Continuing Education Activity

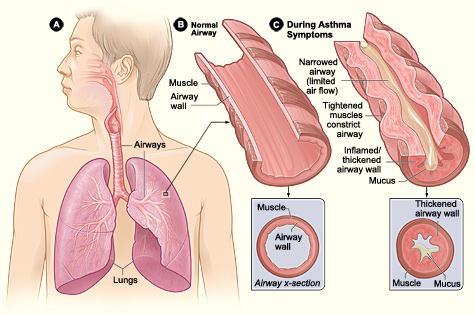

Asthma is a chronic disease of the air passages characterized by inflammation and narrowing of the airways. Symptoms of asthma include shortness of breath, cough, and wheezing. It commonly presents in childhood and is usually associated with conditions such as eczema and hay fever. This activity outlines the evaluation and treatment of asthma and explains the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the epidemiology of asthma.

- Identify the typical patient history of asthma.

- Summarize the use of pulse oximetry and peak flow measures in the bedside evaluation of asthma.

- Outline the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team members to improve outcomes in patients affected by asthma.

Introduction

Asthma is a common disease and has a range of severity, from a very mild, occasional wheeze to acute, life-threatening airway closure. It usually presents in childhood and is associated with other features of atopy, such as eczema and hayfever.[1][2][3]

Asthma is a very common childhood illness leading to multiple hospital admissions and increased healthcare costs. The key feature is airway hyper-responsiveness, which can be triggered by many factors. If not treated promptly, asthma has a high mortality.[4]

Etiology

Asthma comprises a range of diseases and has a variety of heterogeneous phenotypes. The recognized factors that are associated with asthma are a genetic predisposition, specifically a personal or family history of atopy (propensity to allergy, usually seen as eczema, hay fever, and asthma).[5][6]

Asthma also is associated with exposure to tobacco smoke and other inflammatory gases or particulate matter.

The overall etiology is complex and still not fully understood, especially when it comes to being able to say which children with pediatric asthma will carry on to have asthma as adults (up to 40% of children have a wheeze, only 1% of adults have asthma), but it is agreed that it is a multifactorial pathology, influenced by both genetics and environmental exposure.

Triggers for asthma include:

- Viral respiratory tract infections

- Exercise

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Chronic sinusitis

- Environmental allergens

- Use of aspirin, beta-blockers

- Tobacco smoke

- Insects, plants, chemical fumes

- Obesity

- Emotional factors or stress

Epidemiology

Asthma is a common pathology, affecting around 15% to 20% of people in developed countries and around 2% to 4% in less developed countries. It is significantly more common in children. Up to 40% of children will have a wheeze at some point, which, if reversible by beta-2 agonists, is termed asthma, regardless of lung function tests. Asthma is associated with exposure to tobacco smoke and inhaled particulates and is thus more common in groups with these environmental exposures.[7][8]

In childhood, asthma is more common in boys with a male to female ratio of 2:1 until puberty when the ratio becomes 1:1. After puberty, the prevalence of asthma is greater in females, and adult-onset cases after the age of 40 years are mostly females. Asthma prevalence is greater in extreme of ages due to airway responsiveness and lower levels of lung function.[9]

Of all the asthma cases, about 66% are diagnosed before the age of 18 years. almost 50% of children with asthma have a decrease in severity or disappearance of symptoms during early adulthood.[10]

Pathophysiology

Asthma is a condition of acute, fully reversible airway inflammation, often following exposure to an environmental trigger. The pathological process begins with the inhalation of an irritant (e.g., cold air) or an allergen (e.g., pollen), which then, due to bronchial hypersensitivity, leads to airway inflammation and an increase in mucus production. This leads to a significant increase in airway resistance, which is most pronounced on expiration.

Airway obstruction occurs due to the combination of:

- Inflammatory cell infiltration.

- Mucus hypersecretion with mucus plug formation.

- Smooth muscle contraction.

These irreversible changes may become irreversible over time due to

- Basement membrane thickening, collagen deposition, and epithelial desquamation.

- Airway remodeling occurs in chronic disease with smooth muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia.

If not corrected rapidly, asthma may become more difficult to treat, as the mucus production prevents the inhaled medication from reaching the mucosa. The inflammation also becomes more edematous. This process is resolved (in theory complete resolution is required in asthma, but in practice, this is not checked or tested) with beta-2 agonists (e.g., salbutamol, salmeterol, albuterol) and can be aided by muscarinic receptor antagonists (e.g., ipratropium bromide), which act to reduce the inflammation and relax the bronchial musculature, as well as reducing mucus production.[11]

Toxicokinetics

The only relevant toxicokinetics in asthma relates to its management as the absorption and systemic side effects of the beta-2 agonists must be monitored. Typically these will be removed from the body in 2 to 4 hours if salbutamol and albuterol, 18 to 24 hours if salmeterol, or 48 to 72 hours if clenbuterol, which is no longer used in the management of asthma.

The side effects of the beta-2 agonists include tachycardia, flushing, sweating, and other signs of sympathetic system overdrive. There is also the chance of iatrogenic hypokalaemia, which must be monitored.

History and Physical

Patients will usually give a history of a wheeze or a cough, exacerbated by allergies, exercise, and cold. There is often diurnal variation, with symptoms being worse at night. Patients may give a history of other forms of atopy, such as eczema and hay fever. There may be some mild chest pain associated with acute exacerbations. Many asthmatics have nocturnal coughing spells but appear normal in the day time

Physical exam findings will depend on whether the patient is currently experiencing an acute exacerbation.

During an acute exacerbation, there may be a fine tremor in the hands due to salbutamol use, and mild tachycardia. Patients will show some respiratory distress, often sitting forward to splint open their airways. On auscultation, a bilateral, expiratory wheeze will be heard. In life-threatening asthma, the chest may be silent, as air cannot enter or leave the lungs, and there may be signs of systemic hypoxia.

Children with imminent arrest may appear drowsy, unresponsive, cyanotic, and confused. Wheezing may be absent, and bradycardia may occur, indicating severe respiratory muscle fatigue.

Life-threatening asthma is a type of asthma that does not respond to systemic steroids and beta 2 agonist nebulization. It is necessary to identify it early as it may lead to high mortality. It has the following characteristic findings on examination

- Peak expiratory flow less than 33% of personal best

- Oxygen saturation less than 92%

- The normal partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- Silent chest

- Cyanosis

- Feeble respiratory effort

- Bradycardia

- Arrhythmias

- Hypotension

- Confusion, coma

- Exhaustion

In near-fatal asthma, the partial pressure of carbon dioxide is raised, or mechanical ventilation is required with raised inflation pressures.

Evaluation

Bedside

Pulse oximetry can be useful in assessing the severity of an asthma attack or monitoring for deterioration. Note that pulse oximetry lag, and the physiological reserve of many patients means that a falling pO2 on pulse oximetry is a late finding, indicating a severely unwell or peri-arrest patient.

Peak flow measures also can be used to assess asthma and should always be checked against a nomogram as well as the individual patient's normal baseline function. The different severities of acute asthma attacks have an associated peak flow measurement, recorded as a certain percentage of expected peak flow.

Laboratory

Urea and electrolytes (kidney function) should be taken if the patient has a high dose or repeat salbutamol, as one of the side effects of salbutamol is to cause potassium to shift into the intracellular space transiently, which can induce a transient, iatrogenic hypokalaemia. Eosinophilia is common but is not specific for asthma. Recent studies show that levels of sputum eosinophils may guide therapy. In addition, some patients may have an elevation of serum IgE.

Arterial blood gas may reveal hypoxemia and respiratory acidosis. Studies indicate that periostin may be a marker for asthma, but its clinical role remains unsettled.

An ECG will reveal sinus tachycardia, which may be due to asthma, albuterol, or theophylline.

Imaging

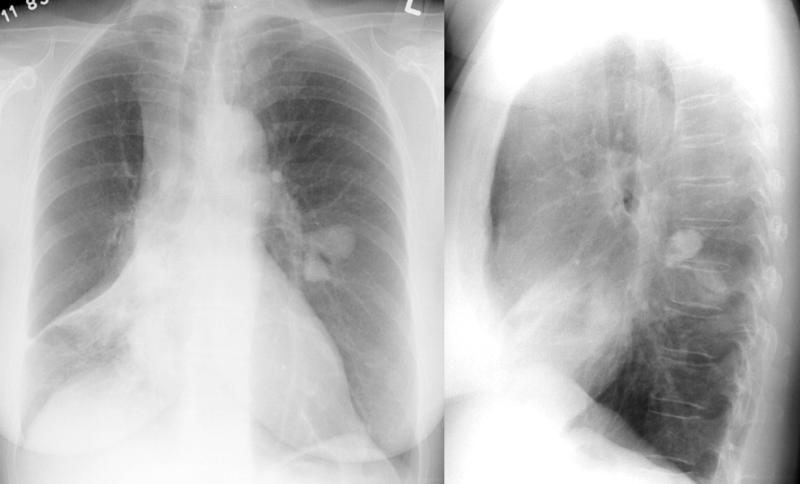

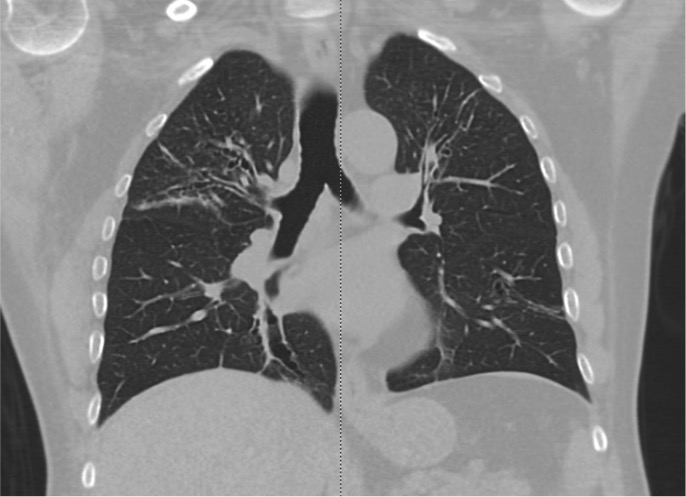

A chest x-ray is an important test, especially if patients have a history of risk of the potential foreign body or possible infection. A Chest CT scan is done in patients with recurrent symptoms who do not respond to therapy.

Special Tests

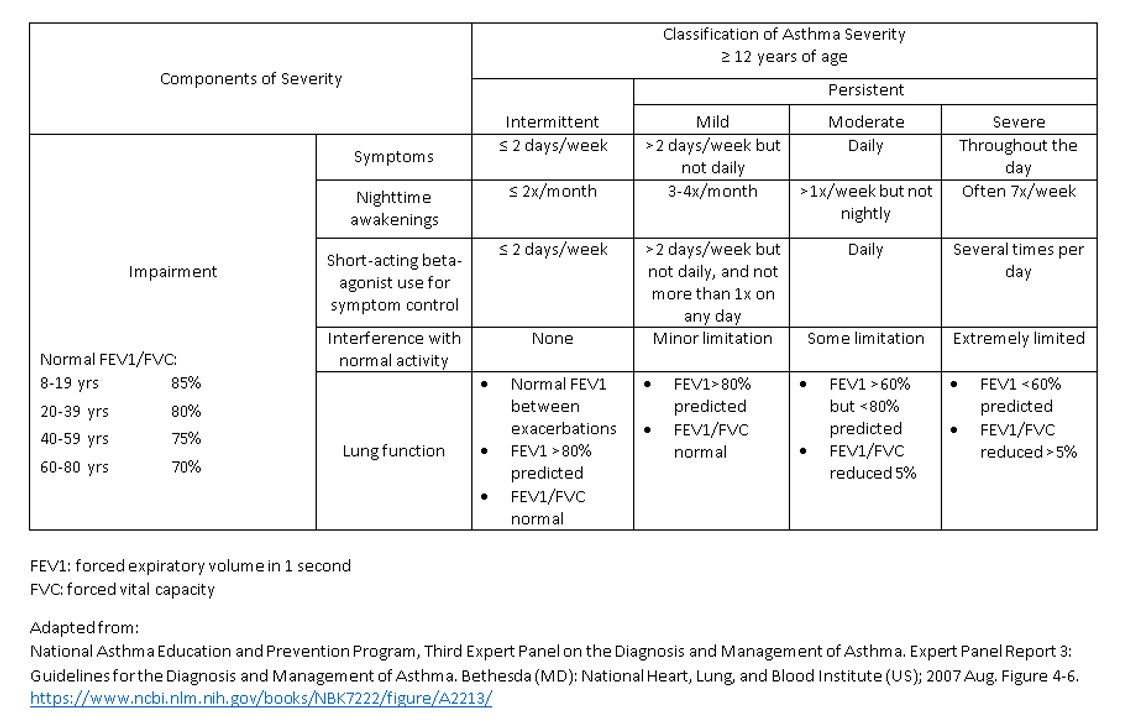

Spirometry is the diagnostic method of choice and will show an obstructive pattern that is partially or completely resolved by salbutamol. Spirometry should be done before treatment to determine the severity of the disorder. A reduced ratio of FEV1 to FVC is indicative of airway obstruction, which is reversible with treatment. Reversibility testing is done by giving the patient inhaled short-acting beta 2 agonists, and after that, the spirometry test is repeated. If there is a 12% or 200ml improvement in FEV1 from the previous value, then it shows reversibility and diagnostic for bronchial asthma. Peak expiratory flow measurement is common today and allows one to document response to therapy. A limitation of this test is that it is effort dependent.

In some patients, a methacholine/histamine challenge may be required to determine if airway hyper-reactivity is present. This test should only be done by trained individuals.

Exercise spirometry may help identify patients with exercise-induced bronchoconstriction.

Treatment / Management

Conservative Measures

Measures to take include calming the patient to get them to relax, moving outside or away from the likely source of allergen, and cooling the person. Removing clothing and washing the face and mouth to remove allergens is sometimes done, but it is not evidence-based.[12][13][14]

Environmental control is vital if one wants to avoid recurrent attacks. Allergen avoidance can significantly improve the quality of life. This means avoiding tobacco, dust mites, animals, and pollen.

Weight reduction in obese asthmatics leads to improved control.

Allergen immunotherapy remains controversial. Large studies have not shown any significant benefit, and the technique is prohibitively expensive.

Monoclonal antibody therapy is indicated for patients with moderate to severe asthma who have a positive skin test. The treatment can lower IgE levels, which in turn decreases histamine production. However, the cost of the injections is high.

Bronchial thermoplasty is a relatively new technique that delivers thermal energy to the airway wall and reduces the narrowing of the airways. Several studies show that it can reduce emergency visits and days missed from school.

Medical

Medical management includes bronchodilators like beta-2 agonists and muscarinic antagonists (salbutamol and ipratropium bromide respectively) and anti-inflammatories such as inhaled steroids (usually beclometasone but steroids via any route will be helpful).

There are five steps in the management of chronic asthma; treatment is started depending on the severity and then escalated or de-escalated depending on the response to treatment.[15]

Step 1: The Preferred controller is as needed low dose inhaled corticosteroid and formoterol.

Step 2: The preferred controllers are daily low dose inhaled corticosteroid plus as-needed short-acting beta 2 agonists.

Step 3: The preferred controllers are low dose inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta 2 agonists plus as-needed short-acting beta 2 agonists.

Step 4: The preferred controller is a medium-dose inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta 2 agonist plus as-needed short-acting beta 2 agonists.

Step 5: High dose inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta 2 agonist plus long-acting muscarinic antagonist/anti-IgE.

Indications for admission

If a patient has received three doses of an inhaled bronchodilator and shows no response, the following factors should be used to determine admission:

- The severity of airflow obstruction

- Duration of asthma

- Response to medications

- Adequacy of home support

- Any mental illness

Patients with life-threatening asthma are managed with high flow oxygen inhalation, systemic steroids, back to back nebulizations with short-acting beta 2 agonists, and short-acting muscarinic antagonists and intravenous magnesium sulfate. Early involvement of the intensive care team consultation helps to reduce mortality. In the case of near-fatal asthma, early intubation and mechanical ventilation are needed.

Surgical

There is no surgical input into the management of typical asthma.

Other/Long Term

Weight loss, smoking cessation, occupational change, and self-monitoring are all important in preventing disease progression and reducing the number of acute attacks.

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential for an acute, life-threatening asthma attack is an anaphylactic reaction. In this case, the patient may also present with orofacial swelling, a rash, and itching. The patient will partially respond to salbutamol and steroids, but intramuscular adrenaline is the lifesaving medication needed to manage these patients.

Other differentials include vocal cord dysfunction, tracheal or bronchial obstruction due to foreign body or tumor, heart failure, gastroesophageal reflux, chronic sinusitis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Staging

Chronic asthma is usually classified as follows:

- Intermittent

- Mild persistent

- Moderate persistent

- Severe persistent

Acute asthma is classified as below:

- Acute severe asthma

- Life-threatening asthma

- Near-fatal asthma

Prognosis

Asthma is not a benign illness and accounts for 1 death per 100,000 people in some countries. The mortality is related to lung function and is exacerbated by smoking. Factors that affect mortality include age more than 40 years, cigarette smoking more than 20 pack-years, blood eosinophilia, FEV1 of 40-70% of predicted, and greater reversibility.[16] Asthma leads to loss of time from work and school; it also leads to multiple hospital admissions increasing the cost of healthcare. Poorly controlled asthma can be disabling and leads to poor quality of life.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients with asthma need life-long follow up for monitoring of the disease, quality of life, and functional status. At each visit, compliance with medications should be emphasized.

Asthma is not a curable disorder, and patients need life long monitoring. Patients should be educated about the need for monitoring of the disease and compliance with medications. The patient should be given a written asthma action plan.

Consultations

- Pulmonology consultation.

- Involvement of the intensive care unit early in cases of severe persistent asthma and life-threatening asthma.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education about the disease and modifying behavior is vital. The patient should also be encouraged to change lifestyle and control the environmental trigger factors.

Patients should be asked to maintain healthy body weight as evidence reveals that the disorder is more difficult to control in overweight individuals.

Patients should avoid tobacco and use of beta-blockers, aspirin, and sulfites.

Pearls and Other Issues

Disposition

If the patient requires nebulized salbutamol and is not ordinarily on home nebulizers, he or she should be admitted. Anyone who has presented with severe or life-threatening asthma should usually be monitored to ensure that the disease does not return when the medication has worn off.

Pitfalls

Issues include forgetting to remove the nebulizer mask once the nebulizer is done (thus leaving the patient on only 6L of 02/min, rather than changing them to 15 L/min via a non-rebreather mask), not assessing inhaler technique, and neglecting to stress the importance of maintenance therapy with inhaled steroids even when the patient is well.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In many countries, including the US, asthma kills one out of every 100,000 persons. The worse the lung function, the higher the mortality. In addition, mortality has also been linked to poor management and lack of medication compliance, especially in young people. Other factors that increase the risk of death include smoking and use of illicit drugs.

Asthma also results in millions of school and workdays lost. In the US alone, close to 2 million asthmatics seek regular care in the emergency department, which also increases the costs of healthcare.

Even though asthma is a reversible disorder, poor lifestyle and lack of management can lead to airway remodeling that leads to chronic symptoms, which are disabling.[17]

The disorder has no cure, and thus life long monitoring is necessary. For best outcomes, an interprofessional approach is recommended.

Evidence-based Medicine

Many guidelines have been published for the diagnosis and management of asthma, but the most critical feature is patient education. The nurses are the last professionals to see the patient before discharge from the emergency department or the floors. Similarly, since most asthmatics are treated as outpatients, pharmacists encounter them regularly. Evidence shows that teaching patients about this disorder and the importance of compliance are critical for good outcomes. The patient should be taught about monitoring techniques, inhaler use, and modifying the environment. A social worker should be involved in the care to ensure that the patient has adequate home support and facilities.

Many evidence-based asthma plans are available for the management of asthma and should be handed out to patients. Finally, nurses also play a vital role in school-based asthma education programs that can help improve self-esteem, knowledge, and self-management behaviors.[18][19][20] (Level II)

Management of asthma requires an interprofessional approach. Nurses work with the clinician in providing patient and family education regarding avoiding triggers, regular use of medications and being prepared with rescue inhalers. The pharmacist should assist with the appropriate use of inhalers and encouraging daily medication administration. The pharmacist should carefully examine the current medications and make sure the patient is not taking any medications that may trigger an attack, working with the prescriber to modify the treatment. an interprofessional approach will result in the best outcomes. [Level V]

Outcomes

Despite great awareness of the disease, asthma still results in high morbidity and even mortality. There are universal guidelines on managing the disorder, but patient compliance with medications remains a big problem. Hence, all healthcare workers have a responsibility to encourage medication compliance and close follow up with the primary care physician.[21][22](Level V)