Continuing Education Activity

Cachexia is a complicated metabolic syndrome related to underlying illness and characterized by muscle mass loss with or without fat mass loss that is often associated with anorexia, an inflammatory process, insulin resistance, and increased protein turnover. This activity reviews the pathophysiology of cachexia and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of cachexia.

- Review the history and physical exam features of a patient with cachexia.

- Summarize the treatment options for cachexia.

- Explore modalities to improve care coordination among interprofessional team members in order to improve outcomes for patients affected by cachexia.

Introduction

Cachexia is a complicated metabolic syndrome related to underlying illness and characterized by muscle mass loss with or without fat mass loss that is often associated with anorexia, an inflammatory process, insulin resistance, and increased protein turnover.[1][2][3][4][5]

Etiology

Cachexia causes weight loss and increased mortality. The major cause is cytokine excess. Other mediators include testosterone and insulin-like growth factor-I deficiency, excess myostatin, and excess glucocorticoids.

Epidemiology

In cancer patients, the overall prevalence of cachexia ranges from 40% at cancer diagnosis to 70% in advanced disease. In 20% to 25% of patients with advanced solid tumors, it is considered the primary cause of death in addition to being a significant comorbidity reducing median survival by up to 30%. Although less well delineated, cachexia is also associated with other chronic diseases including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and chronic infectious and inflammatory diseases including AIDS. Significantly shorter survival in advanced cancer patients with cachexia has been identified relative to those without cachexia.[6][7][8][9]

Pathophysiology

Cachexia is characterized by a persistent increase in basal metabolic rate that is not compensated by increased caloric/protein intake. Factors involved in this abnormal metabolic cascade include digestive factors, tumor factors and hormonal responses to the primary disease. Digestive factors resulting in poor intake include dysgeusia, nausea, dysphagia, mucositis, and constipation. Tumor-mediated factors have been identified that activate proteolysis and lipolysis. Inflammatory mediators such as cytokines which include tumor necrosis factor and the interleukins induce anorexia while increasing glucagon, cortisol, and catecholamines producing a catabolic, hypermetabolic state. Hormonal anabolic mediators such as growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), testosterone, and ghrelin are reduced. In heart failure, angiotensin-II causes muscle wasting likely through the ubiquitin-proteasome system, resulting in myocyte apoptosis and significant reduction of protein synthesis. Asthenia results in part from subsequent decreases in size and number of type 1 and type 2 muscle fibers and also reduced skeletal blood flow.

History and Physical

History frequently includes a report of significant weight loss associated with the lack of appetite. Also, there is a reduction of quality of life associated with increased fatigue and poor tolerance to activity. In advanced cancer patients, cachexia is correlated with increased severity of multiple symptoms. These include lack of appetite, dry mouth, vomiting, dysgeusia, early satiety, and diarrhea. It also increases the severity of less intuitive symptoms such as pain, fatigue, and loss of energy, sleep disturbances, and anxiety. This excess symptom burden is independent of age, tumor stage, and treatment type. Diagnostic criteria for cachexia are a 5% weight loss in 12 months or a body mass index of less than 20 kg/m2 in the presence of a known chronic disease with at least 3 of the following factors:

- Loss of muscle mass,

- Asthenia

- Loss of body fat, in the presence of inflammation as evidenced by albumen less than 3.2 g/dL or increased C–reactive protein.

The physical exam is nonspecific. Exam findings may be normal early in the course of the disease. Other findings might include bitemporal muscle wasting, supraclavicular wasting, and general lack of muscle definition.

Evaluation

Supporting laboratory evidence includes albumen less than 3.2 g/lL, a pre-albumin value of less than 10 mg/dL, a transferrin level less than 100 mg/dL, and an elevated C–reactive protein.

Treatment / Management

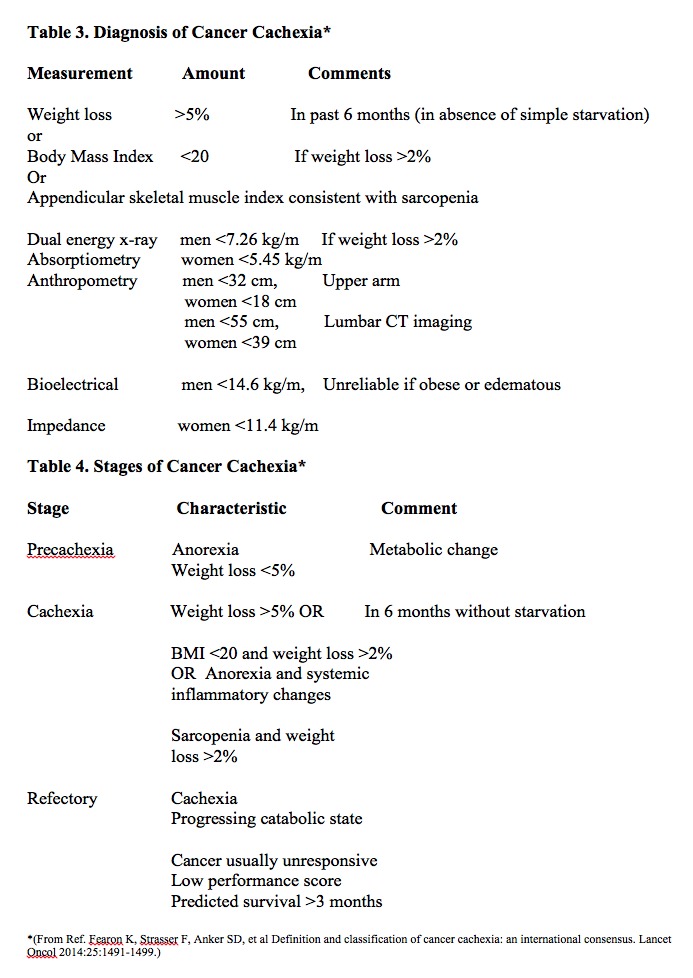

[10]Disease stages have been described as pre-cachexia, cachexia, and refractory cachexia. Consensus definitions for these stages are as follows:

- Pre-cachexia, when weight loss more than 1kg but less than 5%

- Cachexia, when weight loss is more than 5% or when weight loss is more than 2% with BMI less than 20kg/m

- Refractory cachexia, when weight loss is more than 15% with body mass index (BMI) less than 23kg/m or when weight loss is more than 20% with BMI less than 27 kg/m

Although the prognostic usefulness of these definitions has not been established, it would appear that addressing cachexia at an earlier stage might ameliorate the destructive effects of the primary condition.[1][10][11]

A multimodal approach aimed at improving appetite, reducing the inflammatory response, improving outcomes and quality of life is the focus of ongoing research. Currently, no proven therapy accomplishes all of these goals. Most of the research has focused on improving appetite. Adequate nutrition remains an important aspect of this multimodal approach. However, increasing calorie–protein intake by definition does not reverse this abnormal metabolic state. Reversing the metabolic derangement through attenuation of tumor-related.

Factors and inflammatory mediators remain of central importance. Studies indicate that interleukin-6 has a primary role in initiating inflammatory cascade along with the contribution of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and other cytokines. Interventions that are used or that are under current investigation may be useful theoretically due to their effects on this inflammatory cascade, abnormal hormone responses, and/or the hypermetabolic derangements seen in cachexia.

Physical activity may attenuate the effects of cachexia by altering muscle metabolism through increased protein synthesis and reduced degradation pathways. In addition, exercise may increase insulin sensitivity, reduce oxidative stress, and reduce response to inflammation. Both aerobic exercise and resistance exercise have proven beneficial. Resistance exercise supplemented with branched-chain amino acids can reduce sarcopenia and cachexia.

The most studied and effective treatment for anorexia has been megestrol acetate and a dose of 320 mg to 800 mg per day. The literature supports that 30% of patients demonstrate an increased appetite associated with an increased body mass index primarily through increased fat and some associated improvement in the quality of life. However, no study has demonstrated improved survival. Side effects include adrenal suppression and increase the incidence of DVT in a minority of patients. Corticosteroid has been shown to have a positive effect on appetite but, due to side effect profile, is only indicated for short-term (less than 4 weeks) treatment. In addition to appetite stimulation, steroids theoretically may reduce the inflammatory state.

Other medications that require additional confirmation includes cannabinoids (only effective in AIDS so far), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and omega-3 fatty acids. Existing evidence suggests it is reasonable to initiate a trial of omega-3 fatty acids in patients with life expectancies longer than 8 weeks. Other medications including Ghrelin, beta-2 agonists, selective androgen receptor modulators, aliskiren, resveratrol, leucine, and thalidomide are all under active investigation with some positive early trends.

In patients with cardiac cachexia, treatment with the beta-blocker carvedilol has demonstrated meaningful reversal of cachexia. This may be in part due to improvement in the hypermetabolic state seen in cachexia. Pre-clinical studies suggest that ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers have muscle-protective properties related to mitochondrial function, insulin sensitivity, and local inflammation.

Differential Diagnosis

Pearls and Other Issues

Cachexia is a syndrome of altered metabolic activity resulting in muscle protein loss that is present in up to two-thirds of patients with advanced cancer. It is estimated that 20% of patients with solid cancers die directly as a result of cachexia. Also, survival decreases to 30% in patients with this associated major comorbidity. This syndrome remains poorly recognized, treated and prevented. The current appetite stimulants have been effective in increasing weight 30% of patients, but improved survival in patients with cachexia has not been demonstrated. Clinical research directed at reducing the inflammatory state and tumor-related factors have shown some promise.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A multimodal approach aimed at improving appetite, reducing the inflammatory response, improving outcomes and quality of life is the focus of ongoing research. The management of cachexia requires an interprofessional team that includes an oncologist, gastroenterologist, dietitian, primary provider, nurse practitioner and a surgeon. Currently, no proven therapy accomplishes all of these goals. Most of the research has focused on improving appetite. Adequate nutrition remains an important aspect of this multimodal approach. However, increasing calorie–protein intake by definition does not reverse this abnormal metabolic state. Reversing the metabolic derangement through attenuation of tumor-related.

Physical activity may attenuate the effects of cachexia by altering muscle metabolism through increased protein synthesis and reduced degradation pathways. In addition, exercise may increase insulin sensitivity, reduce oxidative stress, and reduce response to inflammation. Both aerobic exercise and resistance exercise have proven beneficial. Resistance exercise supplemented with branched-chain amino acids can reduce sarcopenia and cachexia.

Even though a number of drugs have been used to manage cachexia, none works reliably or consistently. The outcomes for most patients depends on the cause. Those with malignancy tend to have the worst outcomes.[12][13] (Level V)