Continuing Education Activity

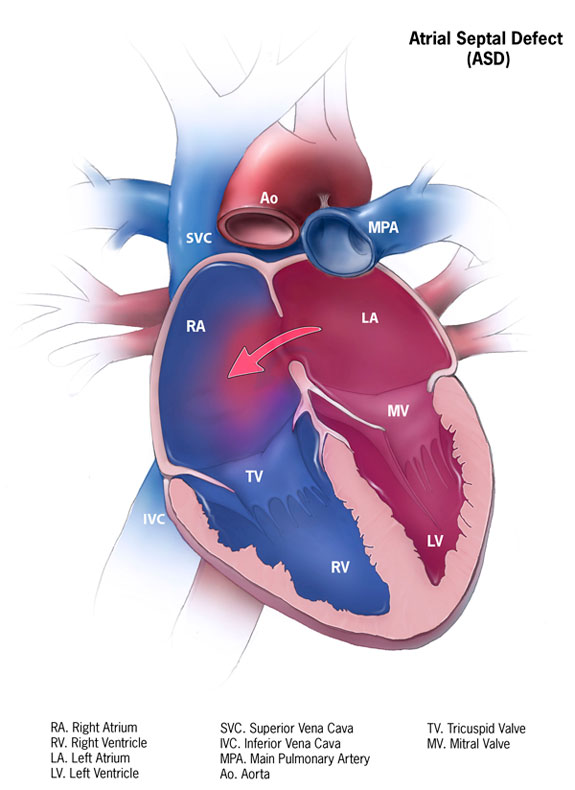

Atrial septal defect (ASD) is one of the most common types of congenital heart defects, occurring in about 25% of children. An atrial septal defect occurs when there is a failure to close the communication between the right and left atria. It encompasses defects involving both the true septal membrane and other defects that allow for communication between both atria. There are five types of atrial septal defects ranging from most frequent to least: patent foramen ovale, ostium secundum defect, ostium primum defect, sinus venosus defect, and coronary sinus defect. Small atrial septal defects usually spontaneously close in childhood. Large defects that do not close spontaneously may require percutaneous or surgical intervention to prevent further complications such as stroke, dysrhythmias, and pulmonary hypertension. This activity describes the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of atrial septal defect and highlights the role of team-based interprofessional care for affected patients.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of atrial septal defect.

- Outline the presentation of a patient with atrial septal defect.

- Describe the treatment and management options available for atrial septal defect.

- Explain the interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication regarding the management of patients with atrial septal defect.

Introduction

Atrial septal defect (ASD) is one of the most common types of congenital heart defects, occurring in about 25% of children.[1] An atrial septal defect occurs when there is a failure to close the communication between the right and left atria. It encompasses defects involving both the true septal membrane and other defects that allow for communication between both atria. There are five types of atrial septal defects ranging from most frequent to least: patent foramen ovale, ostium secundum defect, ostium primum defect, sinus venosus defect, and coronary sinus defect.[2] Small atrial septal defects usually spontaneously close in childhood. Large defects that do not close spontaneously may require percutaneous or surgical intervention to prevent further complications such as stroke, dysrhythmias, and pulmonary hypertension.

Etiology

Though atrial septal defects occur as singular defects, ASDs are associated with Mendelian inheritance, aneuploidy, transcription errors, mutations, and maternal exposures. Atrial septal defects are noted in patients with Down syndrome, Treacher-Collins syndrome, Thrombocytopenia-absent radii syndrome, Turner syndrome, and Noonan syndrome; these syndromes occur as a result of Mendelian inheritance. Maternal exposure to rubella and drugs, such as cocaine and alcohol can also predispose the unborn fetus to develop an ASD. Additionally, ASDs have been associated with familial genetic disorders and conduction defects. Transcription factors important during the atrial septation include GATA4, NKzX2-5, and TBX5. Holt-Oram syndrome ("heart-hand" syndrome) commonly characterized by a congenital heart defect (ASD in 58% of patients or VSD in 28% of patients), dysrhythmias and upper limb malformations usually involving the hands are associated with TBX5 mutations.[3] Mutations in the NKX2-5 gene have been associated with congenital heart disease (ASD and Tetralogy of Fallot), AV blocks, and juvenile sudden cardiac death.[3]

Atrial septal defects occur with other congenital heart defects (i.e., ventricular septal defects). In some patients with congenital heart disease, communication between the left and right heart circulations is crucial for survival. Patients with tricuspid atresia, transposition of the great vessels, variants of hypoplastic left heart syndrome, pulmonic/ tricuspid atresia with hypoplastic right heart, transposition of the great vessels, and total anomalous pulmonary venous return require the alternate blood flow that an ASD provides to survive the primary lesion until a more definitive solution is provided.[4]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of congenital heart disease and ASDs has increased over the past 50 years. In the 1930s congenital heart disease was diagnosed in less than 1 per 1000 live births. In recent years, congenital heart disease is diagnosed in 9 per 1000 live births. Atrial septal defects were identified between 1945 and 1949 in less than 0.5 live births per 1000. More recent epidemiologic data suggest that ASDs occur in 1.6 per 1000 live births.[5] The noted increase in prevalence is probably not due to an increase in disease as much as improvements in imaging modalities and training of practitioners. Several factors have been associated with the increased prevalence of congenital heart disease including advanced maternal age. Interestingly, economic and geographical differences have been noted in the diagnosis. Congenital heart disease is diagnosed more commonly in patients in developed countries who have higher incomes.[6]

Pathophysiology

Atrial septation begins during the fourth week of gestation.[7] Septation begins with the growth of the primary atrial septum (septum primum) from the roof of the primitive atrium caudally towards the endocardial cushions. The caudal end of the septum primum is covered by mesenchymal cells derived from the embryonic endocardium (the mesenchymal cap).[8] As the septum primum grows toward and attaches to the atrioventricular endocardial cushions, it closes and ultimately obliterates the ostium primum (the gap between the mesenchymal cap and the atrioventricular cushions). Once the leading edge of the septum primum attaches anteriorly to the atrioventricular cushions, the primitive atrium is divided into the right and left atria. The septum primum dorsally attaches to the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion. As the ostium primum closes, cell death occurs in the dorsal aspect of the septum primum, forming the ostium secundum.[8] The septum secundum forms from the roof of the atria to the right of the septum primum. As it grows caudally and partially covers the ostium secundum, the space created between the septum primum and the septum secundum creates the foramen ovale. In the fetus, the foramen ovale allows for oxygen rich blood to bypass the lungs by flowing directly from the right atrium to the left atrium. When the child is born and begins to breathe, the change in pulmonary vascular resistance and the resultant decrease in right atrial pressure that occurs allows for the septum primum to close the foramen ovale.

As the patent foramen ovale is a subclass of the ostium secundum defect, it is not a defect of the "true septum." The patent foramen ovale is the most common septal anomaly and occurs when ends the septum primum, and the septum secundum do not approximate and close the foramen ovale after the child breathes its first breath. The 4 types of atrial septal defects are[2]:

- Ostium secundum defect: This defect occurs when there is increased reabsorption of the septum primum in the atrium's roof, or the septum secundum does not occlude the ostium secundum. Ostium secundum defects are associated with pediatric syndromes such as Noonan, Treacher-Collins, and thrombocytopenia-absent radii syndrome.[8]

- Ostium primum defect: The third most common defect of the atrial septum that occurs due to the failure of the septum primum to fuse with the endocardial cushions. Ostium primum defects result in atrioventricular communications and are best considered among the spectrum of atrioventricular septal defects.[8]

- Sinus venosus defect: Superior and inferior defects occur, and neither involves the true membranous septum.

- Superior defect: This occurs when the orifice of the superior vena cava overrides the atrial septum above the oval fossa (the remnant of the foreman ovale) and drains both the left and right atria. The superior sinus venosus defect and a partial anomalous connection of the right superior pulmonary vein to the superior vena cava often occur together.[8]

- Inferior defect: This occurs when the orifice of the inferior vena cava overrides both atria. The inferior sinus venosus defect and an anomalous connection of the right inferior pulmonary vein to the inferior vena cava can occur together. [8] The inferior defect is less common than the superior defect.

- Coronary sinus defect: The coronary sinus is a vessel that runs along the groove between the left atrium and left ventricle and collects veins that represent the venous return of the heart muscle. It normally drains into the floor of the right atrium above the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve. A defect or hole in the common wall between the left atrium and the coronary sinus (called "unroofing" of the coronary sinus) creates a communication between the right and left atria.

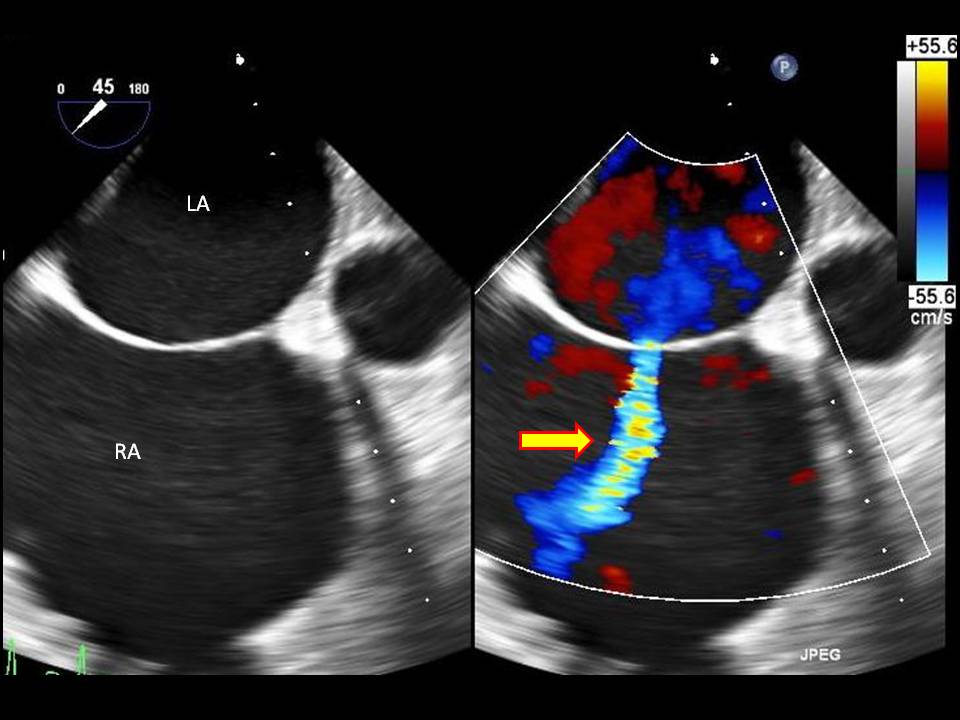

Normally, the pressure in the right atrium is significantly lower than the left atrium; therefore, blood flows from the left atrium to the right atrium causing a left-to-right shunt. The size of the defect determines how significant the shunt is. Significant shunts have a ratio of pulmonary (Qp) to systemic flow (Qs) that is greater than 1.5:1 (Qp/Qs > 1.5).[4] Chronic volume overload due to high pulmonary blood flow causes remodeling of the pulmonary vasculature. As pulmonary vessels remodel, the layer of smooth muscle increases in the vascular wall. Because the muscle layer in the vascular wall increases, resistance to flow in the pulmonary circuit increases. Due to the increased vascular resistance and pulmonary pressures increase, and pulmonary hypertension develops. Once pulmonary pressures equal systemic pressures, the shunt across the ASD reverses, and deoxygenated blood flows into the left atrium and systemically. When the reversal of the shunt across an ASD occurs due to pulmonary hypertension, a condition known as Eisenmenger syndrome develops.

History and Physical

Atrial septal defects are frequently asymptomatic. The characteristic murmur is a soft, systolic ejection murmur over the pulmonic area (second intercostal space) combined with a wide, fixed splitting of S2.[9] Many ASDs go undiagnosed until adulthood; therefore, treatment, especially of large defects, is often delayed. Untreated large defects can cause exercise intolerance, cardiac dysrhythmias, palpitations, increased incidence of pneumonia, pulmonary hypertension and increased mortality.[10] Eisenmenger syndrome is a rare, but severe complication of untreated ASDs due to vascular remodeling caused by chronic over flow (through a left-to-right shunt). As the vascular resistance increases right atrial pressures approach systemic. When right atrial pressures exceed systemic pressures, there is a reversal of shunt flow. Clinically Eisenmenger syndrome patients develop chronic cyanosis, increased pulmonary vascular resistance, dyspnea on exertion, syncope, and increased susceptibility to infection.[11]

Patients with smaller heart defects (less than 5 mm) might not develop any symptomology while patients with defects ranging between 5 to 10 mm will present in the fourth or fifth decade of life.[12] Patients with larger defects present sooner, in the third decade of life.[12] Patients may present with dyspnea, fatigue, exercise intolerance, palpitations or signs of right-sided heart failure. Approximately 20% of adult patients develop atrial tachydysrhythmias preoperatively. Evidence of stroke or transient ischemic attack especially following the diagnosis of a peripheral blood clot should raise suspicions for an ASD.

Evaluation

Diagnostic imaging is important in determining the size of the defect and is crucial in determining treatment options. A transthoracic echocardiogram is the gold standard imaging modality. A transthoracic echocardiogram allows one to detect the size of the defect, understand the direction of blood flow, find associated abnormalities (involvement of the endocardial cushions and atrial-ventricular valves), examine the heart for structure and function, estimate pulmonary artery pressure, and estimate the pulmonary/systemic flow ratio (Qp/Qs).[12] A transesophageal echocardiogram is a better tool for diagnosing the rarer cardiac defects.

Though echocardiography is the gold standard for evaluation of ASDs, other diagnostic modalities include cardiac CT and MRI. Both CT and MRI examine structures surrounding the heart and in the thoracic cavity. Chest x-ray findings are not as helpful diagnostically, though the chest x-ray assists providers to monitor clinical status by identifying cardiomegaly and pulmonary artery enlargement. Exercise testing can help determine the reversibility of shunt flow and the response of patients with pulmonary artery hypertension to activity.[12] Cardiac catheterization is contraindicated in patients who are young and present with small, uncomplicated ASDs.[12]

Treatment / Management

Patients with atrial septal defects less than 5 mm in size frequently experience spontaneous closure of the defect in the first year of life. Defects that are greater than 1cm will most likely require medical/surgical intervention to close the defect.[13] Patients presenting with atrial dysrhythmias initially require control of the abnormal rhythm and anticoagulation; definitive intervention can occur once the team gains control of the dysrhythmia.[14] Monitoring adult patients with small defects and no signs of right heart failure is appropriate. An echocardiography every 2 to 3 years evaluates right heart function and structure.[14] History of TIA or stroke requires more aggressive monitoring and possibly surgical intervention.

If an ASD requires closure, options include percutaneous and surgical intervention. Indications for treatment include stroke, a hemodynamically significant shunt greater than 1.5:1 and evidence of systemic oxygen desaturation.[15] Percutaneous transcatheter closure poses less risk for the patient, but it is only useful for the closure of ostium secundum defects. Percutaneous transcatheter ASD closure has a post-procedural complication risk of 7.2% compared to a post-surgical complication risk of 24%.[15] Complications associated with percutaneous closure risk include arrhythmias, AV blocks, cardiac erosion, and thromboembolism.[15] Contraindications to percutaneous closure are small hemodynamically insignificant ASDs, ostium primum defects, sinus venosus defects and coronary sinus defects, and secundum defects with advanced pulmonary hypertension.[15] When atrial septal defects are closed percutaneously, patients require antiplatelet therapy for the subsequent 6 months.[15] Women with large ASDs and Eisenmenger Syndrome should avoid pregnancy due to the risks of aggravating pulmonary artery hypertension that might be present and the increased occurrence of dysrhythmias.[14] Surgical closure of atrial septal defects requires the placement of a patch over the lesion through an incision in the right atrium.

In conclusion, atrial septal defects are common congenital heart defects and can range from clinically asymptomatic lesions to lesions that cause pulmonary hypertension, systemic cyanosis and vascular complications such as strokes. Most small defects will spontaneously close in the first year of life; however, large defects associated with significant systemic to pulmonary shunts and systemic oxygen desaturation require percutaneous of surgical intervention.

Differential Diagnosis

- Atrioventricular septal defect

- Ventricular septal defect

- Cyanotic congenital heart disease (sinus venosus defects and coronary sinus defects)

- Total anomalous pulmonary venous return

- Pulmonary stenosis

- Truncus arteriosus

- Tricuspid atresia

Complications

- Atrial dysrhythmias

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension

- Right-sided congestive heart failure

- Transient ischemic attack/stroke

- Eisenmenger syndrome

Pearls and Other Issues

- Atrial septal defects are one of the most common types of congenital heart defects and are present in about 25% of live births.

- The most common type of ASD is an ostium secundum defect.

- The transcutaneous percutaneous approach to ASD closure is only indicated in patients with ostium secundum defects. Surgical intervention is required for the ostium primum, sinus venosus, and coronary sinus defects.

- Transcutaneous percutaneous closure of ASD is contraindicated in patients with increased pulmonary hypertension.

- Dysrhythmias occurring due to ASDs are treated with cardioversion followed by anticoagulation. If cardioversion is not successful, rate control with medications and anticoagulation are necessary.

- Eisenmenger syndrome is a late complication of ASD that occurs secondary to pulmonary hypertension.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Improving healthcare team outcomes in patients with atrial septal defects requires an interprofessional team with strong input from the patient's pediatrician, primary care physician and nurse practitioner. In most cases, ASD is first diagnosed by the primary provider and the patient referred to the cardiologist.

Adults and children with atrial septal defects require consistent follow up with cardiologists to monitor the heart structure, heart function, and the patient's hemodynamic status.

Asymptomatic patients should be followed by the clinicians and the patient educated that elective closure will reduce the risk of pulmonary hypertension.

When a patient requires intervention, cardiac interventionists and thoracic surgeons with experience caring for children and adults with congenital heart disease provide the best outcomes for patients with congenital heart disease.[14] Monitoring with echocardiograms assesses the functional health of the heart and right heart function. Dysrhythmias require aggressive control. Pregnancy is not advised for women with large ASD and pulmonary hypertension.[14]

Due to the challenges of the disease, and family concerns, it is important for the nurse to assist with family education. The family must be taught about the signs and symptoms of complications and when the patient should return for further evaluation. The nurse should assist in making sure the patient has regular follow-up appointments. In followup after the procedure, the nurse should monitor the patient for changes in vital signs and any development of a new murmur or insidious unexplained fever. Open communication between the interprofessional team is recommended to ensure the best outcomes with minimal complications.

Outcomes

If the ASD is closed, the outcomes are excellent; however, if the ASD is not treated, patients may develop arrhythmias and pulmonary hypertension with poor outcomes.