Continuing Education Activity

The word "atelectasis" is Greek in origin; It is a combination of the Greek words atelez (Ateles) and ektasiz (ektasis) meaning "imperfect" and "expansion" respectively. It is caused by the partial or complete, reversible collapse of the small airways resulting in an impaired exchange of CO2 and O2 - i.e., intrapulmonary shunt. The incidence of atelectasis in patient's undergoing general anesthesia is 90% This activity discusses the etiology, epidemiology, evaluation, and treatment of atelectasis. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of teamwork among all involved caregivers to ensure adequate patient education, prevention, early recognition, treatment, and, ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Objectives:

- Review the various mechanisms by which atelectasis occurs.

- Identify the risk factors for developing atelectasis.

- Discuss the typical presentation of atelectasis, including history and physical.

- Explain the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to ensure patient education on atelectasis, early application of preventative strategies, and prompt diagnosis/ treatment of atelectasis.

Introduction

The word "atelectasis" is Greek in origin; It is a combination of the Greek words atelez (ateles) and ektasiz (ektasis) meaning "imperfect" and "expansion" respectively. It results from the partial or complete, reversible collapse of the small airways leading to an impaired exchange of CO2 and O2 - i.e., intrapulmonary shunt. The incidence of atelectasis in patient's undergoing general anesthesia is 90%.[1]

Etiology

The mechanism by which atelectasis occurs is due to one of three processes: compression of lung tissue (compressive atelectasis), absorption of alveolar air (resorptive atelectasis), or impaired pulmonary surfactant production or function.[2]

Atelectasis can categorize into obstructive, non-obstructive, postoperative, and rounded atelectasis.

Nonobstructive atelectasis can further classify into compression, adhesive, cicatrization, relaxation, and replacement atelectasis. Compression atelectasis is secondary to increased pressure exerted on the lung causing the alveoli to collapse. In other words, there is a decreased transmural pressure gradient (transmural pressure gradient = alveolar pressure - intrapleural pressure) across the alveolus resulting in alveolar collapse. In an awake, spontaneously-ventilating patient, caudad excursion of the diaphragm during contraction causes a subsequent decrease in intrapleural pressure and alveolar pressure. The decrease in pressure allows for passive movement of air into the lungs. This process is inhibited by general anesthesia due to diaphragm relaxation. Patients lying supine have cephalad displacement of the diaphragm further decreasing the transmural pressure gradient and increasing the likelihood of atelectasis. Adhesive atelectasis is often the result of a surfactant deficiency or dysfunction as seen in ARDS or RDS in premature neonates. Surfactant functions to decrease alveolar surface tension and prevent alveolar collapse; therefore, any alterations to surfactant production and function often manifest as an increase in the surface tension of the alveoli leading to instability and collapse. Cicatrization atelectasis is often the result of parenchymal scarring of the lung, leading to contraction of the lung. Processes that lead to cicatrization atelectasis include tuberculosis, fibrosis, and other chronic destructive lung processes. Relaxation atelectasis involves the loss of contact between parietal and visceral tissue as seen in pneumothoraces and pleural effusions. Replacement atelectasis is one of the most severe forms and occurs when all of the alveoli in an entire lobe are replaced by tumor. This is typically seen in bronchioalveolar carcinoma and results in complete lung collapse.

Obstructive atelectasis is often referred to as resorptive atelectasis and occurs when alveolar air gets absorbed distal to an obstructive lesion. The obstruction either partially or completely inhibits ventilation to the area. Perfusion to the area is maintained; however, so gas uptake into the blood continues. Eventually, all of the gas in that segment will be absorbed and, without return of ventilation, the airway will collapse. Resorption atelectasis can be secondary to numerous pathologic processes, including intrathoracic tumors, mucous plugs, and foreign bodies in the airway. Children are especially susceptible to resorption atelectasis in the presence of an aspirated foreign body because they have poorly developed collateral pathways for ventilation.

In contrast, adults with COPD have extensive collateral ventilation secondary to airway destruction and thus are less likely to develop resorption atelectasis in the presence of an obstructing lesion (i.e., intrathoracic tumor). The use of high inspiratory oxygen concentration (high FiO2) during induction and maintenance of general anesthesia also contributes to atelectasis via absorption atelectasis. Room air is 79% nitrogen; nitrogen is slowly absorbed into the blood and therefore helps maintain alveolar patency. In contrast, oxygen is rapidly absorbed into the blood.

Postoperative atelectasis typically occurs within 72 hours of general anesthesia and is a well-known postoperative complication.

Rounded atelectasis is less common and often seen in asbestosis. The pathophysiology involves the folding of the atelectatic lung tissue to the pleura.

While all of the mechanisms mentioned above may contribute to the formation of perioperative atelectasis, absorption and compression mechanisms are the two most commonly implicated.[3]

Middle lobe syndrome involves recurrent or fixed atelectasis of the right middle lobe and lingula. Extraluminal and intraluminal bronchial obstruction can result in middle lobe syndrome. Nonobstructive causes include inflammatory processes, defects in bronchial anatomy, and collateral ventilation. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage are the treatment of choice for this syndrome. Long term consequences of chronic atelectasis include bronchiectasis. Sjogren syndrome has associations with middle lobe syndrome and treatment with glucocorticoids has been favorable.

Epidemiology

Atelectasis does not preferentially affect either sex. There is also no increased incidence of atelectasis in patients with COPD, asthma, or increased age.[4] It is more common in patient's who recently underwent general anesthesia, with the incidence being as high as 90% in this patient population.[1] Research has shown that atelectasis appears in the dependent regions of both lungs within five minutes of induction of anesthesia.[5] Atelectasis is more prominent after cardiac surgery with cardio-pulmonary bypass than after other types of surgery, including thoracotomies; however, patients undergoing abdominal and/or thoracic procedures are at increased risk of developing atelectasis.[3] Obese and/or pregnant patients are more likely to develop atelectasis due to cephalad displacement of the diaphragm (see the section on epidemiology).

Pathophysiology

Administration of general anesthesia, use of muscle relaxants, obesity, pregnancy, inadequate pain control, and thoracic or cardiopulmonary procedures increase the risk of developing atelectasis in the perioperative period.

The incidence of atelectasis in patient's undergoing general anesthesia is 90%.[1] Studies have demonstrated that up to 15 to 20% of the lung at its base collapses during uneventful anesthesia before any surgical intervention. Atelectasis is seen with general anesthesia regardless of whether or not muscle paralysis is used. Ketamine, when used as a sole agent, is the only anesthetic agent that does not increase the risk for developing atelectasis.[6] The use of high inspiratory oxygen concentration (high FiO2) during induction and maintenance of general anesthesia also contributes to atelectasis via absorption atelectasis.

Obese patients have an increased incidence of atelectasis due to decreased FRC (functional residual capacity) and compliance. Atelectasis development in pregnant patients is by this same mechanism.

Inadequate pain control can contribute to the development of atelectasis by inducing shallow breathing ("splinting") and/or inhibiting coughing.

History and Physical

Typically, atelectasis is asymptomatic. However, a patient might also present with decreased or absent breath sounds, crackles, cough, sputum production, dyspnea, tachypnea, and/or diminished chest expansion.

Evaluation

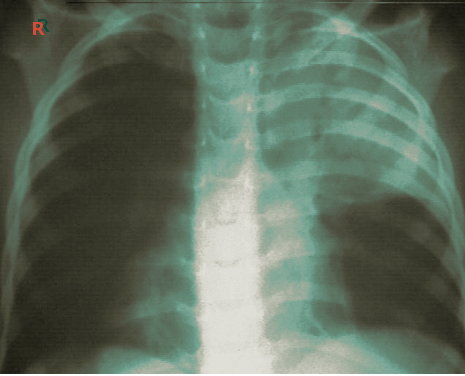

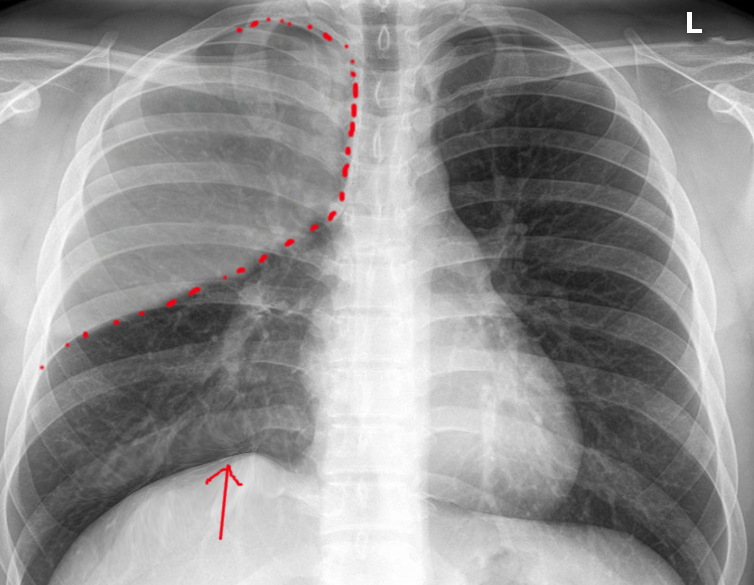

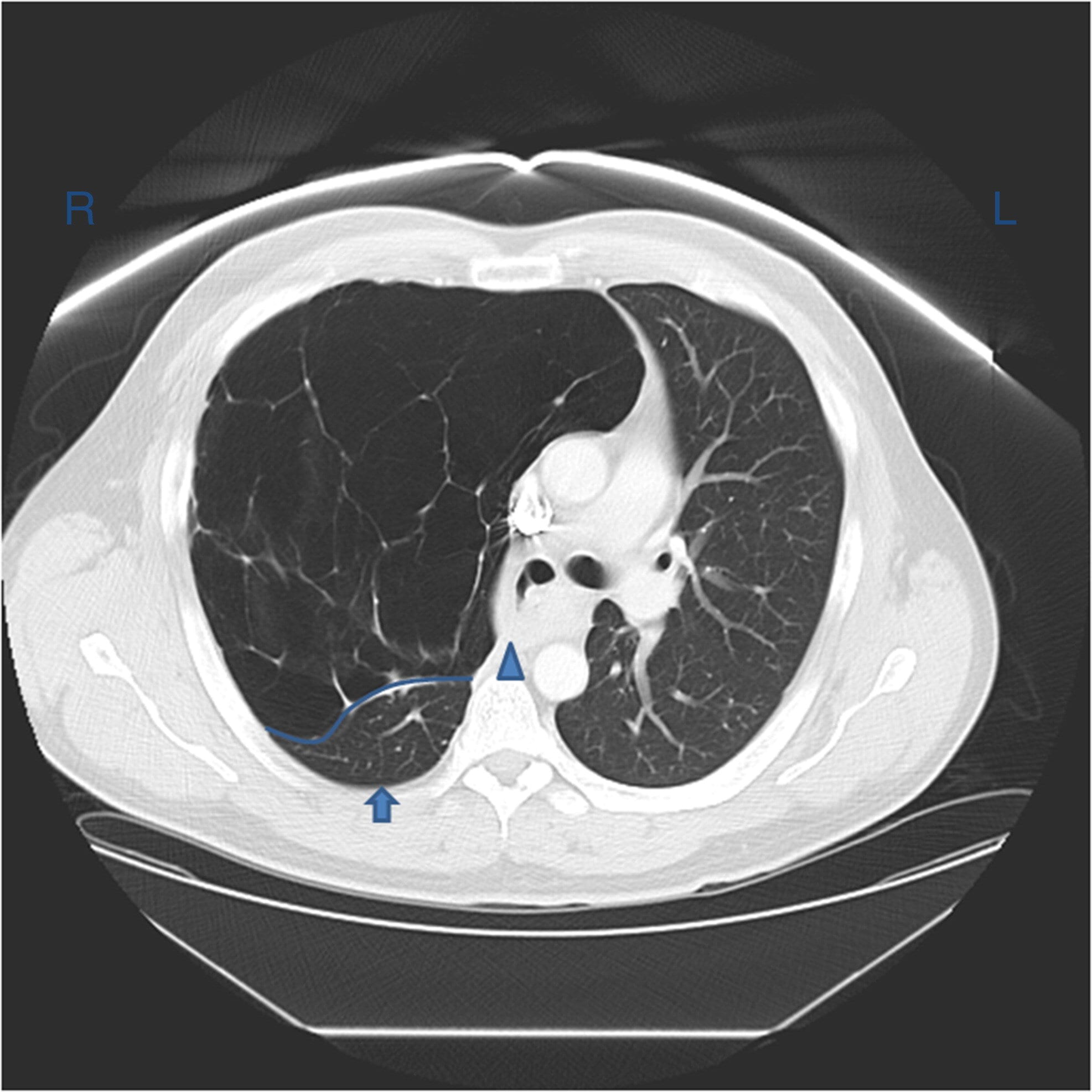

Atelectasis is usually a clinical diagnosis in a patient with known risk factors. If imaging is warranted, a chest X-ray, chest CT, and/or thoracic ultrasonography are useful in the diagnosis of atelectasis. A chest x-ray will reveal platelike, horizontal lines in the area of atelectatic lung tissue. Atelectasis is not typically evident on convention chest radiographs until it is significant.

On chest X-ray, atelectasis will result in the displacement of interlobar fissures, pulmonary opacification, and/or tracheal shift toward the affected side.[7]

Chest CT often reveals dependent lung densities and loss of volume in the affected side of the chest.

Atelectasis may also be directly visible with fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy can be both diagnostic and therapeutic, often revealing the cause of any obstruction contributing to the atelectasis (i.e., tumor, mucous plug, or foreign body).

An arterial blood gas may reveal arterial hypoxemia and respiratory alkalosis. The PaCO2 is often normal; however, it may be lower secondary to increased minute ventilation, which often accompanies atelectasis.

Treatment / Management

Most atelectasis that appears during general anesthesia leads to transient lung dysfunction that resolves within 24 hours after surgery. Nevertheless, some patients develop significant perioperative respiratory complications that can lead to increased morbidity and mortality if not treated. Atelectasis is preventable through avoidance of general anesthesia, early mobilization, adequate pain control, and minimizing parenteral opioid administration. When general anesthesia use is unavoidable, the use of continuous positive airway pressure, the lowest possible FiO2 during induction and maintenance, PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure), lung recruitment maneuvers, and low tidal volumes will help prevent the development of atelectasis.[8] One study showed that intraoperative alveolar recruitment with a vital capacity maneuver followed by PEEP 10 cm H2O is effective at preventing lung atelectasis in morbidly obese patients; this also correlated with better oxygenation, shorter PACU stay, and fewer pulmonary complications in the postoperative period.[9]

Changing position from supine to upright increases FRC and decreases atelectasis.[10] Encouraging patients to take deep breaths, early ambulation, incentive spirometry, use of an acapella device, chest physiotherapy, tracheal suctioning (in intubated patients), and/or positive pressure ventilation has been shown to decrease atelectasis. The mechanism behind all of these measures is a transient increase in transmural pressure that allows for reexpansion of collapsed lung segments. Prophylactic measures, such as incentive spirometry, should be taught and instituted before surgery and continued on an hourly basis following surgery until discharge to obtain the maximal benefit.

Additional pharmacologic treatment options include mucolytic agents (acetylcysteine) and recombinant human DNase (dornase alpha) in patients with cystic fibrosis. The aforementioned nebulized medications are particularly beneficial in patients with atelectasis secondary to mucous plugging of the airways.

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy also has a role in the management of atelectasis. In one study single-suction, fiberoptic bronchoscopy led to improved lung function and reversal of atelectasis in 76% of cases. Bronchoscopy should always be the intervention when there is a high suspicion for a mechanically obstructed bronchus and coughing/suctioning have not been successful. Bronchoscopy is also indicated when less invasive efforts, such as early ambulation, incentive spirometry, bronchodilators, and humidity, have not been successful within 24 hours of their initiation.

Employing early preventative strategies and valuing prompt recognition/diagnosis will not only improve patient outcomes, but it will also significantly decrease cost.[11]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of atelectasis should include the following:

- Neoplasm

- Pneumonia

- Pleural effusion

- Pulmonary embolism

- Foreign body

Prognosis

For patients with atelectasis, the prognosis varies greatly, and the primary determination is the underlying etiology and patient co-morbidities.

Complications

Atelectasis is one of the most common respiratory complications in the perioperative period, and it may contribute to significant morbidity and mortality, including the development of pneumonia and acute respiratory failure.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative fever has historically been attributed to atelectasis, but there is no evidence supporting the finding that atelectasis is a causative mechanism for fever.[12]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The definition of atelectasis is a partial collapse of the lung. It can cause people to feel short of breath. It can be a consequence of several different processes, most commonly when there is a poor inspiratory effort, an obstruction blocking airflow into the lung, extra pressure exerted on the outside of the lung, or deficient production or function of a specific protein in the lung. Treatment aims at the underlying cause of the condition, but mainly involves supportive measures, such as deep breathing exercises, incentive spirometry, and supplemental O2.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Prevention of atelectasis is vital to improving patient outcomes in the postoperative period. Despite employing these strategies, atelectasis is not always preventable and, therefore, early recognition and treatment are equally important. Ultimately, this will decrease the length of hospital stay, cost, and improve patient outcomes.

Both prevention and treatment of atelectasis need to be an interprofessional team effort. Physicians, and especially surgeons and anesthesiologists, need to be aware of the role of anesthesia in atelectasis. Nursing will be monitoring the patient both during and after the procedure. In the event of medical management, the pharmacist can provide recommendations on opioids and mucolytics. The nursing staff will be administering these and can report to the physicians on the effectiveness of therapy as well as any adverse events, which may lead to dose or agent changes, or other interventions. The nursing staff should assist the clinicians in the education of the patient and family in incentive spirometry and other techniques to minimize risk. In summary, atelectasis management needs to be an interprofessional team collaboration to optimize patient outcomes. [Level V]