Continuing Education Activity

The infectious pulmonary process that occurs after abnormal entry of fluids into the lower respiratory tract is termed aspiration pneumonia. The aspirated fluid can be oropharyngeal secretions or particulate matter or can also be gastric content. The term aspiration pneumonitis refers to inhalational acute lung injury that occurs after aspiration of sterile gastric contents. In an observational study, it is found that the risk of patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia in developing aspiration pneumonia is found to be about 13.8%. The mortality rate from aspiration pneumonia is largely dependent on the volume and content of aspirate and can be up to 70%. This activity describes the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of aspiration pneumonia and highlights the role of team-based interprofessional care for affected patients.

Objectives:

- Identify the pathophysiology of aspiration pneumonia.

- Review the evaluation of patients with aspiration pneumonia.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for aspiration pneumonia.

- Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care and outcomes in patients with aspiration pneumonia.

Introduction

The infectious pulmonary process that occurs after abnormal entry of fluids into the lower respiratory tract is termed aspiration pneumonia. The aspirated fluid can be oropharyngeal secretions, particulate matter, or can also be gastric content. The term aspiration pneumonitis refers to inhalational acute lung injury that occurs after aspiration of sterile gastric contents. In an observational study, it is found that the risk of patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia in developing aspiration pneumonia is found to be about 13.8%. The mortality rate from aspiration pneumonia is largely dependent on the volume and content of aspirate and can reach 70%.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Failure of the natural defense mechanisms like the closure of the glottis and cough reflex increases the risk of aspiration. The common risk factors for aspiration include an altered mental status, neurologic disorders, esophageal motility disorders, protracted vomiting, and gastric outlet obstruction. Although the common organisms involved in the etiology of community-acquired pneumonia are Streptococci, Haemophilus, and Gram-negative bacilli, the etiology of aspiration pneumonia depends on the content of aspirate. A prospective study of 95 patients showed that gram-negative bacilli contributed 49%, followed by anaerobes (16%). The major anaerobes isolated were Fusobacterium, Bacteroides, and Peptostreptococcus. In hospital-acquired aspiration pneumonia, gram-negative organisms, specifically Pseudomonas aeruginosa, have to be considered.[5][6][7]

Conditions that increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia include:

- Stroke

- Drug overdose

- Alcohol use disorder

- Seizures

- General anesthesia

- Head trauma

- Intracranial masses

- Dementia

- Parkinson disease

- Esophageal strictures

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Pseudobulbar palsy

- Tracheostomy

- NG tube

- Bronchoscopy

- Protracted vomiting

Epidemiology

Due to a lack of biomarkers, epidemiological studies to discover the incidence of aspiration pneumonia have been difficult. Several studies revealed that aspiration pneumonia contributes 5% to 15% of all community-acquired pneumonia. A retrospective study performed on 628 patients with aspiration pneumonia showed 30-day mortality of 21%. The study also showed that CURB 65, which is a predictor of mortality in community-acquired pneumonia, is not a reliable indicator for aspiration pneumonia. This pneumonia remains one of the common complications following general anesthesia and occurs in one in every 2000 to 30000 cases. A study conducted on individuals older than 65 who underwent cardiovascular surgery showed the incidence of aspiration pneumonia to be 9.8%, with 12 out of 123 patients developing aspiration pneumonia after extubation. A case-control study showed that the incidence of aspiration pneumonia was 18% in nursing home patients and 15% in community-acquired aspiration pneumonia. Since most cases of aspiration pneumonia are silent or unwitnessed, the true incidence rate is difficult to ascertain.

Pathophysiology

In normal healthy adults, the mucociliary mechanism and alveolar macrophages act as defenses in clearing micro aspirations from the oropharyngeal secretions. The pathological process of aspiration pneumonia occurs when the normal defense mechanisms fail in a predisposed individual. The entry of fluid into the bronchi and alveolar space triggers an anti-inflammatory reaction with the release of proinflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukins. Inoculation of organisms of common flora from the oropharynx and esophagus results in the infectious process. Mendelson first studied the pathophysiology of aspiration pneumonitis by inducing gastric contents in the rabbit’s lung and comparing it to 0.1 N hydrochloric acid. Later studies conducted in rats using diluted hydrochloric acid demonstrated the biphasic response with the initial corrosive phase by acidic pH followed by a neutrophil-mediated inflammatory response. Inoculation of normal oropharyngeal flora in the aspirate results in the infectious process and results in aspiration pneumonia. If the bacterial load of aspirate is low normal host defenses will clear the secretions and prevent infection.

History and Physical

The common clinical features that should raise suspicion for aspiration include sudden onset dyspnea, fever, hypoxemia, radiological findings of bilateral infiltrates, and crackles on lung auscultation in a hospitalized patient. The common site involved depends on the position at the time of aspiration, commonly the lower lobes are involved in an upright position, and superior lobes can be involved in the recumbent position. The radiological findings will develop within 2 hours after aspiration, and bronchoscopy can reveal erythematous bronchi.

Evaluation

There should be a high level of suspicion in diagnosing aspiration pneumonia, especially in critically ill hospitalized patients. Antibiotic treatment should be initiated immediately, and imaging studies should not delay the treatment. The commonly utilized imaging studies are chest x-ray and computed tomography of the chest, which will help in localizing the site of aspiration. However, most cases are unwitnessed aspiration, which makes it very hard to distinguish between aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. Clinical features may help to distinguish between the two. In aspiration pneumonitis, a large volume of gastric content has to be aspirated to produce chemical pneumonitis and can quickly progress to acute lung injury with subsequent development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Whereas, in aspiration pneumonia, aspiration can be of smaller volumes and can be unwitnessed, which with inoculation of bacteria progress to features of pneumonia and subsequent development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

The arterial blood gas can be used to assess pH status and oxygenation. Sputum analysis is not helpful as it usually reveals a multitude of organisms, while blood cultures have a low yield and are not used frequently.

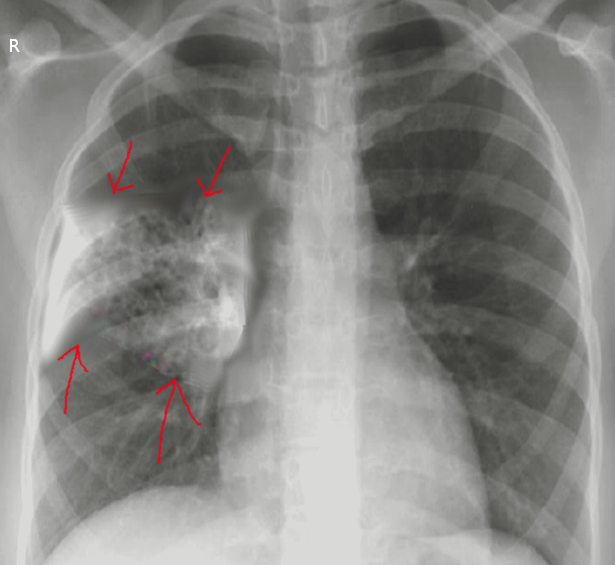

Imaging

On the chest x-ray, the right lower lobe is most frequently involved. Patients who have aspirated while upright may have bilateral lower lobe involvement. Patients lying in the left lateral decubitus position tend to have left-sided infiltrates. The involvement of the right upper lobe is more common in patients who aspirate in the prone position and those with alcohol use disorder.

Bronchoscopy is indicated when particles of food have been aspirated. The technique also allows the retrieval of organisms for culture.

Treatment / Management

The treatment varies between aspiration pneumonia and aspiration pneumonitis. The patient's position should be adjusted, followed by the suction of oropharyngeal contents with the placement of the nasogastric tube. In patients who are not intubated, humidified oxygen is administered, and the head end of the bed should be raised by 45 degrees. Close monitoring of the patient's oxygen saturation is important and immediate intubation with mechanical ventilation should be provided if hypoxia is noted. Flexible bronchoscopy is usually indicated for large volume aspiration to clear the secretion and also for obtaining the sample of bronchoalveolar lavage for quantitative bacteriological studies. In general practice, antibiotics are initiated immediately even though they are not required in aspiration pneumonitis to prevent the progression of the disease. The choice of antibiotics for community-acquired aspiration pneumonia are ampicillin-sulbactam or a combination of metronidazole and amoxicillin. In patients with penicillin allergy, clindamycin is preferred. However, in hospital-acquired aspiration pneumonia, antibiotics are needed that cover resistant gram-negative bacteria and S. aureus, so the use of a combination of vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam is most widely used. Once the culture results are obtained, the antibiotic regimen should be narrowed to be organism-specific.[8][9][10][11]

Oxygenation is often needed, and some patients may even require mechanical ventilation.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia are the following:

- ARDS

- Bronchitis

- Mycoplasma pneumonia

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Viral pneumonia

- Septic shock

Prognosis

The prognosis is dependent on the patient age and other comorbidities. However, despite optimal treatment, death rates of 11 to 30% have been reported. Even those who survive have a prolonged recovery, and repeated admissions are common.

Complications

Complications of aspiration pneumonia include:

- ARDS

- Empyema

- Lung abscess

- Parapneumonic effusion

- Respiratory failure

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Once the aspiration is treated, measures should be taken to prevent further episodes. Patients should be told to sleep with the head of the bed elevated.

Those with swallowing difficulty should eat small meals that are thickened.

Pearls and Other Issues

The disease syndrome that occurs after macro aspiration of gastric and oropharyngeal contents leading to acute pulmonary infection is aspiration pneumonia. It is important to understand and distinguish between aspiration pneumonitis, an inflammatory process that occurs post-aspiration, and aspiration pneumonia for guiding treatment. Since the major complication of this disease syndrome results in ARDS, prompt treatment with supplemental oxygen, antibiotics, and measures to prevent further aspiration has to be undertaken. Close monitoring of the patient for hypoxia is mandated, and if present, the patient should be intubated and mechanically ventilated. In a meta-analysis conducted by Kosaku K. et al., it is found that aspiration pneumonia is associated with high-30-day and in-hospital, but outside the intensive care setting, mortality rates in patients with community-acquired pneumonia.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Aspiration pneumonia carries enormous morbidity and mortality. Delays in diagnosis and treatment result in a prolonged hospital stay and additional complications. The management of aspiration pneumonia is with an interprofessional team that consists of a nurse practitioner, primary care provider, internist, infectious disease specialist, radiologist, pulmonologist, and a speech-language pathologist.

ICU nurses need to recognize aspiration and take appropriate measures. The head of the bed should be elevated, and if there is suspicion of aspiration, a swallow study should be performed before initiating feedings. The nurse should work with the clinician on educating the patient and family to minimize risks. A dietary consult should be made to determine the optimal method of providing nutrition. Patients need to be observed for respiratory distress. Further, these patients need pressure sore preventive measures and prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis.

Besides treating pneumonia, it is important to educate the staff looking after the patient on further prevention of aspiration. This means having the head of the bed elevated, close monitoring of oxygen status, and regularly suctioning the oral cavity in patients with swallowing difficulties. Patients with suspected aspiration should be evaluated by a speech pathologist.

A board-certified infectious disease pharmacist and infectious disease consultant should check the cultures and recommend the appropriate antibiotics. The choice of antibiotics for community-acquired aspiration pneumonia is ampicillin-sulbactam, or a combination of metronidazole and amoxicillin can be used. In patients with penicillin allergy, clindamycin is preferred. However, in hospital-acquired aspiration pneumonia, antibiotics that cover resistant gram-negative bacteria and S. aureus, so the use of a combination of vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam is most widely used. Once the culture results are obtained, the antibiotic regimen should be narrowed to organism-specific antibiotics.

Outcomes

The outlook for patients with aspiration pneumonia depends on the severity of the infection, comorbidity, age, presence of ARDS, and response to antibiotics. If there is a delay in treatment, the mortality rates are high.[5] [Level 5]