Continuing Education Activity

Congenital lacrimal fistula is an uncommon condition that should be suspected both in pediatric and adult populations presenting with persistent epiphora without any other acknowledged causes. In some cases, the course of such abnormal ducts may be blinded and not in communication with the skin, which may render the clinical presentation occult. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of congenital lacrimal fistula and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Outline the typical presentation of a patient with a congenital lacrimal fistula.

- Explain the common physical exam findings associated with congenital lacrimal fistula.

- Identify the indications for surgical intervention for congenital lacrimal fistula.

- Summarize the management consideration for patients with congenital lacrimal fistula.

Introduction

Congenital lacrimal fistula is an uncommon developmental condition consisting of an accessory or anlage canaliculi between the lacrimal system and the skin. In some cases, the course of such abnormal ducts may be blinded and not in communication with the skin, which may render the clinical presentation occult.[1]

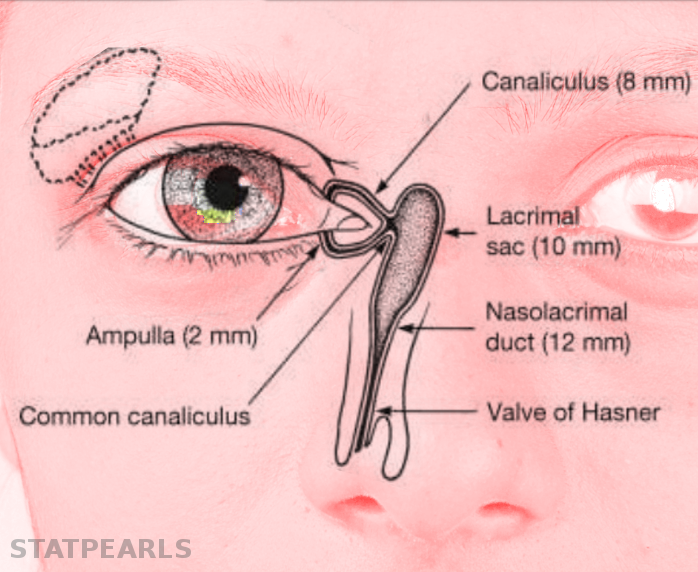

Congenital lacrimal fistulae classification is based on the origin point of its tract, which may derive from the common canaliculus, the lacrimal sac, or the nasolacrimal duct.[2]

Etiology

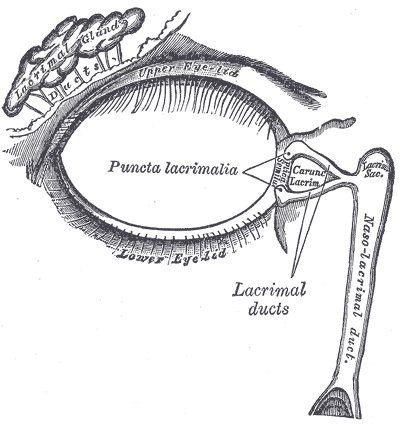

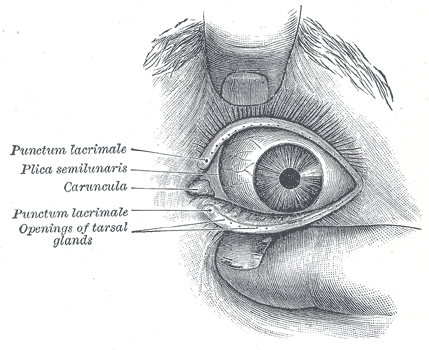

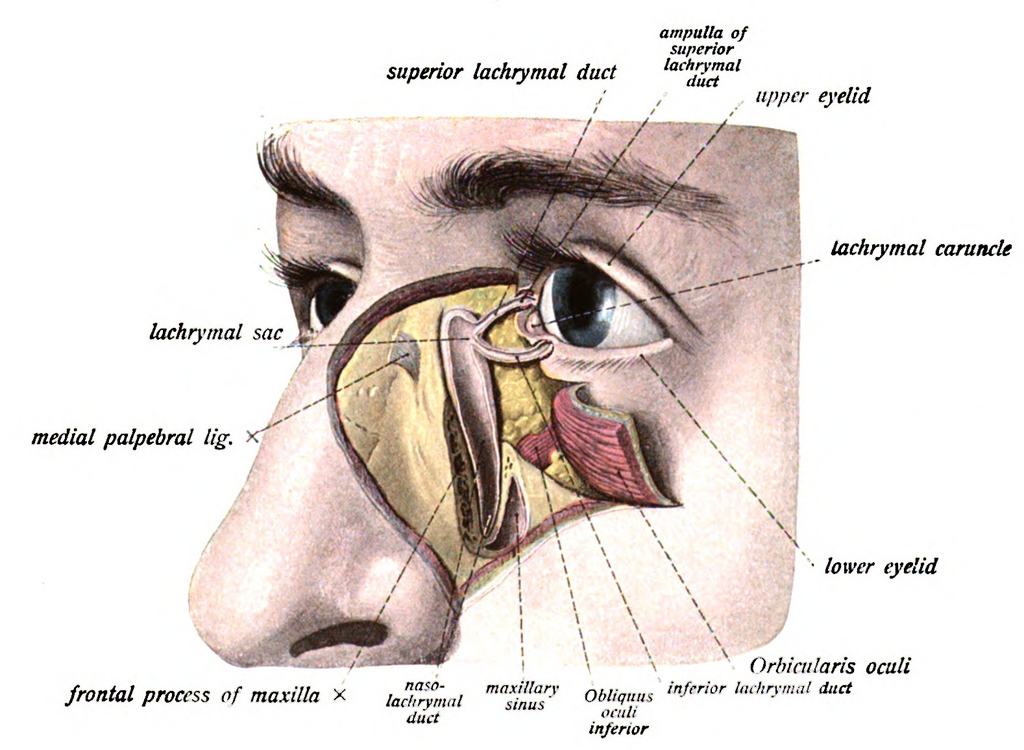

The normal adult anatomy of the lacrimal apparatus includes the puncta lacimalia, lacrimal ducts, nasolacrimal ducts, sac, and lacrimal glands (See figures of the lacrimal apparatus). To understand the pathogenesis of congenital lacrimal fistula, it is mandatory to refer to the embryology of the lacrimal system.

The nasolacrimal ducts originate from an ectodermal thickening around the naso-optic fissure in the early 32-day-old embryo. Canalization begins in the 60-day-old embryo, progressing in a caudal direction. Puncta lacrimalia can be found in the seventh fetal month. At birth, only 30% or less of infants have a patent distal nasolacrimal duct.[3]

In this developmental process, many hypotheses have been formulated to elucidate the etiopathogenesis of congenital lacrimal fistulae. Some authors have proposed that the fistula derives from excessive growth of the external wall of the nasolacrimal duct, an abnormal closure of the embryonic fissure, and amniotic bands. A phlogistic process may be involved in the formation of acquired fistulae, including purulent dacryocystitis.

Other authors have pointed out that fistula may originate from a failure in the involution process of lacrimal anlage with a possible aberrant canalization of this cord of cells. Other studies emphasized the role of a dysfunctional fusion of surface ectoderm after invagination of the ectodermal thickening. All these hypotheses converge on the assumption that anlage ducts persist when lacrimal duct cells fail to involute and continue to canalize in abnormal sites.[4]

Epidemiology

The estimated incidence is 1 in every 2000 births without any sex predominance; however, these data might be altered by a referral bias, with a possible underestimation.[5] It is known that congenital lacrimal fistulae might be inherited with both autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive mechanisms, as well as within complex multifactorial syndromes. Congenital lacrimal fistulae do not seem to exhibit any ethnic predilection. A more evident tendency to bilaterality is present for cases arising within syndromes.[6]

Histopathology

Limited literature reports a histopathological correlation between anlage ducts and congenital lacrimal fistulae. The most common finding in numerous studies is a hypertrophic squamous epithelium lining. Occasionally, translational epithelium and granulation tissue have been reported.[7]

Anecdotal reports have reported a columnar epithelium with intervening goblet cells. Subepithelial layers are generally affected by a chronic inflammatory process with infiltration or fibrosis. The epithelium lining with the lacrimal sac generally transforms into cuboidal cells.[8]

History and Physical

The typical site of presentation is inferior and nasal to the medial canthus, with the majority being unilateral. The surrounding skin usually shows redness and tenderness, with mucous or purulent secretion. In the most frequent scenario, congenital lacrimal fistulae do not cause any symptoms, and they are frequently missed because of the very narrow orifice, whereas symptomatic cases may present with epiphora or mucous secretion from the fistula or the eye, especially with a concomitant nasolacrimal duct obstruction, with possible subsequent dacryocystitis.[9]

Blepharitis may develop due to chronic inflammation, leading to redness and swelling of the eyelid. Most patients with epiphora have symptoms since birth, although a minor percentage of patients refer to late-onset symptomatology associated with intermittent nasolacrimal duct obstruction. The palpatory sensation of fullness might signify a concomitant mucocele developing within the lacrimal sac.[10][11]

The clinical examination remains the main stage of the diagnostic approach, although it has the limit that many asymptomatic fistulae, especially if non communicating with the external skin, are sometimes not diagnosed. A useful finding in children is that continuous tearing may be observed from the abnormal site when the child cries. Irrigation of the lacrimal system using a salt solution with fluorescein can enhance the visualization of any skin ostium and is also used to check if the nasolacrimal duct is patent.

Another effective aid is provided by the Valsalva maneuver, which may emphasize the discharge of purulent secretion from the fistula orifice. Other abnormalities that every clinician should be aware of include complete or partial lacrimal agenesis, incomplete punctal canalization with a non-patent drainage system, duplication of canalicula, obstruction of nasolacrimal ducts, and accessory puncta. Several studies have reported a higher frequency of hypertelorism and strabismus in such patients, especially in syndromic cases.

It is interesting to note a peculiar diagnostic finding that can be found during the clinical examination. In cases with congenital lacrimal fistulae associated with craniofacial cleft syndromes, such as Goldenhar syndrome or CHARGE syndrome, congenital eye malformations or eyelid colobomas may coexist.[8]

Evaluation

The most common methods of diagnostic investigation include probing, irrigation, and washing of the lacrimal system and radiological methods with dacryocystography or nuclear scintigraphy.

At first presentation, gentle probing of the fistula orifice is performed in an office setting, with subsequent irrigation. The fluorescein dye disappearance test may be used in children, which would generally be uncompliant to probing and irrigation.

In an uncommon clinical setting, as described by several studies, more advanced techniques have been used, including dacryocystoendoscopy, computerized tomography with contrast media injected within the lacrimal system, and casting with polyvinyl siloxane. The latter method is quite uncommon, but according to some reports, it may help create three-dimensional models of the lacrimal system. In some cases, the dacryocystoendoscope aids in visualizing the normal lacrimal anatomy and positioning a silicone drainage tube, thus facilitating eventual fistula excision.[7][12]

In some reports, methylene blue has been suggested to trace the fistula's path, especially during surgery.[13][14]

Treatment / Management

Conservative treatment is preferred for asymptomatic fistulae, especially when not associated with nasolacrimal duct obstruction.

Regarding invasive treatments, the literature reports techniques such as nasolacrimal duct probing, cautery ablation of the external ostium, and surgical excision of the fistula with or without intervening dacryocystorhinostomy. However, there are some controversies concerning the efficacy of dacryocystorhinostomy. Nowadays, the use of cautery has become more cautious and less popular due to its unsatisfactory success rate and tendency to relapse. Moreover, before making the excision of the fistula, it is important to assess the patency of the proper lacrimal system to avoid the risk of postprocedural epiphora and dacryocystitis.[2]

Probing the nasolacrimal duct is recommended when there is a concomitant obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct. Procedures such as simple probing and cauterization may be highly risky, especially if the fistula takes origin from the common lacrimal canaliculus, with the persistence of epiphora of variable degree owing to the damage to underlying lacrimal ducts.[15]

Concerning fistulectomy, this procedure can be performed in association or not with dacryocystorhinostomy. When the fistulous tract is excised externally, it is considered a closed fistula excision, whereas, in association with dacryocystorhinostomy, it is regarded as an open excision.[16]

Dacryocystorhinostomy was initially described based on an external approach. The advantage of this technique is that it allows the complete excision of the fistulous tract and optimal visualization of the internal ostium. Moreover, any nasolacrimal duct obstructions can be managed by bypassing the duct. Several studies have recommended external dacryocystorhinostomy, fistula excision, and canalicular intubation to manage symptomatic fistulae.

A modification to external dacryocystorhinostomy, less invasive, is the endoscopic technique, in which there is the creation of a bone window on the medial wall of the lacrimal socket marsupialization of the lacrimal sac in the middle meatus. This technique improves the visualization of the internal ostium, more radical removal of the fistulous tract, and avoids the creation of an unaesthetic scar on the medial canthal region.[17][18]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis (see the figure of conditions that can cause epiphora) should include the evaluation of acquired lacrimal sac fistulae, which tend to occur after the spontaneous drainage of a lacrimal abscess with a history of trauma, such as a naso-orbito-ethmoidal centrofacial fracture. Other conditions may include anatomical abnormalities of the lacrimal apparatus, such as congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction and mucoceles, which may cause chronic epiphora, mimicking a congenital lacrimal fistula.[19]

Isolated lacrimal fistulae should be differentiated from fistulae in the context of Down syndrome, VACTERL (vertebral defects, anal atresia, tracheoesophageal fistula, esophageal atresia, and radial dysplasia) syndrome, and from those arising in clefting syndromes, such as EEC (ectrodactyly–ectodermal dysplasia–cleft syndrome). Another differential diagnosis to consider is the coexistence with CHARGE (coloboma, refractive errors, strabismus, microphthalmia, and ocular movement disorders) syndrome.[20][21]

Prognosis

According to the most extensive series, recurrence of the fistulous tract is reported with an 11% rate. However, the exact calculation is difficult to perform owing to a heterogeneous origin.

Complications

Recurrence is the most severe and tedious complication; others include infection with subsequent dacryocystitis, unfavorable cosmesis, bleeding, and damage to eyelid structures.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated to visit their consultant in cases of persistent tearing, sudden infection around the medial canthal area, and dacryocystitis, especially in the pediatric age group. Incomplete literature data suffer from a reporting bias because many cases go undiagnosed.[22]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cooperation between pediatricians, general practitioners (including mid-level practitioners), and ophthalmology specialists is fundamental for the early interception of cases of congenital lacrimal fistula. Surgery may require other professionals to join the multispecialty teams, including maxillofacial and ENT surgeons, especially when a dacryocystorhinostomy is considered. Interprofessional communication and care coordination between health figures, especially for the pediatric age or for complex syndromic cases, should be enhanced for the improved management of the patient.