Continuing Education Activity

Factor V deficiency is a rare bleeding disorder that can be inherited or acquired. Factor V is a vital component of the coagulation cascade, a glycoprotein synthesized primarily in the liver and released in the bloodstream in an inactive form. Blood vessel injury activates blood clotting factors, including factor V. Activated factor V ultimately accelerates fibrinogen conversion to fibrin, the protein meshwork that reinforces the clot. Factor V deficiency disrupts this intricate clotting mechanism, impairing the body's ability to form stable blood clots efficiently. Symptoms can range from mild mucosal bleeding to severe, life-threatening hemorrhage. Diagnosis usually requires a coagulation profile and blood tests to measure the level and activity of various coagulation components, including factor V. Genetic testing may also be performed in people with the inherited form to identify the specific genetic mutation responsible for the disorder and guide family planning decisions.

Treatment typically involves managing and preventing bleeding episodes through various strategies, including clotting factor replacement therapy using agents like fresh frozen plasma. Immunosuppression may be necessary in patients with the acquired disease type. This activity for healthcare professionals is designed to enhance learners' competence in evaluating and managing factor V deficiency. Participants gain a better grasp of the condition's pathophysiology, presentations, and evidence-based diagnostic and treatment strategies. Learners become prepared to collaborate with an interprofessional team caring for individuals with factor V deficiency.

Objectives:

Identify the signs and symptoms suggestive of factor V deficiency.

Create a clinically sound diagnostic strategy for an individual with possible factor V deficiency.

Implement a personalized management plan for a patient diagnosed with factor V deficiency.

Implement interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance factor V deficiency treatment and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Factor V deficiency, also known as Owren disease or parahemophilia, is a rare bleeding disorder that may be inherited or acquired. Dr. Paul Owren first identified the condition in Norway in 1943.[1][2] The disease manifests itself similarly to other clotting factor deficiencies, with symptoms ranging from minor mucosal bleeding to severe and life-threatening hemorrhages.[3] The severity of bleeding generally correlates with factor Va levels. However, literature reports that factor Va levels below 1% may still manifest with only mild bleeding symptoms in some individuals.[4][5]

Factor V deficiency may be categorized into mild, moderate, or severe based on factor V plasma activity levels relative to the normal. Mild deficiency exceeds 10% of the normal activity level in plasma. Moderate deficiency has 1% to 10%. Severe deficiency has less than 1%. Initial laboratory values show a prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) with a normal thrombin time (TT). A low plasma factor V level can confirm the diagnosis.

Plasma mixing studies help distinguish between inherited and acquired factor V deficiency. These tests assess whether the prolonged coagulation studies result from a factor deficiency or an inhibitor. Normal plasma is combined with the patient's plasma, which exhibits prolonged PT and aPTT. Improvement of these parameters after mixing suggests an inherited form, with normal plasma replacing the missing factor. Persistent PT and aPTT prolongation after mixing indicates an acquired form, as an inhibitor in the patient's plasma prevents normalization. The test is not specific to factor V deficiency.[6]

Treatment varies based on whether factor V deficiency is inherited or acquired. In inherited cases, treatment typically involves transfusing fresh frozen plasma (FFP), which contains factor V. Mild cases may require antifibrinolytics to achieve hemostasis. In contrast, managing acquired factor V deficiency is more complex, requiring bleeding symptom control and anti-factor V autoantibody elimination. Bleeding control is achieved with transfusion of FFP, platelets, prothrombin complex concentrates, antifibrinolytics, or recombinant activating factor VII. Factor V inhibitor eradication is accomplished with immunosuppression.[7]

Coagulation Physiology

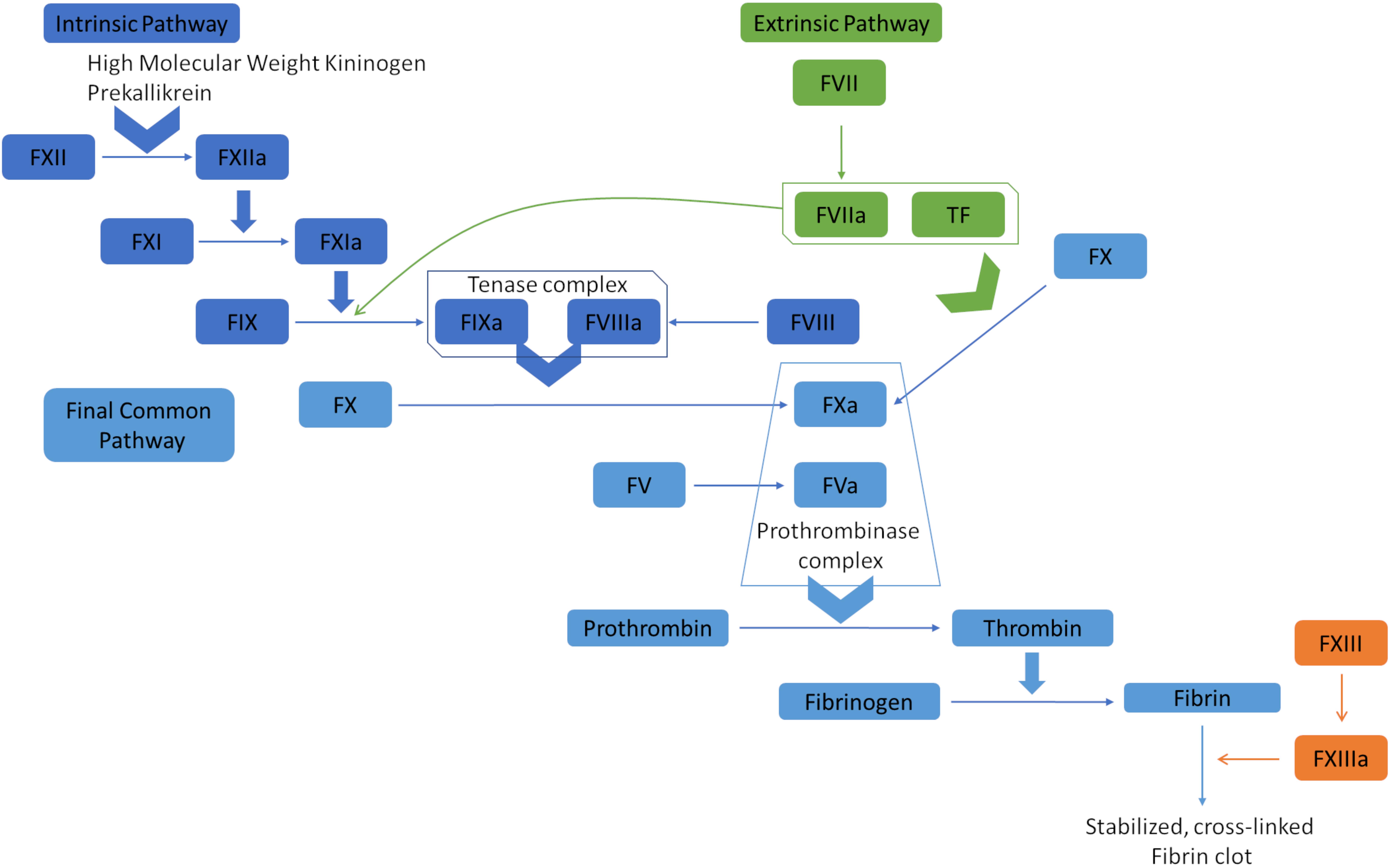

The coagulation cascade orchestrates hemostasis through the intrinsic, extrinsic, and common pathways (see Image. Coagulation Cascade Diagram). In the intrinsic pathway, endothelial damage exposes collagen, activating factor XII. This coagulation factor catalyzes the subsequent activation of factors XI, IX, and X, culminating in thrombin generation and fibrin formation. The extrinsic pathway begins when tissue factor is released by endothelial cells, activating Factor VII and merging with the intrinsic pathway to initiate factor X activation. Factor Xa subsequently catalyzes prothrombin conversion to thrombin, promoting fibrin polymerization and stabilizing the platelet plug.[8]

Factor V, also known as proaccelerin or labile factor, is a crucial nonenzymatic protein in the coagulation cascade. The liver produces approximately 80% of this glycoprotein, and the remaining 20% is synthesized within the α granules of platelets and megakaryocytes. Factor V circulates in plasma with a half-life of 12 to 36 hours.[9] Either thrombin or factor Xa converts factor V to the plasma cofactor of the prothrombinase complex. The complex is composed of calcium, phospholipids, factor Va, and factor Xa and is crucial in converting prothrombin to thrombin. Thrombin then activates factor XIII and fibrin, leading to clot formation.

Factor Va is deactivated by protein C once hemostasis is achieved. Negative feedback mechanisms modulate the coagulation cascade to prevent excessive clot formation. Despite thrombin's role in clot formation, this factor activates plasminogen to plasmin, aiding fibrinolysis. Thrombin also induces antithrombin production, which inhibits thrombin and factor Xa activity. Notably, factor V is also vital in the anticoagulation pathway. Factor V coordinates with protein C to deactivate factor VIII, decreasing prothrombinase activity and, ultimately, thrombin and fibrin production. The mechanism reduces clot production. Activated protein C (APC) shifts the balance toward coagulation inhibition.[10]

Etiology

Factor V deficiency can be either inherited or acquired. The 2 forms arise from different causes, explained below.

Inherited Factor V Deficiency

Inheritance of the condition follows an autosomal recessive pattern, with F5 gene (1q23) mutations being transmitted either homozygously or heterozygously. Heterozygous carriers are typically asymptomatic. In contrast, homozygotes and compound heterozygotes (possessing germline variants of 2 different mutations at a particular genetic locus) may exhibit a wide range of signs and symptoms, from mild to severe bleeding. Factor V deficiency is categorized into types 1 and 2. Type 1 involves a quantitative reduction in factor V activity and antigen levels. Type 2 involves qualitative dysfunction, with decreased coagulant activity whether factor V antigen levels are normal or low.[11][12] Over 190 mutations have been identified, predominantly missense and nonsense mutations, followed by small deletions, splicing mutations, and less frequently, small and large insertions, large deletions, and complex rearrangements. Symptoms typically manifest before age 6. Rarely, factor V deficiency is coinherited with Factor VIII deficiency.

Acquired Factor V Deficiency

Acquired factor V deficiency is less common than the inherited form. This condition arises from factor V inhibitor production. Risk factors include surgery involving bovine thrombin, certain antibiotics (especially β-lactams), malignancies, infections, liver disease, and autoimmune disorders. Factor V deficiency has been detected in chronic myelogenous leukemia cases, particularly during the extreme leukocytosis phase.[13] Predicting bleeding episodes for patients with this condition can be challenging, as symptoms may not consistently correlate with factor V inhibitor levels, duration of the inhibitor's presence, aPTT and PT prolongation, or factor V activity.

Epidemiology

Factor V deficiency is a rare bleeding disorder with an estimated prevalence of 1 per 1 million live births. The condition is frequently inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, affecting both sexes equally with nearly 200 confirmed mutations. While no specific ethnicity has been identified as predisposed, the condition shows increased occurrence in regions where consanguineous marriages are common.[14] Recent genetic work discovered a homozygous mutation of exon 16-Met1736Val in a family in Taiwan.[15]

Pathophysiology

Congenital factor V deficiency, though rare, can lead to uncontrolled bleeding, with triggers for spontaneous bleeding remaining unknown. In contrast, acquired factor V inhibitors are reportedly frequently triggered by exposure to bovine thrombin. Such exposure potentially results in the development of antibodies against bovine factor V that, by cross-reaction, leads to autoantibody production against human factor V.[16] While family history is crucial in genetic bleeding disorders, the absence of similar complaints in the patient's family implies a potential noninheritable factor V deficiency, though further evidence is needed. Factor V deficiency differs from the more common factor V Leiden mutation, resulting in resistance to APC and the inability to block factor V's anticoagulant effects. Individuals with factor V Leiden mutations are thus at increased risk of venous thromboembolic events.

History and Physical

History

Factor V deficiency can present with a wide array of bleeding symptoms. The inherited form can manifest in infants, while the acquired form can present at any age and may be more challenging to diagnose. When inherited, the symptoms usually appear before age 6, though some mild congenital forms may not manifest until adulthood. Bleeding due to inherited factor V deficiency is indistinguishable from other coagulation disorders.

In patients with a known family history, cord blood sampling at birth can lead to early diagnosis and intervention. Neonatal signs and symptoms reported in the literature include umbilical stump and nipple bleeding, epistaxis, gum bleeding, and subcutaneous hematomas. Life-threatening intracranial hemorrhages can also occur and often initially present as hydrocephalus and seizures in infants, warranting an immediate workup to prevent significant morbidity and mortality.[17][18]

Manifestations of factor V deficiency in older children and adults often include mucocutaneous and soft tissue bleeding such as ecchymosis, easy bruising, petechiae, epistaxis, hemoptysis, hematemesis, melena, hemarthrosis, hematuria, menorrhagia in women, and prolonged bleeding after surgery or trauma. Serious internal hemorrhage may also occur, and if not recognized early, mortality can be upwards of 15% to 20%.

For the congenital type, obtaining an accurate family history of bleeding diathesis may be key to early diagnosis. Eliciting consanguinity within the family may also help. For the acquired type, critical information includes recent surgical procedures with bovine thrombin exposure, malignancies, infections, liver disease, use of antibiotics (particularly the β-lactam group), or autoimmune disease.

Physical Examination

Bleeding in patients with factor V deficiency may be external or internal. Thus, a thorough physical examination is critical to diagnosis and management. The vital signs must be checked to assess hemodynamic status. Tachycardia and hypotension are possible signs of hemodynamic compromise in a bleeding patient. The oral and nasal cavities must be inspected for evidence of mucosal bleeding. Chest auscultation is a must for patients presenting with hemoptysis. Trauma-prone areas like the extremities must be inspected for ecchymoses, petechiae, or subcutaneous hematomas. The genitals should also be examined, especially in individuals with hematuria or menorrhagia.

People presenting with hematemesis or melena require a detailed abdominal assessment with a digital rectal examination. Abdominal tenderness or distension may be appreciated. Patients with neurological manifestations, such as seizures, altered mental status, or focal neurological deficits, should have a detailed neurological assessment. A bulging anterior fontanelle is a sign of increased intracranial pressure in infants. Unresponsiveness, apnea, and pulselessness are signs of cardiorespiratory arrest. Resuscitation measures must be initiated immediately for patients with this presentation, regardless of the cause.

Evaluation

Laboratory evaluation should be initiated when clinical findings suggest a bleeding disorder. Studies that may yield the appropriate diagnosis include coagulation tests, factor assays, inhibitor screening, and molecular genetics, as explained below.

Coagulation Tests

Factor V deficiency prolongs both PT and aPTT but leaves TT unaffected. These prolonged clotting times are not specific to factor V deficiency but suggest a defect within the common pathway. Additional testing for other common pathway factors like fibrinogen, factor II, and factor X is necessary to specify the problem. Liver disease can also prolong PT and aPTT due to decreased clotting factor synthesis. Following factor V deficiency confirmation, mixing studies aid in distinguishing between a lack of factor V and the presence of an anti-factor V inhibitor. Normal clotting times after mixing indicate factor V deficiency, while failure to correct suggests the presence of an inhibitor.

Factor Assays

Factor V assays reveal reduced activity levels, with the deficiency categorized into mild (>10%), moderate (1%-10%), or severe (<1%). All factor activity levels should be measured to identify if a coexisting deficiency exists, as in combined factors V and VIII deficiency.

Inhibitor Screening

Nonspecific inhibitors commonly used for screening include lupus anticoagulant and ELISA testing against β-2 glycoprotein and cardiolipin antibodies, which may be elevated in acquired factor V deficiency. The Bethesda assay, measuring inhibitors against a specific factor in the blood, confirms this diagnosis.

Molecular Genetic Analysis

The F5 gene, situated on chromosome 1q24.2 and spanning 25 exomes, consists of 6 domains: A1, A2, A3, B, C1, and C2. Sequencing deoxyribonucleic acid from peripheral blood leukocytes helps identify mutations within this gene to diagnose inherited factor V deficiency. Missense mutations, predominantly found (61.5%) at domains A2 and C2, are common, with an additional 20% occurring at the B domain. A single heterozygous mutation typically results in factor V activity levels around 50%, while homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations often lead to levels below 10%. MCFD2 and LMAN1 gene mutations cause combined factors V and VIII deficiency, as these genes are associated with the transportation of these coagulation factors.[19]

Treatment / Management

Treatment depends on the condition's etiology and severity. Mild inherited factor V deficiency may be managed with antifibrinolytics, while more severe phenotypes often require FFP transfusions to replenish factor V levels. Factor V deficiency is uncommon. Thus, a specific factor V concentrate is not commercially available for treatment. Other blood products (eg, platelets, prothrombin complex, or cryoprecipitate) contain minimal factor V. Thus, FFP is the primary therapy for moderate to severe cases. FFP therapy sustains factor V levels above 25% to 30% during bleeding episodes or invasive procedures, with elevated levels required to ensure hemostasis in severe or life-threatening hemorrhages.

Asymptomatic patients with acquired factor V deficiency do not require treatment since the inhibitors present in the blood are transient. A multifactorial approach is often necessary for patients undergoing surgery or those experiencing significant bleeding. Methods to control bleeding in this cohort include transfusion of FFP, platelets, prothrombin complex concentrate, and recombinant activated factor VII. Although the platelet α-granules contain minimal factor V, platelet transfusions alone have shown a 71% success rate in treating acquired factor V deficiency owing to protection against inhibitors and promotion of hemostasis.

Recombinant activated factor VII, commonly used to treat inhibitors in hemophilia A or B, can also effectively manage bleeding. The treatment directly activates factor X, bypassing the requirement for factor V or other factors in the coagulation cascade.[20] However, immunosuppression is the gold standard for eliminating factor V inhibitors. Options include corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab. These agents, alone or in combination, have been shown to suppress anti-factor V autoantibody production with a 63% success rate. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulins (60% success rate) and plasmapheresis (53% success rate) also reduce factor V inhibitors in the blood.[21]

Differential Diagnosis

Disorders affecting the coagulation cascade and platelet function cannot be differentiated based solely on clinical presentation. Further diagnostic tests must be performed to yield an accurate diagnosis.

Coagulation Cascade Abnormalities

Coagulation tests can distinguish various protein and factor deficiencies. Hemophilia A and B, the most common bleeding disorders, are always considered in the differential diagnosis. Hemophilia A (factor VIII deficiency), B (factor IX deficiency), and C (factor XI deficiency) typically present with isolated aPTT prolongation. These conditions can be distinguished from factor V deficiency by assessing factor VIII, IX, or XI levels alongside a normal PT. Other disorders causing prolonged PT and aPTT with a normal TT include deficiencies in common pathway factors (II or X), combined factors V and VIII co-deficiency, vitamin K-dependent clotting factors (II, VII, IX, X), or liver disease. Afibrinogenemia, hypofibrinogenemia, and dysfibrinogenemia also result in prolonged PT and aPTT, but TT is prolonged in these cases. Patients with these conditions may experience thrombotic or hemorrhagic events, though many remain asymptomatic.

Platelet Dysfunction

Von Willebrand disease is the most prevalent inherited bleeding disorder and must also be ruled out. The condition presents variably, from mild mucosal bleeding in type 1 to severe hemorrhages resembling hemophilia in type 3. Patients with von Willebrand disease may exhibit prolonged or normal aPTT, a normal PT, normal to low platelet count, and normal to low factor VIII levels. Although rare, platelet function defects like Glanzmann thrombasthenia and Bernard Soulier syndrome should likewise be considered. These disorders are characterized by normal PT and aPTT, indicating platelet adhesion and aggregation dysfunctions independent of the coagulation cascade.[22]

Prognosis

Congenital and acquired factor V deficiency are both exceedingly rare. Data are insufficient to determine the long-term prognosis of affected individuals. However, up to 21% mortality rate has been documented in patients who present with severe bleeding manifestations.

Complications

Factor V deficiency complications can occur as early as the neonatal period. While rare, intracranial hemorrhages pose diagnostic challenges in newborns and carry high mortality rates. Thrombotic events, though less frequent, may also manifest due to factor V's prothrombotic effect, with reported cases including deep vein thrombosis, cerebral infarction, and limb gangrene. Early suspicion of Factor V deficiency necessitates immediate treatment to prevent potentially life-threatening outcomes.

Consultations

A hematologist should be consulted at the earliest suspicion of a bleeding disorder. Pregnant patients with a family history of bleeding diatheses should consult a pediatric hematologist so that an accurate diagnosis can be made early. Cord blood sampling at birth can streamline the diagnosis of coagulation disorders in neonates, minimizing the need for large blood volumes. Early hematology consultation is crucial, especially in patients with active bleeding needing immediate blood product support. Timely hematology involvement ensures accurate testing before administering blood products, preventing potential diagnostic and treatment delays caused by postadministration interference with coagulation studies.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should receive counseling upon diagnosis of factor V deficiency due to the condition's rarity. Women of childbearing age must be educated regarding the condition's heritable nature and possible complications during pregnancy and delivery. Screening for hereditary factors among the proband's relatives is also essential for genetic counseling. Family members should be educated on preventive measures and potential complications before surgical procedures. An alert bracelet is crucial for swift recognition and intervention in life-threatening complications.

Preventing bleeding in patients with acquired factor V deficiency involves treating the underlying cause, such as discontinuing medications or addressing medical conditions inciting antibody formation. Careful monitoring of coagulation parameters and administering appropriate blood products, such as FFP, may be necessary to maintain adequate hemostasis and prevent bleeding episodes in affected individuals. Acquired factor V deficiency is often transient. Still, patients must be cautioned about trauma avoidance by minimizing engagement in high-risk activities like contact sports. Regardless of the etiology, affected individuals must follow up routinely with a hematologist. Close communication with healthcare providers is mandatory in case of a bleeding event.

Pearls and Other Issues

Factor V deficiency affects the coagulation cascade due to a dysfunction or deficiency of the glycoprotein. The condition may be congenital or acquired. Bleeding symptoms can vary significantly, ranging from mild to severe hemorrhages. Inherited factor V deficiency typically manifests in infancy, necessitating a thorough family history evaluation and cord blood sampling for early diagnosis. Acquired factor V deficiency can occur at any age, often due to factor V antibodies from sources like bovine thrombin, medications, and underlying conditions like liver disease and malignancies.

Coagulation studies, factor assays, inhibitor screening, and molecular genetic analysis are essential for diagnosis. Factor V deficiency treatment depends on the etiology. Inherited cases are often managed with FFP transfusions, while mild cases may benefit from antifibrinolytics. Acquired factor V deficiency treatment involves controlling bleeding symptoms and eliminating anti-factor V autoantibodies through various methods, including immunosuppression and transfusions of blood products such as FFP, platelets, or prothrombin complex concentrates. Prevention strategies involve patient education, including wearing alert bracelets for prompt recognition of the condition and minimizing trauma to reduce the risk of bleeding events.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Coordination among specialists is crucial when dealing with rare disorders like factor V deficiency. Patients with this condition require routine follow-up with a hematologist. For elective surgeries, discussions about prophylaxis and bleeding control involve collaboration between the hematologist and the surgical team. In hemorrhage-related emergencies, hematologists and transfusion medicine physicians should be promptly involved to ensure appropriate product availability. Quick pharmacy notification is necessary for urgent product requests.

Effective communication and collaboration among healthcare teams are essential for patient safety and better outcomes. Pregnant patients should be closely monitored in a high-risk obstetrics clinic due to factor V deficiency's potential complications. Counseling parents on the hereditary nature of the condition and considering a genetic consultation can be beneficial. Neonatologists and pediatricians should be vigilant about family history and disease presentation in undiagnosed pediatric cases. Prompt diagnosis of intracranial hemorrhages is crucial. The condition can be lethal if left untreated, especially when the cause is unknown.