Continuing Education Activity

Astrocytoma arises from astrocytes, the star-shaped glial cells found in the cerebrum. Constituting 60% of brain tumors, glial tumors include astrocytoma as the most prevalent form of glioma. While primarily impacting the brain, they can also affect the spinal cord. These tumors pose a significant threat to individuals across various age groups, contributing to both mortality and morbidity. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are crucial in mitigating the serious consequences associated with astrocytomas.

This educational course provides a comprehensive understanding of astrocytomas, exploring their origin, pathology, classification, and clinical management. It reviews the latest advancements in diagnosis, treatment modalities, and emerging therapies for this prevalent form of glioma. Participants will gain insight into astrocytoma management, enhancing clinical knowledge and improving patient care outcomes. The activity also highlights the role of the interprofessional team in optimizing care coordination for affected patients.

Objectives:

Identify the clinical signs and symptoms of progressive collapsing foot deformity, including medial arch collapse, hindfoot valgus, and forefoot abduction.

Differentiate progressive collapsing foot deformity from other foot pathologies such as plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendonitis, and Charcot arthropathy based on physical examination findings and diagnostic imaging.

Implement appropriate non-surgical interventions for early-stage progressive collapsing foot deformity, including orthotic devices, physical therapy, and activity modification.

Assess interprofessional team strategies for improving comprehensive care and communication for astrocytoma patients.

Introduction

Astrocytomas represent a significant and complex subset of brain tumors originating from astrocytes, the star-shaped glial cells that play a critical role in supporting neuronal function within the cerebrum. Amongst brain tumors, glial tumors comprise 60% of the tumors. As the most common form of glioma, astrocytomas primarily affect the brain, although they can also involve the spinal cord. These tumors present a considerable clinical challenge due to their prevalence and the serious morbidity and mortality they cause across all age groups. The etiology of astrocytomas remains largely elusive, with ionizing radiation being the only well-established risk factor. Associations with other potential risk factors, such as electromagnetic fields, head injury, or occupational exposures, are not yet supported by conclusive evidence.

Etiology

No underlying cause has been identified for the majority of primary brain tumors, and the only established risk factor is exposure to ionizing radiation.[1] Children who receive prophylactic radiation for acute lymphocytic leukemia may have a 22 times higher risk of developing a central nervous system (CNS) malignancy within about 5 to 10 years. It has been shown that pituitary adenoma radiation therapy carries 16 times more risk of glioma development.[2] An association with other factors like exposure to electromagnetic fields (cellular telephones), head injury, or occupational risk factors is unproven.[3]

A minority of patients have a family history of brain tumors. There is a genetic susceptibility to glioma development, for example, in diseases like Turcot syndrome, p53 mutations (Li-Fraumeni syndrome), and neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). Amongst low-grade astrocytomas, about 66% demonstrate p53 mutations.[4]

Epidemiology

Understanding epidemiological patterns for astrocytoma is important for identifying risk factors and improving early detection across various populations and age groups.

Race

Minimal racial differences have been found.[5]

Gender

- There appears to be no gender dominance in pilocytic astrocytomas.

- Study results have demonstrated a man-to-woman ratio of 1.18:1 in low-grade astrocytomas.

- In anaplastic astrocytoma, there is substantial dominance in men, with a man-to-woman incidence reported as 1.87:1.

Age

- The likelihood of pilocytic astrocytoma increases during the first 2 decades of life. Low-grade astrocytomas are predominant in individuals aged 30 to 40, comprising about one-fourth of adult cases.

- The age distribution of patients with low-grade astrocytomas is as follows:

- 10%: younger than 20

- 60%: 20 to 45 years

- 30%: older than 45 years

- For grade 3 astrocytoma, the mean age at diagnosis is approximately 40 years.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of astrocytoma involves the abnormal proliferation of astrocytes, glial cells that provide structural and metabolic support to neurons in the CNS. Multiple mechanisms result in the local effects of astrocytoma. These include direct invasion and competition for oxygen, leading to hypoxic injury to normal brain parenchyma. The tumor microenvironment, which includes interactions with other cell types, extracellular matrix components, and blood vessels, also influences tumor progression. Free radicals, neurotransmitters, and inflammatory mediators also disturb homeostasis. This complex interplay contributes to the heterogeneity and resistance to therapy often observed in astrocytoma cases. Understanding the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying astrocytoma development is essential for advancing diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Genetic mutations and alterations in signaling pathways, such as the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK pathways, are often implicated in the uncontrolled growth and survival of these cells. These mutations can lead to the disruption of normal cellular processes, including cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and differentiation. As a result, astrocytomas can vary in their aggressiveness, from relatively slow-growing pilocytic astrocytomas to highly malignant glioblastomas. The mass effect of the tumor produces various clinical signs and symptoms.

Histopathology

Historically, gliomas were classified by morphological features based on their resemblance to normal tissue. Tumors resembling astrocytes are termed astrocytomas, and tumors similar to oligodendrocytes are referred to as oligodendrogliomas. Recent advances in molecular profiling have revolutionized the diagnostic and classification approach, leading to an integrated morphological and molecular classification that offers greater clinical relevance. These advances were introduced in the revised fourth edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Central Nervous System Tumors in 2016 and further refined in the fifth edition (WHO 2021), which fully integrates molecular diagnostics with histological features. Immunohistochemistry identifies IDH, ATRX, p53, and other important mutations. This new classification is also the first to classify pediatric gliomas separately.

WHO classification (2016) classified diffuse astrocytomas as grades 2, 3, and 4. Grade 1 infiltrating astrocytoma was not mentioned. The classification was based on 4 characteristics as follows:

- Nuclear atypia: nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia

- Mitoses:

- Has to be unequivocal

- Ki67 proliferation index is used to separate grade 2 tumors from grade 3.

- Microvascular proliferation

- Glomeruloid type is the most common, prognostically of lesser significance as it is found in lower-grade gliomas (such as pilocytic astrocytoma)

- Endothelial proliferation is present in the large vessel lumen. It is less common and has more of an association with high-grade gliomas.

- Necrosis:

- Coagulative necrosis

- Pseudopalisading necrosis

WHO Histological Grading: Diffuse Astrocytomas

- Grade 2 (diffuse astrocytoma): nuclear atypia alone

- Grade 3 (anaplastic astrocytoma): nuclear atypia and focal/dispersed anaplasia. Prominent proliferation activity and mitoses are present.

- Grade 4 (glioblastoma): nuclear atypia, mitoses, microvascular proliferation, or necrosis

WHO Histological Grading: Localized Astrocytomas

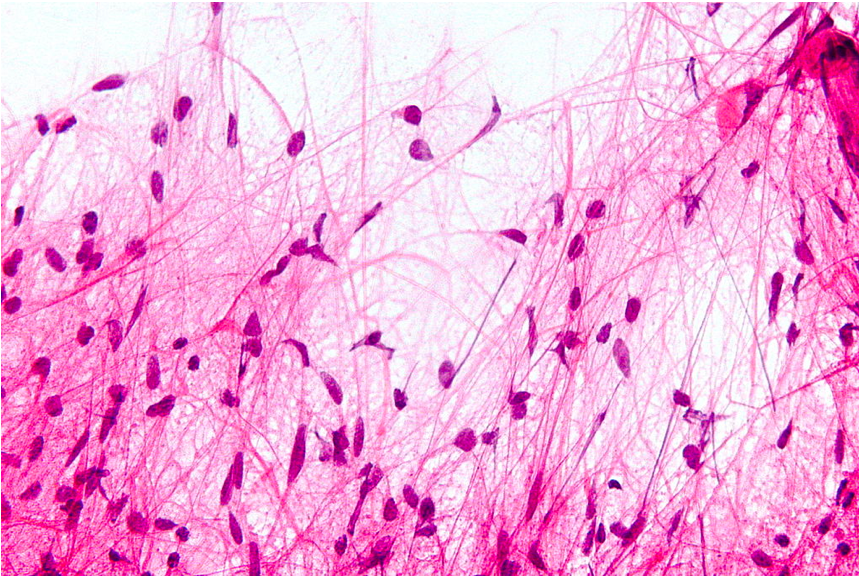

- Pilocytic astrocytoma: corresponds to WHO grade 1 (see Image. Microscopic Features of Pilocytic Astrocytoma)

- Does not recommend definitive grade allotment yet for pilomyxoid astrocytoma

- Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma: grade 1

- Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: grade 2

- Anaplastic pleomorphic astrocytoma: grade 3 [6][7]

The Consortium to Inform Molecular and Practical Approaches to CNS Tumor Taxonomy-Not Official WHO (cIMPACT-NOW) facilitated the WHO classification modifications. The recent 2021 WHO classification utilizes advanced molecular diagnostics to classify CNS tumors. Clinical and molecular differences among diffuse gliomas occurring in adults (adult type) and children (pediatric type) are recognized.[8]

Adult-type glioma classification is now divided into only 3 distinct groups:

- Astrocytoma IDH-mutant: Grades 2, 3, and 4

- Oligodendroglioma IDH-mutant and 1p/19q-codeleted: Grades 2 and 3

- Glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype: Grade 4, including molecular diagnosis of TERT promoter mutation, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene amplification, and gain of chromosome 7 and loss of chromosome 10. As per the revision classification, IDH-wildtype astrocytoma grades 2 and 3 are no longer recognized.

Astrocytoma Tumor Grades

- Grade 1

- Low-grade tumors

- Includes pilocytic astrocytoma and subependymal giant cell astrocytoma

- usually occur in children and young adults

- not considered malignant as it does not spread in the brain

- Grade 2 (previously diffuse)

- Usually seen in adults

- May progress to glioblastoma

- Without microvascular proliferation or necrosis

- Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A/B (CDKN2A/B) non-deleted

- Grade 3 (previously anaplastic)

- Also usually seen in adults

- Characterized by a lack of endothelial proliferation and necrosis

- CDKN2A/B non-deleted

- Grade 4 (previously glioblastoma)

- The most common malignant brain tumor

- Peak age is approximately 65 years

- Bad prognostication

- Variants: giant cell glioblastoma and gliosarcoma

- With microvascular proliferation or necrosis

- CDKN2A/B deleted

Specific Tumor Types

- Diffuse astrocytoma, MYB or MYBL1-altered

- Now, WHO grade 1

- IDH-wildtype pediatric-type diffuse low-grade glioma

- Benign clinical course

- Low recurrence after resection alone

- Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma

- Prognosis is typically good

- Children and young adults affected

- Big lipidized cells

- May mimic malignant tumor

- Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma

- Located mostly intraventricularly

- Benign in nature

- Affects the adolescent age group

- Associated with tuberous sclerosis

- H3 K27M mutant diffuse midline glioma

- High-grade

- Midline location, including the spinal cord, brainstem, or thalamus

- Adolescents and children mainly affected

- Diffuse pontine intrinsic glioma included

- New entry after the 2016 WHO classification

- Poor prognosis usually presents as follows:

- With the absence of EGFR amplification

- With the presence of unmethylated O6-methylgaunine-DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter

- Enhancement on MRI: may or may not be present

- Histologically may range from minimum hypercellularity to full-blown glioblastoma

- Gliomatosis cerebri

- The old term used for extensive and diffuse astrocytomas

- Not a distinct entity since 2016

- Radiological evidence of >3 lobe involvement required bilaterally

- Now, WHO grade 3

- The division into 2 types is possible based on solid component presence as follows:

- Type 1: No IDH 1/2 mutation, diffusely growing

- Type 2: IDH 1 mutation positive, a solid component present

- Genetically overlaps with diffuse astrocytic gliomas, glioblastoma, and oligodendrogliomas

- Gliosarcoma

- WHO considers this a variant of glioblastoma

- Quite rare, with only about 200 case reports

- Demonstrates glioblastoma and sarcoma components (fibroblastic, osseous, cartilage, smooth and striated muscle, fat cells)

- Similar to glioblastomas, usually found in the temporal lobe

- Prognositicallly like glioblastoma

- Immunohistochemistry includes the following:

- The astrocytic component is glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) positive and spindle cell negative

- Smooth muscle part (gliomyosarcoma) is smooth muscle antibody (SMA) and factor VIII positive

- Gliofibroma

- Very rare

- Usually found in children

- Has a fibroblastic component, which is nonmalignant

History and Physical

History

A thorough history of patients with astrocytoma is a critical component of the diagnostic process, providing valuable insights into symptoms' onset, progression, and nature. Symptoms can be divided into 2 categories: general and focal. General symptoms include headache (usually early morning), nausea, vomiting, cognitive difficulties, personality changes, and gait disorders. Localizing symptoms include seizures, aphasia, or visual field defects. About 50% of patients with supratentorial brain tumors may present with seizures. A visual field defect is often unnoticed by the patient and may be revealed after it leads to injury, such as motor vehicle accidents.

It is essential to document the duration, frequency, and severity of these symptoms and any factors that exacerbate or alleviate them. Additionally, the patient's medical history, including prior head injuries, exposure to ionizing radiation, and family history of neurological disorders or cancers, should be thoroughly explored. Clinicians should also assess the patient's functional status, noting any impact on daily activities and quality of life. This comprehensive history helps to establish a timeline of symptom development, identify potential risk factors, and guide further diagnostic evaluations, ultimately contributing to a more accurate and timely diagnosis of astrocytoma.

Physical Examination

The physical examination of patients with astrocytoma involves a comprehensive neurological assessment to evaluate the extent and impact of the tumor on the CNS. During the neurological examination, attention is given to cranial nerve function, motor strength, coordination, sensory perception, and reflexes. Specific tests may include evaluating visual fields, assessing gait and balance, and testing for signs of increased intracranial pressure, such as papilledema. These findings help localize the tumor and gauge its severity, guiding further diagnostic imaging and treatment planning. The examination results, imaging studies, and histological analysis are crucial for establishing an accurate diagnosis and developing an effective treatment strategy.

Evaluation

The evaluation of astrocytomas involves a thorough clinical assessment, advanced imaging techniques, and histopathological analysis. A definitive diagnosis is obtained through a biopsy, where histopathological examination and molecular profiling are performed. These evaluations are critical for accurately grading the tumor, guiding treatment decisions, and predicting prognosis.

Imaging Studies

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the best imaging modality for diagnosing astrocytoma. Gadolinium contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) imaging should be used whenever possible. If there is any contraindication for MRI, such as joint implants or pacemakers in situ, computed tomography (CT) may be performed. Lower-grade gliomas are contrast-enhancing, so fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences of MRI are done.

If a tumor is found, a neurosurgeon must perform a biopsy on it. This involves the removal of a small amount of tumor tissue, which is then sent to a neuropathologist for examination and grading. CT appearance of low-grade astrocytomas is also generally not very definitive. The tuors are homogeneous, not well defined, and appear as poorly defined and non-contrast enhancing lesions. In anaplastic astrocytomas, there may be some contrast enhancement. There may be a possible metastatic disease; hence, whole-body imaging should also be considered to look for an alternate primary.

On MRI, T2 hyperintensity is seen in astrocytomas, whereas on T1, there is isointensity. Tumor vascularity is significant; new techniques are being developed to identify it. These include arterial spin labeling and dynamic contrast enhancement MRI. Functional MRI is an upcoming imaging modality; this is useful pre-surgery to demarcate various areas of the brain based on functionality. Other modalities include positron emission tomography (PET) scan, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and perfusion imaging. These modalities may provide information about the metabolic action in the tumor, the blood flow characteristics, and the constitution of the tumor. With this approach, it can be determined whether the lesion is progressive or necrosed after chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Treatment / Management

Glioma Treatment Recommendations Based on Tumor Grade

Grade 2

- Surgery is recommended with maximal safe resection.

- Unfavorable prognostic factors: age older than 40, dimension ≥4 cm, tumor crossing midline, and presence of neurologic deficit before resection; ≥3 high-risk factors.

- Low-risk, patients younger than 40 can be observed.

- High-risk patients: fractionated external-beam radiotherapy (EBRT) plus adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended.[9]

- The standard radiation dose for low-grade astrocytomas is 45 Gy to 54 Gy, delivered in 1.8 Gy to 2.0 Gy fractions.

- Clinical target volume (CTV) is a 1 cm expansion around the gross tumor volume (GTV).

- Adjuvant therapy includes temozolomide 150 to 200 mg/m2/day orally on days 1 to 5 of a 28-day cycle (12 cycles) or PCV (procarbazine, lomustine, vincristine) for 6 cycles.

- Recurrences or progressive, low-grade disease (previously untreated): Temozolomide 75 mg/m2 by mouth daily on days 1 to 21 or 150 to 200 mg/m2 by mouth on days 1 to 5 of a 28-d cycle until disease progression or for a maximum of 24 cycles.

- Postoperative radiation therapy is often employed for unresectable, residual, or recurrent tumors.

- Chemotherapy is often used for low-grade oligodendrogliomas, particularly tumors with the 1p19q deletion, which is a marker for tumor susceptibility to chemotherapy.

Grade 3

- Standard of care: surgical resection followed by EBRT (54 Gy to 59.4 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions) is recommended.

- Postradiation therapy: continue temozolomide at a dose of 150 to 200 mg/m2/day by mouth on days 1 to 5 every 28 days for 12 cycles OR

- Procarbazine, lomustine, vincristine (PCV)): lomustine (CCNU) 90 to 130 mg/m2 by mouth on day 1 (max-200 mg) plus procarbazine 60 to 75 mg/m2 PO on days 8 to 21 plus vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 IV (not to exceed 2 mg/dose) on days 8 and 29; administer every 6 weeks for up to 6 cycles.

Grade 4

- Standard of care is surgical resection followed by EBRT (59.4 Gy to 60 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions) and temozolomide 75 mg/m2/day orally on days 1 to 42, usually 1 to 1.5 hours before radiation, followed by adjuvant temozolomide 6 cycles [7][10] OR

- Postradiation therapy: adjuvant temozolomide at higher doses of 150 to 200 mg/m2/day orally on days 1 to 5 every 28 days for 12 cycles is recommended.[11]

- Hematologic toxicity may be higher with concurrent treatment, with a higher incidence in women.

The phenomena of pseudoprogression after radiation therapy may be seen; this is the development of progressive enhancing lesions on MRI, representing radiation necrosis rather than active tumors.

Recommendations for recurrent tumors include reoperation, carmustine wafers, alternate chemotherapeutic regimens, and investigational IDH-targeted approaches. Re-radiation is rarely helpful; an additional 36 Gy in 18 fractions may be given. Bevacizumab, a humanized VEGF monoclonal antibody, has activity in recurrent glioblastoma, potentially increasing progression-free survival (PFS) and reducing peritumoral edema and glucocorticoid use.[12] IDH-targeted approaches, including vorasidenib and other small-molecule inhibitors of mutant IDH1 and 2 (ivosidenib, olutasidenib, safusedinib), are in trials. Vaccine strategies are also being explored. Recurrent glioblastoma treatment decisions must take into consideration factors such as previous therapy, time to relapse, performance status, and quality of life. Whenever possible, patients with recurrent disease should be enrolled in clinical trials.

Treatment Approaches

As with other malignancies, a multimodal treatment approach is undertaken, including surgical, medical, and radiation oncology. Low-grade astrocytomas: No clear superiority of any particular modality is known. As these low-grade tumors can be pretty indolent, questions arise about the risk-benefit ratio of undertaking any intervention. A study by Ishkanian et al demonstrated the efficacy of adjuvant radiotherapy for pilocytic astrocytoma (WHO grade 1); it prolongs PFS at 5 years and 10 years compared to observation.[13] Overall, survival was equal.

Grade 2 astrocytoma: radiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy are better than radiotherapy alone. Results from a trial showed that chemotherapy with vincristine, procarbazine, and lomustine following radiotherapy leads to better 10-year PFS (51% vs 21%).[14] Grade 3 astrocytomas: Multimodal therapy includes surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy (adjuvant temozolomide). Data regarding concurrent temozolomide is lacking, although some studies showed improved survival (46% vs 29%). IDH mutation is also associated with improved 5-year survival (79% vs 22%).[15] Response to chemotherapy is better in anaplastic astrocytomas than glioblastomas. In the event of recurrence, temozolomide shows a better response. Nitrosourea-treated recurrent tumors showed about 35% response with temozolomide. Moreover, 6-month survival rates were also better (46% vs 31%).[6] Adjuvant carmustine shows a slight survival benefit.

Other Medications

Prophylactically starting antiepileptics is controversial. Those who have a complaint of seizure should be started on antiepileptics. For seizures, the patient is usually started on levetiracetam, topiramate, lamotrigine, valproic acid, and lacosamide. These drugs interfere less with the hepatic microsomal enzyme system. Other drugs, such as phenytoin and carbamazepine, are used less frequently as they are potent enzyme inducers that can interfere with glucocorticoid metabolism and chemotherapeutic agents' metabolism.

Corticosteroids are also used because their anti-inflammatory action provides excellent symptomatic relief and decreases the mass effect. Dexamethasone is the glucocorticoid of choice because of its low mineralocorticoid activity. Initial doses are typically 12 to 16 mg/d in divided doses orally or intravenously (both are equivalent). Concurrent prophylaxis for gastrointestinal ulcers should be prescribed with corticosteroid administration.

Venous thromboembolic disease occurs in 20% to 30% of patients with high-grade gliomas and brain metastasis; hence, prophylactic anticoagulants should be used during hospitalization and in nonambulatory patients. Those who have had deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolus can safely receive therapeutic doses of anticoagulation without increasing the risk of hemorrhage into the tumor.

Differential Diagnosis

Before confirming a diagnosis of astrocytoma, it's crucial to consider other potential conditions that may present with similar symptoms or imaging findings. The differential diagnosis for astrocytoma includes the following:

- Glioblastoma multiforme

- Brain metastasis

- Brain abscess

- Oligodendroglioma

- Encephalitis

- Multiple sclerosis

- Primary central nervous lymphoma

- Toxoplasmosis

Surgical Oncology

Maximum safe resection is the preferred surgical approach. Surgery aims to remove or debulk the tumor. Histological diagnosis is made possible by the tissue biopsy provided by the surgeon. Other symptom-relieving procedures include intracranial tension-reducing procedures like ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunting and external ventricular drain insertion. Complete resection (>98% based on volumetric MRI) improves median survival compared with subtotal resection (13 months vs 8.8 months).[16] For low-grade gliomas, supratotal resection is also advocated (ie, removing tissue beyond the MRI-defined abnormalities), suggesting an increase in overall survival with this strategy.[17]

The urgency of neurosurgical evaluation depends on whether the patient is clinically stable, the symptoms' severity, and the tumor's size and location. Preoperative evaluation includes MRI and diffusion tensor imaging.

Intraoperative techniques

- In a multicenter trial including 314 patients who underwent resection of a newly diagnosed glioblastoma, the complete resection rate was similar for intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging (iMRI) or 5-aminolevulinic acid (81% and 78%, respectively).[18]

- In a trial of iMRI versus conventional neuronavigation, iMRI use led to better PFS.[19]

Timing of surgery

- Large tumors with significant symptoms: immediate

- Small tumors with minimal symptoms: immediate (preferred) or delayed [20]

Medical Oncology

Antineoplastic Agents

Temozolomide is an oral alkylating agent converted to 3-methyl-(triazen-1-yl)imidazole-4-carboxamide (MTIC) at physiologic pH. This agent is 100% bioavailable, and approximately 35% crosses the blood-brain barrier. Based on the CATNON trial, adjuvant treatment consists of 12 monthly cycles, beginning 1 month after radiotherapy completion. The first cycle dose is 150 mg/m2, followed by 200 mg/m2 orally for 5 days in a 28-day cycle. Temozolomide is moderately emetogenic; hence, antiemetic prophylaxis is required with 5-HT3 antagonists. The Procarbazine, Lomustine, and Vincristine (PCV) regimen involves a 6- to 8-week cycle length for 6 cycles. Eight-week cycles may be preferred for grade 2 tumors.[21] mTOR inhibitors are also proposed for the treatment of grade 1 astrocytomas.

Staging

Staging is not performed in patients with astrocytoma. Grading only is determined, as described previously, which is a determinant of prognosis.

Prognosis

Understanding the prognosis of astrocytomas is essential for guiding treatment decisions and providing realistic expectations to affected patients and their families.

Typical survival ranges are as follows:

- WHO grade 2 astrocytomas - less than 5 years

- WHO grade 3 astrocytomas - about 2 to 5 years

- WHO grade 4 astrocytomas - approximately 1 year

Prognosis is favorable for low-grade tumors, with survival times approaching 7 to 8 years post-surgery. In anaplastic astrocytoma, therapy focuses on improving symptoms. Radiotherapy of partially resected tumors increases postoperative survival rates. Survival rates after postsurgical radiation therapy are nearly double those of only surgical intervention (5 vs 2.2 years).

Genetics also determines the prognosis of a particular tumor. Oligodendroglioma with Ch 1p19q changes responds better to PCV. Genetics is emerging as a pivotal field in the development of personalized tumor therapies.

Kallikrein levels are associated with patient prognosis:

- Increased kallikrein-related peptidases, KLK6 / KLK7-IR, leads to poor outcomes

- Immunoreaction with KLK6/9 decreased survival [22]

Complications

Managing astrocytoma cases can be fraught with numerous complications that can significantly impact outcomes and quality of life. Neurosurgical interventions, while often necessary for tumor resection, carry risks such as infection, bleeding, and neurological deficits due to damage to surrounding brain tissue. Postsurgical complications can include cerebral edema and seizures. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy, although critical for controlling tumor growth, can lead to adverse effects like fatigue, nausea, cognitive decline, and myelosuppression, increasing the risk of infections and anemia.

Efficient drugs have been devised to manage these complications properly. Long-term complications may involve radiation necrosis, secondary malignancies, and progressive neurological deterioration. Additionally, the tumor's location and infiltrative nature can make complete resection challenging, leading to recurrence and requiring ongoing treatment. Managing these complications necessitates a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to balance effective tumor control with the mitigation of adverse effects, emphasizing the importance of supportive care and regular monitoring to address issues promptly.

Consultations

Effectively managing astrocytomas cases involves consultations with various specialists to provide comprehensive care. This collaborative approach may involve consultations with the following:

- Neuro-oncologists and neurosurgeons are essential for evaluating the tumor and planning surgical interventions.

- Radiation oncologists and medical oncologists develop and administer appropriate radiotherapy and chemotherapy regimens.

- Neurologists are crucial for managing neurological symptoms and monitoring disease progression.

- Pathologists play a key role in diagnosing the specific tumor type and grade through histological and molecular analysis.

- Support from palliative care specialists is important for managing pain and improving quality of life, especially in advanced cases.

- Rehabilitation specialists, including physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech therapists, help address functional impairments and improve patient independence.

- Psychologists or psychiatrists provide essential mental health support, addressing the emotional and cognitive impacts of the disease.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and patient education are pivotal in managing astrocytoma, focusing on both prevention and empowerment through knowledge. While specific causative factors for astrocytoma are largely unknown, minimizing exposure to known risk factors such as ionizing radiation is advisable. Patient education involves providing comprehensive information about the disease, its symptoms, and the importance of early detection and regular monitoring. Educating patients about the potential signs of astrocytoma, such as persistent headaches, seizures, and neurological changes, can lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment.

Furthermore, empowering patients with knowledge about their treatment options, potential side effects, and strategies for managing symptoms can improve adherence to treatment plans and enhance quality of life. Effective patient education also includes discussions about lifestyle modifications, nutritional guidance, and psychosocial support, helping patients navigate their journey with astrocytoma more confidently and proactively.

Pearls and Other Issues

Clinical pearls emphasize the importance of a holistic approach to treating astrocytomas, leveraging the latest advancements in diagnosis and treatment as follows:

- Recognize early symptoms such as persistent headaches, seizures, and focal neurological deficits for prompt evaluation.

- Effective management involves a team of neuro-oncologists, neurosurgeons, radiation oncologists, neurologists, pathologists, and rehabilitation specialists.

- Utilize molecular diagnostics, including IDH mutation status, to inform prognosis and guide treatment strategies.

- Aim for maximal safe resection to reduce tumor burden and improve outcomes while minimizing neurological deficits.

- Combine surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy for optimal management tailored to the patient's specific tumor characteristics.

- Address symptoms proactively with medications for seizures, pain management, and corticosteroids to reduce cerebral edema.

- Implement routine imaging follow-ups to detect tumor recurrence or progression early.

- Educate patients and families about the disease, treatment options, potential adverse effects, and the importance of adherence to the treatment plan.

- Provide access to psychosocial support and palliative care services to enhance quality of life, especially in advanced stages.

- Incorporate physical, occupational, and speech therapy to address functional impairments and improve patient independence.

- Consider enrolling eligible patients in clinical trials to access cutting-edge therapies and contribute to advancing treatment options.

- Offer genetic counseling for patients with a family history of brain tumors to assess potential hereditary risks.

- Encourage healthy lifestyle choices, including proper nutrition and exercise, and avoid known risk factors like ionizing radiation exposure.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effectively managing astrocytoma cases requires an interprofessional approach involving physicians, advanced care practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, psychologists, and other health professionals. Each team member must bring specialized skills and strategies to enhance patient-centered care, improve outcomes, ensure patient safety, and boost team performance. Early initiation of treatment after consultation with the oncology team comprising medical oncologists, surgical oncologists, anesthetists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, and pathologists is a must.[23]

Physicians and advanced care practitioners must utilize advanced diagnostic skills and keep abreast of the latest treatment protocols, integrating evidence-based practices into patient care. Surgeons need precise technical skills for tumor resection, while radiologists and oncologists should be adept at interpreting imaging studies and developing personalized radiation and chemotherapy plans. Nurses play a crucial role in monitoring patient status, managing symptoms, and providing emotional support. Pharmacists must ensure the safe and effective use of medications, addressing potential drug interactions and managing adverse effects. Implementing safety protocols, such as surgical checklists, medication reconciliation, and infection control measures, is essential. Pharmacists and nurses should collaborate to ensure the safe administration of therapies.

Coordinating care across different specialties is crucial for managing patients with astrocytomas. Care coordinators or nurse navigators can play an essential role in ensuring that appointments, treatments, and follow-ups are well-organized. Effective care coordination helps prevent gaps in care, reduces redundancy, and ensures patients receive timely and comprehensive treatment.

Clear and open communication among team members is vital. Regular case discussions facilitate the exchange of information and collaborative decision-making. Focusing on patient-centered care involves considering the patient's preferences, needs, and values. All team members should engage with patients and their families to understand their goals and concerns, providing education and support throughout the treatment journey. Shared decision-making empowers patients and fosters a collaborative approach to care.

An interprofessional team is crucial in caring for patients with astrocytoma because it integrates diverse expertise from various healthcare disciplines, ensuring comprehensive and coordinated care that addresses all aspects of the patient's condition. Simulation exercises, quality improvement initiatives, and continuous professional development help teams stay cohesive and effective. Team performance can be enhanced through regular interdisciplinary meetings, effective communication strategies, and continuous professional development, fostering collaboration and improving patient outcomes.