Continuing Education Activity

Airway obstruction secondary to a foreign body is often easily treated, as the foreign body can be removed, and the patency of the airway restored. However, airway obstruction caused by trauma, malignancy, or an infectious process may lead to delayed recovery and hypoxic brain damage. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of airway obstruction and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the recognition and management of this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the pathophysiologic basis of airway obstruction.

- Outline the expected history and physical findings for a patient with airway obstruction.

- List the treatment options available for airway obstruction.

- Review the need for an interprofessional team approach to caring for a patient with airway obstruction.

Introduction

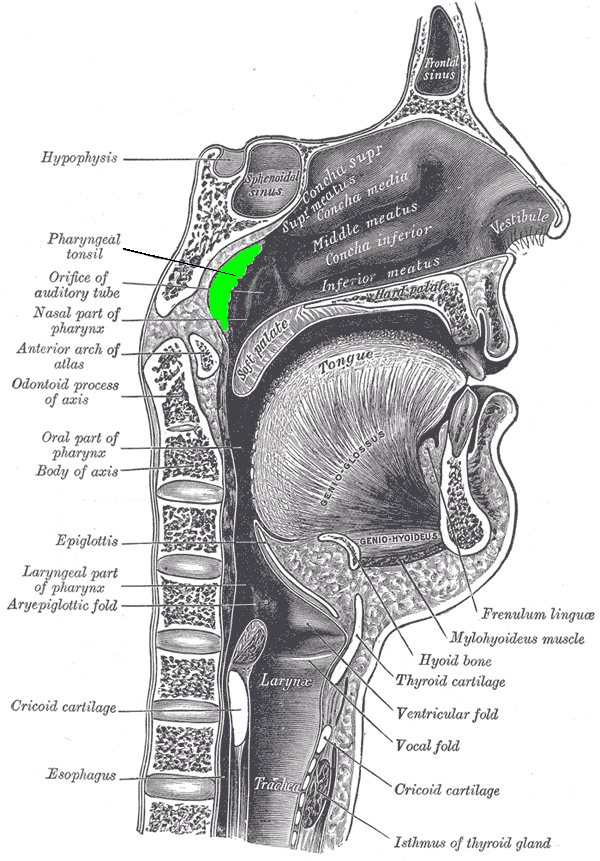

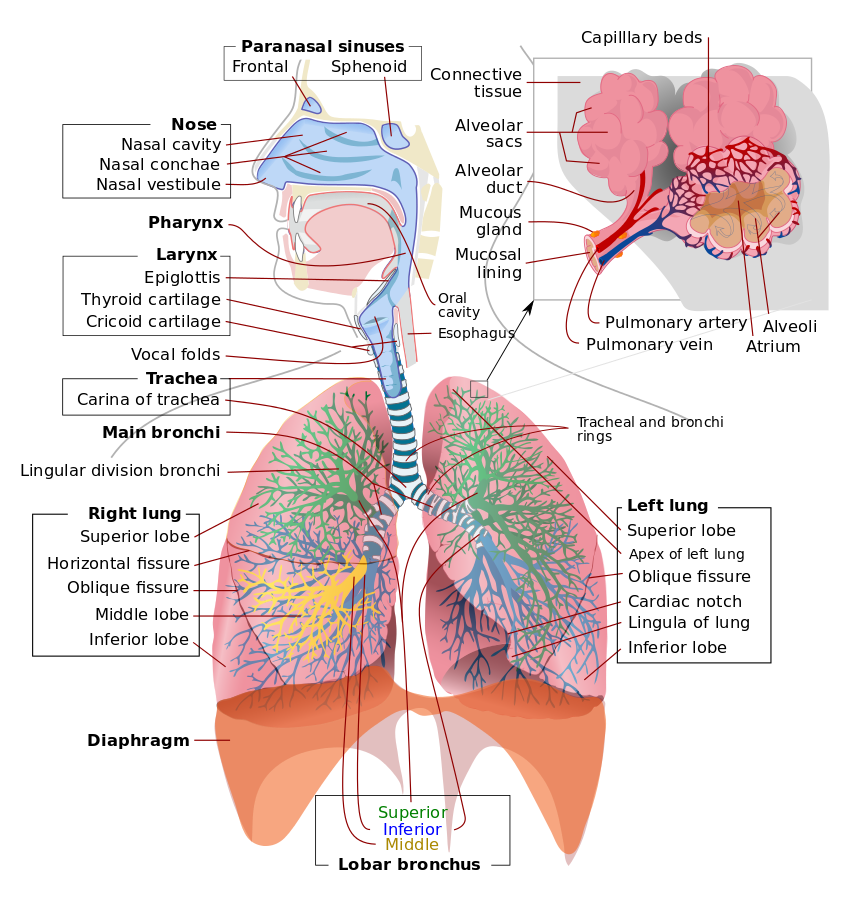

Upper airway obstruction refers to an anatomic narrowing or occlusion, resulting in a decreased ability to move air (ventilate). Upper airway obstruction may be acute or chronic. Upper airway obstruction may also be partial or complete, with complete obstruction indicating a total inability to get air in or out of the lungs. Often partial and complete acute causes of airway obstruction require emergency intervention, or they may be fatal. This is because acute obstruction causes a decreased ability to ventilate, which can be fatal in a matter of minutes. Chronic airway obstruction may produce a cardiopulmonary compromise that may eventually also lead to morbidity or death. The upper airway may be acutely or chronically obstructed by nasal and oral pharyngeal pathology. The anatomical area where the resistance to air is highest is the nasal valve, and even mild deviation in this area can lead to significant upper airway obstruction.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Any pathology that compromises airflow from the nasopharynx and oropharynx to the lungs can cause upper airway obstruction. Often, etiologies that cause upper airway obstruction involve inflammation, infection, or trauma of the airway structures. An anatomic variant may also cause or contribute to obstruction. Causes of airway obstruction include deviated septum, foreign body ingestion, macroglossia, tracheal webs, tracheal atresia, retropharyngeal abscess, peritonsillar abscess, rhinitis, polyps, enlarged tonsils, lipoma of the neck, nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal cancers, edema from epiglottitis, blunt or penetrating trauma, anaphylaxis, turbinate hypertrophy, and chemical or thermal burns. Obstructive sleep apnea is a medical condition that is a subset of sleep apnea and is considered a chronic cause of airway obstruction.[4]

Epidemiology

Most children who die from airway obstruction injuries are usually younger than four years of age. In adults, airway obstruction is more common with inflammation, infection, and trauma. Airway obstruction is a common cause of emergency department visits.[4]

History and Physical

In cases of acute obstruction of the airway, a history of the events leading to the obstruction may be critical to deciding the intervention necessary to alleviate the potentially life-threatening symptoms. Often, secondary to the obstruction, the patient may be unable to give this history, and health care providers may have to rely on family or bystanders for pertinent history. Making a diagnosis of airway obstruction requires a thorough exam of the head and neck. Patients with acute obstruction, such as foreign body ingestion, trauma, or anaphylaxis, provide an acute challenge to the healthcare provider because these often require rapid diagnosis and intervention. These patients often present with acute distress, altered mentation, and other signs of inability to move air. Patients may also present in an obtunded state or cardiopulmonary arrest. The physical exam should be focused on finding correctable sources of obstruction, especially in patients in acute distress. Nasal passages should be inspected, as well as the oropharynx. The neck should be examined entirely for pathology that may be causing external compression on airway structures. Patients with obstructive sleep apnea may present with obesity and a wide and short neck. Often the tongue may be large, and the mandible may be small. Adjuncts to the physical exam include nasal speculum with a light source, rigid or flexible endoscopy, and direct laryngoscopy.

Evaluation

In cases of acute upper airway obstruction, evaluation should be prompt, and the provider should be prepared to proceed to intervention with limited delay. All necessary airway equipment should be made available at the time of evaluation in case immediate intervention is required. The nasopharyngeal area may be evaluated with a flexible or rigid endoscope. Direct laryngoscopy is another tool that may also be helpful not only for diagnosis but also in case of intervention. Imaging techniques are available, but extreme caution should be utilized in patients with an acute obstruction or chronic obstruction with acute distress. Obtaining imaging should not delay the correction of obstruction in patients in acute distress. In these cases, imaging may be helpful in determining etiology after the obstruction has been alleviated. Imaging modalities that are used to assess airway obstruction include the lateral head and neck x-rays, CT scans, and MRI. CT scans produce images that can assess both bony structures and soft tissues. The airway diameter can be evaluated, as well. The latest CT scans are fast and can create three-dimensional images. Again caution must be undertaken when deciding if the patient is stable for such diagnostic testing. MRI can also be quite helpful in determining the etiology of airway obstruction. MRI is of particular benefit when evaluating soft tissue masses and surrounding structures. Besides generating three-dimensional images, MRI does not produce radiation, and dye is not always used. The limitations of MRI are availability and cost.[5][6]

Treatment / Management

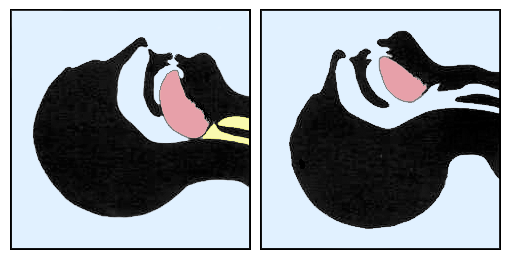

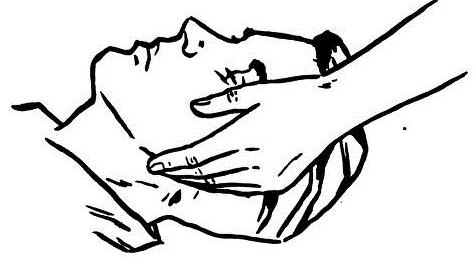

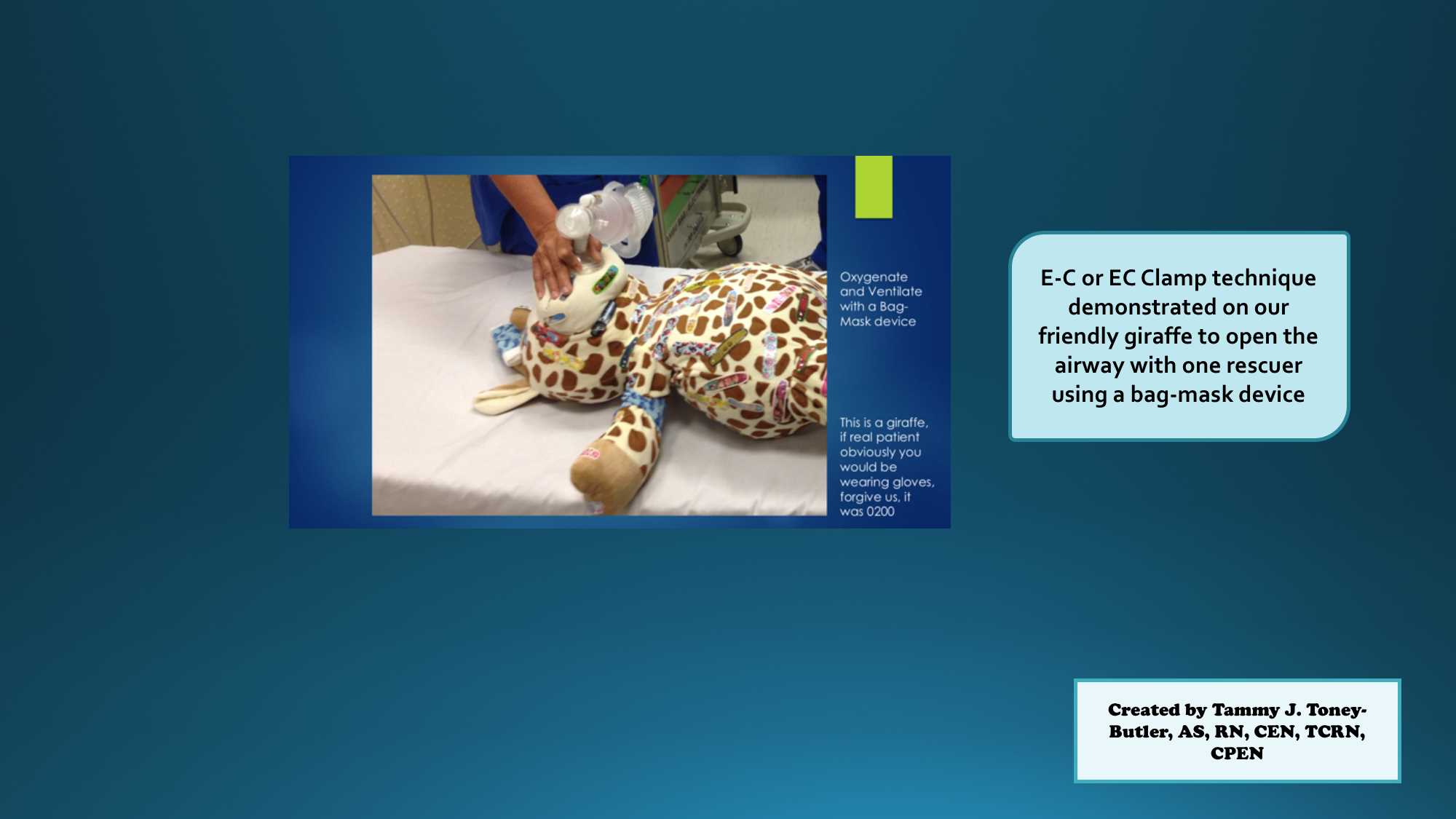

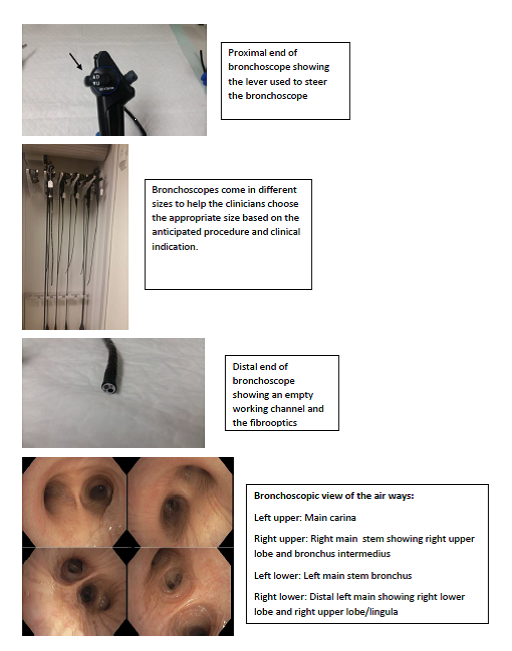

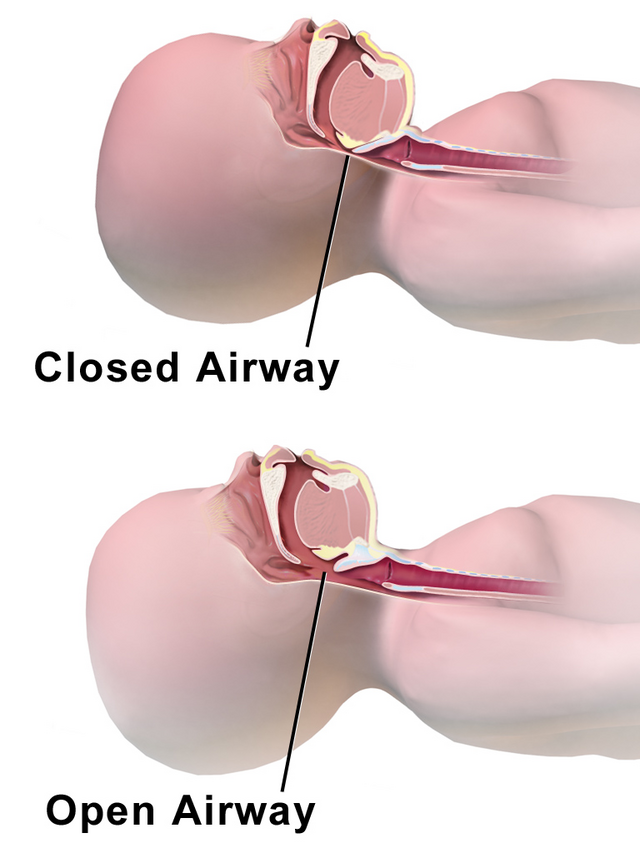

The immediate goal in the management of patients with airway obstruction is relieving the obstruction, so air exchange (oxygenation and ventilation) can proceed. In an acute obstruction of the airway, this may be critical because if left uncorrected, obstruction is often fatal in a matter of minutes. Correction of airway obstruction may be achieved by correcting the underlying pathology, but also may require intervention that alleviates the obstruction without correcting the underlying pathology, especially in urgent cases. When preparing to treat a patient with potential acute airway obstruction, all anticipated equipment and personnel should be available as soon as possible. This includes airway supplies for nasotracheal and endotracheal intubation, as well as, surgical airway equipment. Experts in airway management should be sought out as available. These may include anesthesia providers, emergency medicine providers, respiratory therapists, and critical care providers. Surgical consultation for possible surgical airway should be considered before the need for surgical airway arises. Additional equipment that might be of benefit in a difficult airway situation such as a bronchoscope should also be obtained as soon as possible. Supplemental oxygen should be provided to the patient and attempts to reposition the patient, such as a chin lift and jaw thrust maneuver, should be undertaken. Cervical spine precautions should be observed in patients believed to be involved in trauma leading to their airway compromise. Immediate and definitive relief of obstruction may include removal of foreign body, nasotracheal intubation, endotracheal intubation, tracheostomy, or cricothyroidotomy. Additional procedures such as jet insufflation may provide temporary relief. Efforts to treat the underlying cause of the obstruction should also be considered. In cases of infectious etiology, these should be treated with appropriate antibiotics and surgical drainage when indicated. In the case of obstructing masses, these may be worked up after the airway is secured, and proper surgical consultation should be obtained. In more chronic causes such as obstructive sleep apnea, diagnostic studies should be performed, and patients may require intervention while sleeping and possible surgery.[7][8]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of acute upper airway obstruction:

- Aspiration

- Infection

- Hemorrhage

- Angioedema

- Iatrogenic (e.g., post-surgical, instrumental)

- Blunt trauma

- Inhalation injury

- Neuromuscular disease

The differential diagnosis of chronic airway obstruction:

- Infection

- Post-intubation

- Amyloidosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Tumor

- Collagen vascular disease

- Mediastinal mass

- Esophageal tumor

- Cardiovascular anomaly

- Neuromuscular disease

- Idiopathic

- Tonsillar enlargement in children

Prognosis

The prognosis of airway obstruction depends on the etiology of the condition. Generally, the prognosis of inflammatory and infectious causes is more favorable than that of malignancy.

Complications

The complications of airway obstruction are:

- Respiratory failure

- Arrhythmias

- Cardiac arrest

- Death

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Airway obstruction can occur both in the hospital and at home. Thus, all healthcare workers must know how to manage this life-threatening emergency. Because death can occur within minutes, an interprofessional team approach is necessary to save the life of the patient. All healthcare workers who look after patients should be familiar with the signs and symptoms of respiratory distress. Most hospitals now have a team of professionals who are in charge of intubation outside the operating room. In most cases, it is the nurse who first identifies the patient with respiratory distress and alerts the rest of the team.

The nurse is usually the one person who knows where the equipment to manage this emergency is kept and should have it available. Once the team has arrived, the key is to establish an open airway quickly, and this may be done by removing the foreign body, performing inhalation induction, or an awake tracheostomy.

Both the anesthesiologist and surgeon should be notified when a patient has an airway obstruction. The nurse anesthetist should be dedicated to the monitoring of the patient while the clinicians are attempting to intubate the patient. If orotracheal intubation fails, then a surgical airway is required.

Performing an emergency tracheostomy in the emergency department or at the bedside requires a great deal of skill and knowledge of the neck anatomy; it should not be attempted by anyone who has never done a formal tracheostomy in the operating room. Irrespective of how a patent airway is obtained, the patient does need monitoring in the ICU overnight. ICU nurses should be familiar with monitoring of intubated patients and communicate with the team if there are issues with oxygenation or ventilation

Some patients may require PEEP and corticosteroids to reduce the swelling from traumatic intubation. Imaging studies, arterial blood gas, and a clinical exam are needed frequently during admission. [9][10]

Outcomes

The outcomes for patients with airway obstruction depend on the cause. If the cause is a foreign body that has been removed, the outcomes are excellent. Airway obstruction caused by trauma, malignancy, or an infectious process may lead to delayed recovery and hypoxic brain damage. In some cases, deaths have been reported. The longer it takes to achieve a patent airway, the greater the risk that the patient may suffer from anoxic brain damage or even a cardiac arrest.[2][11][12]