Continuing Education Activity

Acetabular fractures primarily occur in young people who are involved in high-velocity trauma. Since the advent of mandatory seatbelt use, there has been a significant reduction of acetabular fractures to approximately an incidence of 3 per 100000. There has been an increase in the number of acetabulum fractures resulting from a fall of fewer than 10 feet, likely due to the increase in osteopenia/osteoporosis. Little has changed since Letournel and Judet’s landmark paper in 1993, and many of their findings remain the “gold standard” for treatment today. Among the most significant advancements has been the advent of percutaneous fixation of certain fracture types. This activity outlines the evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with acetabulum fractures. It also reviews the role of pre, peri, and post-operative management of acetabulum fractures.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology and epidemiology of acetabulum fractures.

- Describe the evaluation of acetabulum fractures.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for acetabulum fractures.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance acetabulum fractures and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Acetabular fractures primarily occur in young people who are involved in high-velocity trauma. Since the advent of mandatory seatbelt use, there has been a significant reduction of acetabular fractures to an approximate incidence of 3 per 100000. There has been an increase in the number of acetabulum fractures resulting from a fall of fewer than 10 feet, likely due to the rise in osteopenia/osteoporosis.[1] Little has changed since Letournel and Judet’s landmark paper in 1993, and many of their findings remain the “gold standard” for treatment today. Among the most significant advancements has been the advent of percutaneous fixation of certain fracture types.

Anatomy

The innominate bone forms from the pubis, ischium, and ilium at the triradiate cartilage. The superior portion of the acetabulum articular surface has the name of the weight-bearing dome. Blood supply to the external surface is via the superior gluteal artery, inferior gluteal artery, obturator artery, and medial femoral circumflex. Blood supply to the internal surface comes from the fourth lumbar, iliolumbar, and obturator arteries. One can visualize the articular surface as an inverted Y with a thick strut of bone connecting it to the sacroiliac (SI) joint, known as the sciatic buttress. The acetabulum divides into an anterior and posterior column. The anterior column contains the anterior half of the iliac wing that is contiguous with a pelvic brim to superior pubic ramus and anterior half of the acetabular articular surface. The posterior column begins at the superior aspect of the greater sciatic notch, contiguous with greater and lesser sciatic notches, and includes the ischial tuberosity.

Etiology

Acetabular fractures are often high energy and therefore often present in combination with other organ injuries. These fractures have very high morbidity because the damage to the cartilage can lead to disabling osteoarthritis in the future. In large series reported by Matta, 50% of patients had associated injuries: 35% with extremity injury, most commonly lower extremity, 19% with a head injury, 18% with a chest injury, 13% with nerve palsy, 8% abdominal injury, 6% genitourinary, and 4% spine.[2] Even isolated fractures of the acetabulum require blood transfusion; high as 35% in one study.[3] Injury to the sciatic nerve also must be evaluated upon admission. When a sciatic nerve injury occurs, it almost always involves the peroneal division of the nerve and less commonly also involves the tibial division. Injury to the peroneal nerve division of the sciatic nerve will result in a foot drop.[4]

Epidemiology

These are commonly a result of high-speed car crashes, falls from heights, and extreme sporting events. As mentioned above, the incidence over the past couple of decades has remained stable at 3 per 100000 people per year. The number of fractures caused by motor vehicle accidents has remained similar, but the number from falls from less than 10 feet has increased. There has also been an increase in the average age in patients with acetabulum fractures.[5]

Pathophysiology

Fractures of the acetabulum occur by the impact of the femoral head on the articular surface.[6] The pattern depends on the position of the hip at the time of impact; external rotation will result in anterior fracture patterns, and internal rotation will result in posterior fracture patterns. Falls on the greater trochanter will most likely result in an anterior column and/or wall fracture (elderly).

History and Physical

Initial assessment begins with following the standard principles of trauma assessment and resuscitation protocols. The mechanism of injury should be determined and can help guide treatment. Physical exam should include whole body evaluation for other signs of trauma/associated injuries. A complete review of the musculoskeletal system is required, especially of the peripheral nerves and skin. Soft tissue should undergo evaluation for the possibility of a Morel-Lavalle lesion.[7]

Evaluation

The diagnosis of acetabular fracture is possible just with a plain X-ray, but because many patients have multiple organ injuries, a CT scan is often necessary, which is more precise than a conventional X-ray. Plain films, with an AP pelvis and Judet views, are often obtained first. The Judet views include an obturator oblique and an iliac oblique view. There are six radiographic landmarks identifiable on an AP view of the pelvis and help classify the fracture pattern.[6] The landmarks are:

- Iliopectineal line

- Ilioischial line

- Teardrop

- Roof of acetabulum

- Anterior wall

- Posterior wall

The iliopectineal line represents the anterior column and is made up of the pelvic brim and sciatic buttress and greater sciatic notch. The ilioischial line represents the posterior column, which is a tangency of the quadrilateral surface. The teardrop represents a radiographic finding and is not a true anatomical structure. The lateral limb represents the inferior aspect of the anterior wall and the medial limb forms from the obturator canal and the anterior inferior portion of the quadrilateral surface. The advent of CT scans has made the diagnosis and classification of acetabulum fractures much easier. CT axial images are superior to plain radiographs in evaluating the following in acetabulum fractures: Extent and location of acetabular wall fractures, presence of intra-articular fragments, the orientation of fracture lines, the identification of additional fracture lines, rotation of fracture fragments, the status of posterior pelvic ring, and marginal impaction. 2D images are better used for evaluation of the fracture patterns, while 3D imaging may help less experienced surgeons.[8] Dynamic stress X-rays can also be obtained to evaluate for hip stability, usually when there is a fracture-dislocation involving the posterior wall. The patient is supine with the hip extended and in neutral rotation, then the hip is flexed to 90 degrees, and a manual force is applied while taking plain films. Any evidence of hip subluxation means hip instability.[9]

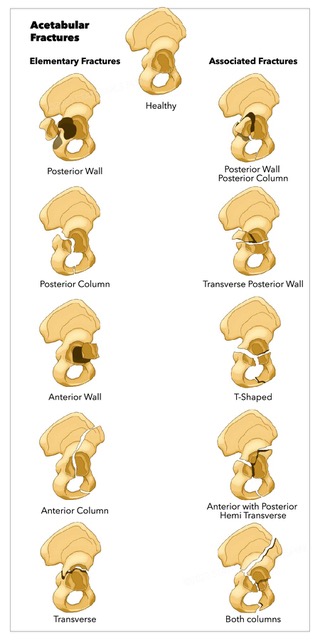

Classification

By far the most used and most useful classification for acetabulum fractures is that of Letournel.[10] This system divides fractures into five elementary types and five associated fracture patterns.

Elementary patterns:

- Posterior wall: Most common type (25%) and are visible on the AP and obturator oblique views

- Posterior column: Fracture begins at the apex of the greater sciatic notch, goes through the articular surface and quadrilateral surface, crosses inferior pubic ramus. (3 to 5%). The superior gluteal neurovascular bundle can become caught in the fracture site. On the AP: ilioischial line, posterior rim and inferior ramus show as disrupted. On the iliac oblique: fracture crosses the posterior border of the bone.

- Anterior wall: Fracture begins below the AIIS and ends at the ischiopubic notch. On AP imaging, will show the anterior wall and iliopectineal disruption

- Anterior column: This fracture separates the anterior border of the innominate bone from the intact ilium. It can be high, intermediate, low, or very low based on where the fracture exits the anterior aspect. The iliopectineal line becomes disrupted on the obturator oblique.

- Transverse: Fracture of both the anterior and posterior columns. See disruption of both the ilioischial and iliopectineal lines on AP view

Associated patterns:

- Posterior column and posterior wall: Femoral head frequently dislocated on presentation. Disruption of ilioischial line, posterior border of innominate bone, and posterior wall

- Transverse and posterior wall: Represents approximately 20% of acetabulum fractures. See large posterior wall fragment on obturator oblique view

- Anterior column/wall and posterior hemitransverse: Fracture of the column more common than of the wall. The primary fracture line is anterior, while the secondary fracture line through the articular surface to the posterior border. Gullwing sign is seen on the AP radiograph and represents the impaction of the acetabular roof on the superior medial side (poor prognosis).

- T-type: Transverse fracture plus an inferior vertical fracture line (stem of T). It can be associated with a posterior wall fracture, which has the worse prognosis of any subgroup. Radiographs show a transverse fracture with a fracture of the inferior pubic rami.

- Both columns: This is the most commonly associated type. Represents an acetabulum that has completely disconnected from the axial skeleton. It can have secondary congruency, which is when the femoral head medializes but the articular fragments rotate and remain congruent to femoral head due to the attachment of the labrum. Spug sign is pathognomonic, which is seen on the obturator oblique and represents the intact portion of the ilium.

Treatment / Management

The majority of acetabular fractures require open reduction and internal fixation. Indications for non-operative treatment include[11]:

- All stable, concentrically reduced fractures not involving the superior acetabular dome

- Fractures in which the intact part of the acetabulum is large enough to maintain stability and congruency, and those with secondary congruency

- Roof arc measurement: greater than 45 degrees on AP, iliac oblique, obturator oblique

- Low anterior column, low transverse, low T shaped

- Both column with secondary congruence (no traction)

Evaluation of the vertex (the most superior portion of the roof) on CT scan can help identify fractures that are amenable to non-operative management. Evaluation involves scanning from the vertex to 10mm inferiorly. If the CT scan shows no fracture lines involving this area, the fracture can be a candidate for non-operative management; displacement cannot exceed 2 mm.[11]

Fractures treated non-operatively require bed rest initially for comfort. Once pain allows, immobilization should follow. Begin with foot-flat partial weight bearing (<10kg); radiographs obtained weekly for the first 4 weeks. Progress to full weight bearing by 6 to 12 weeks (once adequate fracture healing). Prolonged traction (4 to 12 weeks) if fracture indicates surgery, but the patient is not a surgical candidate.

Indications for ORIF include all fracture patterns that result in hip joint instability of incongruity, bone/soft tissue incarcerated within the joint, or in situations in which non-operative treatment is not a satisfactory option, total hip arthroplasty of percutaneous fixation should be a considered approach.

Percutaneous fixation is gaining popularity, especially as an adjunct to ORIF, or in sicker patient’s or where extensive approaches not suitable[12][13]:

- The patient is supine or lateral, c-arm on the same side as the fracture

- Post. Column: leg held with the hip/knee flexed, leg in slight external rotation, palpate ischial tuberosity. The guidewire is placed in the center of tuberosity and drilled up PC. Frequent iliac and obturator obliques need to be taken to guide wire placement

- Anterior Column: C-arm rotated to show an inlet-iliac oblique view and an outlet-obturator oblique view; For antegrade, a starting point between the tip of the greater trochanter and thick part of the iliac crest (usually 4 to 5 cm back from ASIS). Then the wire placed into superior ramus; for retrograde, pin placement is against pubic tubercle through mini-Pfannenstiel; aimed just posterior and inferior to AIIS, and wire is passed through superior ramus

Timing for ORIF is usually 3 to 5 days after injury; delays over 3 weeks associated with poorer outcomes.[14] Indications for emergency surgery: Recurrent hip dislocation despite traction, irreducible hip dislocation, progressive sciatic nerve deficit, vascular injury, open fractures, ipsilateral femoral neck fractures.

Selection of Approach[10]

- Based on fracture type, the elapsed time from injury, and magnitude and location of maximal fracture displacement

- Mainstay approaches are: Kocher-Lagenbeck (KL), ilioinguinal, iliofemoral (IF), and extended iliofemoral

- KL is used for the posterior column, II and IF for the anterior column; rely on indirect manipulation for reduction of any fracture that transverses opposite column; the second approach used if an unsatisfactory reduction

- Extended IF affords access to all aspects of acetabulum; most often used for delayed treatment

Reduction and Fixation

- Except for both column fractures, standard fracture reduction sequence is first to reduce and stabilize displaced column fractures and then reduce any wall fracture

- After definitive fixation of reduced fragments, entire construct stabilized with buttress plates

- For both column fractures, first reduce and stabilize one of the columns to the axial skeleton (iliac wing), then the other column, and later, if present, the wall component. The entire construct then gets stabilized with buttress plates

- Columns may be stabilized in young, healthy bone using screws alone; osteopenic bone and all wall fractures require buttress plating

Differential Diagnosis

In general, one should not confuse acetabulum fractures with other fracture types given the advent of CT scans. Other fracture patterns on the differential include fracture of the pelvic ring and fractures of the proximal femur. In elderly patients that sustain low energy falls with fractures, one must be judicious about ruling out a pathologic fracture.

Prognosis

The prognosis of acetabulum fractures has generally been poor due to the high energy and multiple associated injuries. However, with the advent of open reduction and internal fixation, the prognosis is generally regarded as good. The prognosis has its basis on several factors, including fracture pattern (T-type with the worst prognosis), condition of the hip at the time of injury (femoral head lesions, marginal impaction, gull sign, adequacy of hip reduction, the stability of joint after treatment). The clinical and radiographic findings at one year are the most reliable guide to prognosis after treatment, as most hips do not improve after this time.

Complications

The following complications can occur with acetabular fractures[15][16][17]:

- Post-traumatic arthritis and osteonecrosis; quality of reduction is the main determinant for risk of late arthritis and goal should be a reduction within 1 mm

- Infection (approx 5%)

- Iatrogenic nerve injury

- DVT(4% symptomatic DVT, 1% PE)

- Intra-articular hardware

- Heterotopic ossification (extended IF more than KL more than ilioinguinal)

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients in skeletal traction before the procedure have changes in skin flora because they cannot cleanse perineum; therefore, prophylactic antibiotics should include a first-generation cephalosporin and often supplemented with gram-negative coverage. Drains are often used for 48 hours or until drainage has ceased.

High Risk for DVT

- Mechanical SCDs to both legs upon admission until discharge

- Chemical prophylaxis until ambulatory (6 to 12 weeks)

Heterotopic ossification prophylaxis is for extended or posterior approaches. Heterotopic ossification prophylaxis includes an irradiation-single dose of 700 to 800 cGy delivered within 72 hours after surgery or indomethacin 25 mg three times daily beginning within 24 hours after surgery and continued for 6 weeks-contraindicated for long bone fractures at risk of nonunion.[17] The patient is usually toe-touch or flat foot weight-bearing to the affected extremity for 2 to 3 months following surgery, then allowed to weight bear as tolerated. Physical therapy is generally initiated on postoperative day one.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence of acetabulum fractures is often unavoidable; however, patients driving motor vehicles should always wear a seatbelt. Elderly patients should have screening for osteopenia/osteoporosis and DEXA scans, Vitamin D/bisphosphonates, and trip precautions can be used to help avoid fragility fractures and falls.

Pearls and Other Issues

Acetabular fractures should not be treated lightly, and patients require aggressive hydration, fluid monitoring, and even blood transfusions. The pain can be significant. After surgery, prolonged rehabilitation is necessary to regain balance and strength.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing acetabulum fractures requires an interprofessional team approach, including physical therapists and orthopedic nurses. The emergency department and trauma services should recognize acetabulum fractures in trauma patients and be aware of the associated conditions and morbidity/mortality associated with these fractures. Stabilization by the trauma services for early surgery (3 to 5 days) improves patient outcomes. It is vital that all teams involved in the management of patients with acetabulum fractures are aware of the severity of these injuries.

Acetabular fracture treatment and management/rehabilitation require an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, physical and occupational therapists, and pharmacists, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. [Level V]