Continuing Education Activity

Anterior mediastinal masses encompass a diverse group of neoplastic and nonneoplastic lesions located within the mediastinum, presenting a diagnostic challenge due to their varied etiologies and potential for serious complications. These masses can arise from thymic, germ cell, lymphoid, or thyroid tissues, among others. They may manifest with a wide range of clinical symptoms, including respiratory distress, chest pain, and superior vena cava syndrome. Diagnosis typically involves a combination of imaging modalities, tissue biopsies, and laboratory tests, with treatment strategies tailored to the specific underlying pathology, stage, and patient characteristics. Given the potential implications for patient outcomes, a multidisciplinary approach involving collaboration between clinicians, radiologists, pathologists, and other specialists is essential for accurate diagnosis, timely intervention, and optimal management of anterior mediastinal masses.

Participating in this course allows clinicians to deepen their understanding of anterior mediastinal masses, including their pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic evaluation, and management strategies. Additionally, clinicians can expect to enhance their clinical decision-making skills, refine their diagnostic reasoning abilities, and improve their capacity to collaborate effectively within multidisciplinary healthcare teams. By staying abreast of current evidence-based practices and emerging trends in anterior mediastinal mass management, participants will be better equipped to deliver high-quality, patient-centered care, optimize patient outcomes, and ensure patient safety in clinical practice.

Objectives:

Identify anterior mediastinal masses based on clinical presentation, imaging findings, and histopathological features.

Apply principles of multidisciplinary care to manage anterior mediastinal masses, involving surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, and other specialists.

Select appropriate tissue studies and laboratory tests to aid in diagnosing and characterizing anterior mediastinal masses.

Collaborate with multidisciplinary teams, including radiologists, pathologists, surgeons, oncologists, and nurses, to optimize patient care and outcomes.

Introduction

The mediastinum is located between the lungs and houses vital structures, including the thymus, heart, major blood vessels, lymph nodes, nerves, and portions of the esophagus and trachea. Anteriorly, the sternum bounds the mediastinum, while the thoracic vertebrae define the posterior border. Superiorly, it extends to the thoracic inlet, while the diaphragm forms its inferior boundary. Laterally, the mediastinum is delineated by the pericardial and mediastinal pleurae, encompassing critical thoracic organs and structures. Mediastinal tumors account for 3% of all the tumors that arise in the thoracic cavity.[1]

Comprising anterior, middle, and posterior compartments, mediastinal masses span a broad histopathological spectrum, with 50% occurring anteriorly. The most common anterior masses are often known by the 4T's: thymoma, teratoma, thyroid tissue, and 'terrible' lymphoma. These masses present unique challenges due to their proximity to critical thoracic structures. While imaging advancements aid characterization, accurate diagnosis often requires a multimodal approach integrating radiology, histology, and molecular techniques. Management considerations encompass histopathology, patient factors, and tumor biology. This article comprehensively reviews clinical presentation, diagnostic evaluation, and therapeutic interventions for anterior mediastinal masses, addressing recent advancements and controversies.

Etiology

The anterior mediastinum, positioned in front of the heart and bounded by the sternum, undergoes significant changes from childhood to adulthood. In children, the mediastinum houses the large thymus, a vital immune organ; in adults, it transitions to a smaller space as thymic function diminishes and the gland involutes. This evolution leaves behind an area susceptible to tumor formation. In addition to thymic tissue, the anterior mediastinum contains fat and lymph nodes, all corresponding with the most common etiologies of associated primary tumors. Although two-thirds of mediastinal masses are benign, about 59% of masses in the anterior compartment are malignant.[2] Predominantly, anterior mediastinal masses consist of epithelial tumors.

Thymoma, constituting less than 1% of adult malignancies, is the most commonly occurring anterior mediastinal mass in adults.[3] Benign masses of thymic origin are rare but include thymolipomas characterized by adipose composition and thymic cysts. Thymic cysts may be congenital, representing remnants of the thymopharyngeal duct, or acquired as a manifestation of an inflammatory neoplasm like Hodgkin lymphoma.[2] In contrast, thymic masses may occasionally manifest as aggressive and invasive neoplasms, such as thymic carcinoma and thymic carcinoid. Distinguishing these from thymic hyperplasia is crucial, with hyperplasia further classified into true and lymphoid (follicular) types. True thymic hyperplasia involves an enlarged thymus with the retained original shape and is often associated with stress-inducing factors like chemotherapy, burns, or corticosteroid administration. On the other hand, lymphoid thymic hyperplasia is characterized by an increased number of lymphoid follicles and is commonly linked to autoimmune conditions such as myasthenia gravis.[3] In rare instances, a thymic mass may be ectopic parathyroid tissue, adding to the complexity of differential diagnoses.

Germ cell tumors (GCTs) are characterized by primitive germ cells that fail to migrate entirely during embryonic development. While typically originating in the gonads, they represent 15% of anterior mediastinal masses.[2] Among GCTs, benign teratomas are most common, comprising tissues from at least 2 germ layers. Teratomas may contain ectodermic tissue, like hair and teeth, and tissues derived from mesoderm (bone) and endoderm (intestinal epithelium). If teratomas contain fetal or neuroendocrine tissue, they are classified as immature and malignant and carry a poor prognosis.[3] Seminomas and nonseminomatous GCTs (NSGCTs) are rare malignant GCTs, often presenting as large, bulky masses. Seminomas, representing 25% to 50% of malignant GCTs, may exhibit normal alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels but mildly elevated beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG).[3] Conversely, NSGCTs, comprising yolk sac tumors, embryonal carcinomas, choriocarcinomas, and mixed GCTs, are commonly associated with elevated AFP and β-hCG.

Primary mediastinal lymphomas represent approximately 10% of all mediastinal lymphomas.[3] Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) accounts for 50% to 70% of primary lymphomas and is classified into subtypes, including nodular sclerosing (the most common), lymphocyte-rich, lymphocyte-depleted, and mixed-cellularity. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) constitutes 15% to 25% of primary lymphomas, with the predominant types being primary mediastinal large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (PMBCL) and lymphoblastic non-Hodgkin lymphoma (LB-NHL), most commonly T-lymphoblastic lymphoma (TLL).[3][4]

Enlarged thyroid glands, or goiters, can occasionally manifest as anterior mediastinal masses. Substernal goiters, constituting a significant proportion, are characterized by at least 50% of their volume below the thoracic inlet. Typically, mediastinal goiters arise from the extension of lower cervical thyroid lobes into the thoracic inlet. In rarer cases, mediastinal goiters may result from remnants of embryonic tissues.[5] Ectopic thyroid tissue, defined as a location of thyroid tissue at a certain distance from the 2nd to 4th tracheal cartilages, resulting from an abnormality in embryological development or migration of the gland into the anterior mediastinum, accounts for 1% of all mediastinal masses.[6]

Less common origins of anterior mediastinal masses encompass parathyroid adenomas (approximately 20% are ectopic and can be found within the anterior mediastinum), hemangiomas, and sarcomas. Fibrosing mediastinitis, marked by the gradual infiltration of fibrous tissue, represents another uncommon etiology. This condition may arise from various sources, including infections like tuberculosis and histoplasmosis, as well as reactions to autoimmune disorders, medications, and radiation exposure.[7]

Epidemiology

The most frequent etiologies of anterior mediastinal masses are thymic malignancies in about 35% and lymphoma in about 25% (HL, 13% and NHL, 12%). Less common causes of anterior mediastinal masses are thyroid and other endocrine tumors (15%), benign teratoma (10%), malignant GCTs (10% with seminomas about 4% and NSGCT about 7%), and benign thymic lesions (5%).[8] When evaluating the epidemiology of anterior mediastinal masses, patient age and sex are the most important determinants.

For men and women older than 40, thyroid goiter and thymic malignancies represent two-thirds of anterior mediastinal masses. Between 30% to 50% of patients with thymomas will have an associated paraneoplastic syndrome, the most common of which is MG (30-50% of thymoma patients develop MG, while thymomas are discovered in 10-30% of MG patients), followed by hypogammaglobulinemia and pure red cell aplasia.[2][9][10] Notably, various autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus, polymyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, colitis, and myocarditis may also be associated with thymoma.[8][11]

The most common proportion of mediastinal masses in females aged 10 to 39 are lymphomas, typically HL and PMBCL.[8] Importantly, HL has a classic bimodal distribution of incidence, which peaks in young adulthood and older than 50. The next most common etiologies of anterior mediastinal masses in this population are thymic malignancies, often present in women older than 20, and benign teratomas, which are more prevalent in females younger than 25.[8]

In contrast, men 10 to 39 years, as well as children younger than 10, have no dominant tumor type of the anterior mediastinum.[3] The diagnosis of anterior mediastinal mass in these populations largely relies on the rapidity in which symptoms manifest, with a rapid onset of symptoms suggestive of LB-NHL, an intermediate onset HL or PMBCL, and a chronic onset of other tumors such as teratoma.[8]

Pathophysiology

Many patients with mediastinal masses may not exhibit any symptoms. However, the severity of symptoms can vary depending on factors such as the location of the mass and the extent of compression or invasion of nearby structures.[1] Compression or involvement of mediastinal structures by these masses can lead to a diverse range of symptoms, including cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, pain, dysphagia, stridor, hoarseness, facial swelling, arm swelling, hypotension due to cardiac compression, and neurologic changes such as Horner syndrome.

Additionally, systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and unexplained weight loss may be present, particularly in lymphoma cases or due to paraneoplastic syndromes, such as MG, associated with thymoma.[12] Furthermore, malignant tumors have the potential not only to compress or obstruct nearby structures but also invade them, leading to complications such as pneumonia, superior vena cava syndrome, broncho-esophageal fistula, pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, and various neurologic abnormalities.[12][13][14]

Histopathology

Mediastinal tumors pose significant challenges for surgical pathologists due to several factors. First, the diversity of lesions occurring in this location necessitates consideration of a broad range of differential diagnoses. Second, biopsies frequently yield small, fragmented specimens, further complicating interpretation. Third, pathologists with extensive experience in mediastinal pathology are relatively scarce due to the rarity of specimens from this region.[12]

Given the overlapping histologic features of many mediastinal tumors, a thorough evaluation of each specimen, often involving ancillary testing, is essential. Differential therapy approaches for various mediastinal tumors can significantly affect patient survival, underscoring the importance of accurate diagnosis. Furthermore, distinguishing whether a tumor originates from the mediastinum or adjacent lung or represents metastasis to the mediastinum is critical.

The following is the basic histology found in the most common tumors of the anterior mediastinum:

Thymomas

Thymomas exhibit a distinct lobulated architecture composed of cellular lobules containing neoplastic epithelial cells and reactive thymocytes intersected by fibrous bands. Many thymomas are encapsulated to some extent. The World Health Organization's (WHO) morphological classification of thymomas considers the shape of epithelial tumor cells, the tumor cell-to-thymocyte ratio, and cytologic atypia. Various growth patterns, such as microcystic changes, storiform growth, and staghorn-shaped vessels, can be observed, particularly in type A and AB thymomas or micronodular thymomas with lymphoid stroma. Prominent plasma cell infiltrates, microcystic patterns, and myoid cells (rhabdomyomatous thymoma) are also noted. Dilated perivascular spaces filled with plasma fluid, lymphocytes, and foamy macrophages are characteristic of type B1, B2, and B3 thymomas. Hassall corpuscles and a "starry-sky" pattern are additional histologic features seen in thymomas.[15]

Distinguishing between type B1 and B2 thymomas can be challenging. Type B1 thymomas contain areas of medullary differentiation without clustering of epithelial cells, while type B2 thymomas feature more clustered epithelial cells. Type B1 thymomas may resemble small lymphocytic lymphomas, but keratin stains aid in recognizing the epithelial meshwork. Type B3 thymomas, and occasionally type A or atypical A thymomas, may be confused with thymic carcinomas or metastatic squamous cell carcinomas due to distorted architecture. Thymomas can exhibit extensive cystic changes or be associated with thymic cysts.[15]

Germ Cell Tumors

Mediastinal GCTs have histology similar to those found in ovaries and testes.

Teratoma

- Mature: Mature tissue representing at least 2 embryonic layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, or endoderm). These are usually benign.

- Immature: Malignant GCT comprises cells from the 3 germ layers and contains variable amounts of mature and immature tissue (typically primitive neuroectodermal). Immature teratomas typically exhibit islands of poorly differentiated (primitive), immature, and blast-like cells. Among these cells, the neuroectodermal elements are often predominant and relatively easier to identify and quantify. Immature neuroectodermal tissues in immature teratomas include islets and nests of neuroblasts, hypercellular and mitotically active immature glia, and primitive, melanic pigmented retinal tissue. Additionally, benign vascular proliferations may occasionally accompany neural elements, which can sometimes lead to confusion with a vascular tumor.[16]

Seminoma

- Classic seminoma is characterized histologically by a clonal proliferation of neoplastic germ cells exhibiting distinct cytoplasmic borders, nuclei with prominent nucleoli, and angled ("squared-off") nuclear membranes. The cytoplasm often appears clear due to intracytoplasmic glycogen, giving the cells a "fried-egg" appearance at low magnification.

- Unlike other epithelial tumors such as embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, or choriocarcinoma, the neoplastic cells in seminoma are typically less cohesive. Additionally, clusters of lymphocytes are commonly observed in close association with the tumor cells.

Nonseminomatous

- Yolk sac tumors

- These exhibit significant morphological variability microscopically, for example, reticular or microcystic areas formed by a loose meshwork lined by flat or cuboidal cells; rounded glomeruloid bodies composed of a central blood vessel enveloped by tumor cells within a space that is also lined by tumor cells (Schiller-Duval body).[17] However, the significance of these patterns lies in their potential to complicate the recognition of yolk sac tumors.

- While hyaline-type globules and Schiller-Duval bodies are characteristic features of yolk sac tumors, they are only present in about 50% of cases. Typically, yolk sac tumors have a lower nuclear grade and may display edematous to the myxoid stroma, although these features are not invariably present.

- Embryonal carcinomas

- These exhibit multiple growth patterns, with the 3 most common being solid (55%), glandular (17%), and papillary (11%). Additionally, rare patterns such as nested (3%), micropapillary (2%), anastomosing glandular (1%), sieve-like glandular (<1%), pseudopapillary (<1%), and blastocyst-like (<1%) may be observed. The cells typically appear polygonal, with crowded arrangements, indistinct cell borders, and overlapping nuclei. They exhibit moderate amphophilic and granular cytoplasm and display pleomorphic, high-grade nuclear features. Mitotic figures are common, smudgy degenerative nuclei are often seen, and necrosis is present in single cells and larger foci.

- Embryonal carcinoma may grow admixed with yolk sac tumor and occasionally form polyembryoma-like structures known as embryoid bodies. Residual seminiferous tubules may contain germ cell neoplasia in situ or intratubular embryonal carcinoma, which can fill the tubule entirely. Lymphovascular invasion is common within embryonal carcinoma-predominant GCTs, often visualized at the periphery of the testicle and capable of occluding vessels, mimicking tumor nodules.

- Choriocarcinomas

- These typically present with solid nests, sheets of syncytial cells (syncytiotrophoblasts), and mononucleated trophoblasts (cytotrophoblasts and intermediate trophoblasts). Syncytiotrophoblasts are large, multinucleated cells with abundant, dense, eosinophilic cytoplasm and indistinct cell borders. They possess pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei that may exhibit a degenerated, smudged appearance. These cells often grow over mononucleated trophoblasts, forming either a thin compressed rim or a thicker cap. Mononucleated trophoblasts, comprising cytotrophoblasts and intermediate trophoblasts, are medium-sized cells with pale, eosinophilic cytoplasm and distinct cell borders. They are mitotically active.

- Choriocarcinoma commonly presents with hemorrhage, cyst formation, and necrosis. Lymphovascular invasion is often observed in tumors with a pure or predominant choriocarcinoma component. Germ cell neoplasia in situ may also be present. Nonneoplastic testicular parenchyma may exhibit various findings typical of other GCTs, including atrophy, maturation arrest, Leydig cell hyperplasia, microlithiasis, angiopathy, Sertoli cell-only tubules, and Sertoli cell nodules.

- Mixed GCTs

- Any combination of GCT types may be present in mixed tumors. The most common combinations are embryonal carcinoma and teratoma, followed by embryonal carcinoma and seminoma.

- Each type shows histologic features similar to those corresponding to the pure form.

Hodkin Lymphoma

The malignant cells found in HL are known as Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells, constituting only a small fraction (up to 10%) of the cellular infiltrate. These RS cells have a distinctive binucleate morphology with large inclusion-like nucleoli, often resembling owl's eyes. Variants of RS cells in HL may present as either mononuclear or multinuclear. The bi- or multinucleate appearance of RS cells is attributed to incomplete cytokinesis of mononuclear Hodgkin cells. The RS cells are in a mixed inflammatory cell background. Types of HL are listed below.

- Nodular sclerosis HL: RS cells may sometimes appear as a variant known as a lacunar cell. Dense collagenous bands divide the lymph node into nodules.

- Mixed cellularity HL: This type often presents with prominent eosinophils and can be confused with NHL.

- Lymphocyte-rich HL: This type is characterized by bizarre malignant cells, diffuse fibrosis, and necrosis.[18]

- Lymphocyte-depleted HL: This type has many lymphocytes and is nodular, and the RS cells express CD15 and CD30.

Non-Hodkin Lymphoma

- PMBCL: This type shows diffuse proliferation of medium- to large-sized lymphoid cells having moderate cytoplasm, irregular round or ovoid nuclei, and conspicuous nucleoli. A frequently reported feature is prominent cytoplasmic clearing present in this group of lymphomas.

- LB-NHL: This type shows diffuse sheets of medium-sized cells having round to irregular nuclei, inconspicuous to small nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm.[4]

Thyroid

Histologic subtypes of lesions in substernal goiter were papillary carcinoma (72.4%), follicular carcinoma (26.8%), and medullary carcinoma (0.8%).[19] The following are possible histologic features seen in substernal goiter or ectopic thyroid tissue that can be found in the anterior mediastinum:

- Variable-sized dilated follicles are flattened to hyperplastic epithelium.

- Nodules are present without a thick capsule.

- Nodules have variable histological patterns ranging from colloid and microfollicular to hypercellular/microfollicular.

- Secondary changes include foci of fresh or old hemorrhage, rupture of follicles with granulomatous response, fibrosis, calcification, and osseous metaplasia.

- Some cystically dilated follicles may exhibit papillary projections (known as Sanderson polsters) that can resemble papillary carcinoma but lack its nuclear features.

- If exposed to radioactive substances, cytologic atypia, particularly highly atypical nuclei, is present.

- There is a reduction and compression of the nonnodular thyroid tissue.

- There is a possibility of coexisting incidental papillary thyroid microcarcinoma.[20]

History and Physical

In evaluating anterior mediastinal masses, clinicians should conduct a thorough history and physical examination to identify symptoms and signs associated with these masses. Factors such as age and sex can aid in formulating a differential diagnosis, as the prevalence of mediastinal mass subtypes may vary among demographics. Reviewing the time course of symptom development or their absence can help narrow down potential diagnoses, considering that mediastinal processes may exhibit slow or rapid growth. Additionally, mediastinal masses might be associated with abnormalities in other body parts, necessitating a comprehensive review of systems during history-taking.

History

The diagnosis of anterior mediastinal mass may be an incidental finding in a patient who is asymptomatic; however, 60% of patients are symptomatic at presentation.[21] Inquire about symptoms such as cough, chest pain, dyspnea, voice changes (hoarseness), hemoptysis, and dysphagia, as these symptoms may indicate compression or invasion of surrounding structures. Constitutional symptoms like fever, night sweats, or unintentional weight loss (B symptoms) are classically observed in lymphoma but can also occur with other malignancies. Systemic complaints such as ptosis, dysphagia, weakness, abdominal pain, altered mental status, and fatigue can be manifestations of a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with an anterior mediastinal mass.

Assessing the rapidity of symptom onset is critical for determining the tumor's aggressiveness. Rapidly developing symptoms often indicate aggressive tumors like lymphoma or GCTs, whereas a more gradual onset may suggest slower-growing tumors such as thymomas or teratomas. Discuss any related medical conditions, such as previous malignancies, autoimmune disorders, or infections, that could provide clues to the etiology of the mediastinal mass. Also, document all current medications, including any immunosuppressive or hormonal therapies, noting allergies to medications or contrast agents for diagnostic imaging. Ask about a family history of cancer, autoimmune diseases, or genetic syndromes that might predispose the patient to mediastinal masses. Inquire about potential occupational or environmental exposures to toxins, radiation, or chemicals that could contribute to the development of mediastinal masses.

Physical Examination

The physical examination encompasses various aspects crucial for evaluating patients with anterior mediastinal masses—including assessing the patient's overall appearance for signs of distress or systemic illness, recording vital signs, and conducting specific examinations of different body systems. Each physical examination component provides valuable information to guide further diagnostic and management strategies for patients with anterior mediastinal masses.

Begin the exam by recording vital signs to assess for signs of infection or cardiovascular compromise. Assess the patient's appearance for signs of distress, cachexia (weight loss and muscle wasting), or pallor, which may indicate systemic illness. Look for lymphadenopathy, which may suggest metastatic spread or lymphoma. Evaluate the head and neck for proptosis, periorbital and facial edema, proptosis, facial plethora, and jugular venous distention, indicating superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome.[22] Auscultate the lungs for abnormal breath sounds, which could indicate underlying lung pathology or pleural effusion. Listen for abnormal heart sounds, murmurs, or pericardial rubs suggesting pericardial involvement or cardiac compression by the mediastinal mass. Palpate the abdomen for organomegaly or masses, as some anterior mediastinal masses can cause abdominal symptoms or be associated with metastases. Assess cranial nerves for signs of Horner syndrome (unilateral ptosis, miosis, anhidrosis) or other neurological deficits that may indicate neural structure involvement.[23] Check for peripheral edema, especially in the upper extremities and face, which can occur with SVC syndrome. Look for signs of dermatological conditions or cutaneous manifestations of systemic diseases that could be associated with the mediastinal mass. Perform a scrotal examination in males to assess for testicular masses, as some mediastinal tumors can be associated with GCTs. Notably, in men, gynecomastia may occur from the release of β-human chorionic gonadotropin, as is common with NSGCTs.[2]

Evaluation

The following tests should be obtained:

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory tests are important in diagnosing anterior mediastinal masses because they provide valuable information about the underlying pathology, guide further diagnostic evaluation, and inform treatment decisions. While laboratory tests alone may not provide a definitive diagnosis, they are essential adjuncts to clinical assessment and imaging studies.

- Complete blood count: This can reveal abnormalities such as anemia, leukocytosis, or leukopenia, which may suggest underlying hematological disorders or systemic inflammation associated with mediastinal masses.

- Comprehensive metabolic panel: This may identify electrolyte imbalances, liver or kidney dysfunction, or hypercalcemia, which can occur secondary to paraneoplastic syndromes or metabolic disturbances associated with certain mediastinal tumors.

- Tumor markers: Specific tumor markers may be elevated in certain mediastinal masses. For example:

- Alpha-fetoprotein: elevated in NSGCTs

- β-hCG: elevated in GCTs and choriocarcinomas

- Lactate dehydrogenase: less specific but usually increased with NSGCTs and lymphoma

- Carcinoembryonic antigen: elevated in thymic carcinomas

- Thyroid function tests: assesses thyroid function (especially if the mass is suspected to be a thyroid neoplasm or if there are symptoms suggestive of thyroid dysfunction)

- Inflammatory markers: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein may be elevated in cases of inflammation or infection associated with mediastinal masses.

- Autoimmune markers: Antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and other autoimmune markers may be assessed if there is suspicion of an underlying autoimmune disorder or paraneoplastic syndrome.

- Coagulation studies: Coagulation studies, including prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and fibrinogen levels, may be performed to assess for coagulopathies or thromboembolic events associated with mediastinal masses, especially those causing compression of vascular structures.

- Infectious serology: Serological tests for infectious agents such as Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and tuberculosis may be performed to identify underlying infectious etiologies contributing to mediastinal masses, particularly in cases presenting with systemic symptoms or suggestive clinical history.

- Miscellaneous: These are not always tested for but are recommended in certain cases.

- Thyroid carcinoid is associated with Cushing syndrome; therefore, the clinician should pursue a hypercortisolism workup in those cases.

- When suspecting a diagnosis of myasthenia gravis (MG), antibodies against acetylcholine receptors, muscle-specific kinase, and lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 are in order. Importantly, however, 10% to 15% of patients with clinical MG will be seronegative for commercially tested antibodies due to insufficiently sensitive tests or the presence of antibodies against other postsynaptic membrane antigens.[24]

- Gammaglobulins (eg, IgG, IgA, and IgM) can aid the diagnosis, as hypogammaglobulinemia is a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with thymoma.

Radiological Studies

Radiological studies play a crucial role in diagnosing anterior mediastinal masses by providing detailed anatomical information, assessing the extent of the mass, and guiding further management decisions. Several radiological modalities are commonly used or associated with the evaluation of these masses:

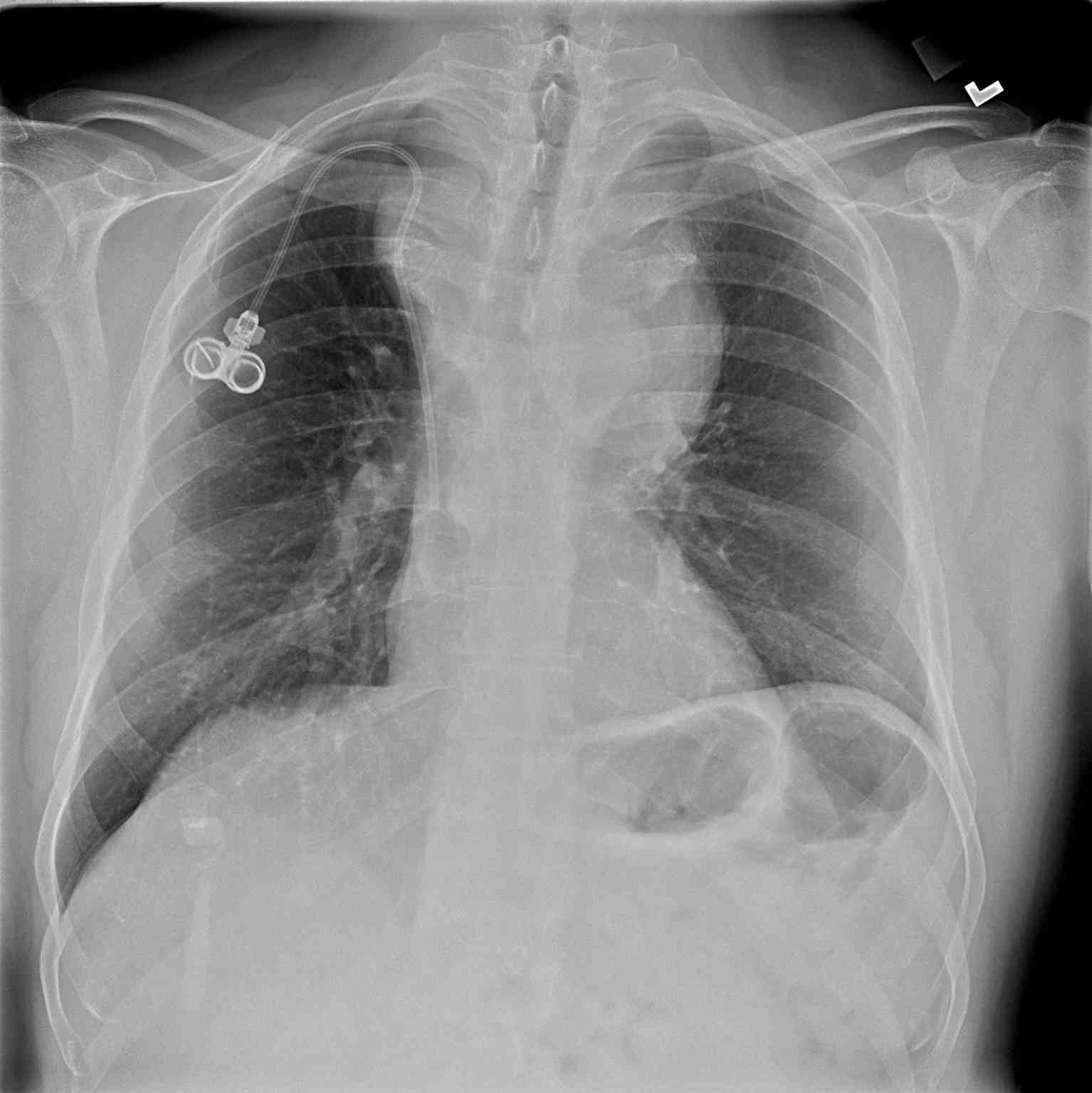

- Chest x-ray: A chest x-ray (CXR) is often the initial imaging study performed and may reveal the presence of a mediastinal mass, its location, size, and any associated pulmonary abnormalities. While CXR provides an overview, it lacks detailed mass characterization and may require further imaging for definitive diagnosis (see Image. Anterior Mediastinal Mass on Chest X-ray).

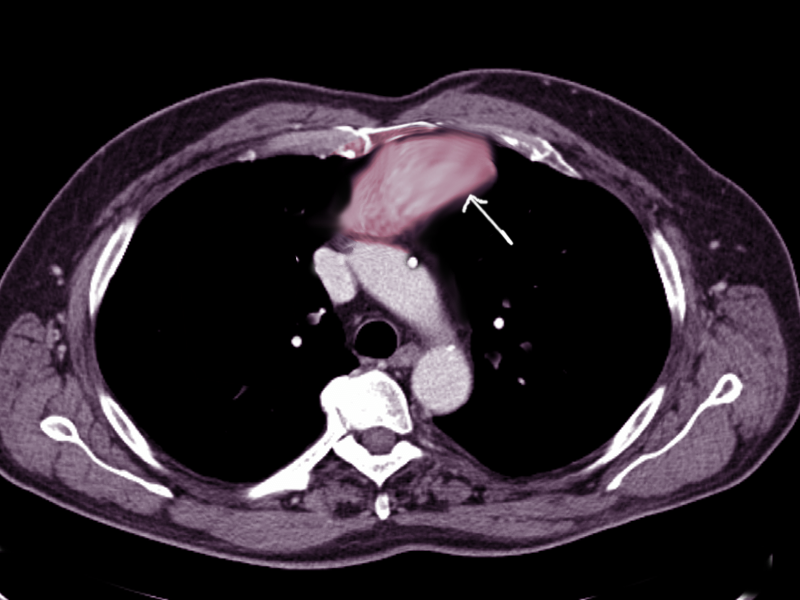

- Computed tomography scan: This imaging is the cornerstone for evaluating anterior mediastinal masses due to its high spatial resolution and ability to delineate soft tissue structures. Computed tomography (CT) scans can provide detailed information about the mass's size, location, morphology, density, and relationship to adjacent structures such as the heart, great vessels, and lungs (see Image. Anterior Mediastinal Mass on Chest Computed Tomography). Additionally, contrast-enhanced CT scans can help differentiate between solid and cystic components within the mass, assess vascular involvement, and detect metastases.[3] For example, a thymoma will appear as a slightly heterogeneous mass with smooth or lobular margins. At the same time, a teratoma is typically cystic and contains varying amounts of fat, soft tissue, and calcification. CT helps characterize lesions and aids with staging disease processes (eg, a mediastinal lymph node enlargement merits special attention). The presence of pleural or pericardial effusions also requires assessment, as this can clue the physician into the diagnosis of lymphoma or NSGCTs.[3]

- Magnetic resonance imaging: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is beneficial for evaluating mediastinal masses in cases where CT findings are equivocal or when soft tissue characterization is paramount. MRI provides excellent soft tissue contrast resolution and can help differentiate between various tissue types within the mass, such as fat, fluid, and solid components. One example is distinguishing thymic hyperplasia from thymic malignancy.[3] A thymic neoplasm may appear as a focal, nodular mass with a necrotic and calcified center, while thymic hyperplasia will be smooth and symmetric in morphology. Additionally, MRI helps confirm the presence of fat, which is more suggestive of thymic hyperplasia.[3] MRI is also especially valuable for assessing neural and vascular involvement, evaluating spinal cord compression, and detecting intraspinal extension of the mass.

- Positron emission tomography scan: Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, often performed in conjunction with CT (PET-CT), is valuable for assessing the metabolic activity of mediastinal masses and detecting distant metastases. PET-CT scans can help differentiate between benign and malignant lesions, guide biopsy or surgical planning, and monitor treatment response in patients with mediastinal malignancies. This is a valuable modality for staging lymphomas, as it is more accurate at detecting intranodal and extranodal disease than CT.[2]

- Ultrasound: While less commonly used for evaluating mediastinal masses, ultrasound (US) may be employed for initial assessment or guidance during biopsy procedures, particularly in pediatric patients or when radiation exposure needs to be minimized. The US can provide real-time visualization of the mass and adjacent structures, assess vascularity, and facilitate targeted sampling of suspicious lesions.

- Fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT: This imaging is sensitive for detecting hypermetabolic activity associated with malignant mediastinal masses and helps assess the mass's metabolic activity, identify areas of increased glucose metabolism suggestive of malignancy, and stage the disease by detecting distant metastases or lymph node involvement.

In addition to the standard radiological studies, specific imaging tests may be necessary for certain etiologies of anterior mediastinal masses to characterize the lesion and guide management decisions further:

- Scintigraphy with radioactive iodine: This imaging modality is valuable when evaluating a mediastinal goiter suspected of containing active thyroid tissue. Radioactive iodine uptake studies can help identify functioning thyroid tissue within the mass, aiding in diagnosing the retrosternal extension of a substernal goiter.

- Nuclear scans with isotopes, such as technetium-99: These are indicated when a mediastinal parathyroid adenoma is suspected. Technetium-99m sestamibi scintigraphy helps localize parathyroid adenomas, which may present as anterior mediastinal masses due to ectopic glandular tissue.

- Testicular US: All male patients with a mediastinal GCT should undergo testicular US as part of a comprehensive workup for primary gonadal malignancy. This test helps identify concurrent testicular lesions, assess the contralateral testis, and guide management decisions regarding testicular-sparing surgery or orchidectomy.

- Pulmonary function tests: These tests are essential for all patients with anterior mediastinal masses to assess lung function and identify any obstructive or restrictive pulmonary abnormalities. While spirometry is typically normal, pulmonary function tests may reveal a flattening of the inspiratory flow loop on the flow-volume curve in cases of variable extrathoracic obstruction caused by the mediastinal tumor. This finding can help evaluate the degree of airway compromise and guide preoperative assessment and postoperative management planning.

By incorporating these additional imaging modalities and tests into the diagnostic workup of anterior mediastinal masses, clinicians can obtain comprehensive information to diagnose the underlying pathology accurately, assess the extent of the disease, and optimize treatment strategies tailored to individual patients' needs.

Overall, the choice of radiological studies depends on the clinical presentation, suspected underlying pathology, and specific questions to be addressed. When interpreted in conjunction with clinical and histopathological data, radiological findings play a crucial role in establishing an accurate diagnosis, determining the extent of the disease, and guiding appropriate management strategies for patients with anterior mediastinal masses.

Tissue Studies

Tissue studies are crucial in diagnosing anterior mediastinal masses, providing histopathological confirmation of the underlying pathology, and guiding treatment decisions. Whenever obtaining diagnostic tissue, pathology should confirm that there is adequate tissue for examination. The rapid on-site cytological examination involves rapid tissue evaluation by pathology while the patient is still under procedural sedation so that additional tissue can be obtained if necessary, rather than submitting the patient for an added procedure.[25] Several tissue-based investigations may be required or associated with diagnosing these masses:

- Biopsy: Tissue biopsy is often the cornerstone of diagnosis for anterior mediastinal masses. Depending on the suspected etiology, biopsy techniques may include percutaneous needle biopsy, mediastinoscopy, thoracoscopy, or open surgical biopsy. A biopsy allows for histological examination of the mass, providing insights into its cellular composition, architecture, and degree of differentiation while helping differentiate between benign and malignant lesions and guiding subsequent management decisions, including selecting appropriate treatment modalities. However, in cases where the clinical presentation and radiographic features align with characteristic patterns, a tissue biopsy may not always be required to diagnose an anterior mediastinal mass. This scenario is often encountered with thymoma, teratoma, and thyroid goiter. For instance, in an adult 50 or older with MG and typical CT findings indicative of thymoma, a reliable diagnosis can often be established without the need for tissue biopsy. Needle biopsy of thymoma can prove to have adverse effects, such as tumor seeding, which case reports have described.[26]

- Histopathological examination: Histopathological analysis of biopsy specimens is essential for establishing a definitive diagnosis. Histological features observed on microscopic examination, such as cellular morphology, tissue architecture, mitotic activity, and necrosis, provide valuable information about the nature of the mass. Immunohistochemical staining may be employed to characterize cellular markers further and differentiate between different tumor subtypes or to confirm the presence of specific antigens associated with certain diseases.

- Molecular testing: Molecular studies, including genetic and molecular profiling, may be performed to identify specific genetic mutations, chromosomal abnormalities, or molecular biomarkers associated with particular tumor types. These tests can help refine the diagnosis, predict tumor behavior, and guide targeted therapies or personalized treatment approaches. Examples of molecular tests include fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), polymerase chain reaction, and next-generation sequencing.

- Flow cytometry: Flow cytometric analysis of tissue specimens, particularly in cases of lymphoproliferative disorders, can provide valuable information about the immunophenotypic characteristics of the cells comprising the mass. Flow cytometry helps identify cell surface markers, immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor gene rearrangements, and clonal populations of lymphoid cells, aiding in classifying and subtyping lymphomas and other hematologic malignancies.

- Cytogenetic studies: Cytogenetic analysis, including karyotyping and FISH, may be performed to detect chromosomal aberrations and genetic abnormalities associated with specific tumor types. These studies provide additional diagnostic and prognostic information and are particularly useful in diagnosing GCTs, thymomas, and certain hematologic malignancies.

Tissue studies are integral to diagnosing anterior mediastinal masses, offering valuable insights into these lesions' histological, molecular, and genetic characteristics. The findings from tissue-based investigations play a crucial role in formulating accurate diagnoses, guiding treatment decisions, and predicting patient outcomes.

Treatment / Management

The treatment and management of anterior mediastinal masses depend on various factors, including the specific etiology of the mass, its size, location, histological characteristics, and the patient's overall health status. Here's a focused discussion on the treatment of thymoma, GCTs, lymphoma, and substernal goiter:

Thymoma

- Surgical resection is the primary treatment modality for thymoma and is considered curative, especially in early-stage disease. Complete surgical excision with thymectomy is typically recommended, aiming for complete removal of the thymus and any surrounding tissue involved.

- Although usually benign, thymic cysts should be surgically excised because they may be microscopically identical to thymic neoplasms.[2]

- Thymic hyperplasia may be observed or resected when symptomatic, as in the cases of severe MG.

- Adjuvant therapies such as radiation therapy or chemotherapy may be considered in advanced-stage disease or where complete resection is not feasible.[2]

- In cases that are surgically resectable, induction chemotherapy before surgery, followed by consolidation chemotherapy and radiation after surgery, correlates with an improved 5-year survival rate of 95%. The typical induction regimen consists of 3 cycles of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, cisplatin, and prednisone, while the consolidation regimen incorporates 3 cycles of the same drugs at 80% of the doses.[27]

- For unresectable or metastatic thymoma, systemic chemotherapy, including regimens containing platinum-based agents or anthracyclines, may be used.

- In these cases, chemotherapy regimens consisting of cisplatin, vincristine, doxorubicin, and etoposide have resulted in a median survival period of 49 months.[28]

- Close surveillance with imaging studies is essential after treatment to monitor for disease recurrence or progression.

Germ Cell Tumors

- Treatment for GCTs in the anterior mediastinum typically involves a combination of surgical resection, chemotherapy, and sometimes radiation therapy. Seminomas are generally responsive to radiation therapy, but chemotherapy and surgical resection may also be indicated depending on the disease extent.

- Surgical resection is usually the initial step and aims for complete excision of the tumor. Teratomas are usually benign; resection is indicated when the lesions become symptomatic.

- Chemotherapy regimens, often based on cisplatin and etoposide, are commonly used both preoperatively and postoperatively to reduce tumor size, facilitate surgery, and eradicate micrometastases. NSGCTs receive a standard chemotherapy regimen of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin, followed by surgical resection if tumor markers normalize. Persistent elevation of tumor markers warrants salvage chemotherapy.

- Radiation therapy may be used as adjuvant therapy or for palliation in unresectable or residual disease cases.

- Long-term follow-up is crucial due to the risk of recurrence and the potential late effects of chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

Lymphoma

- Treatment strategies for anterior mediastinal HL and NHL involve a combination of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and, in some cases, targeted therapy or immunotherapy. The specific approach depends on factors such as the subtype of lymphoma, disease stage, patient age, and overall health status. Here's a discussion on the treatment of anterior mediastinal HL and NHL:

- HL

- Chemotherapy: The standard first-line treatment for HL is chemotherapy, typically with the ABVD regimen (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine).[2] This regimen is highly effective in inducing remission in most patients.

- Radiation therapy: Consolidative radiation therapy may be considered following chemotherapy, especially for bulky disease or residual masses after chemotherapy. Involved-site radiation therapy is preferred to minimize radiation exposure to surrounding normal tissues.

- Targeted therapy: In cases of relapsed or refractory HL, targeted therapies such as brentuximab vedotin (an anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate) or checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab or nivolumab may be used alone or in combination with chemotherapy.

- Bone marrow transplant: Patients with HL who relapse may benefit from a bone marrow transplant, with autologous being superior to allogeneic due to decreased mortality (27% versus 48%).[29]

- Stem cell transplantation: High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation may be considered for patients with relapsed or refractory disease or those at high risk of relapse.

- NHL

- Chemotherapy: Treatment of anterior mediastinal NHL typically involves chemotherapy regimens based on the subtype of lymphoma. For diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) is the standard first-line regimen. Specific chemotherapy regimens may be used for other NHL subtypes, such as primary mediastinal lymphoma (PMBCL) or T-lymphoblastic lymphoma.

- Radiation therapy: Radiation therapy may be utilized as consolidation therapy following chemotherapy for localized disease or as palliative treatment for symptomatic bulky masses.

- Targeted therapy and immunotherapy: In PMBCL, which often overexpresses the CD20 antigen, the addition of rituximab to chemotherapy has shown efficacy. For relapsed or refractory cases, novel agents such as the anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin or checkpoint inhibitors may be considered.

- Stem cell transplantation: In cases of relapsed or refractory disease or high-risk disease, autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplantation may be considered salvage therapy.

- Due to its propensity to involve the bone marrow and its high relapse rate, the treatment of LB-NHL consists of intensive chemotherapy with a maintenance phase chemotherapy. Additionally, patients with LB-NHL typically receive intrathecal chemotherapy and brain irradiation to prevent central nervous system relapse.[2] Patients with PMBCL usually have treatment with conventional chemotherapy and radiation. For both disease entities, a bone marrow transplant is indicated in cases of relapse with traditional therapy.

Substernal Goiter

- In most cases, the management of substernal goiter involves surgical resection to relieve symptoms, prevent complications, and confirm the diagnosis.

- Preoperative assessment with imaging studies such as CT or MRI helps determine the extent of substernal extension and plan the surgical approach.

- Thyroidectomy with removal of the substernal component is typically performed, often requiring a cervical collar incision combined with a median sternotomy or thoracotomy for adequate exposure.

- Thyroid hormone replacement therapy may be necessary postoperatively, especially if total thyroidectomy is performed.

- Close postoperative follow-up is essential to monitor for complications such as recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, hypoparathyroidism, or recurrence of substernal goiter.

In all cases, multidisciplinary management involving collaboration between surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, and other specialists is essential to optimize treatment outcomes and provide comprehensive care tailored to the patient's needs.

Differential Diagnosis

Anterior mediastinal masses can present with a wide range of differential diagnoses, reflecting the diverse structures and tissues within this anatomical region. Some common entities, excluding those previously discussed, included in the differential diagnosis of anterior mediastinal masses are:

- Lymphadenopathy

- Bronchogenic cyst

- Pericardial cyst

- Enteric cyst

- Thoracic aortic aneurysm

- Esophageal tumor

- Lymphangioma

- Neurogenic tumor

- Meningocele

- Thoracic spine lesion

- Metastatic lesion

- Aortic aneurysm

- Infection (eg, tuberculosis or fungal)

- Inflammatory condition (eg, sarcoidosis)

- Parathyroid adenoma

Given the wide range of potential etiologies, evaluating anterior mediastinal masses requires a comprehensive approach, often including a combination of clinical, radiological, and pathological assessments to establish an accurate diagnosis and guide appropriate management.

Staging

The following are the staging systems used for the most common primary malignancies seen in the anterior mediastinum:

Thymoma Staging

Thymoma staging typically follows the Masaoka-Koga staging system, which is widely used to determine the extent of thymoma spread.[30] This staging system is based on the tumor's local invasiveness and the presence or absence of distant metastasis. Here is an overview of this system:

Masaoka-Koga Staging System

- Stage I

- In Stage I, the thymoma is encapsulated and confined within the thymus gland.

- There is no invasion into surrounding tissues.

- Stage II

- Stage II involves microscopically invasive thymoma.

- Although the tumor may have microscopic extensions into the capsule, it is still primarily confined within the thymus gland.

- Stage III

- Stage III is characterized by macroscopic invasion into surrounding tissues or organs.

- The tumor may invade nearby structures such as the pericardium, pleura, or lung.

- Stage IVA

- Stage IVA indicates the presence of pleural or pericardial metastases.

- These metastases may be microscopic or macroscopic.

- Stage IVB

- Stage IVB thymoma has distant metastases.

- These metastases may be found in the liver, bones, or other organs.

The World Health Organization's classification of thymic epithelial tumors also plays a role in staging and determining prognosis. This classification system includes various histological types and grades of thymic tumors, which can further inform treatment decisions and prognosis.

Accurate staging of thymoma often requires a combination of imaging studies (such as CT scans and MRI) and histopathological evaluation of tissue samples obtained through biopsy or surgical resection. Treatment decisions, including surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or a combination of these modalities, are usually tailored based on the stage of the disease and other factors, such as the patient's overall health and preferences.

Regular follow-up and monitoring are crucial for patients with thymoma, as recurrence can occur even after successful treatment. Collaboration between oncologists, surgeons, radiologists, and other specialists is essential to provide comprehensive care for individuals with thymic tumors.

HL Staging

The Ann Arbor staging system and the Cotswold modification are 2 widely used systems for staging HL. They provide a standardized way of describing the extent of the disease, which helps guide treatment decisions and predict prognosis. The Cotswold modification is an update to the Ann Arbor system, incorporating additional information to better reflect disease characteristics. Here is an overview of both systems and how they relate:

Ann Arbor Staging System:

- Stage I: This includes involving a single lymph node region (I) or extralymphatic site without nodal involvement (IE).

- Stage II: This stage involves 2 or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm (II). This can also include localized involvement of a single extralymphatic organ or site plus regional lymph node involvement (IIE).

- Stage III: Stage III involves the diaphragm's lymph node regions on both sides, potentially with localized extralymphatic extension (III). No systemic symptoms are present in Stage III.

- Stage IV: In this stage, one or more extra lymphatic organs or tissues are involved diffusely or disseminated, with or without associated lymph node involvement. Stage IV disease may include bone marrow involvement or liver or lung infiltration.

The Cotswold modification extends the Ann Arbor system by further classifying stage II disease based on the presence or absence of specific risk factors:

Cotswold Modification:

- A and B symptoms:

- A: Absence of systemic symptoms (fever, night sweats, weight loss)

- B: Presence of systemic symptoms

- E designation: Indicates extranodal extension of the tumor

- S designation: Indicates involvement of the splenic region

- X designation: Indicates bulky disease (defined as a mediastinal mass with a diameter of one-third or more of the internal thoracic diameter on a standard CXR or a mass of any size on a CT scan)

While the Cotswold modification adds complexity to the staging process, it provides valuable information for helping clinicians determine the appropriate treatment approach and predict patient outcomes. Both the Ann Arbor system and the Cotswold modification continue to be widely used in the staging of HL, contributing to standardized reporting and improved patient care.

NHL Staging

Staging of NHL of the anterior mediastinum typically follows the Ann Arbor staging system with the Cotswold modification as described above.

Germ Cell Tumor Staging

Staging for anterior mediastinal GCTs often involves a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and pathological assessment. While no specific staging system is dedicated solely to anterior mediastinal GCTs, these tumors may be staged using a modified version of the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) system, similar to other extragonadal GCTs.

TNM System

- T stage (primary tumor)

- TX: Primary tumor cannot be assessed

- T0: No evidence of primary tumor

- T1: Tumor confined to the mediastinum

- T2: Tumor invades adjacent structures within mediastinum (eg, pleura, pericardium)

- T3: Tumor invades beyond the mediastinum (eg, lung, chest wall)

- T4: Tumor invades distant organs or tissues

- N stage (regional lymph nodes):

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

- N0: No regional lymph node metastasis

- N1: Metastasis to regional lymph nodes

- M stage (distant metastasis):

- MX: Distant metastasis cannot be assessed

- M0: No distant metastasis

- M1: Distant metastasis present

Prognosis

The prognosis of anterior mediastinal masses varies widely depending on several factors, including the specific histopathological diagnosis, presentation stage, treatment response, and individual patient characteristics. Here is a brief overview of the prognosis for some common anterior mediastinal masses:

Thymoma

The prognosis of thymomas is primarily determined by complete surgical resection (R0 resection), which is the factor most strongly associated with favorable outcomes.[3] The Masaoka-Koga staging system is commonly used to estimate 5-year survival rates, with encapsulated tumors (stage I) demonstrating the best prognosis, typically achieving 5-year survival rates of 96% to 100%. In contrast, metastatic disease (stages IVA and IVB) is associated with the poorest prognosis, with 5-year survival rates ranging from 11% to 50%.[2] Other factors predictive of poor prognosis include tumor size exceeding 10 cm, patient age younger than 30, evidence of tracheal or vascular compression, epithelial or mixed histology, and the presence of paraneoplastic syndromes.[2]

Unlike thymomas, thymic carcinoma and carcinoid tumors are characterized by a much poorer prognosis, and therefore, the Masaoka-Koga staging system is less informative in predicting outcomes for these malignancies. Cytologic features indicative of a worse prognosis include high-grade atypia, necrosis within the tumor, and a high mitotic rate exceeding 10 mitoses per high-power field.[2]

Germ Cell Tumors

Regarding GCTs, teratomas have the best prognosis, as most are benign. Seminomas and NSGCTs have a poorer prognosis and have 5-year survival rates of 86% and 48%, respectively. Persistently elevated tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein and β-hCG) after chemotherapy are associated with worse outcomes.[2]

Lymphoma

Patients classified as stage I or II for HL have a favorable prognosis, with greater than 90% cure rates with standard treatment. Stage IIIA and IIIB have cure rates of 60% to 70%. Stage IV disease carries the worst prognosis, with a cure rate of 50% to 60%. Poor prognostic factors for HL include the following at diagnosis: male sex, age greater than 45, serum albumin less than 4 g/dL, hemoglobin less than 10.5 g/dL, and white blood cell count greater than or equal to 15,000 cells/μL, and lymphocyte count of less than 600 cells/μL.[31]

Other Masses

Other anterior mediastinal masses, such as substernal goiters or neurogenic tumors, may have variable prognoses depending on tumor size, invasiveness, and histology. Generally, benign masses may have a better prognosis than malignant tumors, particularly if they can be resected entirely without complications.

Complications

Anterior mediastinal masses can lead to various complications due to their location and potential effects on adjacent structures. Here are some common complications associated with these masses:

- Compression of adjacent structures: One of the most significant complications of anterior mediastinal masses is compression of nearby structures, including the trachea, bronchi, esophagus, and major blood vessels such as the SVC. Compression can lead to symptoms such as dyspnea, cough, stridor, dysphagia, and SVC syndrome, characterized by facial swelling, upper limb edema, and distended neck veins.

- Respiratory compromise: Mass effects on the trachea or bronchi can result in airway obstruction, leading to respiratory distress and potentially life-threatening respiratory failure. Severe compression of the airways may require urgent intervention, such as tracheostomy, bronchoscopic stenting, or surgical decompression. Large mediastinal masses can cause pleural effusion or pneumothorax due to compression or invasion of the pleural space. These may lead to respiratory compromise and require drainage for symptomatic relief.

- Cardiovascular complications: Compression of the SVC or adjacent cardiac structures can impair venous return and cardiac function, leading to symptoms of SVC syndrome, including facial edema, jugular venous distention, and potentially cardiac tamponade in severe cases. Cardiac compression may also cause arrhythmias or hemodynamic instability. Invasive anterior mediastinal masses may lead to pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade due to direct extension into the pericardial space. Cardiac tamponade presents as dyspnea, hypotension, and jugular venous distention and requires emergent pericardiocentesis for decompression.

- Neurological complications: Anterior mediastinal masses can compress or invade neural structures, resulting in neurological deficits such as Horner syndrome (ptosis, miosis, anhidrosis), brachial plexopathy, or spinal cord compression. These complications may manifest as weakness, sensory changes, or loss of reflexes in the upper limbs.

- Malignant transformation and metastasis: Some anterior mediastinal masses, such as thymomas or GCTs, have the potential for malignant transformation or metastasis to distant sites. Metastatic spread may lead to secondary tumors in other organs, further complicating the management and prognosis of the disease.

- Endocrine dysfunction: Anterior mediastinal masses originating from the thymus or thyroid gland may disrupt normal endocrine function, leading to hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism. These complications may require hormone replacement therapy or other interventions to manage.

Overall, the complications of anterior mediastinal masses can vary depending on the underlying pathology, tumor size, location, and invasiveness. Prompt recognition and management of these complications are essential to prevent morbidity and improve patient outcomes. A multidisciplinary approach involving thoracic surgeons, oncologists, interventional radiologists, and other specialists is often necessary for comprehensive management.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients diagnosed with anterior mediastinal masses require comprehensive education about their specific disease process, available treatment options, and the anticipated prognosis. Empowering patients with knowledge about their condition enables them to participate actively in care decision-making. The importance of consistent follow-up appointments to monitor response to treatment and detect any signs of disease relapse early must be emphasized. By engaging patients in their healthcare journey, healthcare providers can enhance patient understanding, improve treatment adherence, and ultimately optimize patient outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of anterior mediastinal masses requires a collaborative approach involving physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals to ensure patient-centered care, optimize outcomes, enhance patient safety, and improve team performance. Physicians and advanced practitioners use their clinical expertise to diagnose and develop treatment plans tailored to individual patient needs, considering tumor type, stage, and patient preferences. They employ practical communication skills to educate patients about their condition, treatment options, and potential outcomes, fostering shared decision-making and empowering patients to actively participate in their care journey.

Nurses are vital in providing comprehensive patient care, emotional support, symptom management, and care coordination across settings. They facilitate interprofessional communication by relaying patient updates, coordinating consultations, and ensuring continuity of care throughout the treatment process. Pharmacists contribute by reviewing medication regimens, identifying potential drug interactions, and providing medication counseling to optimize therapeutic outcomes and minimize adverse effects. Collaborative team-based care involves regular multidisciplinary meetings where healthcare professionals discuss patient cases, share insights, and collectively develop strategies to enhance care coordination, improve patient outcomes, and ensure patient safety. By leveraging their collective skills, expertise, and collaborative efforts, healthcare teams can provide holistic, patient-centered care that addresses the complex needs of patients with anterior mediastinal masses, ultimately leading to improved clinical outcomes and enhanced overall quality of care.