Continuing Education Activity

Asthma is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Numerous studies have shown that early institution of inhaled corticosteroids can reduce exacerbations and decrease the frequency of associated hospital admissions. This activity outlines the diagnosis, management and treatment of environmental and allergic asthma and describes how to prevent exacerbations of it. It highlights the importance of the interprofessional team in helping educate patients about compliance with treatment and prevention of exacerbations by identifying the triggers.

Objectives:

- Summarize the pathophysiology behind allergic and environmentally induced asthma.

- Explain the common physical exam findings associated with asthma.

- Outline the goals for management of environmental and allergic asthma.

- Outline the importance of collaboration and coordination among the interprofessional team to enhance patient care and help prevent asthma exacerbations.

Introduction

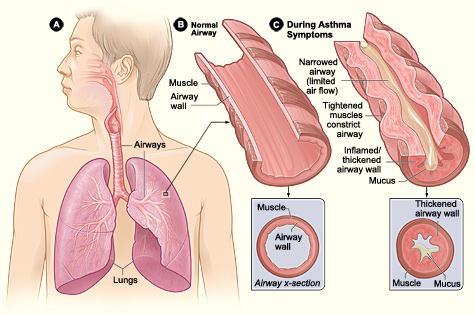

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute defines asthma as a chronic inflammatory disorder. Many cells including mast cells, eosinophils, macrophages, neutrophils, T-lymphocytes, and epithelial cells contribute to the inflammation that occurs. The inflammation can lead to the symptoms of asthma that arise; such as shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing and chest tightness.

Asthma is an obstructive airway disorder, limiting expiratory airflow. It is both acute and reversible and is characterized by obstruction of airflow due to inflammation, bronchospasm and increased airway secretions. Asthma is a disease that impacts all races, ages, sexes, and ethnic groups. It is estimated that 7% of Americans have asthma. Asthma and atopy have dramatically increased in westernized countries. Despite the high prevalence of disease there have been improved outcomes and fewer hospitalizations for asthma attacks. Asthma is characterized by episodic wheezing, hyperresponsiveness of airways to various stimuli and obstruction of airways. These symptoms may occur a few times a day or a few times a week, depending on the person. The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel guidelines for the management of asthma recommend that patients who require daily asthma medications have allergy testing for perennial indoor and outdoor allergens.

Etiology

The etiology of asthma can be multifactorial. It is thought to be a combination of genetic and environmental factors. However, the primary factor underlying all types of asthma is an exaggerated hypersensitivity response. This is described as an IgE-mediated response. This response is triggered by an offending agent, whether it be an allergen or environmental agent (such as air pollutants) resulting in an increased presence of eosinophils, lymphocytes and mast cells. This causes airway inflammation and damage to the bronchial epithelium. Cytokines have also been identified as a contributing factor to the pathogenesis of asthma. Abnormal smooth muscle and contractility and smooth muscle mass are also contributing factors. Allergic asthma attacks are related to exposure to specific offending agents.

The strongest risk factor for developing asthma is a history of atopic disease. Those that have hay fever or eczema have a much higher risk of asthma.

Environmental triggers include exercise, hyperventilation, hormonal changes, and emotional upset, airborne pollutants, as well as GERD.

Environmental pollutants may affect asthma severity it might act as a trigger leading to an asthma exacerbation. The pollutant can exacerbate a pre-existing airway inflammation.

There have been several studies to support the effects of allergies and allergens in triggering asthma.

Both indoor and outdoor allergens and pollutants need to be considered these include:

- Biologic allergens (dust mites, cockroaches, animal dander, and mold)

- Environmental tobacco smoke-smoking during pregnancy and after delivery is related to a substantial risk of developing asthma

- Irritant chemicals and fumes-traffic pollution and high ozone levels

- Products from combustion devices

Occupational asthma is the most prevalent lung disease in industrialized countries and represents 15% of the new asthma cases in adults. It is defined as a variable airflow limitation or hyper-responsiveness due to a particular occupational environment. Occupational asthma may be caused by allergens or irritants in the workplace.

The hygiene hypothesis is an evolving theory that states an abnormally clean environment that limits childhood exposure to triggers and infections, which cause a "naive" immune system, increases the incidence of asthma and allergies. [1]

Epidemiology

According to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1 in 13 people has asthma. It affects 25.7 million Americans, including 7.0 million children younger than 18 years. It is a significant health and economic burden on patients, families, and society. Important epidemiologic issues include:

- In 2010, 1.8 million people visited an emergency room for asthma-related care, and 439,000 people were hospitalized because of asthma.

- The most recent data obtained from the CDC shows prevalence in males at about 6.5% and in females about 9.1%.

- Regarding race distribution, the prevalence is 7.8% in the white population, 10.3% in the black community and 6.6% in the Hispanic population.

- The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 235 million people currently have asthma.

- The annual incidence of occupational asthma ranges from 12 to 170 cases per million worked. The prevalence is reported at 5% to 15% across many different industries.

- Asthma is the most common noncommunicable disease among children.

- Most deaths occur in older adults.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of asthma is well recognized and is characterized by variable airflow constriction and airway hyperresponsiveness, thereby causing a contractile response of the airways due to a variety of stimuli. The airway inflammation associated with asthma is felt to be the role of mast cell activation mediated by a variety of cells and cytokines similar to the pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis.

Eosinophils are the most specific cells that accumulate in asthma and allergic inflammation and also correlate with disease severity. Variable narrowing of the airway lumen causes variable reductions of airflow which is pathognomonic of asthma.

Bronchoconstriction may be due to the direct effects of contractile agonists released from inflammatory cells or reflex neural mechanisms. There is also a subset of patients with asthma who have irreversible airflow obstruction which is believed to be caused by airway remodeling. Structural cells, epithelium, fibroblasts, smooth muscle, and endothelium may contribute to airway remodeling through the combination of mediators and cytokines.

There are a variety of genetic, environmental and infectious factors that appear to modulate whether susceptible individuals progress to overt asthma. [2]

Histopathology

The histopathology of asthma is characterized by some structural changes, including epithelial detachment, subepithelial fibrosis, inflammatory cell infiltrate, bronchial smooth muscle hypertrophy, mucous gland hypertrophy, and vascular changes. These changes can be seen in the proximal airways as well as the distal lung and can be seen in endobronchial biopsies of mild, moderate, and severe asthma. [1]

History and Physical

Pertinent History

- Onset of symptoms

- Environmental triggers (inside and outside the home) and risk factors (such as tobacco use or exposures)

- Current therapy and previous history specific to their attacks

- History of prior hospitalization or intubation for asthma

- Occupation (sensitizers and 10% by irritants cause 90% of occupational asthma)*

- Ask about food allergies

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms

- Use of medications such as NSAIDs and aspirin

- If exercise triggers shortness of breath

Asthma Symptoms

- Coughing

- Shortness of breath

- Wheezing

- Chest tightness or pressure

Physical Examination Findings during an Acute Exacerbation

- Tachypnea

- Wheezing

- Accessory muscle use

- Retractions

- Prolonged expiratory phase

- Sometimes there is limited air movement which can occur in severe cases

* Sensitizers include animals, bioaerosols, drugs, enzymes, latex, plants, seafood, acid anhydrides, metals, wood dust, persulfate, rosin, and isocyanates. Irritants include chlorine and high-level dust and smoke. [3],[4]

Evaluation

Initial Evaluation

- Pulse oximetry

- Peak flow

- Spirometry-generally if the measured FEV1(forced expiratory volume in one second) improves more than 12% and increases by 200 milliliters following bronchodilator it is supportive of the diagnosis

- Chest x-ray if indicated

- Flu swab/RSV can be performed if concerned about a virus triggering asthma

- ABG may be warranted depending on the severity of symptoms

For any patient with a new onset of asthma, occupational asthma should be considered the following tests can be ordered to verify this:

- Measure peak flow

- Obtain spirometry and also peak expiratory flow rate that can be monitored inside work and outside of work

- Skin prick tests can also be performed to test for allergies

- Methacholine challenge can be performed

- Specific inhalation challenges can also be completed

Biomarkers of inflammation are being evaluated for their usefulness in the diagnosis of asthma. Biomarkers include total and differential cell count and mediator assays in sputum, blood, urine, and exhaled air.

The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel guidelines for asthma recommend that patients who require daily asthma medications have allergy testing for perennial indoor allergens. When the triggers are found, exposure to allergens should be controlled by various measures as discussed below. For patients whose symptoms are not controlled should be referred to an allergist for immunotherapy

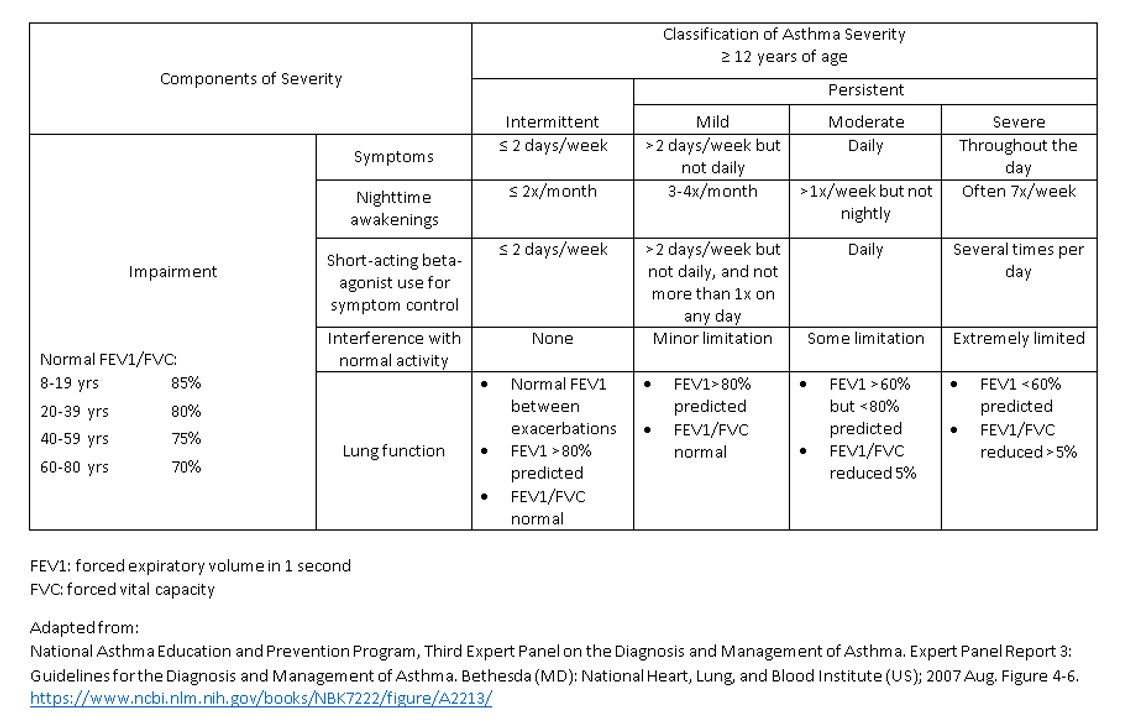

Asthma severity is classified as intermittent, persistent-mild, persistent-moderate, and persistent. Several validated questionnaires have also been used to assess asthma control in patients; these include the Asthma Assessment questionnaire, the Asthma Control Questionnaire, and the Asthma Control Test. During the initial visit, asthma, severity, and control should be assessed to initiate treatment. Then asthma control should be evaluated to determine a treatment plan. [4]

Treatment / Management

The goal of asthma care is to reduce impairment, which is the frequency and intensity of symptoms and functional limitations, as well as reducing the risk of future asthma attacks, a decline in lung function, or medication side effects. Achieving and maintaining asthma controls involves a multidisciplinary approach that includes appropriate medication, addressing environmental factors that may cause a worsening of symptoms and help patients learn self-management and monitoring skills and to adjust therapy accordingly. The goal of treatment is to stop symptoms by reducing airway inflammation and hyperreactivity.

Currently, asthma medications are classified according to their roles in the overall management of asthma quick versus long-term control. All patients should have available a fast-acting bronchodilator for use as needed. If these are being used for more than 2 days per week or more than 2 times a month for nighttime awakenings, then a controller medication should be prescribed. The quick-acting inhalers are the most effective to reverse airway obstruction and provide immediate symptomatic relief. The most widely used drugs are beta-agonists such as albuterol. Achieving long-term control of asthma requires a multifactorial approach including the avoidance of environmental stimuli that can provoke bronchoconstriction and airway inflammation as well as monitoring changes in disease activity and sometimes allergen immunotherapy and drug therapy. Inhaled corticosteroids best help patients achieve well-controlled asthma. They work by suppressing airway inflammation and decreasing bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Asthmatics who smoke have less benefit from inhaled corticosteroids than nonsmokers.

Step-Up Therapy: The Goal of Asthma Control

- Step 1: For intermittent asthma, preferred therapy is a short-acting inhaled beta2 agonist. For persistent asthma, daily medication is recommended.

- Step 2: Preferred treatment is a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid.

- Step 3: A low dose inhaled corticosteroid plus a long-acting inhaled beta2 agonist is recommended, or a medium-dose inhaled corticosteroid.

- Step 4: The preferred treatment is a medium-dose inhaled corticosteroid plus a long-acting beta2 agonist.

- Step 5: The preferred treatment is high dose inhaled corticosteroid plus a long-acting beta2 agonist and considering omalizumab for people with allergies.

- Step 6: The preferred treatment is high-dose inhaled corticosteroid plus a long-acting beta2 agonist plus an oral corticosteroid; consider omalizumab with people with allergies.

For steps 2 to 4, also consider allergy immunotherapy and allergy testing. Leukotriene receptor antagonists, cromolyn sodium, and theophylline can be used as alternative treatments but not preferred agents. Leukotriene inhibitors have shown to improve exercise-induced asthma by 50% for children 12 and older. The decision to step up therapy is based on control of symptoms, of how often short-acting inhaler is being used, nighttime awakenings, interference with activity and questionnaires. Compliance, inhaler technique, environmental control, and comorbidities should also be assessed. Consideration to step down therapy if asthma is controlled for at least 3 months.

Patients using inhalers should be encouraged to use spacers, especially in children. Studies have shown if the inhaler is used appropriately with a spacer it is just as useful as a nebulizer machine.

Allergen and environmental control are very important in asthmatics as well. The primary factor in the environmental control program is the avoidance of dust mites. Sensitivity to dust mites is a strong predictor of asthma and asthma severity. When controlling exposure to dust mites, it is recommended to encase mattresses and pillows in vinyl covers and wash all bedding every 1 to 2 weeks in hot water. Other measures include reducing humidity, removing carpets from bedrooms, and limiting lying on upholstered furniture. In rooms of children stuffed animals should be washed or removed from beds. If unable to remove rugs, using a HEPA filter will reduce allergen emissions. Wearing a mask while using a regular vacuum helps as well.

Pets especially cats can also be a potential trigger for asthma and allergies and typically should be removed from the house. High exposure to cockroach allergen has been associated with the risk of asthma and the highest concentration in the kitchen. Allergy to fungus is a risk factor for asthma. When there are high spore counts in your location s person with asthma and allergies should avoid prolonged outdoor activity. Tobacco exposure should be avoided as it has been shown to increase medication requirements and also decrease lung function. Maternal smoking during pregnancy has been associated with increases in child risk of developing asthma. Air pollution can also contribute to exacerbating asthma as well.

Management of Acute Exacerbations

- Correcting severe hypoxemia through the application of oxygen and repetitive treatment with short-acting beta2 agonists

- Rapid reversal of airflow obstruction

- Reduction of the risk of relapse

- Anyone with peak expiratory flow below 50% needs immediate medical care.

Medications

- Combination of inhaled anticholinergic and beta2 agonist which have been shown to decrease hospitalization of school-aged children

- Intravenous magnesium sulfate has also been shown to increase lung function and decrease hospitalization in children

- Administering systemic corticosteroids within one hour of an emergency room or urgent care presentation has a significant effect on patients with severe exacerbation and also decreases hospitalization

- Patients should be sent home on oral prednisone after an acute hospitalization [4]

Differential Diagnosis

Making sure a patient has asthma and not another condition is an essential step before initiating treatment.

Adults

- Chronic pulmonary obstructive disease (COPD)

- Congestive heart failure

- gastroesophageal reflux disease

- mechanical obstruction of airways

- vocal cord dysfunction

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Depression and stress

Infrequent Causes

- Pulmonary embolism

- pulmonary infiltrates

- Medications such as ACE inhibitors

Children

In children distinguishing between asthma wheezing versus others, causes can be difficult. The differential in children for wheezing can be the following:

Upper Airway Diseases

- Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis

Obstructions Involving Large Airways

- Foreign body in trachea or bronchus

- Vocal cord dysfunction

- Vascular rings or laryngeal webs

- Laryngotracheomalcia, tracheal stenosis, or bronchostenosis

- Enlarged lymph node or tumor

Obstructions Involving Small Airways

- Viral bronchiolitis

- Cystic Fibrosis

- Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- Primary ciliary dyskinesia syndrome

Other Causes

- Congenital heart disease

- A recurrent cough not due to asthma

- Aspiration

- Gastroesophageal reflux

Staging

See Table 1

Prognosis

The prognosis of asthma is variable amongst adults and children. Children do experience complete resolution more than adults. However, the progression of severe disease is unlikely in both groups unless there are other underlying lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or tobacco abuse. Many studies have shown those patients that have had previous hospitalizations, as well as intubations who are classified as severe asthmatics, have a poorer prognosis. Patients who smoke and have underlying COPD have a poorer prognosis as well in this subset of patients permanent lung impairment can occur.

Many recent studies have shown if inhaled steroids are started early in the course of the disease as well as continuously has a beneficial effect and can improve lung function. [ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10546480]

Complications

Complications from asthma do exist although long-term complications are not common.

Common Complications

- Interference with normal activities

- Interference with sleep

- Time missed from school and work

- Emergency department visits and hospitalizations

Long-term complications from asthma can occur due to chronic inflammation which can lead to damage to the airways. Typically frequent asthma attacks can lead to airway inflammation and eventually medications are unable to penetrate the airway. Death from asthma is rare the risk increases in those patients with underlying lung disease and smokers. [5]

Consultations

Refer patients to an asthma specialist for consultation or co-management following reasons:

- When there are difficulties in achieving or maintaining control of asthma

- If the patient required more than 2 bursts of oral systemic corticosteroids in 1 year or has an exacerbation requiring hospitalization

- If step-4 care or higher is required (step-3 care or higher for children 0 to 4 years of age)

- If immunotherapy or omalizumab is considered

- When additional testing is necessary [6]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated about asthma concerning the use of medications. They should understand how to take medications and also the differences between quick-acting medications and maintenance medications such as inhaled corticosteroids.

Patients should also be encouraged to use an asthma action plan, so they understand when their symptoms are severe, and they need to contact a physician or go to the emergency room.

The asthma APGAR (activities, persistent, triggers, asthma medications, response to therapy) tools in primary care practices have been shown to improve rates of asthma control and reduce emergency room and urgent care visits. [7]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Asthma is considered the most common chronic disease seen in children. It is a significant cause for missing school as well as frequent emergency department and urgent care visits. The use of inhaled corticosteroids has been shown to improve asthma control but adherence is low amongst all populations. In a study performed in Massachusettes between 2012 and 2015, the impact of the school nurse-supervised asthma therapy program on healthcare utilization was reviewed. The children who participated in this study were identified as high risk and had persistent asthma. The study recognized poor adherence to medications by this group of children as well. These children were given their inhaled corticosteroid monitored by the school nurse daily to twice daily. This was a retrospective study where data was analyzed and electronic health records were reviewed to follow asthma-related emergency department and hospital visits both before the study and after the study. Refills of albuterol and prednisone through pharmacy records and medical records were obtained. Lastly, the research assistants reviewed school absenteeism reports from school nurses. [Level III Cohort Case-Control studies] The study showed a reduction in both emergency department and hospital visits as well as decreased refills in albuterol in the post-intervention group versus pre-intervention. This small study showed that collaboration with a school nurse to provide supervised asthma medication can reduce health care utilization in school-aged children and provide better asthma control overall. [8]

In 2013, 1.6 million emergency department visits were due to uncontrolled asthma. Many studies have shown that asthma education is essential to help promote patient self-management and adherence. A retrospective study was done in the South Bronx asthma clinic to show that combining pharmacy expertise with asthma education also improves medication adherence and asthma control, as well as decreasing hospital utilization. The role of the asthma educator is to teach patients about asthma medications, their proper use, and to provide better understanding of the disease. Chart reviews were performed to identify improvement of asthma control after education based on the asthma control test scores. Conclusions from this study show that the addition of a pharmacist lead asthma education program was associated with improved medication adherence, decreased hospital utilization, and increased asthma control. [9] [Level III Cohort Case-Control studies]

Of utmost importance in the treatment and prevention of asthma-associated morbidity and mortality is communication between an interprofessional team of clinicians, pharmacists, and specialized nurses. Communication of medication noncompliance between the pharmacists and clinician can help identifies those patients who are at highest risk of asthma exacerbations. Specialty nurses can help educate the patient on the proper administration of the inhalers and their use. Nurses can help clinicians identify the most appropriate prescription for each patient to ensure proper compliance. Only by working together as an integrated interprofessional unit in the treatment of asthma can we achieve improved patient outcomes. [Level V]