surgical planning and helps tailor risk mitigation strategies, contributing to optimized laryngeal function preservation and overall surgical outcomes.

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine with the neck hyperextended, typically aided by a shoulder roll to enhance surgical exposure, and the head is placed on a donut cushion to prevent strain. In older patients with limited neck mobility, excessive extension should be avoided. Elevating the head or using a beach chair position can improve venous drainage and reduce venous engorgement. Key anatomical landmarks, including the sternal notch, thyroid and cricoid cartilages, and midline, are identified and marked. The midline is established using the sternal notch and mandible for reference, ensuring precise orientation. The thyroid and cricoid cartilage landmarks are also marked to assist the surgical team.

If intraoperative monitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve is planned, general anesthesia is induced, and the patient is intubated with a nerve-monitoring endotracheal tube (ETT). Correct ETT positioning places the monitoring sensors between the vocal cords, and functionality is verified per the manufacturer’s instructions. Connected to the monitor, the ETT provides real-time electromyography feedback from the vocalis muscles, allowing continuous recurrent laryngeal nerve assessment. The monitor alerts the team to nerve output or stimulation changes, significantly aiding in nerve preservation. Study results show that 83% to 85% of patients who lose signal during surgery develop postoperative vocal cord paresis or paralysis.[18][19] Furthermore, recent meta-analyses suggest that intraoperative nerve monitoring is associated with a reduced incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, underscoring intraoperative monitoring's value in reducing risk.[20] The surgical site is then prepped and draped aseptically, completing the setup for thyroidectomy.

Technique or Treatment

This section outlines the steps involved in performing a total thyroidectomy. While there is no single correct sequence, and techniques may vary, these steps provide a general framework for the procedure. To optimize outcomes, surgeons may adapt the order and approach based on specific patient anatomy, pathology, and intraoperative considerations. The steps are:

Incision: A transverse skin crease incision is typically made approximately 2 cm above the sternal notch, adjusted based on the thyroid gland’s size and the extent of the planned operation; using a natural skin crease aids in minimizing scarring. Local anesthetic with epinephrine is often injected before the incision to reduce bleeding in the skin and platysma. The incision is made through the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and platysma. Notably, the platysma may be thinner or absent in the midline, becoming more visible as the dissection moves laterally. All bleeding is meticulously controlled at each layer to maintain a clear field.

Raising subplatysmal flaps: Subplatysmal flaps are carefully elevated superiorly and inferiorly, with the platysma retracted superiorly to enhance exposure. A combination of blunt and sharp dissection, aided by electrocautery, allows for the extension of the subplatysmal plane from the thyroid cartilage to the sternal notch. Achieving an adequate plane here is critical, especially when using a minimally invasive incision, as it directly impacts surgical exposure. Preserving the anterior jugular veins is essential; these veins should stay posterior to the dissection plane to avoid unintended injury. Ligation can effectively control bleeding if the anterior jugular vein is inadvertently damaged.

Thyroid gland exposure: The strap muscles, specifically the sternohyoid and sternothyroid, are mobilized laterally by incising the median raphe to expose the thyroid capsule. Direct dissection down to the thyroid capsule is essential to avoid leaving any fascial layers over it. The midline raphe is generally avascular, although small bridging veins, which connect the anterior jugular veins on either side, may occasionally be encountered. For a total thyroidectomy, it is typically recommended to begin dissection on the side with confirmed malignancy or, if benign, on the larger side. This strategy prioritizes addressing the most critical aspect of the thyroid before concluding the surgery if complications arise, such as an intraoperative nerve injury that might necessitate early termination.

Blunt dissection then progresses through the loose areolar tissue covering the thyroid gland, extending laterally until the carotid sheath is reached, which defines the lateral boundary of the dissection. This step can be performed with careful finger dissection or with bipolar cautery retraction. The middle thyroid vein may appear at this stage and should be ligated. In cases where a large goiter obstructs access, division of the strap muscles may be required to improve exposure. If division is necessary, it should be performed as superiorly as possible to maintain innervation by the ansa cervicalis and preserve muscle function.

Superior pole dissection: The thyroid lobe is gently retracted anteromedially to expose the superior thyroid artery and vein. The avascular plane between the superior pole vessels laterally and the cricothyroid muscle medially is carefully developed using blunt dissection, working from an inferior to superior direction. This process creates a dissection window just below the superior thyroid vessels. Keeping dissection close to the thyroid capsule helps reduce the risk of damaging the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. The superior thyroid vessels are then secured with ligatures, surgical clips, or energy devices, and the surrounding loose areolar tissue is divided once these vessels are ligated. Precision during this step is essential to avoid injuring the superior parathyroid glands. By ligating the superior pole vessels, the thyroid lobe can be elevated and rotated medially, which aids in exposing the tracheoesophageal groove and the area of the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Recurrent laryngeal nerve identification: Identification of the nerve typically follows exposure of the superior pole vessels. The recurrent laryngeal nerve generally courses from an inferolateral to superomedial direction along the prevertebral fascia before penetrating the cricothyroid membrane to innervate the laryngeal muscles. Key anatomical landmarks assist in locating the nerve, including its usual position posterior to the tubercle of Zuckerkandl, anterior to the inferior parathyroid glands, and posterior to the superior parathyroid glands. The nerve often lies near the branches of the inferior thyroid artery, making early ligation of this artery a potential risk factor for nerve injury.[21][22][23]

If locating the nerve along its tracheoesophageal groove path proves difficult, visualization at its cricothyroid membrane entry may help. Optimal visualization requires proper soft tissue retraction, typically achieved with an Army-Navy or similar retractor, alongside medial rotation and elevation of the thyroid lobe. Dissection progresses carefully through the delicate areolar tissue until the nerve is clearly identified. Following the nerve’s surface to its entry at the cricothyroid membrane minimizes the risk of division. Excessive nerve traction and thermal energy application should be avoided. When using a nerve stimulator, stimulating the nerve and confirming appropriate responses can aid identification and preservation. Keeping the nerve in direct view as the thyroid tissue is separated throughout dissection ensures nerve safety and minimizes the chance of injury.

Parathyroid gland identification: Identifying and preserving the parathyroid glands is essential in thyroidectomy to prevent hypoparathyroidism and maintain calcium homeostasis. While often described as a distinct step, parathyroid identification occurs progressively during the procedure. The superior parathyroid glands generally have a consistent location on the posterior aspect of the upper thyroid lobe, approximately 1 cm above the intersection of the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the inferior thyroid artery. The recurrent laryngeal nerve typically runs anterior to the superior parathyroid glands. Conversely, the inferior parathyroid glands display greater anatomical variability, often near the inferior thyroid artery and typically positioned anteriorly to the recurrent laryngeal nerve.[24] Care must be taken during dissection to preserve the delicate vascular supply of the parathyroid glands, which is crucial for maintaining their function. In cases where a parathyroid gland is inadvertently excised or becomes ischemic, autotransplantation can be performed by implanting the gland into the sternocleidomastoid or brachialis muscle belly, offering the potential for functional restoration.

Inferior pole dissection: During the dissection of the thyroid’s inferior pole, the branches of the inferior thyroid artery and vein must be ligated individually due to their typical branching pattern before entering the gland. Identifying the recurrent laryngeal nerve before addressing the inferior pole vessels is strongly recommended to improve surgical safety, as this nerve often lies near these vessels. This careful approach minimizes the risk of accidental nerve injury during vessel ligation, allowing for safer dissection and protecting the patient’s vocal function.

Specimen removal: Once the inferior pole has been dissected, the thyroid lobe is primarily attached only at the tubercle of Zuckerkandl and the ligament of Berry. These structures are relatively avascular, allowing for separation using sharp dissection or an energy device. During this step, special care must be taken to avoid injury to the underlying trachea. In the case of a total thyroidectomy, the same procedure is then repeated on the opposite side. If intraoperative nerve monitoring is used, verifying the integrity of the recurrent laryngeal nerve and preserving the parathyroid glands is essential before continuing.

Closure: Before closure, meticulous hemostasis is essential, and topical hemostatic agents, such as fibrin sealants, can be beneficial in reducing postoperative bleeding and seroma formation.[25] While closed suction drainage is not routinely employed, it may be indicated for patients with large goiters or those at higher risk for fluid accumulation. The strap muscles are loosely reapproximated with sutures, and the platysma is closed using absorbable sutures to prevent the incision from adhering to the trachea, which minimizes the risk of scar contracture. The skin is then closed with subcuticular sutures, followed by applying a suitable dressing. Typically, deep extubation is preferred, as it reduces the likelihood of coughing or excessive straining that could exacerbate venous bleeding during the immediate postoperative period.

Postoperative Care

Most patients undergoing thyroidectomy can be discharged home on the same day, although certain patient-specific or procedural factors may necessitate hospital admission. Patients must be assessed for symptoms of hypocalcemia, including checking their ionized calcium and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels. Symptomatic hypocalcemia typically requires oral calcium supplementation, while more severe cases may necessitate intravenous calcium and close inpatient monitoring. Patients who have undergone total thyroidectomy are generally discharged with oral calcium supplements, and calcitriol supplementation may be indicated for those presenting with symptomatic hypocalcemia and low PTH levels.[26]

All patients who undergo a total thyroidectomy will require lifelong synthetic thyroid hormone replacement. The initial dosage is usually calculated at 1 to 2 mcg/kg/day, adjusted to maintain thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels within the target range. Older patients or those at higher risk for atrial fibrillation may be initiated on a lower dose.[27] Historically, patients requiring postoperative radioactive iodine therapy were temporarily deprived of thyroid hormone to elevate TSH levels and enhance iodine uptake sensitivity. However, many centers now utilize recombinant TSH, which allows for TSH stimulation without requiring thyroid hormone withdrawal, a protocol that patients generally tolerate better.[28]

Complications

Thyroidectomy is generally a safe procedure. Notable complications include:

- Hemorrhage: The thyroid bed is highly vascular, making postoperative bleeding an infrequent but potentially life-threatening complication that can cause airway compromise. Patients with vascular or enlarged thyroid glands are at increased risk. Most postoperative bleeding originates from venous sources and can rapidly lead to hematoma formation, necessitating urgent evacuation under general anesthesia to ensure complete hemostasis. In extreme cases of severe bleeding that compromises the airway, the wound may need to be reopened immediately at the bedside, with the potential for an emergency tracheostomy to secure the airway.[29][30]

- Hypoparathyroidism: Up to one-third of patients undergoing total thyroidectomy may experience transient hypocalcemia due to temporary ischemia or “stunning” of the parathyroid glands. A calcium management protocol is critical postoperatively to mitigate hypocalcemia complications. While most cases resolve within a few weeks, about 1% to 2% of patients may develop permanent hypoparathyroidism, necessitating lifelong calcium and calcitriol supplementation. Severe symptomatic hypocalcemia can require intravenous calcium therapy.[31][32]

- Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury: Intraoperative neuromonitoring aids in nerve identification and preservation, reducing the likelihood of damage. Injury to the nerve may present immediately or be delayed, with symptoms like hoarseness, aspiration during swallowing, and a weakened cough reflex. Although most injuries are temporary due to stretching or contusion, persistent symptoms may necessitate laryngoscopy to evaluate vocal cord function. Permanent injuries may require interventions such as vocal cord medialization to improve phonation.[33][34]

- Superior laryngeal nerve injury: Dissection near the superior pole of the thyroid gland can potentially injure the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, which innervates the cricothyroid muscle. These injuries may often go unrecognized, as they can present with subtle changes in voice pitch that patients and healthcare providers may overlook. As a result, reported rates of injury vary significantly, ranging from 0% to 58%.

- Postoperative infection: Postoperative infection occurs in approximately 6% of thyroidectomy cases, though rates may vary depending on patient risk factors and procedural factors.

- Esophageal injury: Although rare, esophageal injury can occur during thyroid surgery, often necessitating prompt recognition and repair to prevent mediastinitis or other complications.

- Tracheal injury: Although an injury to the trachea is an uncommon complication of thyroid surgery, it can lead to airway challenges and may require immediate repair.

- Horner syndrome: This rare complication is caused by damage to the sympathetic chain and presents with ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis. This complication can occur if there is excessive dissection or traction near the cervical sympathetic trunk.

- Dysphagia: Patients may experience difficulty swallowing postoperatively due to temporary edema, scarring, or nerve irritation, which are generally temporary. However, persistent swallowing difficulties may require further evaluation.

- Chyle leak: A chyle leak is a rare complication that can occur when the thoracic duct or its branches are injured, particularly during extensive dissection in the lower neck. Management varies depending on the severity of the leak, from dietary modifications to surgical repair in more severe cases.

Careful surgical techniques and appropriate intraoperative monitoring help reduce the incidence and severity of these complications. Additionally, close postoperative monitoring, especially in the first 24 hours, is essential for the timely identification and management of any complications.

Clinical Significance

Thyroidectomy, the surgical removal of all or part of the thyroid gland, holds substantial clinical significance due to its role in managing various thyroid-related diseases and its potential impact on the patient’s endocrine function and quality of life. Indications for thyroidectomy typically include thyroid malignancies, symptomatic goiters, and hyperthyroidism refractory to medical management. In the context of thyroid cancer, total or near-total thyroidectomy is often the primary treatment for well-differentiated carcinomas such as papillary and follicular thyroid cancer.

Removing the gland allows for complete pathological examination, aids in staging, and sometimes improves survival rates. Following surgery, patients are usually monitored with serum thyroglobulin as a tumor marker, and radioiodine ablation may be considered to eliminate residual tissue, enhancing long-term prognosis. For aggressive cancers like anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, thyroidectomy can be controversial due to rapid tumor progression and high morbidity. However, it may be pursued in cases where gross total resection is achievable and can significantly improve outcomes.

For patients with large or symptomatic goiters, particularly when goiters extend substernal and compress the trachea or esophagus, thyroidectomy can relieve obstructive symptoms and improve quality of life. This is especially relevant when the enlarged thyroid causes difficulty breathing, swallowing, or even visible neck deformity. In such cases, surgery often provides immediate symptom relief and addresses any potential for further progression of gland enlargement.

Hyperthyroidism is another important indication, particularly in cases where antithyroid drugs are ineffective, contraindicated, or lead to severe side effects. Patients with Graves disease, toxic multinodular goiter, or a toxic adenoma may undergo thyroidectomy, achieving a definitive resolution of hyperthyroidism. Unlike RAI therapy, thyroidectomy is an immediate solution, which can be critical for patients with severe thyrotoxicosis or those planning pregnancy.

The removal of the thyroid gland has significant postoperative implications. In total thyroidectomy, patients require lifelong thyroid hormone replacement to compensate for the loss of thyroid function. Levothyroxine doses are typically adjusted to maintain TSH levels within target ranges, with higher doses sometimes needed in patients with cancer to suppress TSH. Adjusting these doses can be challenging, especially in older patients or those with cardiovascular comorbidities, due to the risks of both hypothyroidism (leading to fatigue, weight gain, and depression) and hyperthyroidism (increasing the risk of atrial fibrillation and osteoporosis).

Another critical aspect of thyroidectomy is the risk of surgical complications. Injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, parathyroid glands, and surrounding vascular structures can lead to significant morbidity, including vocal changes, hypocalcemia, and, in rare cases, life-threatening hemorrhage. Although these risks are low with experienced surgeons and appropriate precautions, they are relevant considerations that necessitate thorough preoperative planning and informed consent. Thyroidectomy also has unique implications in the follow-up care of patients with thyroid cancer. For instance, after total thyroidectomy and radioiodine therapy, clinicians monitor serum thyroglobulin levels as a tumor marker. Elevated thyroglobulin can indicate recurrence, prompting further imaging or intervention. Additionally, recombinant TSH can now be used in place of thyroid hormone withdrawal to elevate TSH levels before RAI therapy, improving patient comfort and compliance.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Caring for patients undergoing thyroidectomy is a highly collaborative effort requiring technical skill, strategic planning, and a commitment to patient-centered care from a multidisciplinary team. Clinicians, particularly surgeons, must demonstrate precise surgical skills and strategic decision-making to preserve critical structures and reduce risks. Surgeons, anesthesiologists, and advanced clinicians work together to evaluate surgical risks and create tailored preoperative and postoperative plans, ensuring optimal outcomes and patient safety. Advanced clinicians also support informed consent by explaining procedure risks, benefits, and alternatives and addressing concerns about quality-of-life impacts such as voice changes. Nurses play a key role in patient education, providing continuous monitoring, and managing potential complications like hypocalcemia and airway compromise.

Pharmacists contribute by managing calcium and thyroid hormone supplementation, ensuring accurate dosing, and minimizing drug interactions, which is especially important for patients requiring lifelong therapy post-thyroidectomy. Interprofessional communication is fundamental for the timely identification and management of complications, and regular team meetings improve care coordination, reduce errors, and support continuity of care. Through clear communication and standardized care pathways, the team monitors vocal cord function, coordinates follow-up care, and fosters a culture of safety. By valuing each professional’s expertise, this collaborative approach ensures high-quality, patient-centered care, enhancing surgical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and overall team performance throughout the perioperative period.