Continuing Education Activity

Blood transfusions are a relatively common medical procedure, and while typically safe, there are multiple complications that practitioners need to be able to recognize and treat. This activity reviews the indications for blood transfusion, including for special patient populations, the pre-transfusion preparation, and the potential complications of blood transfusions. In addition, this activity highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients undergoing blood transfusions.

Objectives:

- Identify the indications for blood transfusions.

- Describe the management of blood transfusion complications.

- Explain the importance of proper pre-transfusion preparation of donor blood to reduce the risk of complications.

- Review a structured interprofessional team approach to provide effective care to and appropriate surveillance of patients undergoing blood transfusion.

Introduction

Medicine has made significant progress in understanding circulation in the past few hundred years. For millennia medicine believed in the "four humors" and used bloodletting as a treatment. In the 1600s, William Harvey demonstrated how the circulatory system functioned. Shortly after that, scientists became interested in transfusion, initially transfusing animal blood into humans. Dr. Philip Syng Physick carried out the first human blood transfusion in 1795, and the first transfusion of human blood for treating hemorrhage happened in England in 1818 by Dr. James Blundell.[1] Rapid strides have been made in understanding blood typing, blood components, and storage since the early 1900s. This has developed into the field of transfusion medicine. Transfusion medicine involves laboratory and clinical medicine, and physicians from multiple specialties, such as pathology, hematology, anesthesia, and pediatrics, contribute to the field. Transfusion of red blood cells has become a relatively common procedure. In the United States, around 15 million units are transfused annually, while about 85 million units are transfused worldwide.[2][3][4]

Blood is typically stored in components. Fresh whole blood has always been thought of as the standard for transfusion; however, medical advancement has allowed the efficient use of the different components, such as packed red blood cells (PRBCs), individual factor concentrates, fresh frozen plasma (FFP), platelet concentrates, and cryoprecipitate. Consequently, current indications for whole blood transfusion are generally very few. The US military buddy transfusion system is the most widespread system of whole blood transfusion.[5] Additionally, whole blood transfusion in civilian pre-hospital settings and the trauma bay is seeing a resurgence in some regions. The hemoglobin in red blood cells binds oxygen and is the body's main source of oxygen delivery. A single unit of packed red blood cells is roughly 350 mL and contains about 250 mg of iron.

Indications

Guidelines on red blood cell transfusion from the American Association of Blood Banks advise a restrictive approach for stable patients with non-hemorrhaging anemia.[6] While there could be variations, anemia is usually defined as a hemoglobin level of less than 13 g/dL in males and less than 12 g/dL in females. While currently, a more restrictive threshold is used to determine the indication for transfusion, previously, a liberal strategy, typically using a cutoff of hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL, was used, regardless of symptoms.

Currently, guidelines for the transfusion of red blood cells (RBC) generally follow a restrictive threshold. While there is some variation in the number for the threshold, 7 g/dL is an agreed-upon value for asymptomatic healthy patients. Multiple studies have shown this is an acceptable threshold in other patient populations, including those with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and critically ill patients. The guidelines recommend a value of 8 g/dL as the threshold in patients with coronary artery disease or those undergoing orthopedic surgeries. However, this may be secondary to the lack of literature on using a threshold of 7 g/dL in the evaluation studies of these patient populations. The guidelines and clinical trials on transfusion requirements in critical care (TRICC) also recommend a value of 7 g/dl as the threshold for critically ill patients.[7][8][9][10]

Transfusion may also be indicated in patients with active or acute bleeding and patients with symptoms related to anemia (for example, tachycardia, weakness, dyspnea on exertion) and hemoglobin less than 8 g/dL.[11] Anemia, in such cases, is described as a decreased circulating red cell mass, defined as grams of hemoglobin per 100 ml of whole blood. Anemia may occur due to external loss, inadequate production, internal destruction, or a combination of these factors. While many patients experiencing active bleeding become anemic, anemia in itself does not become an indication for transfusion. The result of severe hemorrhage is a state of shock, and shock is the insufficient supply of oxygen to carry out cellular metabolism. Red cell mass repletion is one facet of the management of hemorrhagic shock.

Unless the patient is actively bleeding, it is recommended to transfuse 1 unit of packed red cells at a time, which will typically increase the hemoglobin value by 1 g/dL and hematocrit by 3%. Follow up by checking post-transfusion hemoglobin.[12]

The American Society of Anesthesiologists advises transfusion at hemoglobin levels of 6 g/dL or less. However, more recent data show decreased mortality with preanesthetic hemoglobin greater than 8 g/dL, especially in renal transplant patients.[13]

The transfusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) is common, but there are limited specific indications for its use. There is insufficient evidence for its use in many clinical scenarios, such as prophylaxis in nonbleeding patients.[14][15][16] FFP transfusion is sometimes indicated in bleeding patients to replace lost coagulation factors. Clinical situations fulfilling this criterion include cardiopulmonary bypass, massive transfusion, decompensated liver disease, extracorporeal pulmonary support techniques, or acute disseminated intravascular coagulation.

In the past, FFP, combined with vitamin K, was indicated for warfarin excess in cases of life-threatening hemorrhage. FFP is rarely needed in vitamin K deficiency or warfarin reversal because prothrombin complex concentrate is widely available.[17]The exception is in the cases of concomitant plasma volume deficit.

Platelet transfusion is beneficial in cases of platelet deficiency or dysfunction. In patients with bone marrow failure, prophylactic platelet transfusion is indicated when there are no other risk factors for bleeding and platelet counts are below 10 X 10/L. If other associated risk factors exist, the threshold to transfuse may be raised to 20 X 10/L. A prerequisite to invasive procedures is platelet counts greater than 50 X 10/L. In the case of active hemorrhage, platelet transfusion should be done when thrombocytopenia contributes to the hemorrhage, and the platelets are less than 50 X 10/L. When there is diffuse microvascular bleeding, the platelets should be maintained above 100 X 10/L.[18][19]

Cryoprecipitate transfusion is indicated in dysfibrinogenemia or fibrinogen deficiency in the setting of bleeding, injury, invasive procedures, or acute disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications, but some patients or their patients (in pediatric cases) may refuse to receive transfusions on religious grounds.[20] Whole blood transfusion is not indicated when component-specific treatment is available, such as using red blood cells to treat anemia or using fresh frozen plasma to treat coagulopathy. Whole blood transfusion could lead to many complications, for instance, volume overload, which is why it is advisable to use component therapy whenever possible.

Equipment

Blood products are transfused through intravenous tubing with filters. The filters, which typically have pore diameters of 170 to 260 microns, are also used to prevent particulate debris from being administered. However, the trapped particulate leads to bacterial growth, and the American Association of Blood Banks (AABB) advises against using a filter for more than four hours. Before transfusion, the tubing should be primed with an isotonic, calcium-free blood-compatible solution, for example, normal saline. Citrate is used as a preservative in packed red blood cells, and clots will form in the intravenous line if there is more calcium than the citrate can buffer.[21]

The suggested equipment required for a blood transfusion includes the following:

- Blood components or whole blood could be provided through various central venous access devices or peripheral intravenous catheters. The following sizes should be considered:

- 20-22 gauge for routine transfusion in adults

- 16-18 gauge for rapid transfusion in adults

- 22-25 gauge for pediatrics

- The requirements for administration sets might vary

- Blood filters

- The administration of platelet-poor plasmas requires supplies that often differ by product and brand.

- Infusion devices, such as infusion pumps, blood warmers, rapid infusers, and pressure devices, can be used to transfuse blood components.

- A pressure infusion device may be needed for the rapid transfusion of blood components.

- A blood warmer device is often needed to prevent hypothermia in the rapid administration of cold-blood components, for instance, in trauma settings or operation theatres.

Personnel

Two providers should verify blood products before administering, and patients should be monitored during transfusion by qualified personnel. Blood transfusions can be carried out by various healthcare providers, such as registered nurses, licensed vocational nurses, or licensed practical nurses. Nurses usually perform this task on the advice of a physician. Regarding blood transfusion training requirements, most professionals, such as registered nurses and licensed vocational nurses, learn how to carry blood transfusions through medical training and educational programs.

Preparation

Preparation for blood transfusion involves running pretransfusion testing for compatibility between recipient antibodies and donor red blood cells. This involves obtaining a sample of the recipient’s blood to send for a type and screen. The type and screen test verifies the recipient’s blood type and also determines if the recipient has any “unexpected” (non-ABO) antibodies that might cause a reaction. There are multiple methods for running this screen. If the screen is negative, it is very unlikely there will be a reaction. Obtaining blood for the patient should be done rapidly if required. If the screen is positive, many blood banks will crossmatch and hold two units of blood for the patient in case they need a transfusion. Another prerequisite to blood transfusion is to take consent from the patient if possible.[22]

The following is the list of important steps to follow before proceeding with blood transfusion:

Find Current Type and Crossmatch

- Take a blood sample, which lasts up to 72 hours

- Send the sample to the blood bank

- Ensure that the blood sample has the correct labeling with the date and timing

- Wait for the blood bank to crossmatch and prepare the needed units

Obtain Informed Consent and Health History[22]

- Discuss the procedure with the patient

- Confirm the past medical history and any allergies

- The supervising provider should have obtained signed consent from the patient

Obtain Large-bore Intravenous Access

- This is 18 gauge or larger IV access

- Each unit should be transfused within 2-4 hours

- A second IV access should be secured in case the patient needs additional IV medications

- Normal saline is the only fluid that can be administered with blood products

Assemble Supplies

- Y tubing with an in-line filter

- 0.9% NaCl solution

- Blood warmer

Obtain Baseline Vital Signs

- These include heart rate, temperature, blood pressure, pulse oximeter, and respiratory rate

- Respiratory sounds and urine output should also be documented

- Notify the provider if the temperature is more than 100 F

Obtain Blood from the Blood Bank

- Once the blood bank notifies that the blood is ready, its delivery from the blood bank should be ensured

- Packed red blood cells can only be given one unit at a time

- Once the blood has been released for the patient, there are 20-30 minutes to begin the transfusion and up to four hours to complete it.

Technique or Treatment

Here are some of the general steps providers should follow when carrying out a blood transfusion:

- Verify Blood Product

- Relay the features of a transfusion reaction to the patient. The patient should inform the nursing staff during the transfusion if these appear.

- Baseline vital signs, lung sounds, urine output, and skin color

- Prepare the Y tubing with 0.9% NaCl and have the blood unit ready in an infusion pump

- The blood should be run slowly for the first fifteen minutes, for instance, 2 ml/min or 120 ml/hr

- Staff should be supervising the patient for the first fifteen minutes as this is when most transfusion reactions happen

- The rate of transfusion can be increased after this period if the patient is stable and does not display any signs of a transfusion reaction

- Document vital signs after fifteen minutes, then every hour, and finally, at the end of the transfusion

- During the transfusion, look for any signs of transfusion reactions

- If a reaction is suspected, stop the transfusion immediately

- Disconnect the blood tubing from the patient

- Inform the provider, stay with the patient and assess the status

- Document everything

- After the transfusion, flush Y tubing with normal saline and dispose of used Y tubing in the biohazard bin

- Obtain post-transfusion vital signs

- After the procedure, some patients could experience soreness at the puncture site, but this should dissipate quickly.

Complications

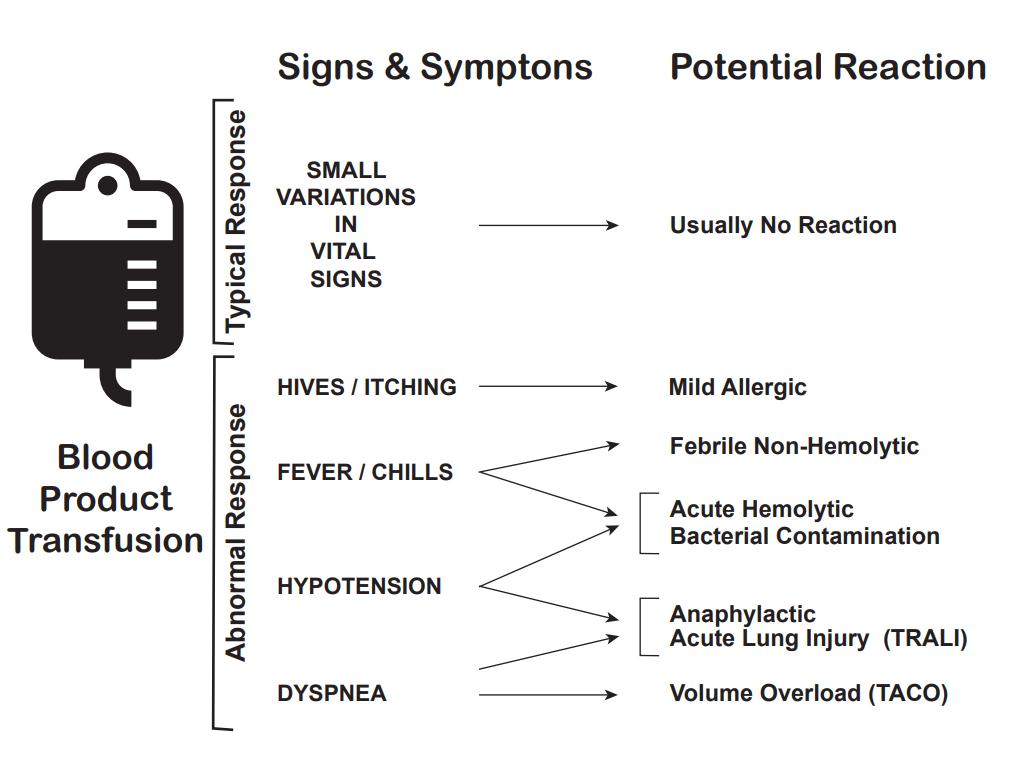

There are multiple complications of blood transfusions, including infections, hemolytic reactions, allergic reactions, transfusion-related lung injury (TRALI), transfusion-associated circulatory overload, and electrolyte imbalance.[23][24][25]

According to the American Association of Blood Banks (AABB), febrile reactions are the most common, followed by transfusion-associated circulatory overload, allergic reaction, TRALI, hepatitis C viral infection, hepatitis B viral infection, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and fatal hemolysis which is extremely rare, only occurring almost 1 in 2 million transfused units of RBC.

For comparison, the lifetime odds of dying from a lightning strike are about 1 in 161,000.

A list of approximate risk per unit transfusion of RBC (adapted from AABB clinical guidelines published JAMA November 15, 2016) will be discussed here.[6]

Adverse Event and Approximate Risk Per Unit Transfusion of RBC

- Febrile reaction: 1:60

- Transfusion-associated circulatory overload: 1:100

- Allergic reaction: 1:250

- TRALI: 1:12,000

- Hepatitis C infection: 1:1,149,000

- Human immunodeficiency virus infection: 1:1,467,000

- Fatal hemolysis: 1:1,972,000

Febrile Reactions[26]

Transfusing with leukocyte-reduced blood products, which most blood products in the United States are, may help reduce febrile reactions. If this occurs, the transfusion should be halted, and the patient evaluated, as a hemolytic reaction can initially appear similar and consider performing a hemolytic or infectious workup. The treatment is with acetaminophen and, if needed, diphenhydramine for symptomatic control. After treatment and exclusion of other causes, the transfusion can be resumed at a slower rate.

Transfusion-associated Circulatory Overload[27]

It is characterized by respiratory distress secondary to cardiogenic pulmonary edema. This reaction is most common in patients already in a fluid-overloaded state, such as congestive heart failure or acute renal failure. Diagnosis is based on symptom onset within 6 to 12 hours of receiving a transfusion, clinical evidence of fluid overload, pulmonary edema, elevated brain natriuretic peptide, and response to diuretics.

Preventive efforts and treatment include limiting the number of transfusions to the lowest amount necessary, transfusing over the slowest possible time, and administering diuretics before or between transfusions.

Allergic Reaction[28]

It often manifests as urticaria and pruritis and occurs in less than 1% of transfusions. More severe symptoms, such as bronchospasm, wheezing, and anaphylaxis, are rare. Allergic reactions may be seen in patients who are IgA deficient, as exposure to IgA in donor products can cause a severe anaphylactoid reaction. This can be avoided by washing the plasma from the cells prior to transfusion. Mild symptoms, such as pruritis and urticaria can be treated with antihistamines. More severe symptoms can be treated with bronchodilators, steroids, and epinephrine.

Transfusion-related Lung Injury (TRALI)[29]

This is uncommon, occurring in about 1:12,000 transfusions. Patients will develop symptoms within 2 to 4 hours after receiving a transfusion. Patients will develop acute hypoxemic respiratory distress, similar to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Patients will have pulmonary edema, normal CVP, without evidence of left heart failure CVP. Diagnosis is made based on a history of recent transfusion, chest x-ray with diffuse patchy infiltrates, and the exclusion of other etiologies. While there is a 10% mortality, the remaining 90% will resolve within 96 hours with supportive care only.

Infections

These are potential complications. However, the risk of infections has decreased due to the screening of potential donors, so hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus risk are less than 1 in a million.[30] Bacterial infection can also occur, but does so rarely, about once in every 250,000 units of red cells transfused.

Fatal Hemolysis

This is extremely rare, occurring only in 1 out of nearly 2 million transfusions. It results from ABO incompatibility, and the recipient’s antibodies recognize and induce hemolysis in the donor’s transfused cells. Patients will develop an acute onset of fevers and chills, low back pain, flushing, dyspnea as well as becoming tachycardic and going into shock. Treatment is to stop the transfusion, leave the IV in place, intravenous fluids with normal saline, and keep urine output greater than 100 mL/hour, diuretics may also be needed. Cardiorespiratory support may be provided as appropriate. A hemolytic workup should also be performed, including sending the donor blood and tubing and post-transfusion labs (see below for list) from the recipient to the blood bank.

- Retype and crossmatch

- Direct and indirect Coombs tests

- Complete blood count (CBC), creatinine, PT, and PTT (draw from the other arm)

- Peripheral smear

- Haptoglobin, indirect bilirubin, LDH, plasma-free hemoglobin

- Urinalysis for hemoglobin

Electrolyte Abnormalities

They can also occur, although these are rare and more likely associated with large volume transfusion.

- Hypocalcemia can result as citrate, an anticoagulant in blood products, binds with calcium.[31]

- Hyperkalemia can occur from the release of potassium from cells during storage. Higher risk in neonates and patients with renal insufficiency.[32]

- Hypokalemia can result as a result of alkalinization of the blood as citrate is converted to bicarbonate by the liver in patients with normal hepatic function.

Clinical Significance

As mentioned in the introduction, the science of transfusion medicine, including the transfusion of red blood cells, has evolved significantly over the past century. The field of transfusion medicine has evolved as well and includes representation from multiple medical specialties. The ability to transfuse red cells into patients safely and rapidly has revolutionized the care of trauma patients, surgical patients, and patients with gastrointestinal bleeding, among other conditions. Transfusion medicine will continue to evolve, and science is continuing to improve this process, as well as working on alternative methods to carry oxygen to cells, which would potentially reduce the risk of reactions and infection and ease storage.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Our understanding of blood transfusion has improved dramatically over the past three decades. Unlike before, empirical blood transfusions are no longer the norm. While blood products do have a benefit, they can also cause harm. Healthcare workers who look after patients needing a blood transfusion should consult with a hematologist if they remain unsure about the indications. Interprofessional team collaboration is crucial in managing patients undergoing blood transfusions and those having adverse reactions to transfusions. The key is to reduce the harm from unnecessary blood transfusions.