Definition/Introduction

Nuclear medicine uses radioactive materials and their emitted radiation from the body to diagnose and treat disease. Unstable atoms (radionuclides) are typically administered orally or intravenously and, less commonly, intra-arterially, directly into the CSF spaces, peritoneum, or joint space. These radionuclides are often chelated (labeled or tagged) with other molecules that provide them their physiologic properties, forming a radiopharmaceutical and allowing the combination to preferentially localize to organs of interest. Specialized cameras are used to record the radiation emission from these unstable atoms to localize pathology and guide treatment.

In the field of medicine, nuclear physics helps us understand:

- Which atoms and their tagged molecules can be used in diagnostics.

- Which radioactive atoms can be used in therapeutics

- Precautions necessary to protect the general public from radiation

- Precautions necessary to minimize the patient radiation

- The type of shielding and other protective measures necessary in the handling of certain radioactive products

- The proper disposal of radioactive substances in the nuclear medicine department

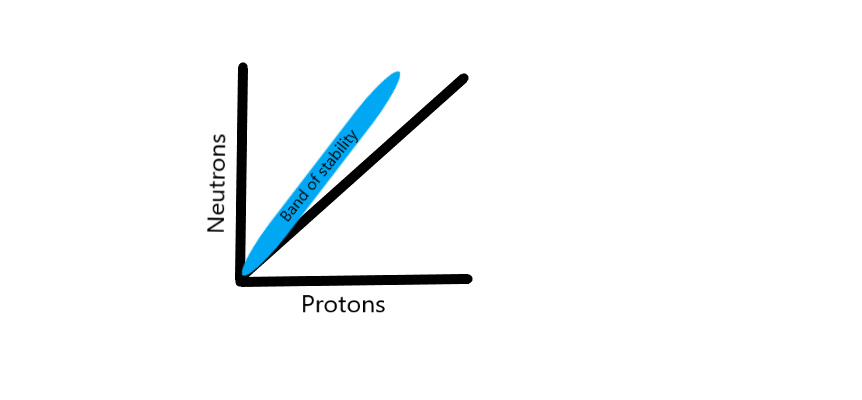

The nucleus of an atom consists of protons and neutrons held together by a strong nuclear force. Atoms are stable when this strong nuclear force can keep its constituent protons and neutrons within the nucleus. When the number of neutrons and protons are plotted on a graph, stable nuclei have been found to fall within a narrow region called the “band of stability” that closely approximates a 1:1 ratio of neutrons to protons in low atomic number atoms (see Graph. Band of Stability). As the atomic weight of an atom increases, this ratio skews towards a higher ratio of neutrons when compared to protons. This band of stability helps us understand the basis of nuclear physics, as atoms that are located outside of this band undergo reactions (decay) in an attempt to “reach” this band of stability.

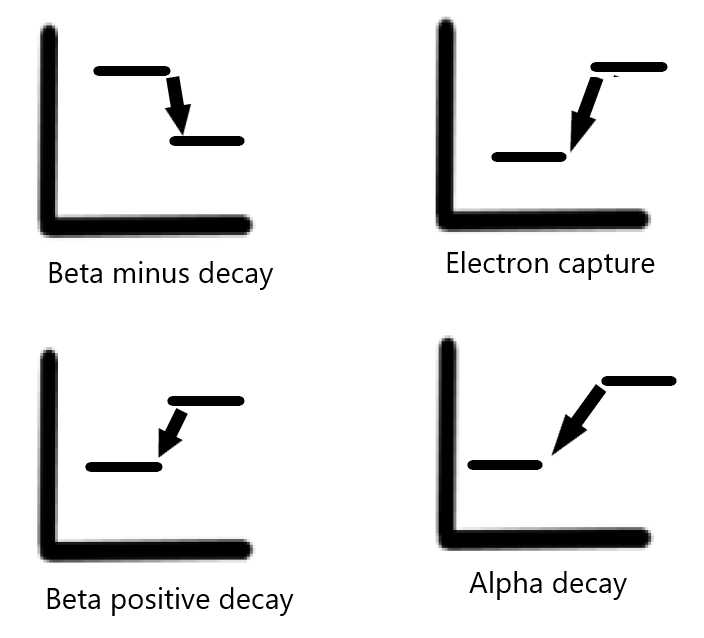

Types of decay – Depending on the imbalance between protons and neutrons, different types of nuclear decay occur (see Graph. Types of Decay When Plotted on a Graph).[1][2] These include:

Beta positive decay – occurring with an excess of protons.

Electron capture – occurring with an excess of protons.

Beta minus decay – occurring with an excess of neutrons.

Alpha decay – occurring with atoms with high atomic weights that are unstable.

Beta positive decay – Beta positive decay occurs when an atom has an excess of protons (and a low number of neutrons). In this process, a positively charged proton is converted into a neutron, which is neutral in charge. This process results in the emission of a positron and a neutrino (a particle without charge and whose mass is essentially zero). A positron is akin to a positively charged version of an electron. Depending on its energy, this positron traverses a short distance until its energy decreases to 1.02 MeV and it encounters an electron, resulting in an annihilation event. The result of an annihilation event is the emission of two photons emitted 180 degrees opposite in direction from each other, each measuring 511 keV in energy. This emission of two photons is the basis of PET imaging.

Electron capture – Electron capture results from the “capture” of a negatively charged electron by a proton heavy nucleus resulting in a neutron. This electron is usually located in the K shell of an atom. The process of electron capture is an isobaric transition, considering the atomic mass (total number of protons and neutrons) does not change. The atomic number, based upon the number of protons in the nucleus, decreases since a proton is now transformed into a neutron. The electron capture process is also an isomeric transition, resulting in the emission of photons that can be used for imaging.

Beta minus decay – Beta minus decay occurs when an atom contains an excess of neutrons.[1] In this process, a neutron is transformed into a proton, resulting in a beta particle release and an anti-neutrino. A beta particle is akin to an electron. However, it is distinguished from an electron due to its origin from the nucleus. The release of an anti-neutrino and a beta particle balances the change of charge in the process. The atomic number also increases by one, considering the neutron is now transformed into a proton. This process is an isobaric transition, as the mass of the atom has not changed. Beta minus imaging is not useful for imaging but is useful in therapy.

Alpha decay – Alpha decay occurs when the nucleus emits an alpha particle. An alpha particle is essentially a helium-4 atom and consists of two protons and two neutrons. Alpha particles have a charge of +2 and are emitted by heavy nuclides.

Isomeric transition – After the isobaric transition, excess energy is emitted in the form of isomeric transition, mostly by emitting gamma photons. These gamma photons' energy is variable and depends on the intermediate and final states of the nucleus undergoing isomeric transition. These packets of released energy in the form of gamma photons often provide a unique fingerprint for different radionuclides, as each releases a predictable amount of energy to reach its stable state. The intermediate states can be short in duration, or as in the case of “metastable states” can belong, as is the case with technetium 99-metastable radionuclides used in imaging. Technetium 99-metastable radionuclides release 140 keV photons before reaching their stable ground state.

Production of radionuclides – Atoms with an excess of neutrons and protons can be generated for medical imaging and therapy. Radioactive material not occurring naturally is generated by bombardment and fission, which results in unstable isotopes (a nucleus with an “unfavorable” neutron: proton ratio). The bombardment occurs via the irradiation of a nucleus with either neutrons (in a nuclear reactor) or other charged particles from a cyclotron. Charged particles in a cyclotron used to irradiate neutrons can include alpha particles, deuterons, or protons. The daughter isotopes resulting from bombardment are separated easily in cyclotrons where transmutation occurs (a change in atomic number) and less easily in processes involving neutron bombardment (when atomic numbers are not changed). Neutron bombardment and nuclear fission generally result in nuclei with a neutron excess, and cyclotron-produced isotopes are neutron deficient.

Half-life – The physical half-life of a radionuclide denotes the amount of time it takes for its activity to be reduced to half of its existing activity. The biological half-life of a radionuclide denotes the amount of time it takes for the radionuclide to reduce to half of its concentration within the human body (often through excretion or exhalation). The effective half-life describes the combination of these two aspects of a radionuclide.