Continuing Education Activity

Brow ptosis is a common presenting complaint in aging patients; it can affect patients' quality of life because of its cosmetic impact and visual field obstruction. Brow ptosis is the descent of the eyebrow from its normal anatomical position down to a point at which its appearance is cosmetically displeasing, or visual field deficits develop as a result of excess soft tissue pushing downwards on the eyelid. An understanding of periorbital anatomy and the aging process is vital to properly care for these patients. This activity reviews the etiology, epidemiology, and pathophysiology of brow ptosis and explains the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the etiology of brow ptosis.

- Outline a thorough history/physical examination for periorbital aging.

- Explain the management options available for brow ptosis.

- Explain the importance of improving care coordination among the interprofessional team to enhance care delivery for patients with brow ptosis.

Introduction

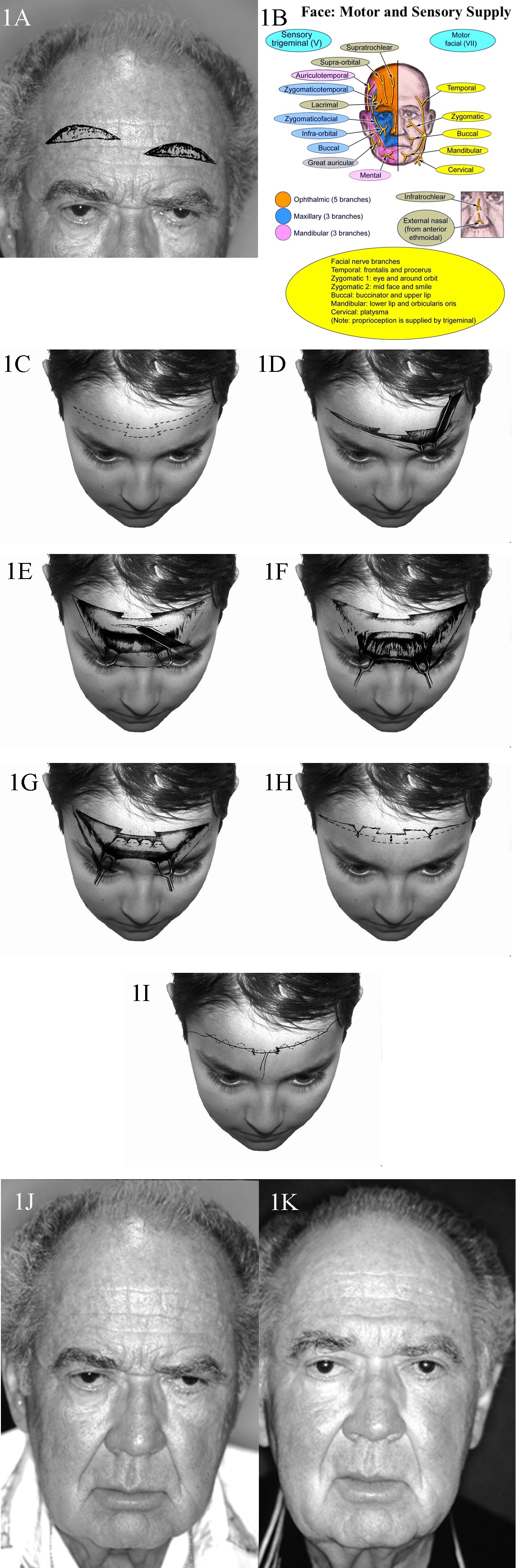

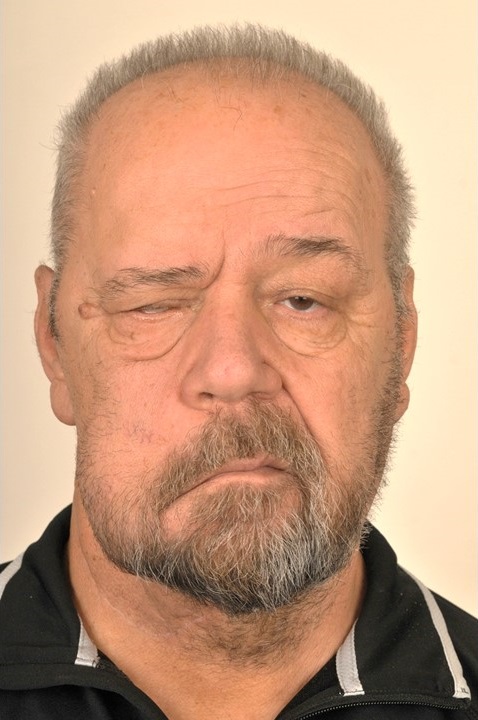

Brow ptosis is the descent of the eyebrow from its normal anatomical position down to a point at which its appearance is cosmetically displeasing, or visual field deficits develop as a result of excess soft tissue pushing downwards on the eyelid. Most commonly, this condition is seen in the elderly due to age-related involutional change of the facial soft tissues, but brow ptosis may also accompany damage to the frontal branch of the facial nerve, which in turn prevents or impairs the frontalis muscle's elevation of the brow or maintenance of appropriate brow position at rest.[1]

When the brow descends, it compresses the soft tissues of the eyelid and weighs them down, often causing excess skin to prolapse over the lid margin and contact the eyelashes, a condition known as pseudoptosis. While pseudoptosis may be mistaken for true blepharoptosis, distinguishing between them is straightforward: elevating the brow to its correct position will alleviate the issue in pseudoptosis, while the lid margin will remain low in cases of true blepharoptosis. Of course, the two problems may coexist, as the etiopathogeneses are not mutually exclusive.

Etiology

Brow ptosis is almost always acquired. Congenital brow ptosis is rare and occurs when there is an underdevelopment of the facial nerve and/or the mimetic muscles.

Cases of acquired brow ptosis may arise in a variety of ways:

- Age-related: This is the most common form and is associated with changes in the soft tissues of the brow. Increased laxity of the connective tissue, skin, and frontalis muscle initially leads to drooping in the lateral third of the eyebrow and may progress to ptosis of the medial two-thirds if left untreated.[2] (see image)

- Traumatic: Damage to the intracranial, intratemporal, or extratemporal facial nerve can result in ptosis of the brow. A hemifacial palsy will result if the damage is anywhere between the facial nerve nucleus proximally and the pes anserinus distally. Damage specific to the frontal branch will denervate the ipsilateral frontalis muscle and parts of the corrugator supercilii, procerus, and orbicularis oculi muscles.[3] Fracture of the temporal bone is one of the most common traumatic causes of traumatic facial palsy. Other causes include trauma to the parotid gland, zygomatic arch, and mandibular body.

- Myogenic: Myopathy specific to the facial musculature and systemic myopathy can contribute to brow ptosis via atrophy or denervation of the frontalis muscle. Examples of these conditions include myasthenia gravis, myotonic dystrophy, and oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy.[4]

- Infectious: Ramsay Hunt syndrome is a reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus that leads to facial paralysis and a herpetic rash of the ear canal, auricle, scalp, or oropharyngeal mucous membranes. This condition causes an ipsilateral facial palsy that includes brow ptosis.[5] Many other infectious agents can lead to central or peripheral facial nerve dysfunction, including but not limited to herpes simplex virus, Lyme disease, tertiary syphilis, West Nile virus, HIV, SARS-CoV-2, polio, and COVID.[6][7]

- Spasm-induced: Congenital or acquired spasms of the orbicularis oculi can pull the brow down and away from its anatomic position, eventually causing a permanent change. Examples include blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm.[8] (see video)

- Neoplastic: Neoplasms of, or infiltrating into, the facial nerve affect its function and cause brow ptosis. Some of the most common include cancer of the overlying skin, like melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma, or more proximal masses, like acoustic neuromas.

- Iatrogenic: Operations in the area of the brow pose a significant risk to the innervation and structural integrity of the brow. Overall, the procedures that pose the highest risk for postoperative facial nerve palsy are temporal artery biopsy, acoustic neuroma resection, and temporomandibular joint procedures. Operations to improve brow and overall facial cosmesis, such as endoscopic and open facelift procedures, can cause facial nerve palsy and exacerbate the problem they attempted to correct, but this occurs in less than 1% of procedures. Botulinum toxin injection also carries a risk of brow ptosis; overzealous or misplaced injections effectively denervate the brow elevators.[9]

Epidemiology

Anecdotally, it would appear that the bulk of cases are associated with the natural aging process, although literature definitively investigating the epidemiology of brow ptosis is lacking. Congenital brow ptosis is rare, as only 4.9% of facial palsy cases are present at birth.[6] The small proportion of remaining cases is attributable to the other acquired etiologies discussed above.

Pathophysiology

Several soft tissue layers comprise the brow. From superficial to deep, they include the skin, the subcutaneous fat, and the frontalis muscle; deep to this; there are the periosteum and skull.[10] The frontalis muscle is the sole elevator of the brow.[11] The depressors of the eyebrow include the orbicularis oculi, procerus, and depressor supercilii muscles (the latter some surgeons consider to be simply a portion of the orbicularis oculi muscle).[12] The facial nerve innervates all muscles of facial expression; its frontal branch innervates the frontalis and the lateral portions of the orbicularis oculi and corrugator supercilii, while the zygomatic branch innervates the procerus, the medial aspects of the corrugator supercilii and orbicularis oculi, and the depressor supercilii.[13]

Sun exposure, gravity, and the natural involutional degeneration of the skin and soft tissues are the main contributors to brow ptosis. Denervation of the brow elevators, whether via trauma, surgery, botulinum toxin treatment, or disease process, will also lead to brow ptosis. Long-term spasm of the brow depressors can also lead to brow ptosis. Spasms may result from spastic dystonia after facial denervation, facial tics in conditions like Tourette syndrome, or spastic syndromes like blepharospasm.

History and Physical

The historical evaluation of a brow ptosis patient is key to determining the underlying etiology.

- The history of the present illness should be focused on the onset and progression of symptoms. A slowly progressive onset in an older patient may indicate an age-related cause. In contrast, patients with more rapid onset may be suffering from Bell palsy, trauma, neoplasm, or other more unusual causes. A waxing and waning course with accompanying fatigability could represent myotonic dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, or oculopharyngeal dystrophy.

- The medical history should specifically evaluate for past instances of facial paralysis of any etiology, even cases long in the past.

- History of chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy should be determined, as these exposures can speed cutaneous and soft tissue aging.

- The surgical history should reveal all procedures performed in the area of the brow and along the course of the facial nerve, including any neuro-otologic or neurosurgical procedures. Patients should be asked if they have received chemodenervation with botulinum toxin injections as well.

- The social history should reveal sun exposure, smoking, and drug use, as they can all expedite involutional changes.

The physical examination should follow a formulaic, stepwise approach that is generalizable to all periorbital aging.[10]

- Neutral brow position should be evaluated by having the patient close their eyes, relax the facial muscles, and open the eyes as gently as possible without raising the brows.

- Brow versus lid pathology should be differentiated via manual elevation of the brow to the neutral position. A lid that is still ptotic after brow elevation indicates true blepharoptosis rather than pseudoptosis caused by a drooping brow.

- Blepharoptosis should be thoroughly evaluated. The margin-reflex distance (MRD) is recorded. This is the distance measured from the corneal light reflex to the upper lid margin (MRD-1) or lower lid margin (MRD-2). MRD-1 less than 2-3 mm is indicative of blepharoptosis. The distance must also be measured between the upper eyelid margin and the superior palpebral crease. More than 8 to 10 mm often indicates blepharoptosis due to levator aponeurosis dehiscence. Brow asymmetry must also be noted if present. An asymmetric brow with symmetric eyelids may mask ptosis on the side of the elevated brow due to frontalis contraction compensating for a ptotic eyelid. The ice pack test may also be employed at the bedside if myasthenia gravis is suspected; placing an ice pack on the patient's eyelids (with a barrier to prevent frostbite) for 2 to 5 minutes will often improve blepharoptosis in patients with myasthenia gravis.[14] Finally, the patient must be evaluated for the Hering phenomenon. If the elevation of a ptotic lid - or the lid on the side of the elevated brow - produces drooping of the contralateral upper eyelid, the patient may have bilateral but asymmetric blepharoptosis. Brow height asymmetry is also commonly caused by hemifacial microsomia, more frequently on the right than on the left.

- While not directly applicable to the evaluation of brow ptosis, the points mentioned here are essential to a thorough periorbital examination: festoons and fat pseudoherniation should be evaluated with digital pressure on the globe while visualizing the upper and lower lids. The former will not enlarge, but the latter will. Festoons will also contract with effortful eye closure. Lower lid laxity should be evaluated via the snap test. This is performed by distracting the lid from the globe, then releasing and observing lid recoil, which should take no longer than 2 seconds and should occur without the patient needing to blink. The lower eyelid vector should be evaluated by observing the relationship between the cornea and the cheek with the patient's head in the Frankfort horizontal position. The vector is negative if the cornea is anterior to the cheek skin at the infraorbital rim. This is associated with aging and an increased risk of ectropion if lower lid blepharoplasty is performed. Finally, tear production should be evaluated via the Schirmer test. Filter paper is inserted into the fornix of the lower eyelid; if there is less than 10 mm of dampness after 5 minutes, tear production is not adequate, and the surgeon must adjust the operative plan accordingly.

- The hairline position and shape of the forehead must be visually evaluated to inform the surgeon's choice of operative approach.

- A thorough cranial nerve exam should be carried out, especially if damage to the facial nerve is suspected.

Evaluation

Evaluation of brow ptosis outside of a thorough history and physical examination is rarely necessary. However, there are some cases in which imaging and laboratory studies are beneficial or even diagnostic. Myogenic causes of brow ptosis may be elucidated with certain assays; for example, myasthenia gravis may be diagnosed via serologic testing for acetylcholine receptor antibodies.[15] Brow ptosis caused by neoplasm will necessitate a thorough evaluation of the mass. These assessments vary widely based on the suspected type of neoplasm, including anything from shave biopsy to magnetic resonance or positron emission tomography scanning.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of brow ptosis is dependent on brow morphology, ptosis etiology, severity, and, most importantly, patient goals.[16] For age-related brow ptosis, surgical management will be most effective. Surgery may also be indicated in some traumatic, neoplastic, and iatrogenic causes. Those surgeries may include nerve decompression, removal of a neoplasm, or nerve reconstruction and are outside the scope of the current discussion. More common procedures used to treat brow ptosis are discussed below. Many of these procedures are combined with other rejuvenation procedures, such as upper blepharoplasty, botulinum toxin injection, or skin resurfacing, to optimize patient outcomes.

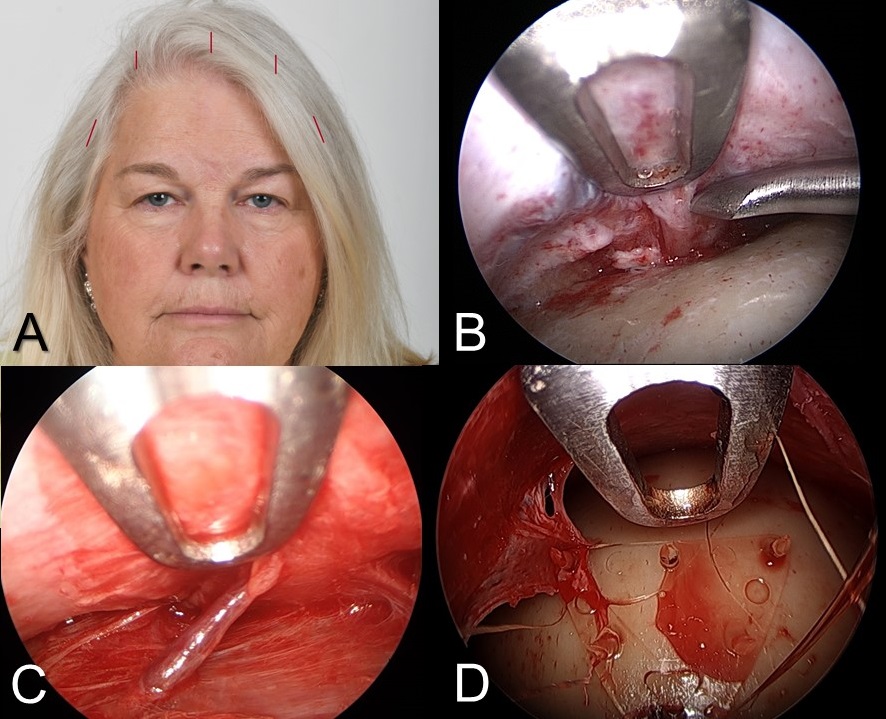

The endoscopic brow lift also called the "endobrow" procedure, is the most commonly employed approach to brow lifting (see image).[17] Dissection is performed via a median and two paramedian incisions in the subperiosteal plane and via two temporal incisions in a plane between the fascia of the temporalis muscle and the temporoparietal fascia to release the periosteum around the superior and lateral orbit at the arcus marginalis. The procedure typically involves visualizing and preserving the supraorbital neurovascular bundles as well as the medial zygomaticotemporal veins, known as the "sentinel veins," which are located within approximately 10 mm of the frontal branches of the facial nerve and serve to warn the surgeon of their proximity.[18] Then the periosteum is lifted and fixated to the skull; this is often accomplished with resorbable implants but may also be performed with screws and staples or a drill and suture.[19]

The endoscopic brow lift is best suited for patients with low or average brow height, defined as six or fewer centimeters from the brow to the hairline, and those without significant curvature or bossing of the forehead. A significant benefit of this procedure is that it can address glabellar rhytides, a common comorbidity of brow ptosis, through the division of the corrugator supercilii and/or procerus muscles. Some limitations include the risk of damage to the frontal branch of the facial nerve (which would exacerbate brow ptosis), risk of damage to the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves (which would cause forehead numbness), difficulty in correcting brow asymmetry, and limited ability to achieve a dramatic elevation. The most significant limitation on the degree of lift achieved with the endobrow procedure is downward traction from the closure of concomitantly performed upper eyelid blepharoplasty.[20]

Open coronal approaches constitute a more traditional category of options. Pretrichial incisions are placed at or just in front of the hairline, while trichophytic incisions are hidden within the hairline; the classic coronal incision passes directly over the vertex of the scalp. Dissection is carried forward in the subgaleal plane until diving subperiosteally 1 to 2 cm superior to the orbital rim. The flap is elevated, the excess skin and soft tissue are excised as necessary, and the incision is closed (see image). As with the endoscopic brow lift, division of the arcus marginalis is important, and avoiding injury to the supraorbital neurovascular bundles is critical. While most supraorbital bundles exit the skull through notches, roughly 25% will exit via foramina, which obstruct access to the orbital rim and often require osteotomies for complete forehead flap mobilization; performing these osteotomies to convert foramina into notches may place the supraorbital nerves at increased risk of injury. Coronal brow lifts allow for more dramatic lifts than the endoscopic option provides, and they do not require expensive endoscopic equipment; however, they result in significant scars that may be revealed by hair loss and more commonly cause minor complications like forehead numbness, pruritus, and alopecia, as well as long-term anesthesia or hypesthesia posterior to the incision in nearly all patients.[21] The pretrichial coronal approach is also commonly used for facial feminization procedures, in which the brow lifting operation is accompanied by an adjustment of the frontal hairline and a reduction of the supraorbital ridge.[22]

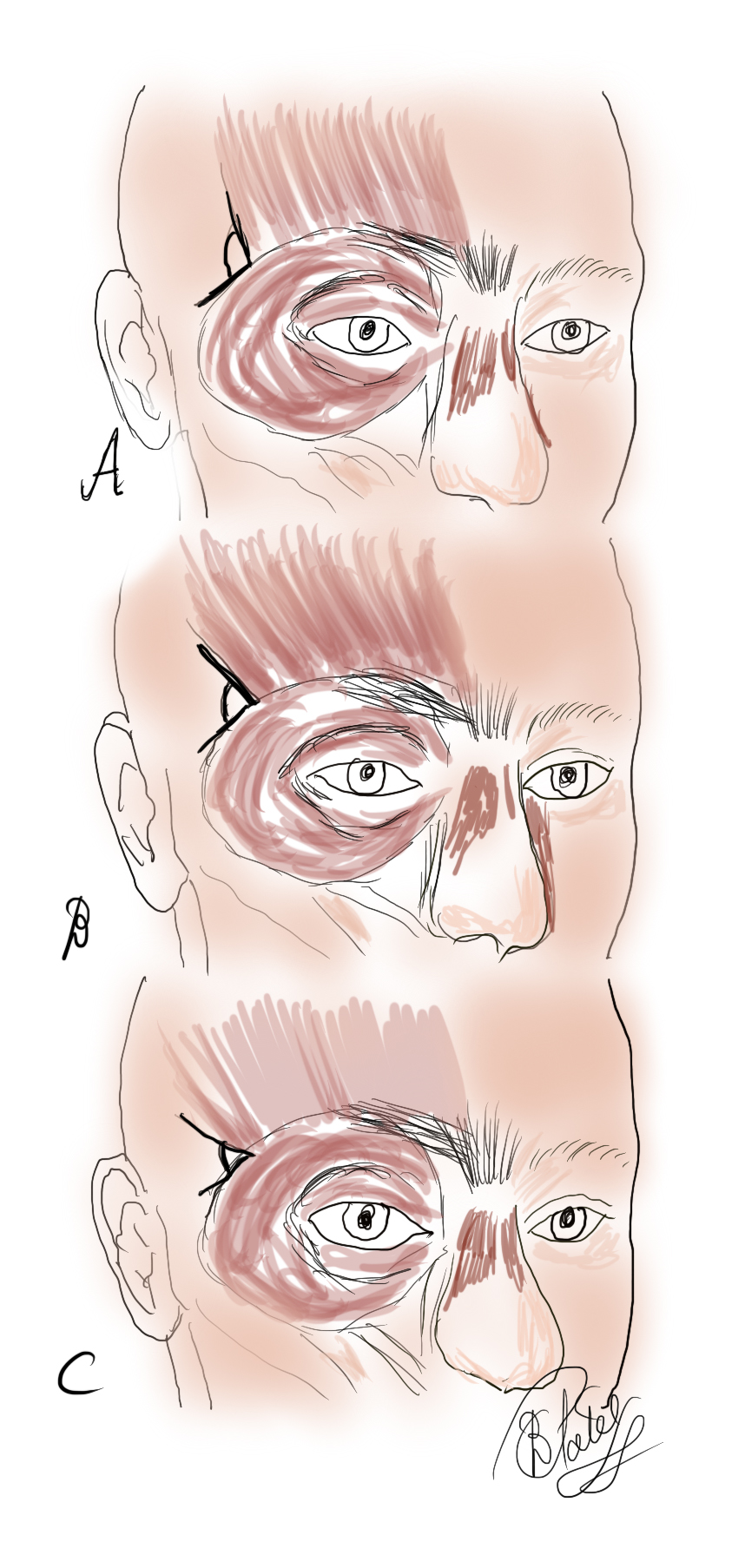

The direct brow lift is performed through an incision just above the hair-bearing brows. Excess skin and soft tissue are excised to create a considerable lift with a relatively minor procedure that can easily be performed in the clinic under local anesthesia (see image). This procedure is the most effective option for heavy lateral hooding and is the most straightforward procedure with which to correct brow asymmetry. Its drawbacks include the risk of visible scarring - particularly over the medial brow, where the skin is more sebaceous - and an increased chance of excessive elevation that may result in a surprised look, but because this technique addresses each brow separately, it is ideally suited for alleviating most cases of brow asymmetry.[23]

For severe brow asymmetry, particularly for patients with facial paralysis and very heavy soft tissues, unilateral suture suspension of the ptotic brow to a titanium miniplate fixated to the frontal bone at the level of the hairline may be effective. As a side benefit, the sutures can potentially be tightened under local anesthesia in the future if the brow ptosis recurs or worsens.

The transblepharoplasty browpexy is a way to combine the treatment of upper lid dermatochalasis or blepharoptosis with the treatment of brow ptosis. These conditions are often comorbid, so this approach is becoming more common. An upper eyelid blepharoplasty is performed first; then, dissection is carried superiorly along the orbital septum until the pericranium above the supraorbital rim is reached. This periosteum can be used as an anchor to suspend the brow using either a suture or an absorbable implantable device. Similar to the results of the endoscopic approach, the results obtained with this procedure are limited.

The mid-forehead brow lift is mostly a procedure of historical interest, in which an incision is hidden within a deep, transverse forehead rhytid (see image). The excess skin and soft tissue are excised, and the incision is closed similarly to the direct brow lift. It has been largely abandoned because the scars it produces are challenging to hide, and other options allow for a similar amount of lift.[24]

Nonsurgical treatment may be pursued in particular cases. Botulinum toxin injections effectively treat spastic brow ptosis or even slightly elevate the brow by weakening the depressor supercilii muscle; more systemic etiologies like myasthenia gravis will require specialized medical therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

Brow ptosis is a fairly straightforward and well-defined diagnosis but may be confused with or obscured by other periorbital pathology. Asymmetric brow ptosis may seem like unilateral pathology unless a thorough physical examination reveals that the more ptotic side was masking the appearance of the less ptotic side. Severe dermatochalasis or blepharoptosis may distract the physician from identifying concomitant brow ptosis. A thorough history and physical examination will reveal whether a patient’s brow ptosis is age-related, traumatic, myogenic, spasm-induced, infectious, neoplastic, or iatrogenic.

Prognosis

Prognosis is highly dependent on etiology and the patient's primary concerns. For those mainly focused on the visual field deficits caused by their ptotic brows, full resolution and patient satisfaction can usually be achieved.[25] Patients whose concerns are primarily cosmetic have higher dissatisfaction rates. Patients with non-age-related etiologies have more varied prognoses.

Complications

Brow ptosis itself rarely progresses to more serious pathology. Its most clinically significant sequela is visual field obstruction, progressing from lateral to medial. Brow ptosis correction surgery complications include patient dissatisfaction (7.4%), numbness of the forehead due to supratrochlear and supraorbital nerve damage (5.5%), alopecia (2.8%), and brow asymmetry (1.7%). Nonsurgical brow rejuvenation complications are very rare. The most common complication of botulinum toxin treatment is periorbital bruising in 1.7% of patients.[9]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated to their desired level of detail on the pathophysiology of the cause of brow ptosis. Once a sufficient understanding of the pathology is achieved, surgical and non-surgical treatment options should be explained to inform a decision. A thorough discussion of common and rare complications of the chosen treatment method is essential before undertaking an operative intervention.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Brow ptosis is a relatively common problem but is often misdiagnosed or overlooked due to more apparent upper eyelid pathologies. When patients present to primary care providers, they should be referred to a facial plastic, general plastic, or oculoplastic surgeon for definitive treatment. Once patients are directed to the correct surgeon, close coordination among nurses, physicians, case managers, and others in direct contact with the patients is key to timely and satisfactory outcomes. Cases that are not age-related may require further consultation with neurosurgeons, infectious disease specialists, neurologists, rheumatologists, or other specialists.

Intraoperatively, an interprofessional support staff of specialty-trained nurses who are familiar with the equipment and selected procedure in cooperation with a properly trained and experienced surgeon is crucial to executing a safe and effective procedure that produces satisfactory outcomes. [Level 5]