Introduction

The anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) is one of the lateral branches of the basilar artery which supplies various structures of the posterior cranial fossa, most importantly the cerebellum and pons.

The anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) is one of the lateral branches of the basilar artery which supplies various structures of the posterior cranial fossa, most importantly the cerebellum and pons.

The anterior inferior cerebellar artery is commonly the most caudal branch of and arises from the lateral wall of the lower or middle third of the basilar artery. Infrequently, however, the AICA originates from the distal vertebral artery. Anterior inferior cerebellar artery usually originates as a single trunk but duplication of the main trunk is a well-known variation. The AICA exists in hemodynamic balance with the other cerebellar arteries, namely, the superior cerebellar (SCA) and posterior inferior cerebellar (PICA), the sizes of these vessels being highly variable depending on which is the dominant arterial supply to the cerebellar cortex.

After originating from the lateral wall of basilar artery it courses posterolaterally, ventral to the pons in the prepontine cistern, then enters the cerebellopontine angle and continues along the anterior cerebellar surface. The main trunk bifurcates into the superior and inferior trunks at the pontomedullary junction adjacent to the exit of facial and vestibulocochlear nerves from the brain stem.

The anterior inferior cerebellar artery can be divided into four segments including the anterior pontine (close to the abducent nerve), lateral pontine (close to the facial and vestibulocochlear nerves), flocculopeduncular, and cortical segments. The lateral pontine segment can be further divided into pre-meatal, meatal, and postmeatal segments based on their relationship with the internal auditory meatus.

The labyrinthine artery, also called the internal auditory artery is in most cases a branch of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, less commonly it arises directly from the basilar artery.

The anterior inferior cerebellar artery supplies the middle cerebellar peduncle, lower lateral pons, anteroinferior surface of the cerebellum, flocculus and the choroid plexus of the lateral ventricle.

The labyrinthine artery supplies labyrinth and cochlea of the inner ear along with facial (CN VII) and vestibulocochlear (CN VIII) nerves.[1][2][3]

The process of angiogenesis for all blood vessels begins with the angioblast, which arises from the mesoderm.[4] Large blood vessels, such as the dorsal aorta, are formed from the coalescence of angioblast in situ. Other large blood vessels, such as the endocardium, are formed by the migration of angioblasts from other sites. Vessels of the central nervous system, like the AICA, arise from the sprouts of existing larger blood vessels.

The vertebral arteries, which give rise to the basilar artery, are a derivative from connections of the lateral branches of the dorsal intersegmental arteries. These are paired embryonic branches of the aorta part of which later become cervical intersegmental. The lateral branches of the cervical intersegmental join to become vertebral arteries.[5]

The AICA develops as a branch of the longitudinal neural system.

With advancements in Computed Tomography (CT) technology, it has become easier to more accurately visualize the vascularization of small vessels, making it simpler to note variations that were typically seen only during an autopsy.[6] Some of these advances have been useful in studying the variations of the arteries of the posterior fossa including the anterior inferior cerebellar artery. In about 99% of patients, the anterior inferior cerebellar artery arises from the basilar artery with about 75% of cases originating from the lower third.[2] It may also stem from the vertebrobasilar junction as seen in about 9% of cases.[2] The AICA has also been cited to give rise to the labyrinthine artery in about 90% of individuals.[2] The most common variation noted is the absence of a visible anterior inferior cerebellar artery, with its absence more common on the left side. In this variation, the anterior inferior cerebellar artery will either originate from the vertebral artery or the posterior inferior cerebellar arteries directly. Duplication of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery has also been noted but is rare. The double origin anterior inferior cerebellar artery has also been pointed out in the right anterior inferior cerebellar artery in which one branch originates from the basilar artery and the other from the vertebral artery.[6] Some anastomoses have also been noted between the rostral part of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery and the superior cerebellar artery (SCA) and between the caudal part of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery and the posterior inferior cerebellar arteries. Other common variations that occur in the branches of the basilar artery that may affect the AICA are the agenesis of the right posterior inferior cerebellar arteries or the left posterior inferior cerebellar arteries. The agenesis of the posterior inferior cerebellar arteries may create an inverse relationship between the anterior inferior cerebellar artery and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries. In this case of agenesis of the posterior inferior cerebellar arteries, there will be a well-developed anterior inferior cerebellar artery with the posterior inferior cerebellar arteries arising from an anterior inferior cerebellar artery/posterior inferior cerebellar arteries common trunk.[7] The prevalence of this variation as reported in the literature is about 20% to 24%.[7]

Surgical procedures in the arteries of the posterior fossa require a great fund of anatomical knowledge. Understanding anatomical variations are the first step in carrying out successful procedures. For example, the position (proximal or distal anterior inferior cerebellar artery) and nature of an aneurysm (ability to maneuver micro-catheter into an aneurysm) are important factors that determine if surgery or endovascular treatment will be used. With a proximal anterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysms, a skull base surgery is mostly used with an aneurysm being clipped or trapped and resected.[8] A skull base approach can be very challenging because large exposures are needed and due to the critical relationship between AICA and other neurovascular structures like abducens, facial, vestibulocochlear nerves, perforating pontine arteries and the trigeminal, glossopharyngeal and vagus nerve.[8]

Endovascular treatment is mostly used in distal anterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysms and has been discouraged in proximal anterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysms.[9] Endovascular treatment has become useful in treating aneurysms, for example, using coiling embolization to treat aneurysms of the AICA which originate past the origin of pontine branches, in the distal segments of the artery, in patients with good collateral circulation via the PICA or SCA branches.[9]

Clinical syndromes associated with the anterior inferior cerebellar artery may be secondary to an infarction in its vascular territory, aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, or, infrequently, mass effect on adjacent structures from an aneurysm.

AICA infarction may be of cardio-embolic or athero-embolic origin (rupture of atherosclerotic/arteriosclerotic plaque). Patients present with a lateral pontine syndrome, also known as the AICA syndrome and have a sudden onset of severe vertigo, nausea, vomiting, nystagmus (vestibular nuclei), ipsilateral hemiataxia (middle cerebellar peduncle), ipsilateral, lower motor neuron facial weakness, ipsilateral loss of lacrimation and salivation, ipsilateral loss of taste from anterior 2/3rd of tongue and loss of corneal reflex (CN VII nucleus and nerve), ipsilateral loss of pain and temperature from the face (spinal trigeminal nucleus), ipsilateral hearing loss and tinnitus (cochlear nuclei) and ipsilateral Horner's syndrome (descending sympathetic tracts). There is a contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation from the body (lateral spinothalamic tract). It is important to distinguish the AICA syndrome from lateral medullary syndrome caused by infarction in the distribution of the PICA which presents with severe dysphagia, dysarthria, and dysphonia and also does not have lower motor facial paralysis, loss of lacrimation and taste which are prominent features of the AICA syndrome.[3]

As reported in the literature, aneurysms of the posterior fossa account for 8% to 12% of all cerebral aneurysms, with aneurysms of anterior inferior cerebellar artery accounting for about 1% to 2% of all aneurysms.[7][10] The most common site of an aneurysm formation is the basilar-anterior inferior cerebellar artery junction.[1][7] The cause of an aneurysm in the anterior inferior cerebellar artery can be due to hemodynamic stress on the weak arterial wall at a branch point, due to a high flow arteriovenous malformations (AVM) or due hemangioblastoma or a location that was exposed to radiation treatment.[11] As stated above, the anterior inferior cerebellar artery can be divided into four segments. The anterior pontine (close to the abducent nerve), lateral pontine (close to the facial and vestibulocochlear nerves), flocculopeduncular segment, and cortical segment. Anterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysms, are usually saccular and located in the anterior pontine segments.[1]

In very rare case reports, aneurysms have been noted in the distal anterior inferior cerebellar artery with the aneurysms mainly being dissecting or fusiform and rarely associated with bifurcation with about 55.5% located near the meatal loop.[9][12][9] Patients with an anterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysm that is more peripherally located may have a cerebellopontine angle mass effect (sudden hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo due to the involvement of the labyrinthine artery, facial paresis due to involvement of the facial nerve, gait ataxia, dysmetria due to the involvement of the middle cerebellar peduncle with subarachnoid hemorrhage, acute severe headache, nausea, vomiting, or sudden coma.[9][3]

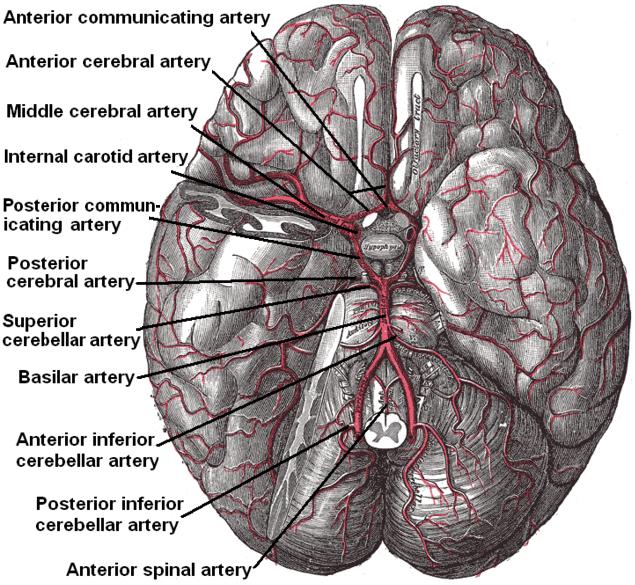

Arterial Circulation of the Brain. This inferior view shows the circle of Willis at the base of the brain formed by the anterior communicating, anterior cerebral, middle cerebral, internal carotid, posterior communicating, posterior cerebral, and basilar arteries. The temporal pole of the cerebrum and a portion of the cerebellar hemisphere have been removed on the right side. Other arteries in this illustration include the superior cerebellar, anterior inferior cerebellar, posterior inferior cerebellar, and anterior spinal arteries.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Li X, Zhang D, Zhao J. Anterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysms: six cases and a review of the literature. Neurosurgical review. 2012 Jan:35(1):111-9; discussion 119. doi: 10.1007/s10143-011-0338-1. Epub 2011 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 21748288]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDelion M, Dinomais M, Mercier P. Arteries and Veins of the Cerebellum. Cerebellum (London, England). 2017 Dec:16(5-6):880-912. doi: 10.1007/s12311-016-0828-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27766499]

Ogawa K, Suzuki Y, Takahashi K, Akimoto T, Kamei S, Soma M. Clinical Study of Seven Patients with Infarction in Territories of the Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2017 Mar:26(3):574-581. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.11.118. Epub 2016 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 27989483]

Tanaka M. Embryological Consideration of Dural AVFs in Relation to the Neural Crest and the Mesoderm. Neurointervention. 2019 Mar:14(1):9-16. doi: 10.5469/neuroint.2018.01095. Epub 2019 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 30827062]

Menshawi K, Mohr JP, Gutierrez J. A Functional Perspective on the Embryology and Anatomy of the Cerebral Blood Supply. Journal of stroke. 2015 May:17(2):144-58. doi: 10.5853/jos.2015.17.2.144. Epub 2015 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 26060802]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePekcevik Y. Double origin and early bifurcation of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery diagnosed by CT angiography. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2015 Nov:37(9):1141-3. doi: 10.1007/s00276-015-1453-4. Epub 2015 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 25732562]

Akhtar S, Azeem A, Jiwani A, Javed G. Aneurysm in the anterior inferior cerebellar artery-posterior inferior cerebellar artery variant: Case report and review of literature. International journal of surgery case reports. 2016:22():23-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.03.006. Epub 2016 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 27017276]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMascitelli JR, McNeill IT, Mocco J, Berenstein A, DeMattia J, Fifi JT. Ruptured distal AICA pseudoaneurysm presenting years after vestibular schwannoma resection and radiation. Journal of neurointerventional surgery. 2016 May:8(5):e19. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-011736.rep. Epub 2015 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 25964373]

Koizumi H, Kurata A, Suzuki S, Miyasaka Y, Tanaka C, Fujii K. Endosaccular embolization for a ruptured distal anterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysm. Radiology case reports. 2012:7(2):651. doi: 10.2484/rcr.v7i2.651. Epub 2015 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 27326283]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWillms JF, Baltsavias G, Burkhardt JK, Ernst S, Tarnutzer AA. Missed Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery Aneurysm Mimicking Vestibular Neuritis-Clues to Prevent Misdiagnosis. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2016 Dec:25(12):e231-e232. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.09.027. Epub 2016 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 27746081]

Tokimura H, Ishigami T, Yamahata H, Yonezawa H, Yokoyama S, Haruzono A, Obara S, Nishimuta Y, Nagayama T, Hirahara K, Kamezawa T, Sugata S, Arita K. Clinical presentation and treatment of distal anterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysms. Neurosurgical review. 2012 Oct:35(4):497-503; discussion 503-4. doi: 10.1007/s10143-012-0390-5. Epub 2012 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 22572778]

Sasame J, Nomura M. Dissecting Aneurysm of Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery Initially Presenting with Nonhemorrhagic Symptom. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2015 Aug:24(8):e197-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.03.055. Epub 2015 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 26015094]