Introduction

The teres major is a thick but flattened, rectangular muscle that extends from the inferior posterior scapula to the medial lip of the intertubercular groove of the humerus.[1][2] It functions synergistically with the latissimus dorsi to extend, adduct, and internally rotate the humerus.[3] Although the latissimus dorsi and teres major muscles often function in conjunction with one another, isolated injuries to either muscle may also occur. Injuries to the teres major are rare but may occur due to stretch or impact injuries.

Structure and Function

Anatomy

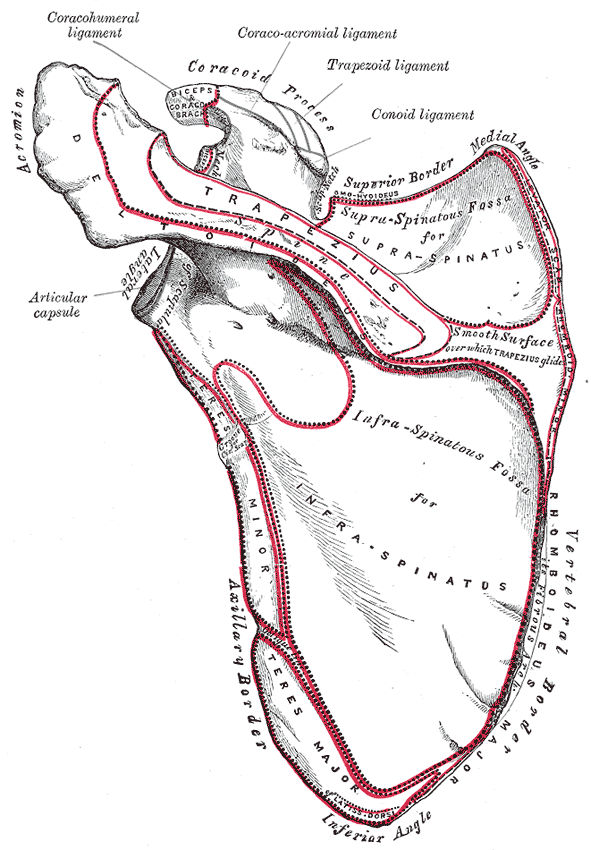

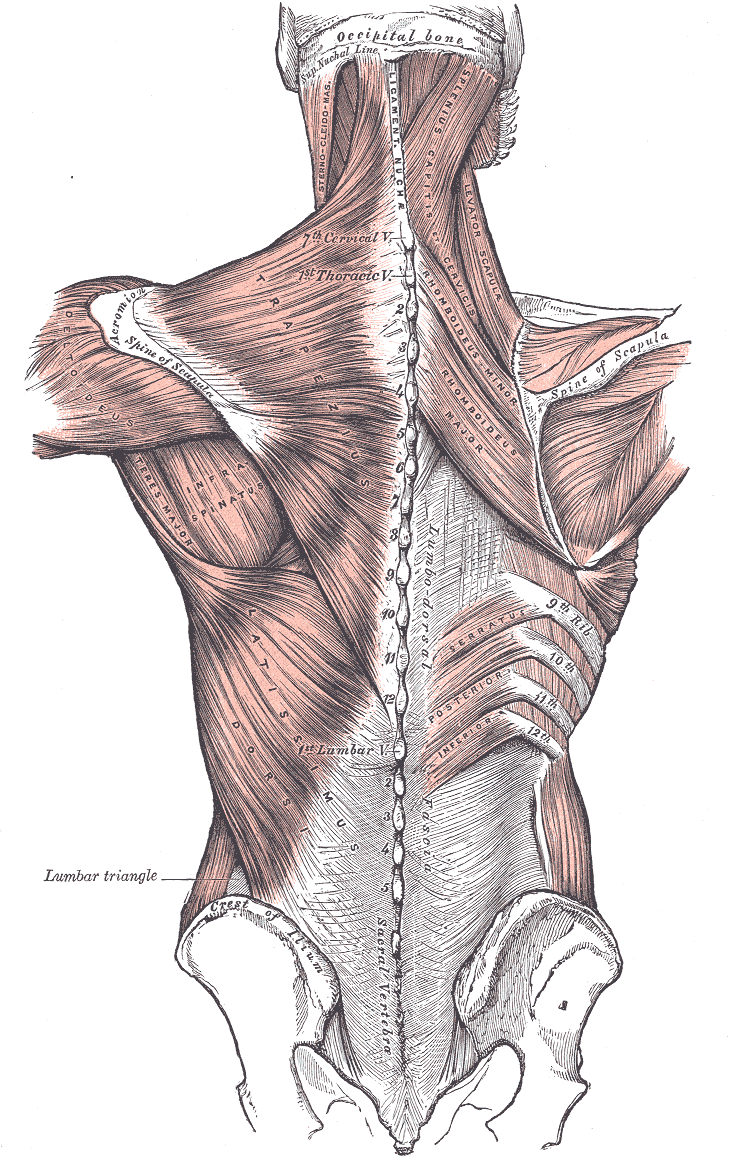

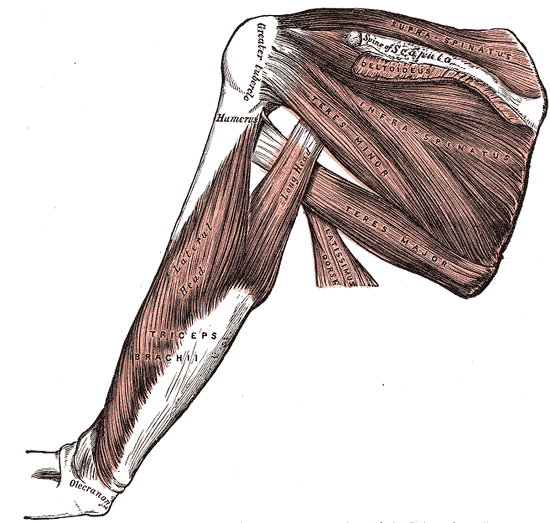

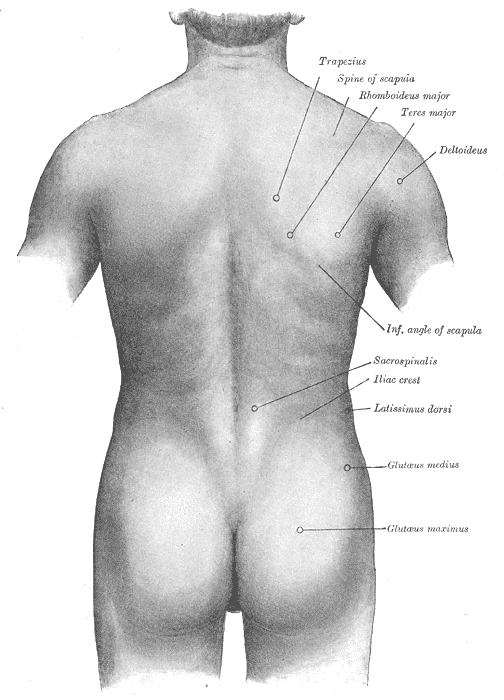

The teres major originates on the posterior surface of the inferior angle of the scapula and inserts on the medial lip of the intertubercular groove of the humerus.[4] It is located inferior to the teres minor and travels anterior to the triceps long head before inserting on the humerus.[3][2] The teres major is located deep to the deltoid muscle and makes up the posterior wall of the axilla along with the subscapularis and latissimus dorsi muscles.[5]

The latissimus dorsi originates inferior to the teres major and travels along the inferior border of the teres major. The latissimus dorsi then travels superiorly to insert at the same site on the humeral head as the teres major, the lip of the intertubercular groove of the humerus. The latissimus dorsi and teres major tendons often join near the insertion site, with some studies illustrating that the tendons fused prior to their insertion on the humerus.[6][7]

In addition to the teres major and latissimus dorsi both inserting on the lip of the intertubercular groove of the humerus, the pectoralis major also inserts at this same site except more laterally.

Function

The function of the teres major is to extend, medially rotate and adduct the humerus. It also plays a role in the stabilization of the humeral head. This muscle is not alone in these functions. The latissimus dorsi also aids in medial rotation and adduction of the humerus.[3] These two muscles function synergistically in these effects, with electromyographic studies illustrating that the two muscles activate as one muscle unit.[6]

The pectoralis major also acts to adduct the humeral head. The rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis) assist the teres major in stabilizing the humeral head.[8] Together, these muscles are crucial to preventing subluxation of the humeral head.

Embryology

The upper limb usually begins to develop around weeks four and five. Specifically, during week four, the limb bud first appears, and during week five, migration occurs, forming the anterior and posterior condensations. The latter gives rise to shoulder muscles, including both teres minor and teres major. The upper extremity muscle groups are all established by eight weeks.[9]

The teres major is part of the upper limb and arises from the paraxial mesoderm. This gives rise to the myotome. The myotome can be further divided into subpopulations, of which the primaxial myotome later develops into the teres major.[10]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The teres major is supplied by the posterior circumflex humeral artery and the thoracodorsal branch of the subscapular artery.

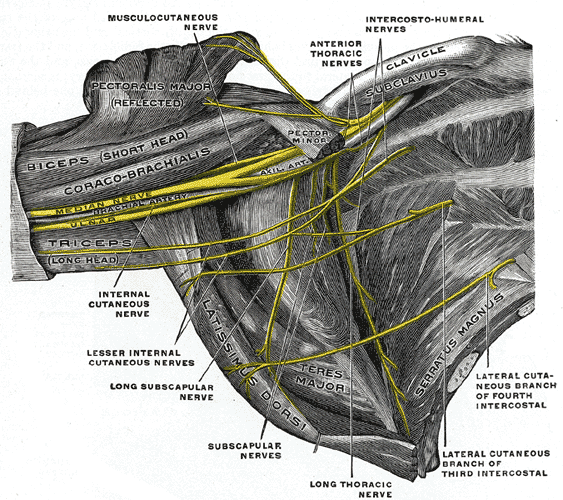

The posterior humeral circumflex artery arises from the third most distal portion of the axillary artery and travels posteriorly through the quadrangular space and around the humeral neck. The axillary nerve travels with the posterior humeral circumflex artery through the quadrangular space. The quadrangular space is made up of the teres major (superior), teres minor (inferior), long head of triceps brachii (medial), and the surgical neck of the humerus (lateral). Along its course, the posterior humeral circumflex artery supplies the teres major, teres minor, deltoid, and long head of the triceps.

The axillary artery gives rise to the subscapular artery, the largest branch of its distal portion, and supplies the latissimus dorsi along with the intercostal muscles and serratus anterior. The subscapular artery has two branches: the circumflex scapular artery and the thoracodorsal artery. This thoracodorsal artery travels inferomedially, running across the lateral angle of the scapula. Throughout its course, this artery supplies the teres major, serratus anterior, subscapularis, and latissimus dorsi.[5]

Nerves

The teres major is innervated by the lower subscapular nerve, derived from C5, C6, and C7 nerve roots.[11] This nerve branches from the brachial plexus; specifically, it is the third branch of the posterior cord, giving rise to the thoracodorsal nerve (C6, C7, C8 to the latissimus dorsi) before branching into the lower subscapular nerve.

The lower subscapular nerve runs inferiorly off the brachial plexus to innervate the subscapularis in addition to the teres major. After the posterior cord gives rise to the thoracodorsal nerve and lower subscapular nerve, it branches into the axillary and radial nerves.[12]

Muscles

The rotator cuff muscles consist of four muscles, including the teres minor, subscapularis, supraspinatus, and infraspinatus.[9] The rotator cuff muscles play an essential role in stabilizing the glenohumeral joint. Although teres major also plays a role in stabilizing the glenohumeral joint, it is not considered one of the rotator cuff muscles.

Physiologic Variants

Physiologic variants of teres major are rare but have been reported, specifically at the insertion site. Teres major inserts on the medial lip of the intertubercular groove of the humerus, where the tendon fuses with the tendon of latissimus dorsi. Variations in where the tendons fuse, both proximally and distally, have been reported in the literature.[13]

Surgeons must be aware of these variants as teres major is frequently used in tendon transfer procedures for rotator cuff repair.

Surgical Considerations

The teres major comprises the inferior border of the quadrangular space. Within this space are the axillary nerve and posterior humeral circumflex artery.[14] The superior border of this space is the teres minor. Tears to the teres minor often require surgical intervention. Therefore, it is essential for surgeons operating in this area to be aware of anatomical structures to avoid iatrogenic neurological or vascular injuries.

Although teres major is not one of the four rotator cuff muscles, it is often used in musculotendinous transfer for rotator cuff deficits. This procedure can place the radial nerve, the axillary nerve, and their branches at risk.[15] Surgeons must remain vigilant for these structures during the transfer of both the latissimus dorsi and teres major tendons during rotator cuff repair.

Isolated teres major tears are rare; they sometimes occur during sports with overhead activities like baseball, swimming, water-skiing, and tennis.[16] Unfortunately, there is limited literature describing the management of these cases. Conservative management is often the standard for teres major injuries, but surgical intervention can be performed in special cases.

Clinical Significance

Isolated Teres Major Tears

Tears of the teres major are rare and can be either acute or chronic. Patients often present with a sudden onset, sharp pain in the shoulder, proximal upper extremity, and axilla. The pain is exacerbated with physical activity and any activities in which the hand is placed posterior to the back. There will often be swelling and ecchymosis in the inferior posterior axilla. On a physical exam, there may be point tenderness to palpation over the area of the teres major. Additionally, the patient may present with weakness in extension, adduction, and internal rotation of the humerus secondary to their injury.[17]

Combined Tears

Injuries to the teres major can either be isolated or combined. Combined tears affect the teres major in addition to the latissimus dorsi. These muscles are often injured together due to their tendons joining at their common insertion point at the lip of the intertubercular groove of the humerus. These combined tears occur similarly to isolated tears and most often occur in young athletes, especially overhead athletes such as baseball pitchers.

The combined tear often presents as acute pain in the upper arm and posterior axilla with tenderness to palpation along the teres major and the latissimus dorsi. On visual inspection, ecchymosis is often present, along with slight asymmetry. The best imaging technique for assessing the injury is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These combined tears are often treated nonoperatively with rest, physical therapy, and oral anti-inflammatories.[12] Most individuals can return to their sport in a matter of months.

Strain

Strains of the teres major are also rare but may occur in sporting activities or trauma. Not warming up before exercise is a risk factor for a teres major strain. Motor vehicle accidents and falling onto the lateral border of the scapula have also been implicated in this pathology.

On physical exam, a jump sign may be elicited, which is characterized as an involuntary withdrawal of the muscle with passive internal rotation of the shoulder. The extent of the strain and differentiation from a tear can be further evaluated on a large field view magnetic resonance imaging using a specific protocol to visualize bilateral shoulder girdles. The incidence of teres major injuries may be underreported given that the majority of these injuries cause only minor disability and, therefore, may not be reported or evaluated.

Other Issues

Quadrangular Space Syndrome

This is a rare condition characterized by compression of the axillary nerve and posterior humeral circumflex artery as they travel through the quadrangular space.[18] Compression can occur from hypertrophy or fibrous bands of the teres major.[19] It is associated with athletes that participate in sports requiring frequent arm abduction and external rotation, such as baseball pitchers, swimmers, and volleyball players. Patients often present with an insidious onset of shoulder pain, shoulder weakness, and sensation loss in the area innervated by the axillary nerve.[20] In addition, patients are likely to have point tenderness at the site.

Upper-Crossed Syndrome

This syndrome is characterized by an imbalance of muscle strength, tightness, and movement patterns in the upper quarter of the body. Numerous anterior and posterior thorax muscles are implicated. Patients present with a forward head posture, thoracic spine hunching, elevated and protracted shoulders, and decreased spine mobility in the thoracic vertebrae.[21]

These postural abnormalities are associated with pain and inflammation in the back and neck. This is often caused by continual position in poor postures, such as those who spend a prolonged time using a computer, reading, or watching television. Additionally, over time, upper-crossed syndrome can lead to cervicothoracic and glenohumeral joint dysfunction.