Continuing Education Activity

Takayasu arteritis (pulseless disease) is a systemic inflammatory condition characterized by damage to the large and medium arteries and their branches. It presents at first with nonspecific constitutional symptoms such as fever, malaise, weight loss, and anorexia. Other presentations such as hypertension, neurologic manifestations, and upper limb claudication occur secondary to arterial insufficiency. This activity illustrates the evaluation and management of Takayasu arteritis and explains the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Explain the epidemiology of Takayasu arteritis.

- Describe the pathophysiology of Takayasu arteritis.

- Outline the use of CTA in the evaluation of Takayasu arteritis.

- Review the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to provide patient education and long term monitoring of the effects of drugs which will improve outcomes for patients affected by Takayasu arteritis.

Introduction

Takayasu arteritis, aka pulseless disease, is a systemic inflammatory condition which leads to damage of the medium and large arteries and their branches. It occurs predominantly in young Asian women. It usually involves the aorta and its major branches, particularly the renal arteries, carotid arteries, and subclavian arteries, and leads to stenosis, occlusions, or aneurysmal degeneration of these large arteries. An abnormality in cell-mediated immunity seems to be its main pathogenesis, but its etiology is still largely unknown. Diagnosis is based on suspicion as well arteriographic findings. Treatment usually begins with medical management using corticosteroids; however, surgical management has become more common recently due to findings of an overall lack of disease regression and high rates of relapse with just medical management alone.

Etiology

The etiology of Takayasu arteritis is largely unknown. At its core, it is an inflammatory disease, and it is thought that autoimmune cell-mediated immunity may be responsible for the disease. Eventual transmural fibrous thickening of the arterial walls is what ultimately leads to ischemic changes and formation of alternating areas of pseudoaneurysm.

Epidemiology

Takayasu arteritis is a rare disease, with a reported worldwide incidence rate of only 1 to 2 per million, the majority being in females (9:1). It is considered a disease of the young, with most being found in patients 40 to 50 years of age[1]. However, it has also been described in young children and the elderly. It is mostly found in patients of Asian or Mexican descent and is rare in North America.

Pathophysiology

There continues to be a substantial lack of understanding of the pathogenesis of Takayasu arteritis, and the etiology is largely unknown. At its core it is characterized as an inflammatory granulomatous vasculitis of medium and large arteries, which leads to transmural fibrous thickening of the arterial walls, leading to multiple vascular obstructions and eventual ischemic changes[2]. Degeneration of elastic fibers is also a feature, with the formation of aneurysms occurring when inflammation leads to loss of medial smooth muscle cells. Cell-mediated immunity involving CD4+ and CD8+ T cells may play a key role in the pathophysiology of Takayasu arteritis, as these cells support the formation of granulomas and potentially activate the activities of various proteases such as matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), as well as other cells which promote chronic inflammation and fibrosis formation. There has also been speculation about a potential link with certain human leukocyte antigens (HLA), although this has not fully been clarified.

Histopathology

Biopsy specimens are a rarely available for Takayasu arteritis but are most common in the unusual case of a potential biopsy of an excised segment, or from an autopsy. Inflammation targets areas around the vasa vasora and at the medio-adventitial junction. Mononuclear cell infiltration is common, and giant cell granulomatous reaction may be present. Reactive fibrosis and increased ground substance in the intima may also be present. In the aorta specifically, the arterial walls will feel extraordinarily stiff and rigid if palpated, with often strikingly high degrees of adventitial and periadventitial fibrosis.

History and Physical

Constitutional symptoms characterize a very nonspecific early acute inflammatory phase seen in Takayasu arteritis which includes fever, malaise, muscle aches, weight loss, and anorexia. Most patients do not seek treatment until signs of the “pulseless” phase occur, in which symptoms are usually secondary to arterial insufficiencies; these include hypertension in renovascular stenosis, neurologic manifestations as seen with carotid artery occlusion, or upper limb claudication as seen in upper extremity ischemia secondary to stenosis. Thus, delayed diagnosis is quite common. Severe debilitating upper or lower extremity ischemia often leads to diminished or absent pulses, hence the name "pulseless disease," or possibly a vascular bruit. Other potential late findings worth noting include accelerated atherosclerosis or heart failure.

Evaluation

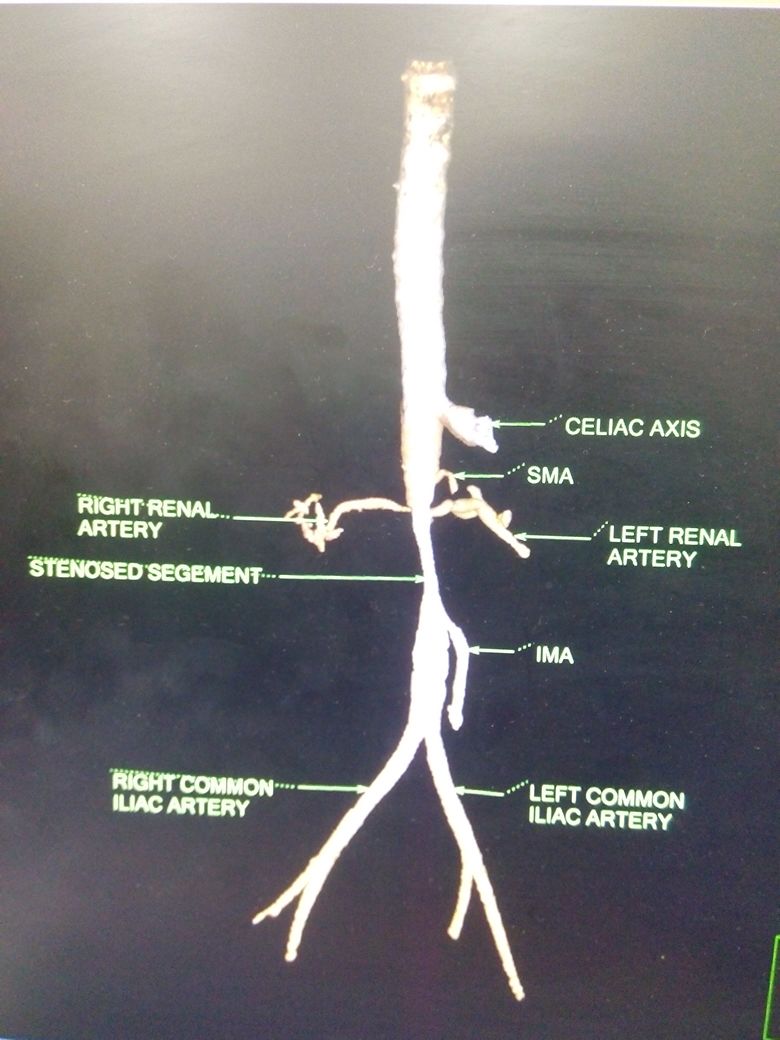

Clinical suspicion is needed to diagnose Takayasu arteritis, and thus a good, complete history and physical exam is a necessity. Imaging is vital, and CTA has recently become the standard for initial staging of disease distribution (previously it was conventional angiography) in Takayasu arteritis. This standard is based on the 1994 Tokyo International Conference Classification of Takayasu arteritis. CTA will allow for visualization of vessel wall thickening and luminal narrowing. MRI and MRA may also be used for identification and provide excellent multiplanar imaging without ionizing radiation use. However, like with all MRA, it tends to overestimate the degree if stenotic disease and access to MRI or MRA are much more difficult.

Treatment / Management

Initial treatment of symptomatic Takayasu arteritis begins with corticosteroids. Immunosuppressive medications have also been used in place, or in combination with corticosteroids. However, studies have not conferred an overall advantage of these medications.

The benefits of revascularization for these conditions are well recognized, but the uncertainty of this disease process had tempered enthusiasm for primary surgical approaches. Thus, traditionally, surgical therapy had been reserved for symptomatic manifestations of arterial occlusive disease refractory to corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressive therapy. However, this experience seems to be changing recently as the efficacy and ability of medical management to arrest disease has been called into question. A recent nationwide study revealed that 50% of patients with Takayasu arteritis will relapse and experience a vascular complication less than 10 years from diagnosis. Those most likely to relapse include males and those with elevated C-reactive protein.

Surgical revascularization is now rapidly evolving into a primary treatment choice. Transluminal angioplasty has been studied in the past. However, its overall role is limited in the treatment of patients with Takayasu arteritis. The fibrous nature of the arterial obliteration mitigates any durable long-term benefit[3]. A study at the Cleveland Clinic revealed 78% of their patient cohort treated with angioplasty in various anatomic locations experienced restenosis during a median 3-year follow-up, and 93% required reintervention at some point. Thus, PTA should be viewed a short-term strategy for symptomatic relief if other medical needs must be attended to first in a given patient.

Arterial reconstruction is the other surgical option in patients with Takayasu arteritis. The type of reconstruction depends on where known lesions lie, as well as the patient’s surgical anatomy. In general, Dacron or polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) would be used for major aortic reconstructions, while autogenous saphenous vein would be used for extremity or isolated renal or mesenteric revascularization. Caution should be used when using autogenous saphenous vein secondary to its known propensity for aneurysmal degeneration. It is important that both proximal and distal anastomotic sites are free of any inflammatory involvement. Anastomosis onto involved arterial segments is a setup for early graft failure. In a study of 40 patients with TA at the University of Southern California, renovascular procedures were most common[4]. Other procedures included various aortic reconstructions, aorta-carotid bypasses for cerebrovascular insufficiency, and bypasses to distal subclavian, axillary, or brachial arteries for upper extremity ischemia.

Surgical therapy is usually well tolerated due to the young age of most patients with Takayasu arteritis. Most have dramatic improvements in their symptoms following surgery, whether it be decreases, or even curing, of hypertension following renovascular reconstruction, or resolving of upper limb ischemia following upper extremity bypass for example. These findings suggest that surgical correction of symptomatic Takayasu arteritis will continue to rise.[5][6][7][8]

Differential Diagnosis

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

TA is a complex vascular disorder that has no cure. It is best managed with an interprofessional team that includes a vascular surgeon, radiologist, cardiologist, internist, neurologist, and nephrologist. A nurse should provide assistance with and coordination of patient education. While isolated lesions may be stented, long lesions may require a bypass. Some patients may benefit from steroids and other immunosuppressive agents. These patients will need long term monitoring for adverse side effects of the drugs by the nurse practitioner and primary care provider. The prognosis of patients with TA is guarded.[9][10]