Continuing Education Activity

Cardiac trauma, a critical condition resulting from either blunt or penetrating injuries, presents a spectrum of outcomes from minor, self-resolving arrhythmias to fatal injuries. Rapid fatality is common, with approximately 90% of individuals with lethal cardiac trauma dying before reaching the hospital. Survival rates for those who do reach medical facilities range from 20% to 75%. The evaluation, management, and treatment of cardiac trauma involve a systematic approach guided by Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocols.

Blunt and penetrating cardiac injuries require different diagnostic strategies, ranging from electrocardiograms and cardiac-specific troponins to echocardiography and point-of-care ultrasound. In stable patients, computed tomography and transesophageal echocardiography offer detailed imaging to guide treatment decisions. Management of cardiac trauma varies depending on the injury. Dysrhythmias may require advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS) and potential electrical cardioversion; myocardial contusions are treated supportively; and cardiac ruptures necessitate surgical intervention. Penetrating injuries generally require operative management, with techniques to control bleeding and repair lacerations being crucial. Interprofessional teamwork is vital in managing cardiac trauma, ensuring comprehensive care from initial assessment through to definitive treatment. Despite advancements in medical care, the survival rate for traumatic cardiac arrest remains low, highlighting the need for rapid, coordinated intervention to improve outcomes. This activity for healthcare professionals is designed to enhance the learner's competence in performing the recommended evaluation of patients with cardiac trauma and implementing an appropriate interprofessional approach when managing this condition.

Objectives:

Identify common mechanisms of injury associated with cardiac trauma.

Evaluate a patient with cardiac trauma.

Implement the appropriate management for each type of cardiac trauma.

Apply interprofessional team strategies to improve care coordination and outcomes of patients with cardiac trauma.

Introduction

Trauma continues to be a leading cause of death and disability across all age groups, with a particularly significant impact on children and young adults under the age of 44.[1] Cardiac trauma can be classified as either blunt or penetrating injuries, with outcomes ranging from lethal injuries to spontaneously resolving arrhythmias. Despite advancements in modern medical care over the past few decades, the survival rate for traumatic cardiac arrest (TCA) remains very low, typically ranging from 3.3% to 9.2%.[2] Patients with lethal injuries often deteriorate quickly, with some studies reporting >90% of individuals expiring before arriving at a hospital and a survival rate of only 20% to 75% of those who are still alive upon arrival to the hospital.[3]

Etiology

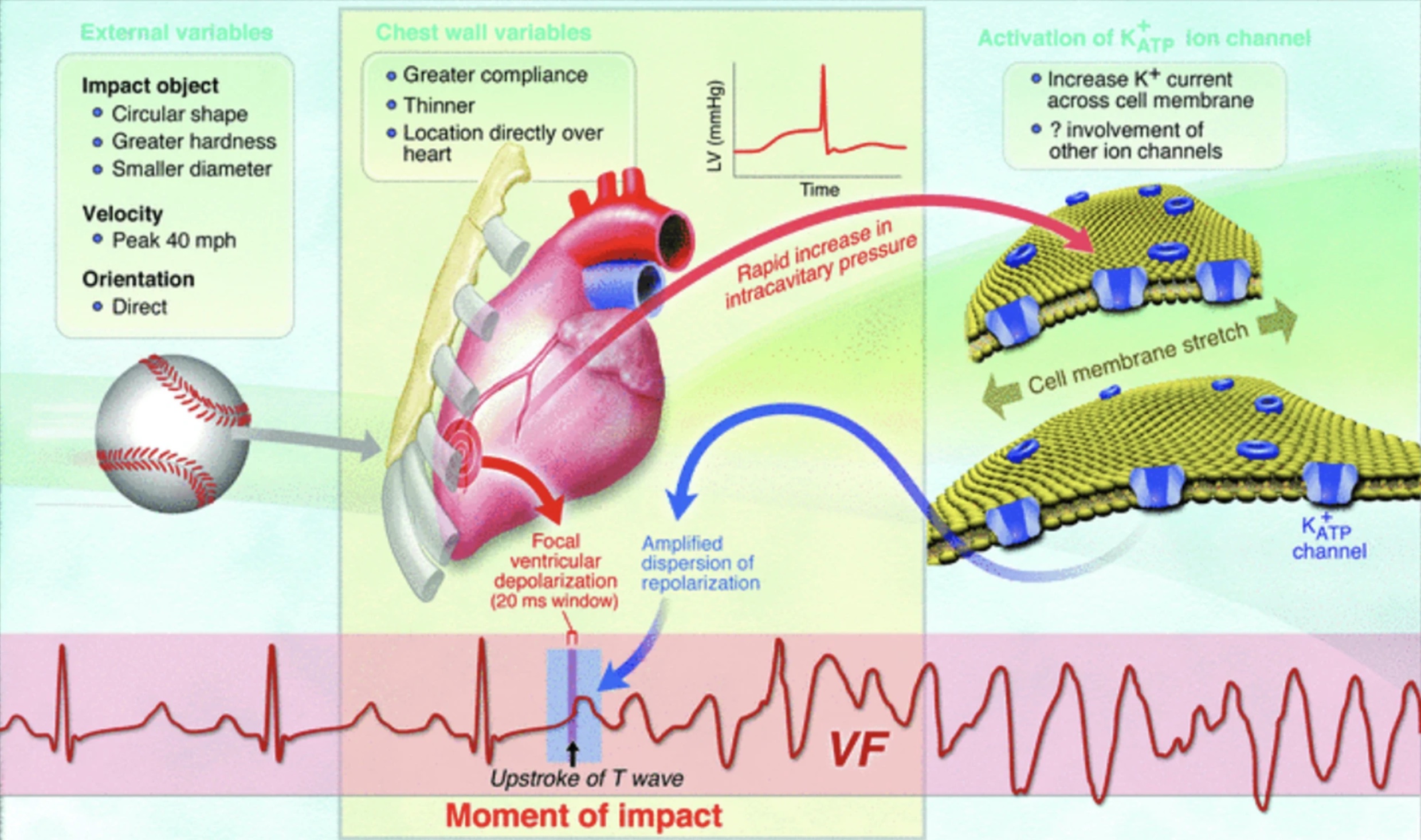

Since the nationally televised cardiac arrest of NFL player Damar Hamlin in January 2023, commotio cordis has garnered significant public attention. This condition is defined as sudden cardiac arrest caused by a direct blow to the chest, leading to ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia (Image. Commotio Cordis).[2] A direct impact on the anterior chest, sudden high-speed deceleration, compression of the chest, or a mixture of those generally cause blunt cardiac trauma. Motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause and include all 3 mechanisms above. Individuals struck by motor vehicle falls, crush injuries, and seemingly innocuous trauma such as sports-related (baseball hitting a chest) or animal-related (animal kick) may also cause blunt cardiac injury (BCI).[4]

Penetrating cardiac trauma (PCT) is among the most fatal types of chest trauma, with mortality rates ranging from approximately 16% to 43%, even at top-level quaternary care centers.[5] The primary causes of death following PCT include bleeding, cardiac tamponade, and cardiac failure, with cardiac tamponade offering an early yet critical window for potential survival. Prompt management is essential for patients with PCT, with the definitive treatment involving the surgical drainage of pericardial blood and repair of the underlying cardiac injury.

Epidemiology

BCI may affect anyone, but most often affects males with an average age in the 30s. Pediatric patients with blunt cardiac injury are also usually male, with a mean age of 7, and most commonly from motor vehicle accidents. Patients with blunt thoracic trauma have been estimated to have an incidence of electrical abnormalities as high as 30%. Research based on animal models and initial electrocardiogram (ECG) data recorded in the field or the emergency department indicates that ventricular fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia are the most prevalent arrhythmias.[6]

Any gender or aged individual may be the victim of a penetrating cardiac injury. However, penetrating cardiac trauma most commonly occurs in males and individuals in the 3rd or 4th decade of life. The right ventricle is the area most frequently injured, followed by the left ventricle. Atrial or multiple-chamber injuries are the least common.[7]

Pathophysiology

Cardiac contusion following blunt chest trauma can result in myocardial necrosis, which may ultimately cause cardiac rupture and even sudden cardiac death.[8] Anterior thoracic blunt trauma can result in bruising secondary to a decelerating force. This sudden decelerating force leads to the heart's abrupt compression to the sternum's dorsal side, called a coup. The thoracic spine can contribute an additive traumatic force to the total energy the rib cage absorbs by hitting the heart at the posterior side, called contrecoup. The distance between the sternum and spine subsequently decreases, resulting in septal or intracardiac component injuries.[9][10]

Histopathology

Defects in mitochondrial function and structure are significantly prominent in the pathogenesis of multiple myocardial injuries.[11] Multifocal subepithelial contusions of ventricles might be evident. Several experimental studies have investigated morphological changes in the myocardium following cardiac concussion.[12] The heart's gap junction profile is crucial for ion homeostasis, the development of arrhythmias, and contractile function. Changes in connexin 43 have been linked to both ischemic and nonischemic cardiac injuries.[13] Blunt trauma may cause myocardial infarction associated with time-sensitive histopathological changes. In the first few minutes following a myocardial infarction, the increased distance of the cross stripe in the infarcted zone is notable.[12] Within the first 30 minutes, swelling of the mitochondria is significant. Myocyte edema, glycogen loss, and decreased myoglobin stainability in the immunohistochemistry staining are predictable in the following 30 minutes. Hyalinised myocytes are visible for 2 to 3 hours following the myocardial infarct. However, the first agglutinated sarcoplasmic tubes are typically noted after 3 to 4 hours. Primary evidence of necrosis and extended necrosis zone is visible in the first 4 to 7 hours and after 18 hours postinfarction.[14][15]

History and Physical

The history of events for patients with a cardiac injury is often straightforward, detailing some mechanism injuring the chest or back. However, some individuals may give conflicting clinical histories due to potential legal ramifications or altered mentation. A subset of patients may also be unconscious or without a pulse, with information only available from first responders.

The physical examination of a patient with potential cardiac trauma should typically follow the primary and secondary survey of Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS). A brief evaluation of circulation and the cardiac system should occur, obtaining initial vital signs and ensuring the airway and breathing are intact and not compromised. Inspection for apparent anterior and lateral chest wounds, auscultation for muffled heart tones, murmurs, and arrhythmias, and palpation for strength and presence of pulses should be performed. After completing a primary survey, a secondary survey with further examination for a potential cardiac injury should be performed, including evaluating for distended neck veins and evaluating for signs of trauma to the posterior and lateral torso. While a patient may have stable vital signs and few features to suspect a cardiac injury, findings concerning cardiac trauma include hypotension, tachycardia, arrhythmias, visible trauma, distended neck veins, muffled heart sounds, and other signs of shock.[16]

Evaluation

Evaluating patients with concern for cardiac trauma following physical examination is multifaceted and varies depending on the nature of the mechanism of injury. A general trauma evaluation is typically performed, including chest x-rays and a point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS).[17] Chest x-rays have limited utility for diagnosing BCI but may assist with penetrating cardiac traumas by demonstrating the presence and approximate location of a foreign body, hemothorax, displaced heart, and other noncardiac thoracic injuries. Acute cardiac tamponade is unlikely to show significant findings on an initial radiograph.

POCUS is commonly utilized in emergency departments, with a focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) imaging routinely performed in patients with traumatic injuries. The FAST examination includes a cardiac view, which can aid in rapidly diagnosing pericardial effusions. The traditional FAST protocol involves examining 4 regions: the pericardium to identify cardiac tamponade, the right upper abdominal quadrant, the left upper abdominal quadrant, and the pelvis to detect hemoperitoneum. The extended FAST protocol additionally checks the pleural spaces for hemothorax and pneumothorax.[18]

While physical examination findings (eg, distended neck veins and abnormal vital signs), can be used with POCUS to demonstrate tamponade, the findings of inferior vena cava distension and septal bounce can also be identified on POCUS. Other findings, including wall motion and valvular abnormalities, may be identified for individuals more proficient with POCUS or through ordering a formal echocardiography study. If the views are suboptimal and the patient is stable, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) may be beneficial and provide additional information about the great vessels. Resuscitative TEE in acute trauma can provide additional diagnostic information beyond existing methods and can influence definitive management decisions for some patients in the trauma bay.[19] In relatively stable patients, computed tomography (CT) is also a component of the trauma evaluation, as this study has a high sensitivity for pericardial or myocardial lacerations, cardiac luxation, and other thoracic injuries. Moreover, CT can help identify the path of a projectile and the location of a foreign body.[20]

Evaluation specific to blunt cardiac trauma is difficult as there are no validated screening criteria for BCI. An ECG, while not standard in evaluating the acutely injured patient, is helpful in demonstrating the presence of new dysrhythmias, which should make a clinician suspicious of BCI, excluding sinus tachycardia. A normal ECG alone has a high negative predictive value for BCI. In addition to an ECG, cardiac enzymes (eg, cardiac-specific troponins) should be considered during routine trauma evaluation. Troponins can help evaluate for the presence of a myocardial contusion or ischemia secondary to a vessel injury and also have a high negative predictive value of a blunt cardiac injury.[21] A normal ECG and troponin within the normal range have been shown to have an approximately 100% negative predictive value for blunt cardiac injury. However, some authorities debate when to perform the troponin and whether performing serial troponins is beneficial.[22] Further evaluation may be needed due to the suspected underlying injury, including angiography for those with infarction patterns on ECG or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to help identify the extent of a myocardial contusion.

Penetrating cardiac injury evaluation should be considered for any individual with an open wound to the thorax. Wounds within the imaginary box defined by the inferior clavicles, inferior costal margins, and mid-clavicular lines are especially concerning. Echocardiography has been shown to have high sensitivity and specificity for cardiac wounds. Aside from physical examination and echocardiography, further evaluation is often unnecessary; however, chest x-rays may help provide the approximate location and presence of foreign bodies.

Treatment / Management

Initially, the management approach for patients with traumatic cardiac injuries should follow ATLS protocol, including airway, breathing, and cervical spine protection. Subsequent treatment should be guided by the type of cardiac trauma identified, primarily blunt or penetrating cardiac injuries.[23]

BCI has many possible patterns, including dysrhythmias, contusions, rupture, valvular injury, and coronary artery injury. Dysrhythmias range from commotio cordis with nonperfusing ventricular fibrillation to stable first-degree atrioventricular blocks. Advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS) management should be initiated for dysrhythmias, excluding other traumatic injuries and alternative etiologies of the dysrhythmia. Any dysrhythmia outside of sinus tachycardia that is presumed new should prompt consideration of further cardiac telemetry monitoring and echocardiography if not already performed. Patients with atrial dysrhythmias have been shown to benefit from treatment, and a beta or calcium channel blocker should be considered for the stable patient. In the unstable patient, electrical cardioversion may be an option if their instability is suspected secondary to the dysrhythmia.[7][24]

Myocardial contusions can present with electrical disturbances or may be found only with an elevated troponin. Treatment is supportive and determined by the severity of other findings, such as hypotension or high-grade dysrhythmias. Evaluation of these patients parallels that of patients with myocardial infarctions, with a similar range of outcomes and complications.[10] Cardiac rupture may be lethal depending on the location and extent of damage to cardiac tissue. Operative repair is indicated with a sternotomy or thoracotomy and potentially cardiopulmonary bypass. Valvular injuries may be repaired depending on the nature of the damage. Certain cases, such as papillary muscle rupture, may require valve replacement.[25]

Coronary artery lacerations or bleeding should be managed operatively to control the involved artery and coronary bypass. In cases where hemostatic coronary artery injuries are suspected, angiography with management based on findings is generally indicated, including stenting or medical management.[26] Using a Foley to close a cardiac wound temporarily allows for rapid transfusion of blood products. There are multiple acceptable means of temporarily closing a cardiac wound during an emergency thoracotomy, including Foley placement, digital pressure, sutures, or staples. Each is acceptable, but only the placement of a Foley can provide a route for rapid resuscitation while also closing the wound.[26] Cardiac wounds may lead to exsanguination if not temporized while awaiting definitive repair. Lacerations can be controlled initially with digital pressure, vascular clamp (atrial wounds), or the insertion of a Foley followed by balloon inflation and light traction. Blood products may be able to be transfused through the Foley, in addition to helping temporize a cardiac wound. Cardiac laceration repair can be achieved using 3-0 polypropylene sutures, typically in running, horizontal mattress or purse stitches. Pledgets or pieces of the pericardium are often used to distribute tension when repairing ventricular wounds.[27]

Penetrating cardiac trauma is more straightforward in management, with operative management ultimately required. If the patient is unstable, a pericardiocentesis can be performed with a catheter placed for intermittent drainage to help temporarily stabilize the patient. A median sternotomy or thoracotomy is used to access the heart so that a pericardiotomy may be performed while avoiding the phrenic nerve. While repairing the wound, proper technique should be used, including obtaining adequate portions of the myocardial wound edges during suturing to prevent tearing tissue, placing ventricular sutures during ventricular contraction to help minimize myocardium tearing, and avoiding ligating coronary arteries when repairing cardiac wounds. Posterior heart lacerations need to be repaired with patience, such as elevating the heart for a continued period to visualize the area and place and tie sutures, as lifting the heart can cause hypotension and potentially cardiac arrest. Although staples have been used instead of sutures to help close the wound, their use remains controversial.[25]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses that should be considered when evaluating patients with cardiac trauma include:

- Cardiac tamponade

- Cardiogenic pulmonary edema

- Cardiogenic shock

- Hemorrhagic shock

- Mitral regurgitation

- Right ventricular infarction [20]

Prognosis

Penetrating cardiac injury management has evolved recently, significantly affecting patient outcomes. Simple clinical observations are no longer accepted, and diagnostic studies, including FAST, transthoracic echocardiogram, and CT scan, have assisted in more precise diagnostic measures. Collectively, the survival rate of penetrating cardiac traumas improved significantly. However, the mortality rate of penetrating cardiac trauma remains as high as 40%.[28]

Complications

The following complications are predicted with cardiac trauma:

- Pericardial effusion

- Abnormal wall motion

- Decreased ejection fraction

- Intramural thrombus

- Valve injury

- Cardiac enlargement

- Conduction abnormality

- Pseudoaneurysm

- Aneurysm

- Septal defect [29]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Acute rehabilitation guidelines regarding posttherapeutic management of patients with cardiac trauma are frequently not strictly adhered to, particularly in terms of documented early assessments by physical therapy and rehabilitation clinicians and direct transfer of patients with traumatic injuries from acute care to rehabilitation. This suboptimal management highlights the necessity for a more systematic integration of rehabilitation therapy during the acute treatment phase of care in patients with traumatic injuries.[30]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education and prevention of cardiac trauma are crucial in reducing the incidence and improving outcomes of such injuries. Educating patients about the risks and preventive measures is essential, especially given that trauma remains a leading cause of death and disability across all age groups, with a significant impact on children and young adults. Patients should be informed about the importance of safety measures, such as wearing seat belts, using protective gear during sports, and adhering to workplace safety protocols. Additionally, public awareness campaigns can highlight the dangers of high-risk behaviors, including driving under the influence and engaging in violent activities, which are common contributors to both blunt and penetrating cardiac trauma.

For individuals at higher risk, such as those engaged in contact sports or high-impact occupations, targeted education can further reduce the likelihood of cardiac injuries. Emphasizing the importance of immediate medical evaluation following any significant chest trauma is critical, as rapid deterioration can occur. Patients should be made aware of the signs and symptoms of cardiac trauma, such as chest pain, shortness of breath, and irregular heartbeats, and understand the necessity of seeking prompt medical attention. Clinicians can also educate patients on the benefits of regular check-ups and early intervention, which can improve the prognosis of cardiac injuries. Preventive strategies, such as the use of advanced protective equipment and adherence to safety guidelines, are vital in minimizing the risk and severity of cardiac trauma.

By fostering a comprehensive understanding of prevention and early detection, clinicians can empower patients to take proactive steps in protecting themselves from cardiac trauma. This approach not only enhances individual patient safety but also contributes to overall community health by reducing the burden of trauma-related morbidity and mortality.

Pearls and Other Issues

Foreign bodies visible externally on patient arrival and suspected to be related to a penetrating cardiac injury should be left in place temporarily to allow for set-up for operative evaluation and care. Otherwise, retained foreign bodies should be removed operatively if contamination or electrical abnormalities exist.[31]

Emergency department thoracotomy is controversial due to survival rates ranging from around 1% to 30%, depending on the patient population. Despite low survival rates, as the alternative is guaranteed death, thoracotomy is still performed in select situations. Individuals with blunt trauma and loss of vital signs are less likely to survive. An emergency thoracotomy should be considered for blunt trauma victims with the loss of pulses for <5 to 10 minutes, depending on the protocol followed. However, survivors have been reported following a loss of pulses for up to 15 minutes. An emergent thoracotomy should be considered for penetrating trauma victims with the loss of pulses <15 minutes, though survivors have again been documented with up to 32 minutes of CPR.[32]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of cardiac trauma requires an interprofessional team, including emergency department physicians, trauma surgeons, cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, radiologists, perfusionists, advanced practitioners, cardiac nurses, intensivists, and pharmacists, all adhering to the ATLS protocol. The initial management involves rapid assessment and stabilization, recognizing the necessity of emergent intervention to reduce morbidity and mortality rates. Emergency physicians and trauma surgeons coordinate to assess and initiate immediate care, including imaging and potential surgical interventions. Cardiologists and cardiac surgeons are crucial for advanced diagnostic evaluations and surgical repairs, ensuring prompt and accurate treatment decisions. Radiologists provide critical imaging interpretations, while perfusionists and cardiac nurses support surgical procedures and postoperative care. Intensivists manage patients in critical care settings, ensuring continuous monitoring and response to complications. Pharmacists ensure appropriate medication management, addressing pain, infection prevention, and cardiac support. Clear and effective interprofessional communication and collaboration are essential to providing seamless, patient-centered care and improving patient outcomes and safety. This cohesive approach ensures that each team member's expertise contributes to timely, comprehensive care, enhancing overall team performance and patient survival rates in cardiac trauma cases.