Continuing Education Activity

Ascites is the pathologic accumulation of fluid within the peritoneal cavity. It is the most common complication of cirrhosis and occurs in about 50% of patient with decompensated cirrhosis in 10 years. The development of ascites denotes the transition from compensated to decompensated cirrhosis. Mortality increases from complications such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome. Mortality ranges from 15% in a year to 44% in 5 years. This activity describes the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of ascites and highlights the role of team-based interprofessional care for affected patients.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of ascites.

- Review the workup of a patient with ascites.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for ascites.

- Describe interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination in the evaluation and treatment of ascites to improve outcomes.

Introduction

Ascites is the pathologic accumulation of fluid within the peritoneal cavity. It is the most common complication of cirrhosis and occurs in about 50% of patient with decompensated cirrhosis in 10 years. The development of ascites denotes the transition from compensated to decompensated cirrhosis. Mortality increases from complications such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome. Mortality ranges from 15% in a year to 44% in 5 years.[1][2][3]

In most healthy individuals, there is very little free intraperitoneal fluid; some women may have about 20 ml during the menstrual cycle.

Etiology

In the United States, the most common disease that causes patients to get ascites is cirrhosis, which accounts for approximately 80% of cases. Other causes of ascites include cancer, 10%; heart failure, 3%; tuberculosis, 2%; dialysis, 1%; pancreatic disease, 1%; and others, 2%. Up to 19% of patients with cirrhosis will have hemorrhagic ascites; this may develop spontaneously with 72% of the cases most likely due to bloody lymph and 13% due to hepatocellular carcinoma. It can also develop following paracentesis.[4][5]

Other causes of asictes include:

- Chronic alcohol use

- IV drug use

- Obesity

- Hypercholesterolemia

- Type 2 diabetes

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Severe malnutrition

- Pancreatic ascites

- Ovarian lesions

Epidemiology

Patients with cirrhotic ascites have a 3-year mortality rate of approximately 50%. Refractory ascites carries a poor prognosis, with a 1-year survival rate of less than 50%. Males have little intraperitoneal fluid, females have approximately 20 mL, depending on the phase of their menstrual cycle.

Pathophysiology

The first abnormality that develops is portal hypertension in the case of cirrhosis. Portal pressure increases above a critical threshold and circulating nitric oxide levels increase, leading to vasodilatation. As the state of vasodilatation becomes worse, the plasma levels of vasoconstrictor sodium-retentive hormones elevate, renal function declines, and ascitic fluid forms, resulting in hepatic decompensation.

Through the production of proteinous fluid by tumor cells lining the peritoneum, peritoneal carcinomatosis also can cause ascites. In high-output or low-output heart failure or nephrotic syndrome, effective arterial blood volume is decreased, and the vasopressin, renin-aldosterone, and sympathetic nervous systems are activated, leading to renal vasoconstriction and sodium and water retention.[6]

History and Physical

Patients typically report progressive abdominal distension that may be painless or associated with abdominal discomfort, weight gain, early satiety, shortness of breath, and dyspnea resulting from fluid accumulation and increased abdominal pressure. Symptoms such as fever, abdominal tenderness, and confusion can be seen in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Patients with malignant ascites can have symptoms related to malignancy, which may include weight loss. On the other hand, patients with ascites due to heart failure may report dyspnea, orthopnea, and peripheral edema, and those with chylous ascites report diarrhea, steatorrhea, malnutrition, edema, nausea, enlarged lymph nodes, early satiety, fevers, and night sweats.

Patients with ascites typically will have flank dullness on examination, shifting dullness, a fluid wave, evidence of pleural effusions, and findings related to the underlying cause of the ascites, such as stigmata of cirrhosis (cirrhosis includes spider angioma, palmar erythema, and abdominal wall collaterals.

Spider angiomata, jaundice, muscle wasting, gynecomastia, and leukonychia are present in patients with advanced liver disease.

An umbilical nodule that is not bowel or omental, such as a Sister Mary Joseph nodule, provides evidence for cancer as the cause of ascites. In heart failure, physical examination findings may include jugular venous distension, pulmonary congestion, or peripheral edema.

Evaluation

Diagnostic abdominal paracentesis with the appropriate ascitic fluid analysis is probably the most rapid and cost-effective method of diagnosing the cause of ascites.[7][8]

The initial tests that should be performed on the ascitic fluid include a blood cell count, with both a total nucleated cell count and polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) count, and a bacterial culture by bedside inoculation of blood culture bottles.

Ascitic fluid protein and albumin are measured simultaneously with the serum albumin level to calculate the serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG).

The presence of a gradient greater or equal to 1.1 g/dL (greater or equal to 11 g/L) predicts that the patient has portal hypertension with 97% accuracy. This is seen in cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis, heart failure, massive hepatic metastases, heart failure/pericarditis, Budd-Chiari syndrome, portal vein thrombosis, and idiopathic portal fibrosis. A gradient less than 1.1 g/dL (less than 11 g/L) indicates that the patient does not have portal hypertension and occurs in peritoneal carcinomatosis, peritoneal tuberculosis, pancreatitis, serositis, and nephrotic syndrome.

Additional tests may be performed only if a specific diagnosis is suspected clinically. LDH and glucose level should be determined in suspected cases of secondary peritonitis. Other tests to consider include amylase (greater than 1000 U/L suggests pancreatic ascites). Mycobacterial culture should be performed only if tuberculosis is strongly suspected. Other ascitic fluid indices such as lactate and pH offer little to no additional information.

Chest x-ray may reveal elevated diaphragm.

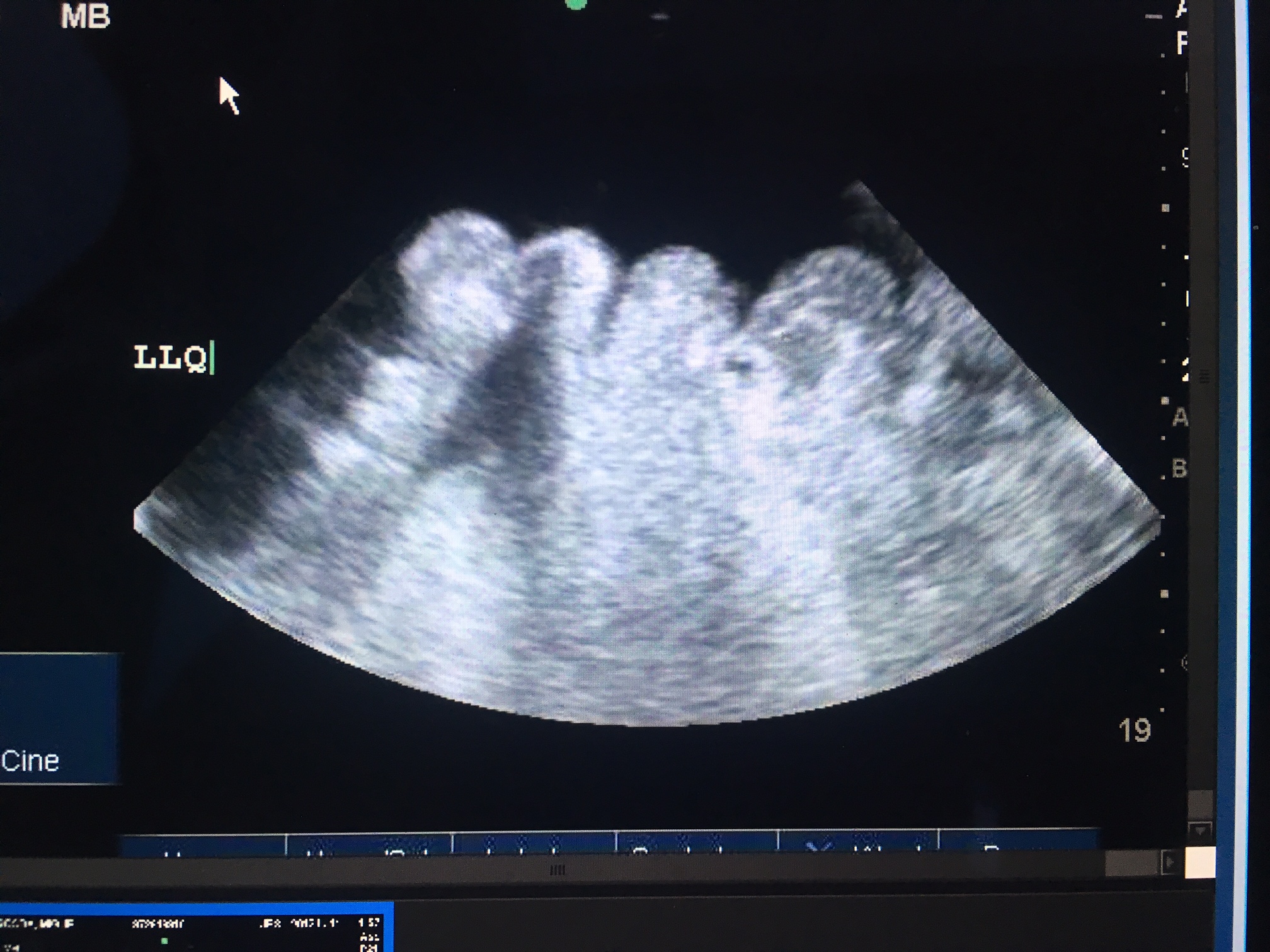

Ultrasound is the most sensitive test to detect ascites. It will reveal homogenous freely mobile anechoic collection in the peritoneal cavity. The smallest amount of fluid is usually seen in Morison pouch.

CT scan can also be used to detect ascites and may also help determine for presence of any masses.

Treatment / Management

Appropriate treatment of ascites depends on the cause of fluid retention. The goals of therapy in patients with ascites are to minimize the ascitic fluid volume and decrease peripheral edema, without causing intravascular volume depletion.[9][10][11]

Sodium restriction and diuretics form the basis of treatment

In cases of high-albumin-gradient ascites which occurs in cirrhosis, the treatment of ascites in these patients includes abstinence from alcohol, restricting dietary sodium to 88 mEq (2000 mg) per day, and treating with diuretics (spironolactone and furosemide in a ratio of 100:40 mg/day)

Patient with a treatable liver condition, such as autoimmune hepatitis, chronic hepatitis B with reactivation, hemochromatosis, or Wilson disease, should receive specific therapy for these diseases. Occasionally, cirrhosis due to causes other than alcohol or hepatitis B is reversible; however, these diseases are usually less reversible than in alcoholic liver disease, and by the time ascites is present, these patients may be better candidates for liver transplantation than for protracted medical therapy.

Low-albumin-gradient ascites commonly occurs in non-ovarian peritoneal carcinomatosis. These patients often benefit from an outpatient therapeutic paracentesis. Patients with ovarian malignancy may benefit from surgical debulking and chemotherapy.

TB peritonitis is treated with anti-tuberculous medications, while pancreatic ascites and postoperative lymphatic leak from a distal splenorenal shunt or radical lymphadenectomy may resolve spontaneously.

Chlamydia peritonitis is cured with antibiotics using doxycycline and ascites caused by lupus serositis may respond to glucocorticoids.

Over the years many types of active and passive pumps have been developed but none works reliably. They are prone to obstruction, mechanical failure, and leaks.

Therapeutic paracentesis is often done for symptom relief or in patients with tense ascites. Supplements of albumin should be administered at the same time to prevent hypotension. Terlipressin is recommended instead of albumin, if available.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt is an effective treatment for patients who do not respond to diuretics.

Differential Diagnosis

- Liver Failure

- Biliary disease

- Alcoholic liver disease

- Cirrhosis

- Dilated Cardiomyopathy

- Liver cancer

- Portal hypertension

- Viral hepatitis

- Nephrotic syndrome

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with ascites depends on the cause and chronicity. Disorders that are acute and respond to treatment have a much favorable prognosis, compared to disorders that do not respond.

Complications

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Complications related to paracentesis

- Infection

- Electrolyte imbalance

- Bowel perforation

- Bleeding

- Leak of fluid through abdominal wall

- Injury to the kidneys

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients with ascites need long-term monitoring to assess the effectiveness of treatment. The body weight and urinary sodium levels should be monitored in all patients treated with furosemide.

The goal of treatment is to ensure there is minimal edema and the patient is able to perform some daily living activities.

A low sodium diet is recommended.

Consultations

- Gastroenterologist

- Hepatologist

- General Surgeon

Deterrence and Patient Education

- Limit alcohol intake

- Hepatitis B vaccination

- Sodium restriction is recommended (2000 mg/d)

Pearls and Other Issues

Transfusion of blood products (fresh frozen plasma or platelets) routinely before paracentesis in patients with cirrhosis and coagulopathy, presumably to prevent hemorrhagic complications, is not supported by data

Contraindications to paracentesis include coagulopathy in the presence of DIC, massive ileus with bowel distension unless the procedure is image-guided to guarantee that the bowel is not entered.

Complications of ascites may include but are not limited to the following: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, cellulitis, tense ascites, pleural effusion, and abdominal wall hernias.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

While it may appear that ascites is a GI related problem, the pathology affects almost all organ systems and has very high morbidity and mortality. Ascites is not a benign disorder and depending on the cause can have a mortality exceeding 20%. [12]To prevent complications and improve the quality of life, a streamlined protocol for management is vital.[3][13] (Level V)

Countless articles on an interprofessional approach have been published so that the morbidity and mortality can be improved. Besides the gastroenterologist the following interprofessional group of health professionals is highly recommended:

- Pharmacist to oversee all medications and be alert for drugs that cause liver injury

- Nurses to monitor body weight, abdominal girth, prevent deep vein thrombosis, encourage ambulation and educate the patient and family about the importance of a low sodium diet

- Internist to monitor coagulation parameters and general health of the patient

- Surgeon in case the patient needs decompression of the portal system or a liver transplant

- Nephrologist to monitor renal function

- Dietitian to promote nutrition

- Neurologist to assess mental status

- Radiologist to perform TIPS in patients resistant to diuretics

- Physical therapist to encourage ambulation

Outcomes and Evidence-based Medicine

Overall the prognosis is much worse for patients who have decompensated cirrhosis compared to those with compensated cirrhosis. Even patients who are ambulatory and have cirrhotic ascites have a 3-year mortality rate of 50%. Patients with refractory ascites have a 1-year survival of less than 50%. There are many evidence-based studies on managing patients with ascites.[14] (Level V). The bottom line is that aggressive care of these patients is critical if one wants to avoid the high mortality. Ascites patients are complex to manage and thus the need for an interprofessional team to ensure that the patient gets the right treatment, including a liver transplant.