Continuing Education Activity

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic, inflammatory disease of the axial spine. Chronic back pain and progressive spinal stiffness are the most common features of this disease. Involvement of the spine, sacroiliac joints, peripheral joints, digits, and entheses are characteristic. Impaired spinal mobility, postural abnormalities, buttock pain, hip pain, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, and dactylitis are all commonly associated with ankylosing spondylitis. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of ankylosing spondylitis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Differentiate AS from other conditions with similar presentations.

- Select appropriate diagnostic imaging modalities for evaluating AS-related changes.

- Apply knowledge of available pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for AS.

- Coordinate care and referrals for patients with AS, ensuring a multidisciplinary approach to address all aspects of the disease.

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic, inflammatory disease primarily affecting the axial spine that can manifest with a range of clinical signs and symptoms. The hallmark features of the condition include chronic back pain and progressive spinal stiffness. AS is characterized by the involvement of the spine and sacroiliac (SI) joints and peripheral joints, digits, and entheses.

AS often leads to impaired spinal mobility and can result in postural abnormalities. Patients can also experience buttock pain and hip pain. Peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, and dactylitis ("sausage digits") are all associated with AS.

In addition to skeletal involvement, AS can affect various organs outside the joints. These extraarticular manifestations of AS include inflammatory bowel disease (affecting up to 50% of individuals), acute anterior uveitis (seen in 25%-35% of cases), and psoriasis (approximately 10% occurrence).

AS is additionally linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease which is believed to stem from the systemic inflammation present in individuals with AS. Pulmonary complications are also associated with AS, as diminished chest wall expansion and limited spinal mobility can predispose individuals to a restrictive pulmonary pattern.

Finally, individuals with AS are at least twice as likely to experience vertebral fragility fractures. Additionally, they face an increased risk of atlantoaxial subluxation, spinal cord injury, and, rarely, cauda equina syndrome.[1][2][3]

Etiology

The cause of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) remains largely unknown. However, there appears to be a correlation between the prevalence of AS and the presence of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 in a given population. Among individuals who are HLA-B27 positive, the prevalence of AS is approximately 5% to 6%. In the United States, the prevalence of HLA-B27 varies among ethnic groups. A 2009 survey reported rates of HLA-B27 prevalence as 7.5% among non-Hispanic Whites, 4.6% among Mexican-Americans, and 1.1% among non-Hispanic Blacks.[4][5]

Epidemiology

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) commonly presents in individuals younger than 40, with approximately 80% of patients experiencing their first symptoms before age 30. Less than 5% are diagnosed after the age of 45. AS is more prevalent in men than women. Moreover, there is an increased risk of developing AS in relatives of affected patients.[6]

Pathophysiology

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory disease that typically presents gradually and without obvious early symptoms. The disease is characterized by progressive musculoskeletal, and often extraskeletal, signs and symptoms. The rate of disease progression can vary among individuals.

The primary pathology of spondyloarthropathies, including AS, involves enthesitis. This chronic inflammation involves infiltrating immune cells such as CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes and macrophages. Cytokines, particularly tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), are also important in the inflammatory process. They contribute to inflammation, fibrosis, and ossification at sites affected by enthesitis.

History and Physical

In suspected cases of AS, a comprehensive evaluation of the entire body is recommended due to the systemic nature of the disease and its potential involvement in multiple organ systems. Back pain is a common complaint among patients. The characteristic type of back pain in AS is "inflammatory" in nature.

The presence of inflammatory back pain is characterized by at least 4 of the following 5 features: onset of symptoms before the age of 40, gradual and insidious onset, relief with exercise, lack of improvement with rest, and nocturnal pain with improvement upon arising. Additionally, spinal stiffness, limited mobility, and postural changes, particularly hyperkyphosis, are frequently observed.

During the evaluation, the patient's history and physical examination should address all body systems, as AS can manifest with axial and peripheral musculoskeletal symptoms and extraarticular features. A detailed medical history should be obtained to identify or rule out associated conditions such as psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, and uveitis, among others, that may be correlated with AS.

Evaluation

Laboratory findings in ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are typically nonspecific but may provide supportive evidence for diagnosis. Approximately 50% to 70% of patients with active AS show elevated levels of acute phase reactants, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP). However, a normal ESR and CRP should not be used to exclude the possibility of AS.[7][8][9]

Several imaging abnormalities, especially those affecting the spine and sacroiliac joints, are associated with AS. Evidence of sacroiliitis on imaging, whether radiographic or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is considered a major inclusion criterion for AS according to the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) 2009 axial spondyloarthritis criteria.

A standardized plain radiographic grading scale exists for sacroiliitis. This scale ranges from normal (0) to most severe (IV), as detailed below.

- 0: Normal SI joint width, sharp joint margins

- I: Suspicious

- II: Sclerosis, some erosions

- III: Severe erosions, pseudo dilation of the joint space, partial ankylosis

- IV: Complete ankylosis

During the initial years of AS, plain radiographic changes in the SI joints can be subtle; however, these changes will usually become more evident over the first decade of the disease. The most noticeable abnormalities on radiographs are subchondral erosions, sclerosis, and joint fusion. These changes are typically symmetrical, affecting both sides of the SI joints similarly.

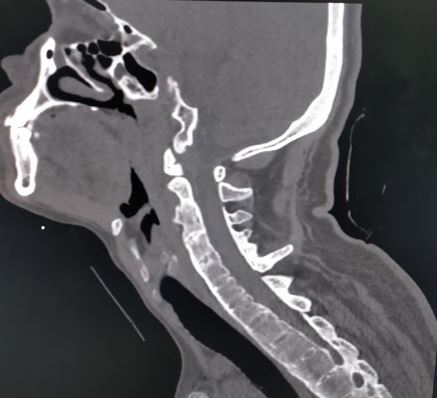

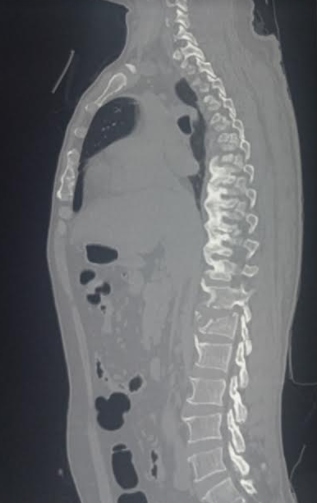

Throughout AS, a series of distinct radiographic changes characteristics can progressively develop. In the early stages, a notable sign is the "squaring" of vertebral bodies, which is best visualized on lateral X-rays. This squaring occurs due to inflammation and bone deposition, resulting in the loss of normal concavity of the anterior and posterior borders of the vertebral body. Additionally, early-stage radiographs may reveal Romanus lesions, also known as "shiny corner signs," characterized by small erosions and reactive sclerosis at the corners of the vertebral bodies.

Late-stage findings on radiographs include ankylosis (fusion) of the facet joints of the spine, the presence of syndesmophytes, and calcification of the anterior longitudinal ligament, supraspinous ligaments, and interspinous ligaments. This calcification may be seen on imaging as the "dagger sign," appearing as a single radiodense line vertically running down the spine on frontal radiographs.

The classic radiographic finding in late-stage AS is the "bamboo spine sign," which refers to vertebral body fusion by syndesmophytes. The bamboo spine typically involves the thoracolumbar or lumbosacral junctions. This spinal fusion predisposes the patient to progressive back stiffness.

While plain radiography is the first-line imaging modality in AS, additional imaging with MRI may be necessary to detect more subtle abnormalities, such as fatty or inflammatory changes. MRI can reveal active inflammatory lesions in the SI joints. These appear as bone marrow edema (BME) on short tau inversion recovery (STIR) and T2-weighted images with fat suppression. It should be noted that the presence of BME on MRI can also be seen in up to 23% of patients with mechanical back pain and 7% of healthy individuals.[10]

Treatment / Management

The treatment goals for AS aim to alleviate pain and stiffness, preserve axial spine mobility and functional ability, and prevent spinal complications. Non-pharmacological interventions should include regular exercise, postural training, and physical therapy.

First-line medication therapy involves using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on a daily, long-term basis. If NSAIDs do not provide adequate relief, they can be combined with or substituted for tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNF-Is) such as adalimumab, infliximab, or etanercept. The response to NSAIDs should be assessed 4 to 6 weeks after initiation, while the response to TNF-Is should be evaluated after 12 weeks.

Systemic glucocorticoids are not recommended for treating AS, but local steroid injections may be considered for specific cases. Specialist referrals may be warranted based on the patient's clinical presentation, potential complications, and extra-articular manifestations of the disease. Rheumatologists may assist in the formal diagnosis, management, and monitoring of AS, while dermatologists, ophthalmologists, and gastroenterologists may assist with associated non-musculoskeletal features of the disease.[1]][11]][12]

Differential Diagnosis

Certain diseases and conditions can mimic ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and must be ruled out. These include, but are not limited to:

- Mechanical low back pain

- Lumbar spinal stenosis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH)

Each of these diagnoses has similarities with AS, but their differences should be ruled in or out for accurate diagnosis.

Mechanical back pain and AS can be distinguished based on several factors. The onset of symptoms is a key differentiating factor, as mechanical back pain can occur at any age, while AS typically presents before age 40. Unlike AS, mechanical back pain improves with rest, and morning stiffness is mild and short-lived. Mechanical back pain is not associated with peripheral arthritis or the extraskeletal manifestations commonly seen in AS.

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is a condition characterized by the narrowing of the spinal canal, which leads to spinal cord compression. Like AS, it may present with chronic back pain and morning stiffness. However, unlike AS, LSS usually presents in individuals older than 60 and is not associated with peripheral arthritis or extraskeletal features. The response to NSAIDs in LSS can vary among patients.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is another chronic inflammatory disorder of the joints that often presents with progressive back pain and morning stiffness in patients 40 or younger, similar to AS. However, peripheral arthritis is highly prevalent in RA, but not in AS. Another distinguishing feature of RA is the presence of rheumatoid nodules, which are pathognomonic for RA and are not usually observed with AS.

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is a degenerative disorder characterized by ossification in the spine occurring primarily in the anterior longitudinal ligament, paravertebral tissues, and peripheral aspect of the annulus fibrosus. Like AS, DISH may present a history of postural changes and back pain. Unlike AS, DISH is not an inflammatory disorder and lacks inflammatory characteristics such as morning stiffness or improvement with exercise but not with rest. Also, DISH does not exhibit any evidence of sacroiliitis on radiographic imaging.

Prognosis

Individuals who experience an earlier onset of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are associated with poorer functional outcomes. However, it is important to note that severe physical disability is relatively uncommon in AS. Most patients can maintain a reasonable level of physical function and lead active and fulfilling lives.

Patients with severe and long-standing disease have an increased risk of mortality compared to the general population. The increased mortality is primarily attributed to cardiovascular complications.

Complications

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) has articular and extra-articular complications. These include:

- Chronic pain and disability

- Aortic regurgitation

- Pulmonary fibrosis

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Mood disorders

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Rehabilitation

Exercise programs have demonstrated significant benefits in managing ankylosing spondylitis, addressing pain management, flexibility, mobility, and overall function. While there is no specific protocol universally recommended for AS management, multiple studies have shown improvements across various exercise programs, including home exercise programs and group therapies.

Hydrotherapy is one area widely cited for its cardiovascular benefits and pain management effects in individuals with AS. Respiratory and postural exercises are important in AS, as the disease process can impact proper breathing mechanics and posture.[13][14][15][16]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is vital in the management of ankylosing spondylitis (AS). Patients should be educated about the chronic nature of the disease, the medications used for treatment, and their potential side effects.

There should be an emphasis on regular exercise programs that reduce symptoms. Physical therapy, including water therapy and swimming, can be highly beneficial in reducing symptoms, improving functionality, and maintaining overall fitness.

Given the potential of pulmonary involvement in AS, it is essential to emphasize the importance of smoking cessation.

Pearls and Other Issues

There should be a high index of suspicion for vertebral fractures in patients with AS, even following minor trauma. Individuals with AS are at increased risk of vertebral fracture and subluxation, especially of the cervical spine. Therefore, these patients are more susceptible to neurologic compromise.

Prevention of disease morbidity can be achieved with exercise, physical therapy, tailored pharmacologic intervention, and regimented follow-up appointments with providers.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a systemic disorder that can affect multiple organ systems. Therefore, an interprofessional team approach is recommended to prevent morbidity and provide comprehensive care to individuals with AS. An effective interprofessional team may consist of healthcare professionals such as the following:

- Rheumatologists are typically at the forefront of AS care, providing diagnosis, disease monitoring, and guidance on medication management.

- Primary care physicians are vital in monitoring overall health, coordinating care, and addressing comorbidities.

- Gastroenterologists assess for inflammatory bowel disease.

- Ophthalmologists assess for anterior uveitis.

- Cardiologists assess for heart block or valvular involvement

- Physical therapists and occupational therapists help design exercise programs, provide pain management strategies, and improve mobility and functionality.

- Neurologists assess for nerve compression syndromes.

- Pharmacists monitor for drug interactions and dependence on analgesics.

- Nurses provide ongoing support, patient education, and coordination of care.

Numerous reports have provided evidence supporting the effectiveness of an interprofessional approach in managing ankylosing spondylitis leading to functional improvement, pain reduction, and increased quality of life.[17][18] (Level II)

Evidence-based Medicine

A meta-analysis of multiple studies has demonstrated that individuals who participate in an exercise program experience much better outcomes than those who lead sedentary lifestyles. (Level II) However, it is important to note that patients with high symptom burden during AS diagnosis usually exhibit poor response rates and are often lost to follow-up. To address this issue, implementing an early education program can improve patient engagement and retention.[19][20][21] (Level V)