Continuing Education Activity

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a life-threatening condition. Arterial aneurysms are defined as a permanent localized dilatation of the vessel, enlarging by at least 150% compared to a relatively normal diameter of the adjacent artery. The abdominal aortic aneurysm is characterized by abnormal focal dilation of the abdominal aorta that may be detected incidentally or at the time of rupture. Vigilant monitoring or treatment is required depending on the size of the aneurysm and symptomatic presentation. Risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm are diverse and include atherosclerosis (most common), smoking, advanced age, male sex, being part of the White population, family history of abdominal aortic aneurysm, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and prior history of aortic dissection.

The course provides healthcare professionals with comprehensive insights into the evaluation and management of abdominal aortic aneurysms, emphasizing the importance of timely detection and intervention. Participants learn evidence-based practices for screening, assessing, and monitoring patients at high risk for AAA. The course highlights the critical role of an interprofessional team in ensuring early recognition and management, ultimately improving patient outcomes. Collaboration among clinicians, such as physicians, nurses, radiologists, and other healthcare professionals, enhances the ability to detect and treat AAA effectively, reducing the likelihood of rupture and increasing the chances of favorable outcomes for patients.

Objectives:

Differentiate between symptomatic and asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysms to guide appropriate management strategies.

Apply guidelines for the management and surveillance of unruptured and ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms.

Implement evidence-based screening protocols for abdominal aortic aneurysm in clinical practice.

Collaborate and communicate with all members of the interprofessional team to improve outcomes and treatment efficacy for patients diagnosed with an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Introduction

An arterial aneurysm is defined as a permanent localized dilatation of the vessel, enlarging by at least 150% compared to the relatively normal diameter of the adjacent artery.[1] An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is an abnormal focal dilation of the abdominal aorta. This life-threatening condition requires monitoring or treatment depending on the size of the aneurysm and associated symptoms. The AAA may be detected incidentally or at the time of rupture.

Etiology

Risk factors for AAAs include atherosclerosis (the most common), smoking, advanced age, male sex, White race, family history of AAA, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and prior history of aortic dissection. Other causes include cystic medial necrosis, syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus, and connective tissue diseases (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome, and Loeys-Dietz syndrome). Those of the non White race and those with diabetes are associated with a reduced risk for AAA. Enlargement of the aneurysm can occur in a step-wise manner, with size remaining stable for some time before experiencing a rapid enlargement. The enlargement rate for small abdominal aortic aneurysms (3-5 cm) is 0.2 to 0.3 cm/year; this can range from 0.3 to 0.5 cm/year for those with a diameter greater than 5 cm.[2] The pressure on the aortic wall follows the law of Laplace (wall stress is proportional to the radius of the aneurysm). Accordingly, larger aneurysms are at a higher risk of rupture, and the presence of hypertension also increases this risk.

Epidemiology

Based on autopsy studies, the frequency of these aneurysms varies from 0.5% to 3%. The incidence of AAAs increases after age 60 and peaks in the seventh and eighth decades of life. White men have the highest risk of developing AAAs, whereas they are relatively uncommon in Asian, Black, and Hispanic individuals.[3] Data derived from Life Line Screening and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES, 2003-2006) database reveal a prevalence of 1.4% in individuals aged 50 to 84, equivalent to 1.1 million AAAs studied.[4]

With the increased use of ultrasound, diagnosis of AAA is common. Diagnosis are common in smokers and older White men. Although autopsy studies may under-represent the incidence of AAA, results from a study conducted in Malmo, Sweden revealed a prevalence of 4.3% in men and 2.1% in women as detected by ultrasound.[5]

Pathophysiology

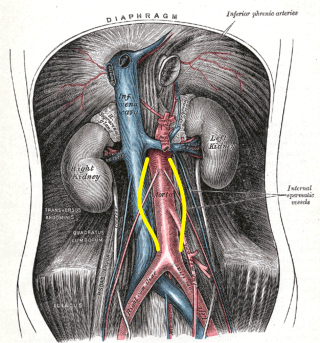

AAAs tend to occur when there is a failure of the structural proteins of the aorta. What causes these proteins to fail is unknown, but the aortic wall gradually weakens. The decrease in structural proteins of the aortic wall, such as elastin and collagen, has been identified.[6][7][8] The aortic wall is made of collagen lamellar units. The number of lamellar units is lower in the infrarenal aorta than in the thoracic aorta.[8][9][10] This is believed to contribute to the increased incidence of aneurysmal formation in the infrarenal aorta. A chronic inflammatory process has been identified in the wall of the aorta, but its cause remains unclear.[11] Other factors that may play a role in developing these aneurysms include genetics, marked inflammation, and proteolytic degradation of the connective tissue in the aortic wall.[12][13][14] See Image. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm, Illustration.

Histopathology

Autopsy studies of AAAs usually show significant degeneration of the media and typically reveal a state of chronic inflammation with an infiltrate of neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes. The media is often thin, and there is evidence of degeneration of the connective tissue.

History and Physical

Most abdominal aortic aneurysms are incidentally identified during examinations for other unrelated pathologies, and most individuals are asymptomatic. Palpation of the abdomen usually reveals a nontender, pulsatile abdominal mass. Enlarging aneurysms can cause symptoms such as abdominal, flank, or back pain; the compression of adjacent viscera can cause gastrointestinal or renal manifestations.

AAAs are life-threatening. However, the presentation of patients with this type of ruptured aneurysm can vary from subtle to dramatic. Most patients may present in shock, often exhibiting diffuse abdominal pain and distension. Patients with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm often succumb even before reaching the hospital. The patient may have tenderness over the aneurysm or demonstrate signs of embolization.

If the aneurysm ruptures into adjacent viscera or vessels, presenting findings may include gastrointestinal bleeding or congestive heart failure due to the aortocaval fistula. A physical examination should also include an assessment for other associated aneurysms, the most common being an iliac artery aneurysm. Peripheral aneurysms are also associated with approximately 5% of patients, with popliteal artery aneurysms being the most common.

Evaluation

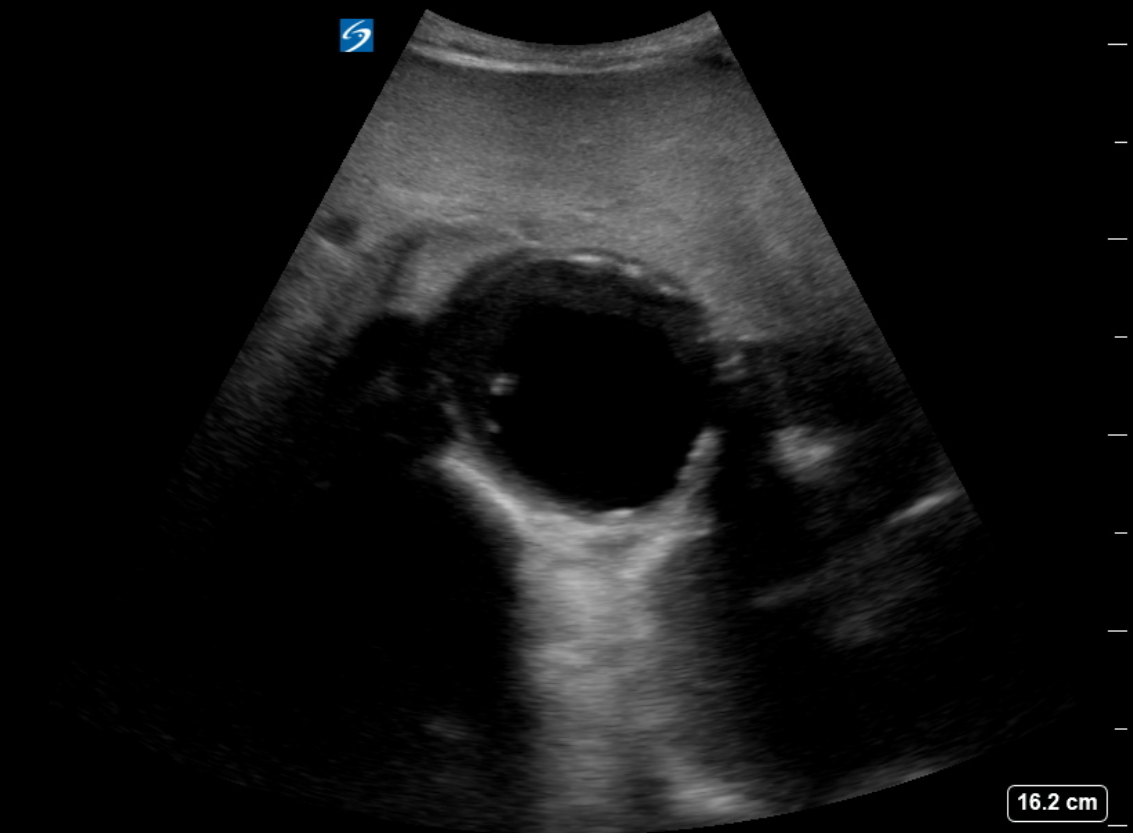

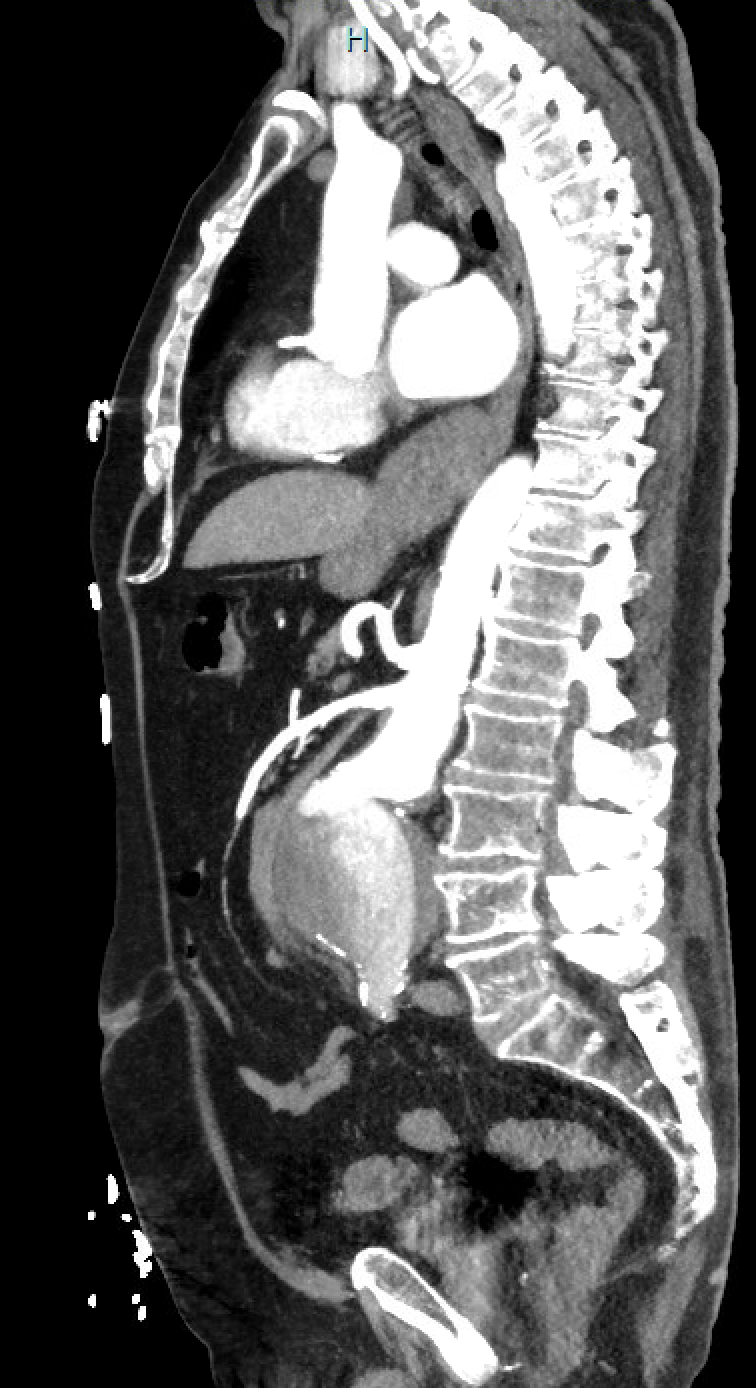

The diagnosis of an abdominal aortic aneurysm is usually made using ultrasound (see Images. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm, Ultrasound and Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm, Illustration). However, a computed tomography (CT) scan remains necessary to determine other vessels' exact location, size, and involvement and is the preferred imaging modality for symptomatic individuals. The ultrasound can be used for screening purposes but is less accurate for aneurysms located above the renal arteries due to the presence of overlying air-containing lungs and viscera. CT angiography requires ionizing radiation and intravenous contrast; however, magnetic resonance angiography can delineate the anatomy and does not require ionizing radiation.

Most of these aneurysms are located below the origin of the renal arteries and may be classified as saccular (localized) or fusiform (circumferential). More than 90% of abdominal aortic aneurysms are fusiform. Intense inflammation, a thickened peel, and adhesions to adjacent structures characterize an inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysm. Angiography is now rarely performed for diagnostic purposes due to the superior image quality achieved with CT scans.[15] See Images. Ruptured Infrarenal Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm and Infrarenal Abdominal Aneurysm, Computed Angiogram.

Magnetic resonance angiography is an option for patients with allergies to contrast media. An echocardiogram is recommended as many patients also tend to have associated heart disease. All patients require routine blood work, including a cross-match if surgery is necessary. Patients with comorbidities such as diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or heart disease should be diagnosed by the relevant specialist and cleared for surgery. Cardiovascular risk factor modification should be achieved with smoking cessation, blood pressure control, statin, antiplatelet therapy, and healthy lifestyle, including diet and exercise.[16] The previously advocated use of beta-blocker therapy has been disproven for the sole purpose of reducing the risk of AAA expansion and rupture.[17]

Treatment / Management

The treatment of unruptured AAA is recommended when the aneurysm diameter reaches 5.5 cm in men and 5.0 cm in women,[16][18] shows a rapid enlargement of greater than 0.5 cm over 6 months, or if it becomes symptomatic. Thus, according to recent guidelines from the European Society for Vascular Surgery, AAA repair is recommended if the aneurysm is symptomatic and greater than 4 cm, and has increased in size by greater than 1 cm/year, as measured by the inner-to-inner maximum anterior-posterior aortic diameter on ultrasound.[18]

Open surgical repair using the transabdominal or retroperitoneal approach has been the gold standard. Endovascular repair using a femoral arterial approach is now applied for most repairs, especially in older and higher-risk patients. Endovascular therapy is recommended for patients with cardiovascular or other comorbidities that deem them at high risk for open surgery if they have suitable anatomy. A ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm warrants emergency repair. If the anatomy is suitable, the endovascular approach for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm has shown superior results and survival rates compared to open repair, but the mortality rates remain high. See Image. Repaired Ruptured Aortic Aneurysm, Aortigram.

The patient's age, the presence of renal failure, and the status of the cardiopulmonary system influence the risk of surgery.[19][20] In cases of horseshoe kidney, which often has multiple accessory arteries originating from the aneurysm, or when there is a concomitant iliac artery aneurysm where preservation of the hypogastric artery is necessary, and the anatomy is not suitable for an iliac branch endoprosthesis, open repair may be the most suitable option. This approach allows for reimplanting branches that an endograft would otherwise cover. The choice of a transabdominal or retroperitoneal open approach for an infrarenal aortic aneurysm depends upon the comfort level of the operator; however, access to the right renal artery and right external iliac artery is challenging from a retroperitoneal approach and may be better addressed via a transperitoneal approach. There is an advantage to the retroperitoneal approach for pararenal or suprarenal aneurysms, as the left kidney can be mobilized, improving exposure.

Data show that endovascular repair has no long-term differences in outcomes for unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms compared to open repair. However, data indicate that expansion of the neck of the aorta continues despite endovascular therapy, which can lead to device failure. This is less common when the patient's anatomic measurements are within the selected endograft device's instructions for use (IFU). The most recent 2024 European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) guidelines advise against endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) outside the manufacturer's IFU in the elective setting.[16] Results from a large Vascular Quality Initiative study with 50,411 patients who had undergone EVAR AAA either with or without post-operative beta-blockers (BBs) demonstrated that patients on BBs do not have a reduced incidence of endovascular reinterventions after EVAR and have a higher mortality risk.[21]

Open repair has been the gold standard for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair for many decades. This procedure involves a long midline incision followed by replacing the diseased aorta with a graft. Postoperatively, these patients need close monitoring in the intensive care unit for 24 to 48 hours. Due to the less invasive nature of EVAR, this remains the preferred approach when most patients consider it feasible. All patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms who do not undergo repair need periodic follow-up with an ultrasound every 6 to 12 months to ensure that the aneurysm is not expanding. The size of the AAA dictates the frequency.[22]

Traditionally, the anatomic eligibility for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair is based on 3 major anatomic factors—the proximal aortic neck, common iliac arteries, and external iliac arteries. The mentioned index areas characterize the proximal and distal landing zones. A successful endovascular approach is possible if the aortic measurements of these seal zones fit within the available device requirements (IFU). The outcomes are less acceptable if the anatomy does not allow for a good seal. The device is typically oversized at 10% to 20% at the aortic neck. The smallest aortic neck diameter can be treated is 16 mm, and the shortest neck length is 7 mm.

Angulation greater than 60 degrees is also a limiting factor for most devices; however, newer devices that address severely angulated neck anatomy, small access vessels, and concomitant iliac artery aneurysmal involvement are now available. Extensive calcium or mural thrombus at proximal or distal seal zones remains an issue for case planning. For aneurysmal disease extending up to or proximal to the renal and visceral arteries, newly approved devices and custom-designed grafts are available, allowing for a broader application of endovascular repair for these complex cases. The endovascular approach might be utilized in managing thoracoabdominal, pararenal, and juxtarenal aneurysms.[23]

Fenestrated and branched endovascular aneurysm repair applications in managing aortic aneurysms elucidated obvious advantages, including fewer perioperative complications, specifically significant in high-volume vascular centers. Stent graft selection and the durability characteristics of the stent determine the long-term efficacy of the fenestrated and branched endovascular aneurysm repair procedures. Fenestrated and branched endovascular aneurysm repair procedures are frequently reported together, and the separate effects of the procedures have not been discussed thoroughly. However, the surgeon's preferences mainly affect the selection of a balloon-expandable or self-expandable stent graft.[24]

Institutional algorithms for juxtarenal aortic aneurysm repair have addressed the factors affecting decision-making for the fenestrated and branched endovascular aneurysm repair procedures. However, there is a lack of absolute indications or contraindications criteria in the patient selection.[25] Accordingly, high surgical risk and appropriate morphology would greatly affect the decision-making towards the fenestrated endovascular repair. The aneurysm morphology characteristics to be reviewed include the localization of visceral and renal arteries, number of arteries, iliac access, and shaggy aorta.[25]

Considering the complications with fenestrated endovascular graft and fenestration stent repair, in-stent stenosis of bare metal renal stents is considered the most common indication for secondary intervention. The low rate of type IA endoleak, sac enlargement, and device migration favors fenestrated endovascular repair in patients with juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms.[26]

Guidelines on Management of abdominal aortic aneurysms

Updated guidelines on the care of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms were issued by the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) in 2018.[17] More recent guidelines were published in 2024 by the ESVS.[16] Select recommendations from these guidelines include the following:

- Yearly surveillance imaging is recommended for patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm diameter ranging from 4.0 to 4.9 cm.

- A preoperative 12-lead electrocardiogram is recommended for all patients undergoing endovascular aneurysm repair or open surgical repair within 4 weeks of the elective surgery.

- If the patient has recently undergone placement of a drug-eluting stent, open aneurysm surgery should be delayed for at least 6 months or endovascular surgery can be performed while the patient is still on dual antiplatelet therapy.

- Advise smoking cessation for at least 2 weeks before AAA repair.

- Consider transfusion of packer red blood cells perioperatively if the hemoglobin level is less than 7 g/dL.

- Elective repair should be recommended for low-risk male patients when the abdominal aortic aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm in diameter and 5-5.4 cm in maximal diameter in women.

- If the patient has suitable anatomy and reasonable life expectancy, endovascular aneurysm repair is the preferred modality for unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair.

- For a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, a facility with a door-to-intervention time of less than 90 minutes is preferred.

- For perioperative pain management, a multimodal approach is recommended, including consideration of epidural analgesia for postoperative pain after open AAA repair.

- Assessment of distal leg pulses at each postoperative clinic visit to monitor the patency of the graft limbs is recommended.

- Color duplex ultrasonography may be used for postoperative surveillance after endovascular surgery if it provides suitable imaging; otherwise, CT scan can be used.

- Treatment of types I and III endoleaks and type II endoleaks with aneurysm expansion are recommended.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended to prevent aortic graft infection before any dental procedure that involves manipulating the gingival or periapical region of the teeth or perforating the oral mucosa.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent aortic graft infection is recommended in immunocompromised individuals or those at risk for infection before respiratory tract, genitourinary, dermatologic, gastrointestinal, or orthopedic procedures.

- The endovascular procedure should only be performed in a hospital that conducts at least 10 cases yearly and has a conversion rate to open repair of less than 2%.

- Elective abdominal aortic aneurysm open surgery should be performed in hospitals with a mortality of less than 5% and at least 10 open cases conducted annually.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for abdominal aortic aneurysm includes mesenteric ischemia, peptic ulcer disease, diverticulitis, pyelonephritis, myocardial infarction, and ureteric colic.[27]

Prognosis

Once an abdominal aortic aneurysm ruptures, the prognosis is grim. More than 50% of patients succumb before they reach the emergency room, and those who do survive have very high morbidity. Predictors of mortality include preoperative cardiac arrest, age older than 80, female sex, massive blood loss, and ongoing transfusion.[28] In a patient with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, the one factor determining mortality is the ability to achieve proximal control. For those undergoing elective repair, the prognosis is good to excellent. However, long-term survival depends on other comorbidities such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, and peripheral vascular disease. An estimated 70% of patients survive for 5 years after repair.

Complications

The early complications associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm repair include bleeding, limb ischemia, abdominal compartment syndrome, myocardial infarction, pneumonia, ischemic colitis, renal failure, blue toe syndrome, amputation, lymphocele, and death. Close monitoring in the oerioerativve period is important and should include monitoring for arterial perfusion of the extremities, renal function testing, cardiovacular and pulmonary status. One postoperative event which may occur after either the open AAA repair or endovascular repair is ischemic colitis. This is related to interrupted perfusion of the inferior mesenteric artery or hypogastric artery which can occur in either repair although rare in EVAR AAA at less than 1%.[17]

The patient may present with a bloody bowel movement or abdominal pain. Supportive measures should be initiated including hydration ad bowel rest. Diagnosis with sigmoidoscopy and if confirmed, antibiotics should be administered. In severe cases, including full-thickness necrosis, colectomy should be performed. Other complications which usually present later include delayed rupture secondary to endoleak, graft infection, bowel obstruction, and impotence.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

After repair, it is essential that the patient discontinues smoking, eats a healthy diet, and maintains a healthy weight. Physical or occupational therapy may be necessary. Follow-up CT imaging 5 years after open repair management is recommended to exclude late aortic dilation or pseudoaneurysm.

Consultations

Once an abdominal aortic aneurysm is diagnosed, the patient should be referred to a vascular surgeon. Surveillance imaging at 12-month intervals is recommended for patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm diameter ranging from 4.0 to 4.9 cm.[17] As indicated, cardiology and pulmonary evaluations are recommended to ensure that the patient is fit for surgery.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Many patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms can lead healthy, symptom-free lives. The decision to undergo surgery involves weighing the risk of aneurysmal rupture against the risks and benefits associated with the surgical procedure. Although the size of the aneurysm and its enlargement rate are included in some general guidelines, each treatment decision should be made individually. Clinicians should discuss the surgical risks with their patients so they can make informed decisions.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key insights and recommendations concerning the management of abdominal aortic aneurysms are provided below.

- Patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms should quit smoking to reduce the risk of enlargement.

- Assessment of medical optimization of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and other atherosclerotic should be performed.

- Moderate exercise does not cause a rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion.[29]

- The SVS guidelines recommend ultrasound screening for all men and women aged 65 or older who have smoked or have a family history of abdominal aortic aneurysm.[30]

- Surveillance guidelines for abdominal aortic aneurysm per the SVS using duplex ultrasonography are the following:

- 3-year intervals for patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm diameter ranging between 3.0 and 3.9 cm

- 12-month intervals for patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm diameter ranging from 4.0 to 4.9 cm

- 6-month intervals for patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm diameter ranging between 5.0 and 5.4 cm

- Patients with an initial aortic diameter <3 cm have a low risk of rupture. At this time, there are no recommendations for surveillance; however, it should be noted that gradual expansion has been observed in these patients over time.

- Patients presenting with symptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm should be considered for urgent repair.

- Asymptomatic individuals with abdominal aortic aneurysm demonstrating an aortic diameter >5.4 cm or those with the rapid expansion of small abdominal aortic aneurysm should be evaluated for repair.

- The objective of abdominal aortic aneurysm repair is to increase survival rates. Consideration of the quality of life after the repair is essential, particularly in those with a shortened life expectancy due to medical comorbidities or cancer.

- Endovascular repair may offer fewer complications and a better quality of life in those at high risk for open repair up to 1-year after intervention.[31]

The factors that increase the operative risk for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair include severe heart disease, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, poor renal function, and comorbidities such as stroke, diabetes, hypertension, and advanced age, which can increase the risk of open surgical procedures. If the aortic anatomy permits, these individuals should be considered for endovascular aneurysm stenting.

Infrarenal Aortic Aneurysm Repair

Consideration for repair is appropriate for all symptomatic aneurysms. Aortic anatomy and device availability can dictate the approach. Open aneurysm repair had been the gold standard but carried increased risk and potential complications, which may be acceptable in a younger, good surgical-risk patient. This is still a more durable procedure.

Endovascular repair is now an established technique for repairing an abdominal aortic aneurysm. This minimally invasive procedure can also be offered but has better outcomes and durability when the anatomy meets device-specific recommendations. This is the preferred approach in rupture cases and patients with multiple risk factors or a shortened life expectancy. Intervention or surgical treatment risks versus benefits of repair in patients at an increased risk for open surgery should be considered, and no intervention may be appropriate in some cases.

Patients should be well-informed regarding their options, risks of repair, and potential postoperative complications. Endovascular repair requires lifelong follow-up with imaging as early or late endoleaks may develop, causing aortic sac pressurization and rupture. Secondary interventions, most of which are minimally invasive, may be necessary. Still, there is a small chance that an open conversation with the stent-graft removal may be required when these secondary endovascular interventions fail.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms are the most common aneurysms of the aorta. Screening ultrasound has helped in the detection of abdominal aortic aneurysms and allows for surveillance in asymptomatic individuals with a diameter of less than 5 cm. In women, the repair should be considered at 5 cm, and in men, at 5.5 cm. If rapid enlargement is demonstrated (>5 mm over 6 months), repair should be considered. Educating healthcare professionals, including first responders, nurse practitioners, triage nurses, primary care clinicians, physician assistants, and emergency department clinicians, can facilitate diagnosis and reduce delays in treatment.

An interprofessional team approach involving clinicians including emergency nurses and clinicians, intensivists, radiologists, and vascular surgeons will facilitate rapid evaluation and treatment and improve outcomes. Most patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm initially present to the emergency department with vague abdominal pain or a pulsatile mass. Thus, the triage nurse must be familiar with the presentation of an abdominal aortic aneurysm and initiate a rapid admission with direct communication to the emergency department clinician and the full interprofessional team about the patient. Once admitted, if stable, these patients require an urgent ultrasound; therefore, the radiologist should be notified. If the patient is unstable, the nurse should obtain vital signs, attach monitoring equipment, and assist with resuscitation if the patient is hemodynamically unstable.

Referral to a vascular center capable of providing a standard-of-care management is appropriate. Once the decision for repair has been made, conducting a cardiology workup, obtaining clearance, and optimizing other medical comorbidities can improve outcomes. If the aneurysm is small, the interprofessional team should educate the patient and family about the importance of blood pressure control, a healthy diet, regular exercise, smoking cessation, and follow-up appointment adherence.

During postoperative care, the nurse must be familiar with potential complications of the surgery and notify the interprofessional team if the patient has abdominal or back pain, wound discharge, fever, oliguria, or hypotension. The nurse should also ensure the patient has prophylaxis to prevent deep vein thrombosis. The respiratory therapist should encourage deep breathing and coughing, and the physical therapist should encourage ambulation. The nurse should also auscultate for bowel sounds and convey the results to the interprofessional team to initiate feeding. Before discharge, the pharmacist and nurse should educate the patient on the importance of medication compliance, blood pressure control, and tobacco avoidance. The nurse should also ensure that the appropriate consulting clinician, dietitian, or social workers have spoken to the patient and that the surgeon has been notified before discharge. Open communication among the interprofessional team is vital to ensure good outcomes.

Outcomes

For elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, the outcomes are good, with minimal morbidity. However, if a rupture has occurred, the mortality rates can exceed 50%. Current guidelines suggest that patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm should undergo surgery in hospitals with an interprofessional team approach to manage this pathology. To improve outcomes, it is imperative that patients stop smoking, maintain a healthy body weight, control their blood pressure, and remain compliant with medications.