Continuing Education Activity

The Bier block, also known as intravenous local anesthesia (IVRA), is a safe, effective, and cost-efficient way to provide short-term anesthesia and analgesia during surgery on an extremity. This technique requires minimal additional equipment and can be performed in a variety of clinical environments. This activity describes the indications, contraindications, and potential complications of the Bier block, and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients requiring it.

Objectives:

- Describe the pertinent anatomy involved in a Bier block.

- Outline the indications for a Bier block.

- Review the most-feared complication of the Bier block.

- Explain a structured, interprofessional team approach to provide effective care to and appropriate surveillance of patients undergoing a Bier block.

Introduction

In 1908, August Karl Bier published his first paper on intravenous anesthesia. Bier was known for his work with spinal anesthetics, and this technique was a natural offspring of his work with tourniquets and local anesthetics. The technique of exsanguinating an upper extremity and injecting local anesthetic was not met with the immediate accolade. It was not until it was reintroduced by Holmes in a 1963 paper, that it received popularity as a viable anesthetic technique. It has been noted that after this time there were numerous papers applauding this technique of intravenous local anesthesia (IVRA), otherwise known as the Bier Block. Since that time there have been numerous descriptions of this mode of anesthesia and analgesia along with innumerable adjuncts to local anesthetics. It has proven itself to be a useful anesthetic option for many upper or lower extremity surgeries of short duration. Those surgeries can include carpal tunnel release, Dupuytren contracture release, neuroma excision, fracture reduction, and any other surgery that can be performed reliably in less than 1 hour.[1][2][3][4][5]

Indications

The original attraction to IVRA is the simplicity of the block as well as the ability to perform the block with little additional equipment. It provides complete anesthesia, avoids general anesthetic, as well as a bloodless surgical field. It has also been noted to be a safe and reliable method of anesthesia. The original description of the Bier block included local anesthetic, large syringe, tourniquet, needle, and intravenous (IV) extension tubing. Other than the introduction of venipuncture with disposable plastic IV catheters, little has changed from the original technique. However, this does not mean that there have not been advancements or attempts to improve on the technique. [6][7][8][9]

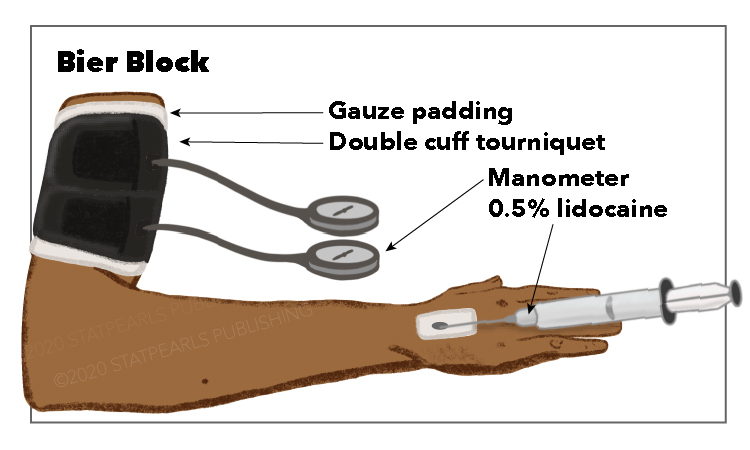

An essential step in the overall success of the Bier block is the exsanguination of the extremity before the injection of local anesthetic. After an IV is placed on the extremity to be anesthetized, it is common practice to place a proximal double–cuffed pneumatic tourniquet on that same extremity. The IV should be placed as close to the site of surgery or injury as possible. The dorsum of the hand is one of the more common sites for placement. Commonly, the extremity is elevated for 2-3 minutes to aid in passive venous drainage. Following this 2-3 minute period, a soft roll of gauze can be placed in the patient's hand to minimize discomfort while an Esmarch bandage is applied to exsanguinate the arm. Once it is wrapped above the level of the pneumatic tourniquet, the proximal cuff is inflated. At this point, a local anesthetic can be injected through the IV catheter. Caution must be taken not to inject the local anesthetic too quickly or with too much force to minimize the risk of leakage of the local anesthetic beyond the tourniquet into the systemic circulation. Once the local anesthetic (typically 40 ml of 0.5% Lidocaine) is injected, there may be visible blanching in various areas of the extremity. This blanching is thought to be due to any residual blood being forced toward the skin surface. Although this does not ensure a successful block, it is a positive indicator that analgesia will likely be adequate. The volume of administration can vary based on the potency of the local anesthetic used. It has been common practice to use 30-50 mL of 0.5% Lidocaine without epinephrine based on initial descriptions of the technique. Although Lidocaine is the most commonly used local anesthetic, others can be used to include prilocaine, ropivacaine, and chloroprocaine. One local anesthetic that is not recommended for IVRA is bupivacaine due to its high cardiac toxicity and potential for cardiac arrest. Whichever local anesthetic is used, it should be preservative-free to minimize the risk of thrombophlebitis and free of epinephrine. Regardless of the practitioner’s technique used, the total volume and concentration used should be less than the maximum recommended dose of the local anesthetic used to avoid LAST should there be tourniquet failure. Additionally, the tourniquet should remain inflated to two times the systolic blood pressure for at least 30 minutes before deflating. It is also general practice to either release the tourniquet incrementally or cyclically deflate the tourniquet.[10]

There have been studies that looked at the benefits of different tourniquet techniques. In a study looking at the volumetric comparison and venous pressure utilizing several techniques, they found that the Esmarch bandage was the most effective at exsanguination, although elevation with arterial compression and pneumatic splint provided significant reductions in limb volume. A more recent trend has been the use of a distal forearm tourniquet. These techniques describe placing a tourniquet just distal to the elbow with lower doses of local anesthesia required to obtain adequate anesthesia and analgesia. The use of forearm tourniquets has proven to be a safe and effective alternative to a proximal upper extremity technique but can also interfere with the surgical field if the tourniquet is too distal. The overall local anesthesia required can be reduced to approximately 25mL of Lidocaine compared to 40 mL with an upper extremity technique. NYSORA (New York Society of Regional Anesthesia) has also advocated for using only 12-15mL of 2% Lidocaine for an upper extremity block with a forearm tourniquet. An additional benefit of the forearm tourniquet is reduced tourniquet pain that has been shown to reduce sedation requirements with reduced need for PACU (Post-Anesthesia Care Unit) admission.

There are numerous studies that have evaluated additional adjunct medications that can be administered in a Bier block to include: opioids (fentanyl, morphine, meperidine, sufentanil), dexamethasone, clonidine, dexmedetomidine, tramadol, ketamine, muscle relaxants, anti-emetics, benzodiazepines, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDS). Opioids have not produced increased analgesia or anesthesia, with the exception of meperidine. Meperidine at doses of 30mg or more can provide some postoperative analgesia at the expense of nausea, vomiting, and dizziness. Dexamethasone has been used, along with ketorolac, and shown to be somewhat effective in reducing tourniquet pain and improving postoperative analgesia when compared to lidocaine alone. When added along with lidocaine, dexmedetomidine was superior to clonidine in the speed of onset of the sensorimotor blockade, prolongation of sensory recovery, while reducing intra-operative and post-operative pain scores. Clonidine has also proven to prolong tourniquet tolerance. Ketamine dosed at 50mg with lidocaine was shown to reduce the patient's request for additional intra-operative analgesia and provided better postoperative pain control. Muscle relaxants can improve the motor blockade of the block and aid in fracture reduction. Atracurium is the preferred muscle relaxant as it undergoes Hofmann elimination.[10] When dosed with lidocaine, midazolam at 50 mcg/kg, has been reported to reduce the time of onset of sensory and motor blockade compared to lower doses. Of all these potential adjuncts, NSAIDs (ketorolac in particular) along with clonidine, have the best evidence for improved post-operative pain control.

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications include patient refusal, hypersensitivity or allergy to local anesthetics, impaired perfusion of the limb, deep vein thrombosis or thrombophlebitis of the limb, uncontrolled hypertension, surgical procedures in a limb which cannot completely be exsanguinated, open wounds, or significant injuries to the limb

Relative contraindications include an uncooperative patient, obesity impacting the reliability of the blood pressure cuff on large extremities, neuropathies, arrhythmias, surgical procedures lasting over 2 hours, sickle cell disease, Paget's disease [10]

Complications

The Bier block is a very safe technique but the user should be aware that there are potential complications that can occur with this technique. According to the ASA Closed Claims Project from 1980-1999, there were only three reported cases of death or brain damage associated with IVRA. Some rare, but reported, severe adverse effects include local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST), preictal behavior, seizures, and cardiac arrest. Other less severe complications include the potential for nerve damage, compartment syndrome, skin discoloration or petechiae, and thrombophlebitis. The most common adverse event encountered during IVRA is tourniquet pain. The initial treatment, if using a double tourniquet, would be inflation of the distal tourniquet followed by deflation of the proximal cuff. This will generally provide increased patient comfort. If this is ineffective, additional sedative medications or alternate methods of providing analgesia may be required. [2][11]

Clinical Significance

In conclusion, the Bier block is a safe, effective, and cost-effective way to provide anesthesia and analgesia for extremity surgeries of short duration. This elegant technique requires minimal additional equipment and can be performed in a variety of clinical environments. Although the risk of LAST is extremely rare, it is still recommended to have therapeutic interventions available. Many adjuncts have been used to reduce tourniquet pain, improve sensorimotor blockade, and improve post-operative pain scores. Of those listed, ketorolac has the best evidence for providing postoperative pain relief.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The bier block may be done by a nurse anesthetist, anesthesiologist, pain specialist, or even an interventional radiologist. All healthcare workers who perform the Bier block should be aware of the potential complications. According to the ASA Closed Claims Project from 1980-1999, there were only three reported cases of death or brain damage associated with IVRA. Some rare, but reported, severe adverse effects include local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST), preictal behavior, seizures, and cardiac arrest. Other less severe complications include the potential for nerve damage, compartment syndrome, skin discoloration or petechiae, and thrombophlebitis. The most common adverse event encountered during IVRA is tourniquet pain. It is important always to have resuscitative equipment in the room where the procedure is being performed.