Introduction

The basilar artery (Latin: arteria basilaris) contributes to the posterior component of the circle of Willis and supplies the contents of the posterior cranial fossa. It arises from the confluence of two vertebral arteries at the medullo-pontine junction, to ascend through the basilar sulcus on the ventral aspect of the pons. It provides arterial supply to the brainstem, cerebellum, and contributes to the posterior circulation through the posterior cerebral arteries. Clinical manifestations of basilar artery pathology include an impaired level of consciousness, cranial nerve deficits, cerebellar dysfunctions, and motor and sensory dysfunction. A cerebrovascular accident involving the basilar artery may result in characteristic clinical syndromes, notable among them are the “locked-in syndrome” and the “top-of-the-basilar syndrome.”[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

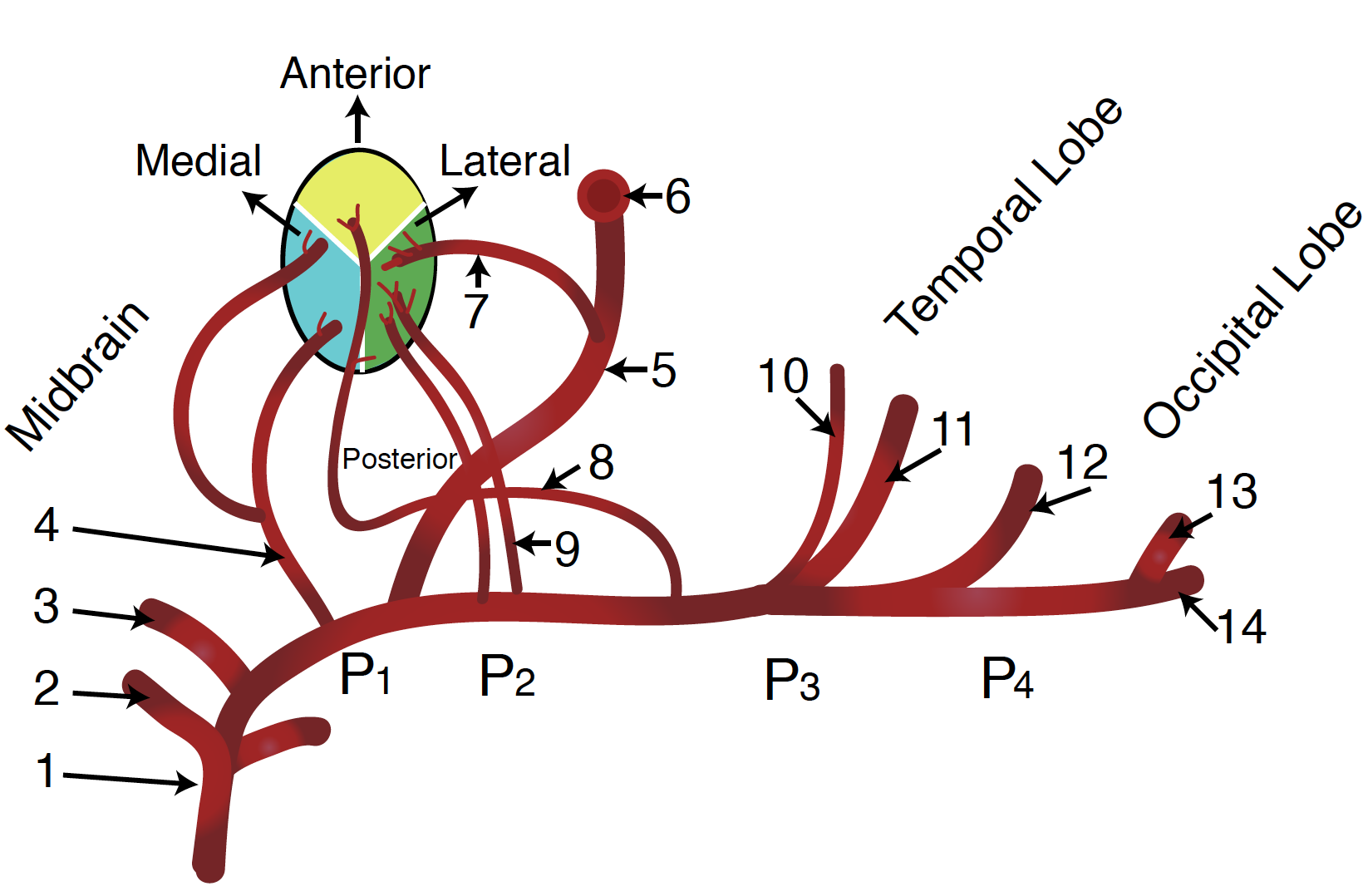

The basilar artery is a midline structure formed from the confluence of the vertebral arteries. Terminally, the basilar artery branches to establish the right and left posterior cerebral arteries. Along its course, the basilar artery gives off several branches. The pontine arteries are small perforating vessels that supply the pons. A portion of the circulation to the cerebellum also originates from the basilar artery. The paired anterior inferior cerebellar arteries (AICA) branch from the basilar artery inferiorly. The AICA supplies the inferior aspect of the cerebellum, including the inferior and middle cerebellar peduncles. The labyrinthine (internal auditory) artery is usually a branch of the AICA. (The posterior inferior cerebellar arteries originate from the vertebral arteries.) The paired superior cerebellar arteries branch from the basilar artery more superiorly, just prior to the terminal branching of the basilar artery into the right and left posterior cerebral arteries. The superior cerebellar arteries supply the superior aspect of the cerebellum, as the name would suggest.

Embryology

At around day 28 of embryonic life, the brain receives arterial supply from the primitive carotid artery via the carotid-vertebrobasilar anastomosis, formed by three longitudinal neural arteries (named after the accompanying nerves): the primitive trigeminal artery, the primitive hypoglossal artery and the primitive pro-atlantal artery.

This primitive anastomosis begins to disintegrate sequentially to pave the way for the definitive arterial circulation of the central nervous system (CNS).

On day 29 of gestation, the paired longitudinal neural artery on both sides of the hindbrain unite in the midline to form the basilar arterial plexus. The basilar arterial plexus communicates anteriorly and cranially via the posterior communicating arteries and caudally with the vertebral arteries.

During days 30 to 35 of gestation, the basilar artery, and vertebral arteries assume a more mature distribution and morphology. The basilar artery provides the posterior contribution to the circle of Willis via the posterior cerebral artery. The vertebral arteries continue as the paravertebral anastomosis of the cervical intersegmental arteries of C1 to C7.

Nerves

As the basilar artery courses through the basilar sulcus on the ventral aspect of the pons, it travels adjacent to the abducens nerve at the lower pontine border and the oculomotor nerve as it ascends more cranially.

Physiologic Variants

Some commonly documented variations in basilar artery distribution exist. One of these variations includes persistent carotid-basilar artery anastomosis. Several cadaveric studies put the incidence of this variation at less than 0.5%. A persistent trigeminal artery is the most commonly documented persistent carotid-basilar artery anastomosis, followed by the persistent hypoglossal artery. Other persistent carotid-basilar artery anastomoses are a persistent primitive optic artery and a persistent primitive pro-atlantal intersegmental artery. Another documented variation is a fenestrated basilar artery, wherein there are duplications of portions of the basilar artery. There is documentation of perforation of the basilar artery from autopsies, with a prevalence rate as high as 5%. This perforated variation predisposes to basilar artery aneurysm. The labyrinthine artery, also called the internal auditory artery, typically arises from the AICA but may arise from the basilar artery in about 15% of cases. A hypoplastic basilar artery is a very rare condition often seen alongside a persistent carotid-basilar artery anastomosis. The posterior inferior cerebellar artery, which is typically a branch of the vertebral artery, may arise from the basilar artery in about 10% of cases.[4][5][6]

Surgical Considerations

Surgical recanalization using stent-assisted angioplasty or traditional angioplasty is an option in the management of high-grade basilar artery stenosis with poor response to medical thrombolysis. However, varying mortality and morbidity rates following surgery remain a disincentive.

Clinical Significance

Basilar Artery Aneurysms

Basilar artery aneurysms account for about 5% of intracranial aneurysms. Symptoms vary with the size of an aneurysm. These include headaches, visual disturbances, nausea, vomiting, and loss of consciousness. Aneurysms of less than 15 mm may be asymptomatic. A basilar artery aneurysm may rupture, causing a subarachnoid hemorrhage; this may be heralded by a sudden and severe headache described as "thunderclap." The patient may describe it as the "worse headache of my life."[7]

Basilar Artery Thrombosis

Basilar artery thrombosis refers to a cerebrovascular accident or stroke due to occlusion of the basilar artery by a thrombus. The risk factors are similar to those in other occlusive cerebrovascular accidents. Implicated risks include atherosclerosis promoting factors like hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, obesity, diabetes, and coronary artery disease. Clinical manifestations often correspond to the level and degree of occlusion. Symptoms can include hemiparesis, quadriparesis, ataxia, dysphonia, dysarthria, oculomotor palsy, and abducens palsy. These may present as groups of signs and symptoms recognized as distinct clinical syndromes:

- "Top-of-the-basilar" syndrome involves occlusion in the rostral part of the basilar artery, resulting in ischemia affecting the upper brainstem and the thalamus. Clinical manifestations include behavioral changes, hallucinations, somnolence, visual changes, and oculomotor disturbances.

- Locked-in syndrome involves occlusion at the proximal and middle part of the basilar artery, sparing the tegmentum of the pons. The patient is thus conscious and oculomotor function is preserved, but other voluntary muscles of the body are affected. These patients cannot move or talk, but consciousness is evident because of vertical eye movement, which is an oculomotor nerve function.

- Pontine warning syndrome is a basilar artery atherosclerotic disease characterized by motor and speech disturbances that occur in a waxing and waning manner. These patients typically experience recurrent on-and-off attacks of hemiparesis and dysarthria. This syndrome is indicative of an imminent basilar artery branch occlusion with infarction of the supplied region.

Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency refers to a state of transient occlusion of the vertebrobasilar system. The resultant reversible ischemia manifests as temporary cerebellar or brainstem dysfunctions. Common symptoms include vertigo, diplopia, dysarthria, ataxia, confusion, and sudden fall due to knee weakness called a "drop attack." Vertebrobasilar insufficiency has the name "beauty parlor syndrome" after the early 1990s incidence of the syndrome increased in people who had hyperextended their necks at the washbasin for a prolonged time at the salon. The underlying pathology is chiefly an atherosclerotic pathology of the vertebrobasilar system, made only worse by hyperextension of the neck or a sudden change in position, especially from prolonged sitting to an erect position. This condition should not be confused with positional change associated with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).

Other Issues

MRI with angiography is the preferred imaging study for the vertebrobasilar circulation, as it affords a more sensitive delineation of areas of ischemia as well as areas of stenosis within the arteries.