Continuing Education Activity

This Continuing Medical Education (CME) activity provides healthcare professionals with the latest updates and evidence-based practices for diagnosing and managing Alzheimer's disease, a progressive neurodegenerative disorder affecting millions worldwide. Through a comprehensive and interprofessional approach, participants will gain valuable insights into the clinical features, biomarkers, and neuroimaging for early detection, as well as pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to support cognitive function and improve patient care. The activity also addresses the coordination of interprofessional teams, patient education, and emerging disease-modifying therapies.

Objectives:

Identify early signs and symptoms of Alzheimer disease in patients, including memory impairment, cognitive decline, and behavioral changes.

Implement evidence-based treatment approaches, including pharmacological therapies and non-pharmacological interventions, to manage cognitive and behavioral symptoms.

Select appropriate resources and educational materials to empower patients and caregivers with accurate information about Alzheimer disease and its management.

Collaborate with other healthcare professionals and community resources to provide comprehensive care and support for Alzheimer disease patients throughout the disease trajectory.

Introduction

Dementia is a general term used to describe a significant decline in cognitive ability that interferes with a person's activities of daily living. Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most prevalent type of dementia, accounting for at least two-thirds of cases in individuals aged 65 and older. AD is a neurodegenerative condition with insidious onset and progressive impairment of behavioral and cognitive functions. These functions include memory, comprehension, language, attention, reasoning, and judgment. While AD does not directly cause death, it substantially raises vulnerability to other complications, which can eventually lead to a person's death.

According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data, AD is ranked as the seventh leading cause of death in the United States in 2022, while COVID-19 ranked fourth. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, AD was the sixth leading cause of death following stroke.[1]. AD typically manifests after age 65, referred to as late-onset AD (LOAD). However, early-onset AD (EOAD), occurring before 65, is less common and seen in about 5% of AD patients. EOAD often exhibits atypical symptoms, and its diagnosis is usually delayed, leading to a more aggressive disease course.[2]

Significant progress has been made in developing biomarkers for specific and early diagnosis of AD over the past decade. These biomarkers include neuroimaging markers obtained through amyloid and tau PET scans, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and plasma markers, such as amyloid, tau, and phospho-tau levels.[3]

There is no cure for AD, although there are treatments available that may alleviate and manage some of its symptoms. In recent years, there have been significant advancements in the development of medications that aim to moderate the progression of the disease, particularly with the discovery of new disease biomarkers.[3]

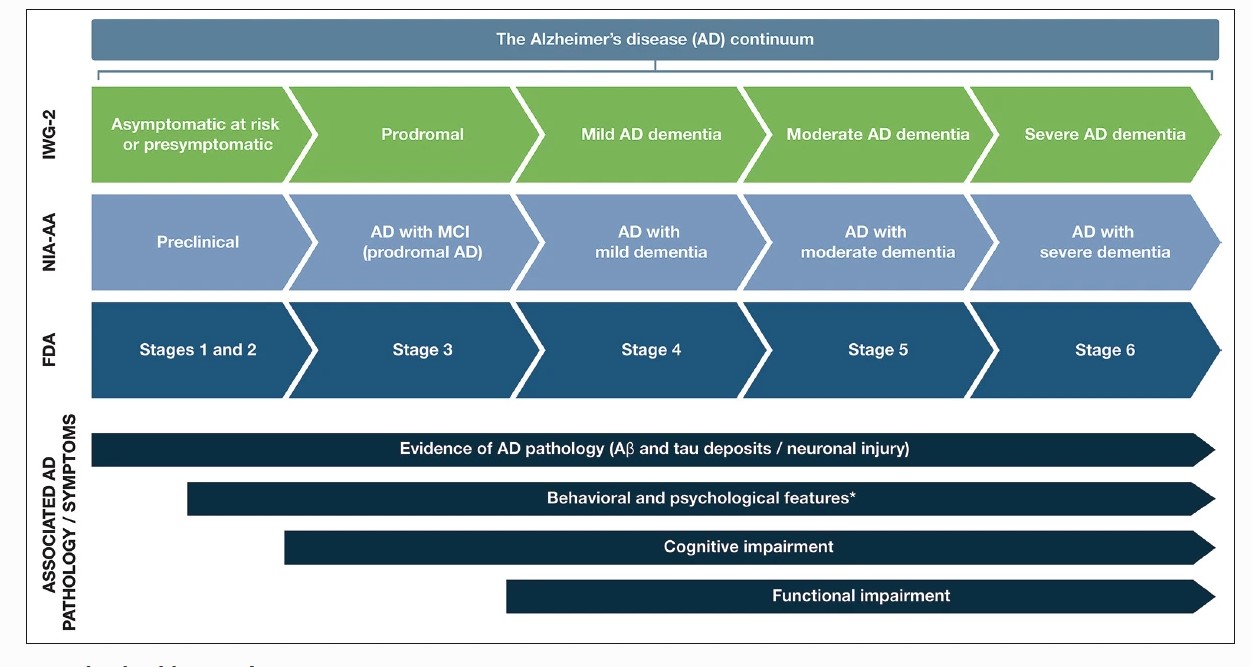

The symptoms of AD can vary depending on the stage of the disease. AD is classified into different stages based on the level of cognitive impairment and disability experienced by individuals. These stages include the preclinical or presymptomatic stage, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia stage. The dementia stage is further divided into mild, moderate, and severe stages (see Graph. AD Stages from Preclinical to Severe Disease).[4] This staging system is distinct from the diagnostic criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) for AD.[5]

Episodic short-term memory loss is the initial and most common presenting symptom of typical AD. Individuals may have difficulty retaining new information while still recalling long-term memories. Individuals may experience problem-solving, judgment, executive functioning, and organizational skills impairments following short-term memory loss.

They may struggle with tasks that require multitasking and abstract thinking. In the early stages of the disease, executive functioning impairments can range from subtle to significant. Instrumental activities of daily living such as driving, financial management, cooking, and detailed activity planning are affected relatively early in their dementia.

These early signs of cognitive decline are followed by language disorder and impaired visuospatial skills. Neuropsychiatric symptoms like apathy, social withdrawal, disinhibition, agitation, psychosis, and wandering are also common in the moderate to late stages. Difficulty performing learned motor tasks (dyspraxia), olfactory dysfunction, sleep disturbances, and extrapyramidal motor signs like dystonia, akathisia, and Parkinsonian symptoms occur late in the disease. Primitive reflexes, incontinence, and total dependence on caregivers follow this.[6][7][8]

Etiology

Alzheimer disease is characterized by gradual and progressive neurodegeneration caused by neuronal cell death. The neurodegenerative process typically begins in the entorhinal cortex within the hippocampus. Genetic factors have been identified to contribute to both early and late-onset AD. Trisomy 21, for example, is a risk factor associated with early-onset dementia.

AD is a multifactorial condition associated with many known risk factors. The most significant factor is age, with advancing age being the primary contributor. The prevalence of AD approximately doubles with every 5 years increase in age starting from age 65.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are recognized as significant risk factors for AD. They increase the risk of developing AD and contribute to the risk of dementia caused by strokes or vascular dementia. CVD is increasingly recognized as a modifiable risk factor for AD.[9]

Obesity and diabetes are also important modifiable risk factors for AD. Obesity can impair glucose tolerance and increase the risk of developing type II diabetes. Chronic hyperglycemia can lead to cognitive impairment by promoting the accumulation of beta-amyloid (A-beta) and neuroinflammation. Obesity further amplifies the risk by triggering the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and promoting insulin resistance.[10]

Other potential risk factors for AD include traumatic head injury, depression, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, higher parental age at birth, smoking, family history of dementia, increased homocysteine levels, and the presence of the APOE e4 allele. Having a first-degree relative with AD increases the risk of developing the disease by 10% to 30%. Individuals with 2 or more siblings with late-onset AD face a 3-fold higher risk than the general population.[11][12][13]

Several factors have been identified that may potentially reduce the risk of developing AD. These include higher education, estrogen use in women, anti-inflammatory agents, leisure activities such as reading or playing musical instruments, maintaining a healthy diet, and regular aerobic exercise.

Epidemiology

AD is predominantly observed in older individuals. The global prevalence of dementia was reported to be 20.3 million in 1990, and it significantly increased to 43.8 million in 2016, representing a remarkable rise of 116%. From 1990 to 2019, the incidence and prevalence of Alzheimer disease and other dementias rose by 147.95% and 160.84%, respectively. Projections indicate that the number of people affected by dementia is expected to reach 150 million by 2050, representing a 4-fold increase.[14]

The incidence of Alzheimer's disease doubles every 5 years after age 65. Age-specific incidence rates significantly increase from less than 1% yearly before 65 to 6% per year after 85. Prevalence rates increase from 10% after the age of 65 to 40% after 85. Incidence rates of Alzheimer's disease are slightly higher for women, especially after 85.[15]

Pathophysiology

Alzheimer disease is characterized pathologically by an accumulation of abnormal neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain. These pathological changes are accompanied by a loss of neurons, particularly cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain and the neocortex.

Two prominent pathophysiological hypotheses have been proposed based on these pathological findings:[16]

- The Cholinergic Hypothesis proposes that the reduced levels of acetylcholine (ACh) in the brain, resulting from neuronal loss in the Nucleus Basalis of Meynert, play a significant role in AD development. This hypothesis stems from the early loss of cholinergic neurons in AD, which highlights the importance of ACh in cognitive processes. Beta-amyloid is believed to negatively affect cholinergic function by causing cholinergic synaptic loss and impaired ACh release. Anticholinergics also adversely affect memory in elderly patients clinically.[17]

- The Amyloid Hypothesis is currently the most widely accepted pathophysiological mechanism for AD, especially in cases of inherited AD. The amyloid hypothesis suggests that amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide is derived from amyloid precursor protein (APP) through the actions of β- and γ-secretase enzymes. Usually, APP is cleaved by either alpha or beta-secretase, and the tiny fragments formed by them are not toxic to neurons—however, sequential cleavage by beta and then gamma-secretase results in 42 amino acid peptides (Aβ42). Elevation in levels of Aβ42 leads to aggregation of amyloid that causes neuronal toxicity. Aβ42 favors the formation of aggregated fibrillary amyloid protein over normal APP degradation.[18]

Genetic Basis of Alzheimer Disease

Down Syndrome, a genetic condition caused by trisomy 21, is strongly linked to the amyloid hypothesis in the context of AD research. In Down Syndrome, individuals have an extra copy of chromosome 21, leading to an additional copy of the APP gene.

Due to this genetic duplication, individuals with Down Syndrome have higher levels of APP, which increases the production of amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides. As a result, individuals with Down Syndrome are at a significantly increased risk of developing AD. It is estimated that approximately 40% to 80% of patients with Down Syndrome experience clinical AD by the fifth to sixth decade of life, and nearly 100% of them exhibit AD pathology, such as amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.[19]

AD can be inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder with nearly complete penetrance. This form of the disease is linked to mutations in 3 genes: the AAP gene on chromosome 21, Presenilin1 (PSEN1) on chromosome 14, and Presenilin 2 (PSEN2) on chromosome 1.

APP mutations may lead to increased production and accumulation of Aβ. On the other hand, PSEN1 and PSEN2 mutations interfere with the processing of gamma-secretase, leading to the aggregation of Aβ in the brain.

Although these mutations are relatively rare, accounting for approximately 5% to 10% of all AD cases, they are strongly associated with early-onset forms of the disease. The PSEN1 mutation is the most common, accounting for about 5% of all AD cases.[20]

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) is a lipid metabolism regulator with an affinity for beta-amyloid protein. There are 3 alleles for the Apolipoprotein E gene: ε2, ε3, and ε4. The ε4 allele of the APOE gene has been identified as a significant genetic risk factor for LOAD. Heterozygous carriers of the ε4 allele have a 3 times increased risk, while homozygous carriers face 15 times increased risk of developing AD. In patients with EOAD, the risk is even more pronounced in homozygous ε4 carriers and heterozygous ε4 carriers with a positive family history of AD.

The presence of the APOE e4 allele is considered one of the most crucial risk factors for sporadic Alzheimer disease.[20] While the ε4 allele increases the risk of developing the disease, it is essential to recognize that not everyone with the ε4 allele will develop AD, and many other factors play a role in the complex etiology of the disease.

Variants in the gene for the sortilin receptor, SORT1, which is essential for transporting APP from the cell surface to the Golgi-endoplasmic reticulum complex, have been found in familial and sporadic forms of AD.[11]

Histopathology

The typical histopathology of AD is characterized by the presence of 3 main elements:[21]

Neuritic Plaques: Neuritic plaques are spherical microscopic lesions featuring a core of extracellular amyloid beta-peptide (Aβ) surrounded by enlarged axonal endings. These Aβ depositions occur around meningeal and cerebral vessels and within the cortical gray matter in individuals with AD. Gray matter deposits are multifocal and coalesce, forming milliary structures called plaques. However, in some cases, brain scans have revealed the presence of amyloid plaques in some individuals without dementia. In contrast, other patients with diagnosed dementia who underwent multiple brain scans did not show evidence of plaques.

Neurofibrillary Tangles: Neurofibrillary tangles are fibrillary intracytoplasmic structures that form inside neurons and are composed of a protein called tau. The primary function of the tau protein is to stabilize axonal microtubules. Microtubules run along neuronal axons and are essential for intracellular transport. Tau helps maintain the integrity of microtubules and aids in their assembly along neuronal axons.

In AD, the aggregation of extracellular beta-amyloid leads to hyperphosphorylation of tau. This abnormal phosphorylation causes tau to become misfolded and form aggregates within the neurons. These tau aggregates take the shape of twisted paired helical filaments known as neurofibrillary tangles.

Neurofibrillary tangles first appear in the hippocampus and subsequently spread throughout the cerebral cortex. Tau-aggregates are deposited within the neurons.

Cortical Neuronal Degeneration: Among these degenerative changes, granulovacuolar degeneration of hippocampal pyramidal neurons is commonly observed. Cognitive decline in AD appears to be more closely related to a decrease in the density of presynaptic boutons from pyramidal neurons in specific layers of the cerebral cortex, particularly in laminae III and IV. The reduction in their density may have a more significant impact on cognitive function than the mere increase in the number of plaques characteristic of AD.

Braak and Braak Staging

A staging system known as the Braak and Braak staging has been developed to categorize the topographical progression of neurofibrillary tangles into 6 stages. This staging method is widely recognized and is integral to the diagnostic criteria for AD provided by the National Institute on Aging and Reagan Institute.

Neurofibrillary tangles have demonstrated a stronger correlation with AD severity than plaques.[22] This means that the amount of tau deposits in the brains of patients with AD correlates better with dementia severity than the amount of amyloid deposits. However, amyloid is a better-defining pathology for AD than other forms of dementia.

The relationship between amyloid and tau in the pathogenesis of AD is often likened to a "trigger and bullet" scenario.[23] Amyloid is considered the trigger that initiates the disease process. At the same time, tau, in the form of neurofibrillary tangles, acts as the bullet that leads to neurodegeneration and cognitive decline.

Accumulation of Aβ is a common feature in AD, with a higher prevalence of the more soluble Aβ40 than the Aβ42. In some AD patients, Aβ accumulates in the intracranial blood vessels, leading to the pathology known as cerebral amyloid angiopathy(CAA). The presence of CAA in AD has clinical implications, as it is associated with more significant cognitive impairment and possibly faster cognitive decline in affected individuals.[24]

On the other hand, vascular contribution to the neurodegenerative process of AD is not yet fully understood. However, research suggests that subcortical infarcts can increase the risk of dementia by 4-fold. Additionally, cerebrovascular disease can exaggerate the severity of dementia and accelerate its progression.[25][26][27]

History and Physical

Thorough history-taking and a comprehensive physical examination are crucial for diagnosing AD. Additionally, gathering information from family and caregivers is vital as some patients may lack insight into their disease. Assessing functional abilities, including basic activities of daily living(ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), provides valuable insights into the patient's cognitive and functional status. IADLs involve more complex planning and cognitive skills such as shopping, managing finances, tax filing, preparing meals, and housekeeping.

Obtaining information about the onset, pattern, and tempo of disease progression is essential for understanding the nature of the condition. This includes noting changes in memory, cognition, behavior, or functional abilities over time. The patient's medication history is also critical, as certain medications, especially those with anticholinergic effects, may impact cognitive function and should be considered in the evaluation.

In addition to medical history, it is essential to inquire about the patient's social history, including alcohol use and any history of street drug use. These factors can potentially influence cognitive function and should be considered during the diagnostic process.[28]

A comprehensive physical exam, including a detailed neurological exam and mental status assessment, is essential to evaluate the AD stage and rule out other potential conditions. A complete clinical assessment can provide a reasonable level of diagnostic accuracy for most patients.

A detailed neurological examination is essential to rule out other potential conditions. In AD, the neurological exam typically appears normal, except for anosmia. Anosmia is also found in patients with Parkinson disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and traumatic brain injury (TBI) with or without dementia, but not in individuals with vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) or depression.

A Mini-mental Status Exam (MMSE) or, preferably, a Montreal Cognitive Assessment Exam (MOCA) should be performed and documented as part of the cognitive neurological exam. The MOCA is more sensitive to evaluating patients with mild cognitive impairment than the MMSE.[29][30] Another effective cognitive screening test for primary care physicians is the Mini-Cog exam, which involves a clock drawing test and 3-item recall.[31] Notably, the results of the Mini-Cog are not significantly influenced by the individual's level of education.

In the advanced stages of AD, patients may exhibit more focal neurological signs, including apraxia and aphasia, frontal release signs, and primitive reflexes.

Patients may become mute and unresponsive to verbal requests as the disease progresses, leading to increased dependence on caregivers. They may eventually become confined to bed and eventually enter into a persistent vegetative state.

During a mental status examination, it is essential to assess various cognitive domains to evaluate the extent of cognitive decline in AD. These domains include concentration, attention, recent and remote memory, language skills, visuospatial functioning, praxis, and executive functioning. These assessments help to evaluate the extent of cognitive decline.

All follow-up visits for individuals with AD should include a thorough mental status examination to assess disease progression and the development of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Evaluation

From a primary care provider standpoint, when evaluating a patient suspected to be suffering from AD, the following tasks are essential:

- Review and confirm the medical and family history.

- Review the patient's medication list for medications that may potentially cause or worsen cognition.

- Perform a bedside cognitive assessment test, either an MMSE or MOCA, to evaluate the patient's cognitive function.

- Request blood tests to rule out any reversible causes of dementia

Routine laboratory tests do not reveal any specific abnormalities in AD. Complete blood count (CBC), complete metabolic panel (CMP), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and vitamin B12 levels are commonly conducted to exclude other potential causes of cognitive impairment.[32][33][34]

A brain computed tomography (CT) may reveal findings of cerebral atrophy and a widened third ventricle in individuals with AD. However, these findings are suggestive but not specific to AD, as they can also be present in other conditions and even in individuals experiencing normal age-related changes in the brain.

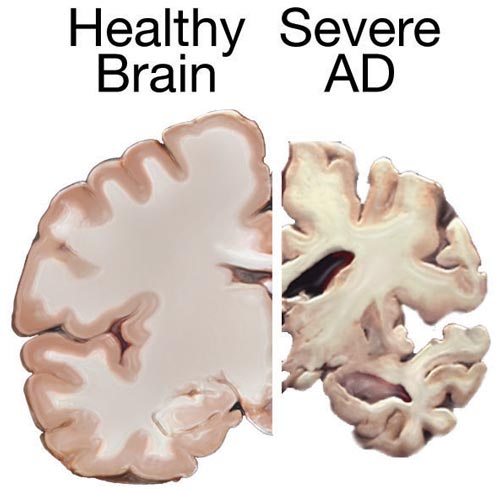

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is a superior structural neuroimaging modality compared to CT when evaluating individuals with dementia, including those suspected of having AD. In AD cases, MRI can reveal specific features compatible with the diagnosis. These include atrophy of the entorhinal cortex, followed by atrophy of the medial temporal cortex or hippocampi (see Image. Normal Versus AD Brain).

While MRI, like CT, may not make or confirm the diagnosis of AD, it can be beneficial in identifying specific patterns indicative of other neurodegenerative disorders with dementia, such as frontotemporal lobar degeneration, or specific radiological signs of multisystem atrophy, Creutzfeld-Jacob disease, or progressive supranuclear palsy.[35]

More recently, volumetric MRI has emerged as a valuable tool for precisely measuring changes in brain volume. In AD, volumetric MRI can reveal shrinkage in the medial temporal lobe, particularly the hippocampus. This hippocampal atrophy is considered a characteristic feature of AD and is associated with memory decline.

However, hippocampal atrophy is also linked to normal age-related memory decline, so the use of volumetric MRI for early detection of AD and distinguishing it from normal aging-related changes is still a subject of debate and research. A definite role for volumetric MRI to aid the diagnosis of AD is not yet fully established.[36]

Functional brain imaging techniques such as Positron Emission Tomography (PET), functional MRI (fMRI), and Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) are becoming increasingly valuable in mapping patterns of dysfunction in smaller brain areas of the medial temporal and parietal lobes. While these functional brain imaging techniques hold promise for early detection and monitoring of the clinical progression of AD, their role in the definitive diagnosis of AD is not fully established yet.

Electroencephalogram (EEG) is generally not a helpful diagnostic tool for AD and other neurodegenerative disorders. The EEG findings in AD are typically normal. Sometimes, it may reveal a generalized slowing of brainwave activity with no focal features.

Neuropsychological testing is the most reliable method for detecting mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in its early stages clinically.

Imaging and Biochemical Markers of AD

Over the past decade, significant progress has been made in developing neuroimaging and biochemical markers for diagnosing preclinical and early clinical stages of AD. However, these biomarkers are not widely available for routine clinical practice and are primarily utilized in AD research settings.

With the development of specific treatments for AD, especially monoclonal antibodies targeting Aβ, the importance of these disease markers becomes even more pronounced. Before initiating AD-specific therapies, it becomes crucial to accurately diagnose the presence and progression of AD pathology in patients.

Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET (FDG-PET) is a valuable functional imaging biomarker that can aid in the early and differential diagnosis of AD. FDG-PET may reveal specific metabolic impairments in certain brain regions, particularly the hippocampi, in individuals with early or preclinical AD.[37][38]

Amyloid PET is an important in vivo surrogate for Aβ pathology in the brain. It allows for the detection and visualization of amyloid deposition, a hallmark feature of AD. Amyloid PET is more specific for the pathological diagnosis of AD compared to other neurodegenerative disorders. However, its utilization is limited because amyloid deposition can be observed in normal elderly individuals. It best differentiates between neurodegenerative disorders caused by Aβ deposition and those related to other protein abnormalities, such as the deposition of α-synuclein or tau.[38]

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis is a helpful diagnostic tool in the preclinical stage of AD. It serves as a biomarker for AD pathology and can detect changes well before the onset of overt clinical symptoms. However, it does not help determine the severity of AD.

The main CSF biomarkers used in AD diagnosis are amyloid-beta 42 (Aβ42), phosphorylated tau (p-tau), and total tau (t-tau). In AD, there is decreased CSF Aβ42 and increased tau isoforms (both p-tau and t-tau).

The ratios of CSF biomarkers, such as Aβ42/40, have provided a more accurate and sensitive index of the underlying amyloid-related pathology in patients. The increase in CSF p-tau and t-tau levels directly reflects tau aggregation within the brain in AD.[39]

Genetic studies are not routinely recommended for the diagnosis of AD. However, they may be considered in specific cases for families with rare early-onset AD forms.

It is important to recognize that obtaining a definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer dementia, despite comprehensive clinical evaluation and testing, may not always be possible. Some patients may exhibit subjective cognitive complaints that can be objectively assessed but do not yet reach the level of impairment that interferes with their daily functioning. In such cases, the classification may be mild cognitive impairment (MCI) instead of dementia.

MCI represents an intermediate stage between normal age-related cognitive changes and the more severe cognitive impairment seen in dementia. Many people with MCI will develop some form of dementia within 5 to 7 years.[4]

Treatment / Management

Symptomatic Therapies of AD

Traditionally, there has been no cure for AD, and symptomatic treatment remains the primary approach in everyday clinical practice.[40][41][42]

Two categories of drugs are approved for treating AD: cholinesterase inhibitors and partial N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists.

Cholinesterase Inhibitors

Cholinesterase inhibitors function by increasing the levels of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that plays a role in nerve cell communication and is involved in learning, memory, and cognitive functions. Within this category, 3 drugs have received FDA approval for treating AD: donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine.[43][44][45]

- Donepezil:

- Medication of choice

- Used in AD with mild dementia

- Rapid and reversible inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase

- Once-daily dosing in the evening

- Rivastigmine:

- Used in MCI and mild dementia stages

- Slow, reversible inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase

- Available in an oral and transdermal formulation

- Galantamine:

- Approved in MCI and mild dementia stages

- Rapid, reversible inhibits of acetylcholinesterase

- Available as a twice-daily tablet or once-daily extended-release capsule

- Cannot be used in individuals with end-stage renal disease or severe liver dysfunction

The most common side effects of cholinesterase inhibitors include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Due to an increase in vagal tone, these medications can cause bradycardia, cardiac conduction defects, and syncope. They are contraindicated in patients with severe cardiac conduction abnormalities.

Partial N-Methyl D-Aspartate (NMDA) Memantine

Partial N-Methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist memantine blocks NMDA receptors, slowing down intracellular calcium accumulation. The FDA approves it for treating moderate to severe AD. Dizziness, body aches, headache, and constipation are common side effects.

Memantine can be combined with cholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, rivastigmine, or galantamine, especially in individuals with moderate to severe AD.[46]

Disease Modifying Therapies of AD

In the past, the treatment of AD has primarily focused on managing the symptoms. By the time a patient is diagnosed with AD, the pathological process in the brain has been present for over a decade. However, with advancements in our understanding of the pathophysiology of AD and improvements in diagnostic testing with imaging and biochemical markers, we can now detect preclinical and presymptomatic stages of the disease, even in individuals with MCI.

New and specific disease-modifying therapies are being developed, and the FDA has recently approved some. For example, Aducanemab was approved by the FDA in June 2020. The FDA recently approved Lecanemab. Donanemab is also expected to receive FDA approval soon. These monoclonal antibodies act by removing amyloid from the brain as immunotherapy. Remternetug is another one of these promising amyloid-targeting immunotherapy drugs in the pipeline.[47]

- Aducanemab received accelerated FDA approval in June 2020. It was shown to reduce amyloid-beta plaque in the brain. However, it missed the primary phase III trial endpoint of clinical improvement.[48]

- Lecanemab received accelerated FDA approval in January 2023. It reduced the amyloid-beta burden in the brain. The phase III trial showed a 27% slowing of disease progression.[49]

- Donanemab is expected to receive FDA approval in 2023. It reduced the amyloid-beta burden in the brain and slowed cognitive decline by 35%.[50]

Amyloid Related Imaging Abnormalities (ARIA)[51]

ARIA is an immune-mediated response to amyloid-targeting therapies in the cerebral vascular walls resulting in capillary leakage into perivascular spaces and hemorrhages of cortical and leptomeningeal arteries. There are 2 radiological types of ARIA: ARIA edema (ARIA-E) and ARIA hemorrhage (ARIA-H).

ARIA is a known side effect associated with amyloid immunotherapies. Apolipoprotein E4 allele and cerebral amyloid angiopathy findings in brain MRI are the most substantial risk factors for developing ARIA in patients treated with amyloid immunotherapies.

In the Aducanemab phase I/II trials, ARIA-E and ARIA-H were present in 26.1% to 26.7% and 26.1% to 30.5% of the patients, respectively. Notably, the majority of these patients were asymptomatic.[50]

Other Management Strategies in AD

In managing AD, addressing accompanying symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and psychosis is essential, especially in the mid to late stages of the disease.

It is advisable to avoid tricyclic antidepressants because of their anticholinergic activity, which can worsen cognitive impairment. Antipsychotic medications should be used cautiously for acute agitation when other interventions have been exhausted and the patient's or caregiver's safety is at risk. Other medications are generally tried before consideration of antipsychotics. These generally include SSRI antidepressants such as citalopram and anticholinesterase such as donepezil.

Second-generation antipsychotics are generally favored over first-generation antipsychotics because of their safety and less extrapyramidal side effects. FDA just approved Brexpiprazole in May 2023 for treating agitation associated with dementia due to AD.[52] However, their limited benefits should be weighed against the small risks of stroke and increased mortality.

The general principle in using antipsychotics is to use the lowest dose that may help the patient's agitation. Benzodiazepines should not be used because they may worsen delirium and agitation in these patients.

Simple strategies such as creating a familiar and safe environment, monitoring and addressing personal comfort needs, providing security objects, redirecting attention, removing potentially hazardous items like doorknobs, and avoiding confrontational situations can be highly beneficial in managing behavioral issues.

Addressing mild sleep disturbances is essential to minimize caregiver burden and improve the quality of life for individuals with AD. Several non-pharmacological strategies can be incorporated, such as exposure to sunlight, providing daytime exercise, and establishing a bedtime routine. These interventions can help regulate the sleep-wake cycle and promote better sleep patterns.

The expected benefits of these treatments are modest. Treatment should be stopped or modified if no significant benefits are seen or the patient experiences intolerable side effects.

Regular aerobic exercise has been shown to slow the progression of AD.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of Alzheimer dementia includes considering conditions such as pseudodementia or depression, Lewy body dementia, vascular dementia, and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Other disorders to be considered and excluded have age-associated memory impairment, alcohol or drug abuse, vitamin-B12 deficiency, individuals undergoing dialysis, thyroid problems, and the potential impact of polypharmacy.[53]

Lewy Body Dementia (DLB): Approximately 15% of cases of dementia can be attributed to DLB. The DSM-5 includes it within Neurocognitive Disorders with Lewy Bodies. Histologically, patients with DLB have cortical Lewy bodies, and their concentration correlates with the severity of dementia.

These bodies are spherical intracytoplasmic inclusions with a dense circular eosinophilic core surrounded by loose fibrils. The core contains aggregates of proteins α-synuclein and ubiquitin.

Patients with Lewy Body dementia have core clinical features (fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, ≥1 symptom of Parkinson disease with onset the development of cognitive decline), suggestive clinical features (REM sleep behavior disorder and severe antipsychotic sensitivity), and indicative biomarkers (123-MIBG demonstrates low uptake, SPECT or PET shows reduced dopamine transporter uptake in basal ganglia, and PSG shows REM sleep without atonia).

A probable diagnosis is made if a patient has 2 core features or 1 suggestive feature with 1 or more core features. A possible diagnosis is given if the patient has only 1 core feature or 1 or more suggestive features.[54]

Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD): It accounts for 5% to 10% of all dementia cases and typically presents at a mean age of 53, more commonly affecting men than women. Patients with FTD experience personality and behavioral disturbances with or without language impairment, which precede dementia with an insidious onset. The term "Pick disease" was historically used for FTD due to intraneuronal inclusions known as "Pick bodies" in histological findings.

FTD is categorized into 2 subtypes: behavioral variant and language variant.

For the behavioral variant, a possible diagnosis requires the presence of 3 of the following symptoms: disinhibition, apathy, loss of sympathy, stereotyped or compulsive behaviors, hyperorality, and decline in social cognition and executive abilities. The language variant has a decline in language ability. In addition to these symptoms, evidence of genetic mutation or frontal and temporal lobe involvement on CT or MRI is required for probable diagnosis. Importantly, patients with FTD typically retain their visuospatial abilities despite the cognitive decline.[55]

Dialysis Dementia: Dialysis dementia is a neurologic complication that can arise from chronic dialysis treatment. It can be due to various factors, such as vascular causes (as dialysis patients are at a higher risk of stroke), metabolic abnormalities, or the dialysis process. In the past, it was associated with aluminum toxicity, but now, its occurrence has decreased with the use of aluminum-free substances. The precise mechanism behind dialysis dementia remains unclear.[56]

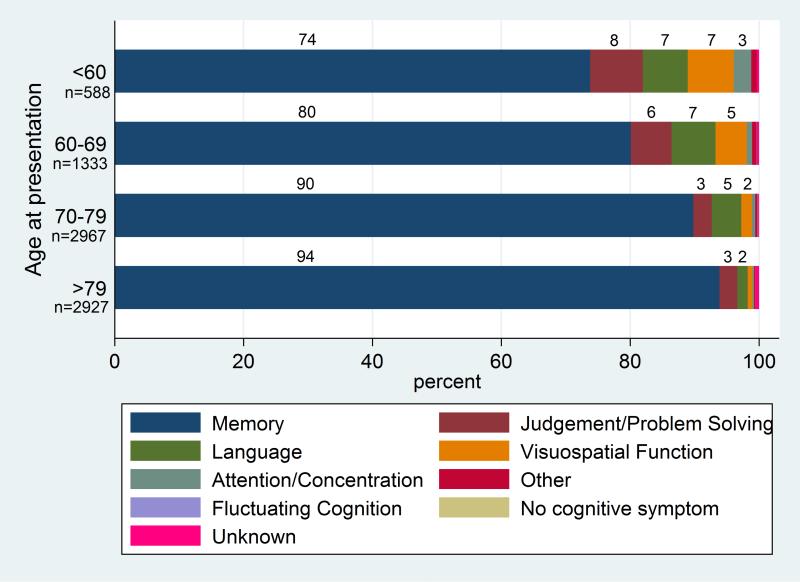

It is important to note that the initial symptoms of AD can vary depending on the age of diagnosis.[57] Memory impairment remains the most common initial symptom of AD. Among patients aged 70 to 79, approximately 90% present with memory impairment as the first symptom. This percentage increases to 94% for patients older than 79. However, in patients diagnosed with AD younger than 60, around 74% initially exhibit memory impairment, with about a quarter presenting with impaired judgment and visuospatial functions. Overall, EOAD patients are more likely to have atypical AD presentations than those with LOAD (see Chart. Cognitive Symptom Presentation).[58]

Some atypical presentations of AD include:

- The multidomain amnestic syndrome affects multiple areas of cognition, especially language and spatial orientation, with relative memory sparing in the early stages.

- Posterior cortical atrophy, characterized by progressive cortical visual impairment with features such as simultagnosia, object and space perception deficits, acalculia, alexia, and oculomotor apraxia, with relative sparing of anterograde memory, non-visual language function, behavior, and personality. Neuroimaging shows occipitoparietal or occipitotemporal atrophy.[59]

- Primary progressive aphasia(PPA) is characterized by progressive language difficulty with relative sparing of memory and other cognitive functions in early disease. While most patients with PPA have a pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia, the logopenic form of PPA has typical AD pathology.[60]

- Dysexecutive or frontal variant patients have impairment in executive functions relative to memory loss.

Staging

Preclinical or Presymptomatic

In this preclinical stage, individuals are asymptomatic, but there is definite laboratory evidence of AD pathology. Identifying the biomarkers can aid in diagnosing Alzheimer disease at this stage. Low levels of amyloid and increased tau proteins in CSF are potential biomarkers, although they are not specific to AD. Combining various variables, such as ApoE4 positivity, scores on cognitive tests like the paired associates immediate recall test and digits symbol substitution test, increased tau protein in CSF, and measurements of right entorhinal cortex thickness and right hippocampal volume on MRI, can help predict the progression to MCI from this preclinical stage.

Mild Cognitive Impairment

In this stage, patients experience MCI with either memory or non-memory domain impairment, such as executive ability or language function. Despite these cognitive changes, these individuals continue to work, socialize, and function independently. The progression rate from MCI to dementia is approximately 10% per year. Risk factors for this progression include the severity of impairment at the time of diagnosis and other established risk factors for AD.

Dementia

In this stage, patients experience incapacitating memory impairment with notable language changes, including anomia, paraphasic errors, reduced spontaneous verbal output, and a tendency to use circumlocution to compensate for forgotten words. Additionally, a decline in visuospatial abilities leads to difficulties in navigation within familiar surroundings and constructional apraxia.

Around 20% to 40% of patients with AD may experience delusions. Visual hallucinations are more common, although auditory and olfactory hallucinations can also occur. Disruptive behaviors are prevalent in almost 50% of the patients. Patients often lose their typical circadian sleep-wake pattern in this stage, leading to fragmented sleep. Additionally, motor vehicle crashes are more frequent in patients with AD.

Prognosis

Alzheimer disease is a relentlessly progressive condition. On average, individuals aged 65 or older diagnosed with AD may have a life expectancy of about 4 to 8 years. However, some individuals with AD may live up to 20 years after the initial signs of the disease.

The overall decline in physical and immune function, coupled with impaired mobility and difficulty swallowing, makes Alzheimer's patients vulnerable to infections, particularly pneumonia, which is the most common cause of death.[61]

Complications

According to CDC's National Center for Health Statistics 2023, AD is the 6th leading cause of death, with nearly 120,000 deaths annually. AD predominantly affects individuals over 65, putting them at higher risk of experiencing complications that can significantly impact their health and well-being. Complications associated with AD can be broadly categorized into mental/behavioral and physical challenges. They are listed as follows:[62][63]

Mental/Behavioral

- Depression is a prevalent comorbidity among patients with AD, adding to the complexity of managing their condition. Common symptoms of depression in patients with AD include mood changes, sleep disturbances, social withdrawal, and difficulty concentrating.

- Agitation and delirium, including sundowning, are common occurrences in the more advanced stages of AD, posing challenges for patients and caregivers. Managing these symptoms is essential for ensuring the safety and comfort of individuals with AD. However, the use of antipsychotic medications to treat these issues has been associated with increased mortality and other adverse effects.

- Wandering

Physical

- Fever and infections, particularly respiratory and urinary infections, are prevalent among elderly individuals with AD. Swallowing difficulties can lead to aspiration pneumonia, further complicating their health condition.

- Dehydration and malnutrition

- Falls

- Bladder and bowel problems

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation and physical activity play crucial roles in treating and preventing dementia. Regular physical activity has been shown to benefit individuals with dementia significantly. It can improve cognitive function, especially executive functioning, which helps reduce the fall risk and enhances the ability to perform activities of daily living. Furthermore, physical activity has reduced the incidence of neuropsychiatric symptoms like depression.[64]

Although specific clinical practice guidelines for exercise in dementia patients are not yet established, ongoing research continuously strives to determine the most effective type, intensity, and duration of exercise. Studies suggest moderate to high-intensity exercise may offer greater benefits than lower-intensity activities.[65][66]

Caregivers and the care team play a critical role in ensuring continuity of care and providing the necessary support for dementia patients. Due to limitations in education retention, regular reinforcement of information and guidance is essential to help individuals with dementia maintain their functional abilities and quality of life.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Given its high prevalence, the care of patients with AD is of global concern. However, there are no specific requirements for professional development education or accreditation for healthcare providers in AD care.

It is crucial to prioritize patient and care provider education to enhance the quality of care for AD patients. An interprofessional team-based approach involving medical doctors, social workers, therapists, and family members is essential for comprehensive care. Additionally, bridging the gap between theoretical education and its practical application in real-life settings is vital to ensure adequate care delivery for AD patients.[67]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive and behavioral impairments that eventually disrupt daily activities. Unfortunately, AD has no cure, and its progression varies from person to person. Early diagnosis of Alzheimer disease remains challenging, as no definitive laboratory or imaging tests are available for confirmation.

The drugs used to treat AD provide only modest benefits in mild disease but often come with numerous side effects that patients may not tolerate. The impact of AD is not limited to the individual affected; it also significantly affects the family, as patients may exhibit wandering behavior, falls, behavioral issues, and memory loss. These challenges often lead to patients requiring institutional care due to the increasing difficulty of managing their condition at home.

Given the complex nature of Alzheimer's disease, an interprofessional team approach is highly recommended. Various guidelines and recommendations have been developed to address the approach, monitoring, and treatment of patients with Alzheimer dementia. While no single measure can prevent or halt the disease's progression, a collaborative effort among healthcare professionals is crucial in ensuring the safety and quality of life for individuals with AD.

Several healthcare workers play critical roles in caring for patients with AD to ensure their well-being and dignity. A few key healthcare workers are as follows:

- Physical therapists and occupational therapists for therapy and exercise. There is now ample evidence that exercise can help reduce the progression of the disease.[65]

- Nurses play a crucial role in educating patients and their families about medications, lifestyle changes, and performing daily living activities. They also support self-reporting any worsening symptoms, helping monitor the patient's condition, and managing their care.

- Pharmacists ensure the safe and appropriate use of medications, avoiding polypharmacy and minimizing the risk of adverse effects.

- Clinicians, including physicians and neurologists, monitor the patient's progress, conduct regular evaluations, and adjust treatment plans as needed. They work to enhance the patient's overall quality of life and manage any medical complications that may arise.

- Caregivers are essential team members, providing direct support to the patient in daily living activities, managing behavioral challenges, and offering emotional and physical assistance.

- Social workers help ensure the patient has a robust support system addressing social and emotional needs. They may assist in accessing community resources, support groups, and respite care for caregivers.

- Dietitians ensure the patient maintains a healthy diet tailored to their needs.

- Mental health nurses specialize in addressing the psychological and emotional aspects of AD, providing support to both the patient and their caregivers as they cope with the challenges of the disorder.

Outcomes

Alzheimer disease initially manifests with impaired memory, but as it progresses, individuals may develop a range of severe cognitive and behavioral symptoms like depression, anxiety, anger, irritability, insomnia, and paranoia. As the disease progresses, most will require assistance with daily living activities. The disease's relentless course often necessitates increasing aid with daily living activities as cognitive and functional abilities decline. In the advanced stages, even basic tasks like walking can become challenging, and many individuals may face difficulties with eating or develop swallowing problems, putting them at risk of aspiration pneumonia.

The time from diagnosis to death in AD is variable, with some individuals passing away within 5 years, while others may survive for up to 10 years or more. However, throughout the course of the disease, the quality of life is significantly impaired. While an interprofessional approach to managing patients with AD is recommended, an analysis of several studies indicates that this approach has not considerably impacted patient care. Nevertheless, because of the heterogeneity of previous studies, more robust and well-designed research will be required to determine the most effective approach for managing these patients.[68]