Organ Systems Involved

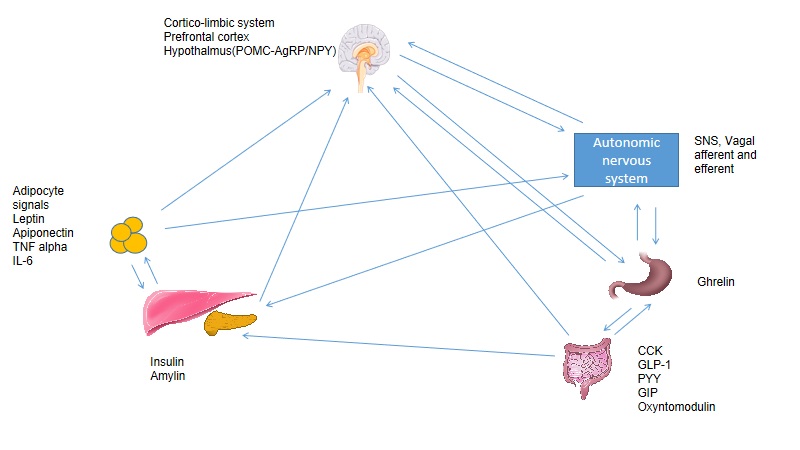

The nervous and endocrine systems are the most important regulators of body weight. Their actions influence food-seeking behavior, physical activity, digestion, and nutrient metabolism. Current research shows that the structures below are involved (see Image. Central and Peripheral Control of Weight and Appetite).

Cortico-Limbic System

The cortico-limbic system houses the reward centers. This region is an important target in the pharmacologic treatment of obesity.[5] The structures below are part of the cortico-limbic system.

Frontal and Prefrontal Cortex

The frontal and prefrontal cortical regions regulate eating control and food choices. These areas modulate food-seeking behavior aided by the sensory, limbic, and autonomic nervous systems.

Evidence also links the right prefrontal cortex with spontaneous physical activity. Conversely, physical activity can increase the size of this area. The right prefrontal cortex is vital in long-term decision-making and judgment. Injuries in this region may explain poor food choices and non-adherence to weight control interventions. Stress signals from this region also activate the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, causing hypersecretion of cortisol that contributes to obesity. Rodent studies implicate the prefrontal cortex as the site of leptin's effect on appetite.

Frontal and prefrontal injuries cause appetite disturbances. Related conditions include the following:

- Overactivity of the right frontal lobe in right frontal lobe epilepsy leads to anorexia, which resolves after therapy with antiepileptics.[6]

- Gourmand syndrome results from right frontal cortical damage. Patients develop a passion for eating gourmet foods and talking about fine foods.

- Right frontal atrophy is linked to hyperphagia and weight gain. Meanwhile, left frontal atrophy is associated with weight loss.[7]

- Klein-Levin syndrome is a rare condition manifesting with excessive sleepiness, compulsive overeating, and behavioral disturbance. This syndrome is associated with hypoperfusion of the right frontal lobe.[8]

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus is critical to appetite and energy expenditure. This region coordinates with cortical, limbic, and autonomic centers and receives inputs from the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, liver, adipocytes, leptin, and vagal branches.[9]

The arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus is located adjacent to the median eminence and 3rd ventricle. The area is highly vascularized. Thus, the arcuate nucleus is exposed to hormones passing through the blood-brain barrier.

Two antagonistic systems in the arcuate nucleus regulate appetite and maintain long-term and short-term energy balance. The first produces the prohormone pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC), which suppresses appetite. The second secretes neuropeptide Y (NPY) and Agouti-related protein (AgRP), which stimulate appetite.[10]

POMC produces adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in the pituitary gland and is likewise metabolized into alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH) and β-endorphins. Activation of the melanocortin 3 (MC3R) and melanocortin 4 (MC4R) receptors in the brain by POMC or α-MSH leads to satiety.

The NPY-AgRP neurons antagonize the POMC pathway and are activated by starvation. MC3R is expressed in NPY/AgRP neurons, acting as an inhibitory autoreceptor for the POMC pathway.

POMC gene mutation produces obesity, ACTH insufficiency, and hair depigmentation. MC4R mutations present with obesity, increased linear growth, hyperphagia, and hyperinsulinemia. An MC4R agonist, setmelanotide, is under development for POMC deficiency.

Cocaine and Amphetamine-regulated Transcript (CART)

CART is a neuropeptide that suppresses appetite. The hypothalamus secretes this molecule in response to nutrient absorption information carried by gut vagal afferents. CART interacts with leptin, ghrelin, and the POMC pathway.[11]

Serotonin

Central 5HT-receptor activation suppresses appetite. Stimulation of 5HT2C receptors induces the POMC neuronal pathway, whereas 5HT1B activation inhibits the NPY/AgRP neuronal pathway.[12]

Orexin A and B

Orexins are hypothalamic peptide hormones that regulate energy balance and the sleep-wake cycle. Disordered orexin signaling has been linked to obesity, narcolepsy, and Klein–Levine syndrome.[13]

Hedonic control of appetite–food and drug reward pathways

Evidence shows that food and drug reward pathways converge within the limbic system. Stimulation of the reward centers by highly palatable foods is similar to the effects of psychoactive drugs. Dopamine is the neurotransmitter mediating these signals.[14]

Peripheral Regulation of Energy Balance

Adipocytes

Adipocytes have endocrine, immunologic, and energy balance regulatory functions. Most importantly, adipocytes secrete leptin, which suppresses appetite and helps reduce weight.

White adipose tissue in the subcutaneous and visceral regions is important in body insulation, mechanical support, and energy balance. Excess glucose is stored as triglycerides in the adipocytes during times of food surplus or low energy expenditure. States of starvation or increased energy expenditure result in triglyceride breakdown into free fatty acids and glycerol.

Brown adipose tissue is important in energy expenditure as it is the main site of adaptive thermogenesis. Mitochondria in this tissue have the transmembrane protein, uncoupling protein-1 (UCP -1), which increases heat production (thermogenesis) in response to a stimulus. Brown tissue stimulation also helps promote a negative energy balance by improving insulin sensitivity, cellular glucose consumption, and free fatty acid oxidation.

Both food ingestion and cold exposure can induce adaptive thermogenesis. In adults, brown adipose tissue is found in the supraclavicular region and upper trunk. In infants, it is abundant in the adrenal, kidney, mediastinal, and neck areas. The sympathetic nervous system promotes brown tissue-mediated thermogenesis.

Research has shown that white adipose tissue can be induced to express UCP-1 by a process called browning, which imparts brown adipose tissue-like capability for energy expenditure. The transitional adipose tissue is known as beige adipose tissue. Physiologically, browning is mediated by adrenergic stimulation, thyroid hormone, stress, and exercise. This transformation is a potential target for obesity pharmacotherapeutics.[15]

Leptin

The peptide hormone leptin is produced mainly by the adipocytes, gastric mucosa, and enterocytes. This hormone is a marker of energy stores, as triglyceride levels in the fat cells determine the level of leptin secretion. Leptin receptors (aka obesity receptors or OB-R) are found in the central nervous system, including the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus.

Leptin signals satiety. Leptin level is decreased in starvation, which increases appetite. Long-term starvation and low leptin levels also lead to decreased sympathetic nervous system output and thyroid function.

Leptin must cross the blood-brain barrier to stimulate brain receptors, including those in the hypothalamus. The arcuate nucleus is an important site of leptin action. However, leptin administration is ineffective in obese patients.[16][17]

Leptin-related conditions include the following:

- Obese individuals have elevated leptin levels despite high body fat mass, signifying leptin resistance.

- Congenital leptin deficiency is a rare syndrome characterized by hyperphagia, obesity, and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Leptin therapy can reverse obesity, increased appetite, and hypogonadism in congenital leptin deficiency syndrome.

- Leptin receptor deficiency syndrome presents similarly to congenital leptin deficiency in children. The condition does not respond to leptin therapy, though the MC4R agonist, setmelanotide, has been found to be effective in these patients.

- Lipodystrophy is marked by the loss of functional adipocytes, leading to low leptin levels. Consequently, the patient presents with increased appetite and insulin resistance reversible by leptin therapy.

Other Adipokines

Adipocytes have immunoregulatory functions apart from their role in energy balance. These cells also secrete inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and interleukin-6. Adiponectin is an adipokine that reduces insulin resistance and inflammation. Resistin is an adipokine that increases insulin resistance and inflammatory responses.[18]

Cannabinoid Receptors

The cannabinoid receptors CB-1 and CB-2 are involved in the browning of white adipose tissue. CB-1 is mainly expressed in the central nervous system, and its inhibition leads to appetite suppression and weight loss. CB-2 is expressed by the muscles, white adipose tissue, and white blood cells and is important in the inflammatory response. These receptors have gained considerable attention as potential targets for obesity treatment.[19]

Pancreatic Hormones

- Insulin: The β-islet product insulin has appetite-suppressing effects, as it inhibits NPY/AgRP neurons. Like leptin, insulin must cross the blood-brain barrier to stimulate the hypothalamus and other brain nuclei. Insulin is not as potent as leptin in suppressing appetite. Obesity-related insulin resistance blocks centrally mediated weight loss.[20]

- Pancreatic polypeptide: This molecule is secreted by the F cells in response to caloric intake. Pancreatic polypeptide slows gastric emptying and suppresses appetite by inhibiting the hypothalamic NPY/AgRP system. Pathologically low levels of this peptide are seen in obesity and Prader-Willi syndrome.

- Amylin: This hormone is also secreted by the pancreatic β-islets. Amylin increases leptin and insulin sensitivity, slows gastric emptying, and suppresses glucagon production during hepatic gluconeogenesis.

Estrogen

Post-menopausal hypoestrogenemia or estrogen level decline is associated with obesity and central fat accumulation. This condition leads to increased food intake and reduced energy expenditure. Estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) has been implicated in mediating estrogen's effect on weight regulation. This receptor isoform is expressed in the arcuate nucleus, paraventricular nucleus, and ventromedial nucleus in the hypothalamus, and the brainstem's nucleus of the solitary tract. Activation of ERα has been shown to mediate satiety and greater physical activity in animal models.

Ghrelin

Ghrelin's actions are both central and peripheral. This substance may be partly responsible for the hedonistic drive to eat, as it stimulates the food reward pathway. Ghrelin also increases insulin secretion and sensitivity, induces thermogenesis, and has a role in the sleep-wake cycle.

The mucosa of the empty stomach secretes ghrelin, and ingesting food suppresses its release. Ghrelin suppression varies with the type of food ingested and the circadian rhythm. This molecule has also been called the "hunger hormone." Patients with Prader-Willi syndrome have elevated ghrelin levels.[21]

Cholecystokinin

Cholecystokinin (CCK) is released from the duodenum and the jejunum in response to protein and fat absorption. This hormone slows down gastric emptying, stimulates gallbladder contraction, and suppresses food intake by signaling the hypothalamus. CCK acts through CCK–1 receptors in the gastrointestinal tract and CCK-2 receptors in the central nervous system.

Incretins

- Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1): This hormone is secreted by the L cells in the ileum and colon after direct contact with fat, protein, and glucose and neuronal input from the proximal intestine. GLP-1 has a variety of peripheral and central effects. This hormone promotes satiety by its action on hypothalamic nuclei and gut vagal afferents. GLP-1 stimulates glucose-dependent insulin release from the pancreas, slows gastric emptying, and suppresses gluconeogenesis by inhibiting glucagon release. Naturally secreted GLP-1 has a half-life of around 5 minutes, owing to rapid breakdown by dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) enzyme in the target tissues. GLP-1 and DPP-4 are novel therapeutic targets in treating diabetes and obesity. GLP-1 levels are lower in obesity, prediabetes, and diabetes. Improved glycemic control has been observed in post-gastric bypass surgery patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, as the procedure enhances GLP-1 levels.[22]

- Peptide YY (PYY): PYY is also secreted by the ileal and colonic L cells and has a similar appetite-suppressing effect as GLP-1. DPP-4 also degrades this molecule.

- Glucagon-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP): GIP is an incretin similar to GLP-1. This hormone is secreted by the K cells in the proximal duodenum in response to glucose and fat absorption. GIP promotes triglyceride formation in adipose tissue. DPP-4 also degrades GIP. Tirzepatide is an FDA-approved combined GLP-1-GIP medication indicated for glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. One of the drug's secondary effects is weight reduction.[19][34]

- Oxyntomodulin: This incretin is secreted by the L cells in the ileum and colon postmeal. Oxyntomodulin activates GLP-1 and glucagon receptors. This hormone suppresses appetite and increases energy expenditure.

Sympathetic Nervous System

The sympathetic nervous system regulates energy expenditure by activating thermogenesis in response to food intake, hyperinsulinemia, and cold exposure. Sympathetic activation enhances glycogenolysis and lipolysis in the fed state but stimulates gluconeogenesis in starved states.

Leptin stimulates sympathetic outflow to increase energy expenditure. High leptin levels associated with leptin resistance lead to chronic sympathetic stimulation. Obesity-related adverse cardiovascular effects, including hypertension, may be attributed to chronic sympathetic overflow.[23]

Brain-Gut Connection

During a meal, the central nervous system gets signals from vagal afferents and various peripheral tissue hormones passing through the blood-brain barrier. Processes that can increase appetite also occur outside of the system described above. For instance, the brain stem receives information from taste receptors when food enters the oral cavity. Different brain nuclei also receive olfactory information essential to the hedonic drive of eating.[20]

Gut Microbiome

This component is not an inherent part of the human body, but the gut microbiome's impact on weight regulation is nonetheless significant. Gut microflora metabolizes carbohydrates, proteins, and fatty acids. Research has shown an association between altered gut bacterial diversity and obesity.[24]

Function

Regulation of Energy Expenditure

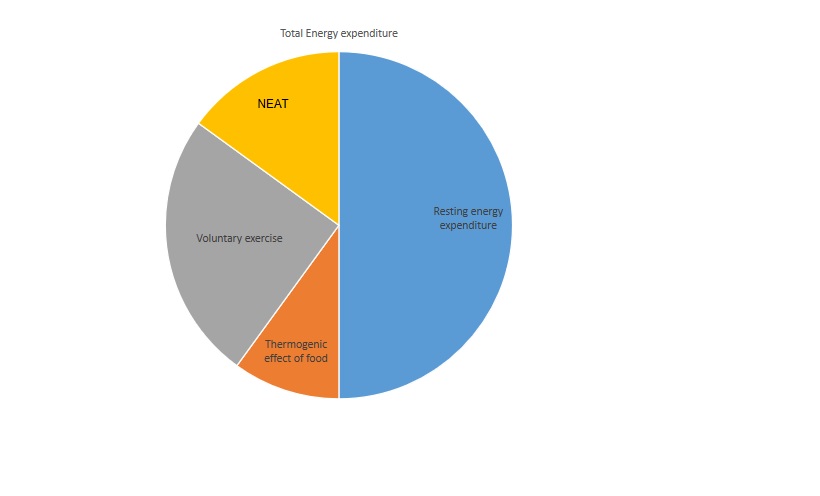

The body maintains a set point for weight and fat mass (aka, adiposity) by regulating food intake and energy expenditure.[25] The 3 major components of total energy expenditure (TEE) are explained below (see Image. Total Energy and Expenditure Components).

Resting Energy Expenditure (REE) or Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)

REE or BMR includes sleeping-related and arousal-related energy expenditure. REE is the biggest component of total energy expenditure, as it represents the energy required to maintain the human body. Age, sex, body composition, and genetics determine REE value. The thyroid hormone and sympathetic nervous system enhance REE.

Fat-free mass is the strongest predictor of resting metabolic rate. Meanwhile, roughly 5% of REE is utilized to maintain arousal. Environmental and internal body temperature also affect REE.

The Harris-and-Benedict BMR equation differs for men and women:[26]

- For men: 88.362 + (13.397 x weight in kg) + (4.799 x height in cm) - (5.677 x age in years )

- For women: 447.593 + (9.247 x weight in kg) + (3.098 x height in cm) - (4.33 x age in years )

Diet-induced Energy Expenditure—thermogenic Effect of Food

On average, 8-10% of TEE is used to process food. The thermic energy of nutrition (TEN) is the increase in energy expenditure from metabolizing nutrients, which varies by food composition. Carbohydrates require 5-10% TEN, fat needs 0-3% TEN, and protein requires 20-30% TEN.[27]

Physical activity-induced Energy Expenditure

Activity-induced energy expenditure is the most variable TEE component. Major contributors include voluntary exercise and non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT). Physical activity energy expenditure varies from 15% in a very sedentary person to 50% in a highly active individual. Sources of NEAT include walking to work and daily spontaneous movements like writing, fidgeting, and lifting loads.

NEAT is regulated by orexin via hypothalamic stimulation. Individuals with higher NEAT are less likely to gain weight.

Clinical Significance

Weight regulation disorders manifest as extreme chronic weight changes with concomitant metabolic derangements. On one extreme is obesity, a condition marked by chronic caloric excess and weight gain. On the other is malnutrition, characterized by severe weight loss or poor weight gain from a chronically negative energy balance. Nutrient deficiencies commonly accompany malnutrition. Both obesity and malnutrition can result from the failure of central and peripheral body weight regulators.

Obesity

Obesity is an emerging epidemic in the modern world. The worldwide adult obesity burden has increased by 27.5% in the last 3 decades.[28] The CDC reports that this condition had a prevalence rate of 42.4% in the United States from 2017 to 2018. Appetite regulation plays a huge role in the development of obesity. The condition has various complications, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disorders, osteoarthritis, and obstructive sleep apnea.

Sleep disorders increase the risk of obesity and diabetes. Sleep deprivation and poor sleep quality increase appetite by reducing leptin and upregulating ghrelin and orexin. Sleep-deprived individuals also have reduced thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Chronic psychosocial stress positively correlates with weight gain. The sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis are chronically hyperactive, leading to insulin resistance, hypercortisolism, central adiposity, visceral adiposity, and a preference for energy-dense foods.[29]

The first line of therapy for weight management is lifestyle change and behavior modification, which may also involve cognitive behavioral therapy. Obesogenic factors must be identified and addressed in a multidisciplinary approach.[30] Clinically, a 5-10% weight loss leads to significant cardiometabolic improvement and must be achieved in 3-6 months before considering more aggressive strategies.

The second line of therapy is pharmacotherapy. Anti-obesity medications target various mechanisms promoting chronic caloric excess. For example, orlistat inhibits lipase action, blocking gastrointestinal fat absorption. The drug combinations phentermine/topiramate and naltrexone/bupropion target the brain's appetite-control centers. Incretin medications like tirzepatide and the GLP-1 analog semaglutide act centrally and peripherally.[31][32][34][35]

Surgery is an option when health goals are not achieved after several months of lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy. Techniques for weight loss include vertical gastric sleeve, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding.

The vertical gastric sleeve decreases food intake by reducing stomach size. Ghrelin secretion abates, leading to appetite suppression. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure achieves the highest weight benefit. Besides limiting nutrient absorption, post-surgical effects include increased GLP-1 secretion and improved glycemic control. Adjustable gastric bands also decrease stomach size.[33]

Malnutrition

Severe weight loss may be unintentional or intentional. Unintentional causes result from food insufficiency and disease. Eating disorders are the most common cause of intentional weight loss.

Kwashiorkor and marasmus are conditions characterized by protein-energy malnutrition and associated with poor socioeconomic status. Young children are the most vulnerable. Kwashiorkor presents with widespread edema owing to severe protein deficiency.[36] Marasmus is marked by emaciation but has a better prognosis than kwashiorkor.[37] Both may be accompanied by vitamin deficiencies. Patients must be evaluated for emergent conditions like sepsis and heart failure and subsequently stabilized. Management includes careful refeeding, vitamin supplementation, treatment of co-existing illnesses, physical therapy, and guardian and patient education.

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are eating disorders affecting young women more than men. About 5 million Americans are diagnosed with an eating disorder every year. Anorexia nervosa patients have a history of severe fasting, excessive physical activity, or both. Being underweight is common. Bulimia nervosa patients are more likely to binge before purging or engaging in excessive physical activity. Body weight may be below normal, normal, or above normal. Management should address nutritional deficiencies and the underlying mental health condition.