Continuing Education Activity

Cardiopulmonary bypass has become the standard of care for many cardiac procedures. The procedure is relatively safe if the duration of surgery is not prolonged. This activity reviews the technique involved in performing a cardiopulmonary bypass and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the pre- and post-operative management of patients undergoing this procedure.

Objectives:

- Summarize the indications for cardiopulmonary bypass.

- Describe the technique involved in performing cardiopulmonary bypass.

- Outline the complications associated with cardiopulmonary bypass.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for enhancing care coordination and communication to advance the safe use of the cardiopulmonary bypass procedure and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

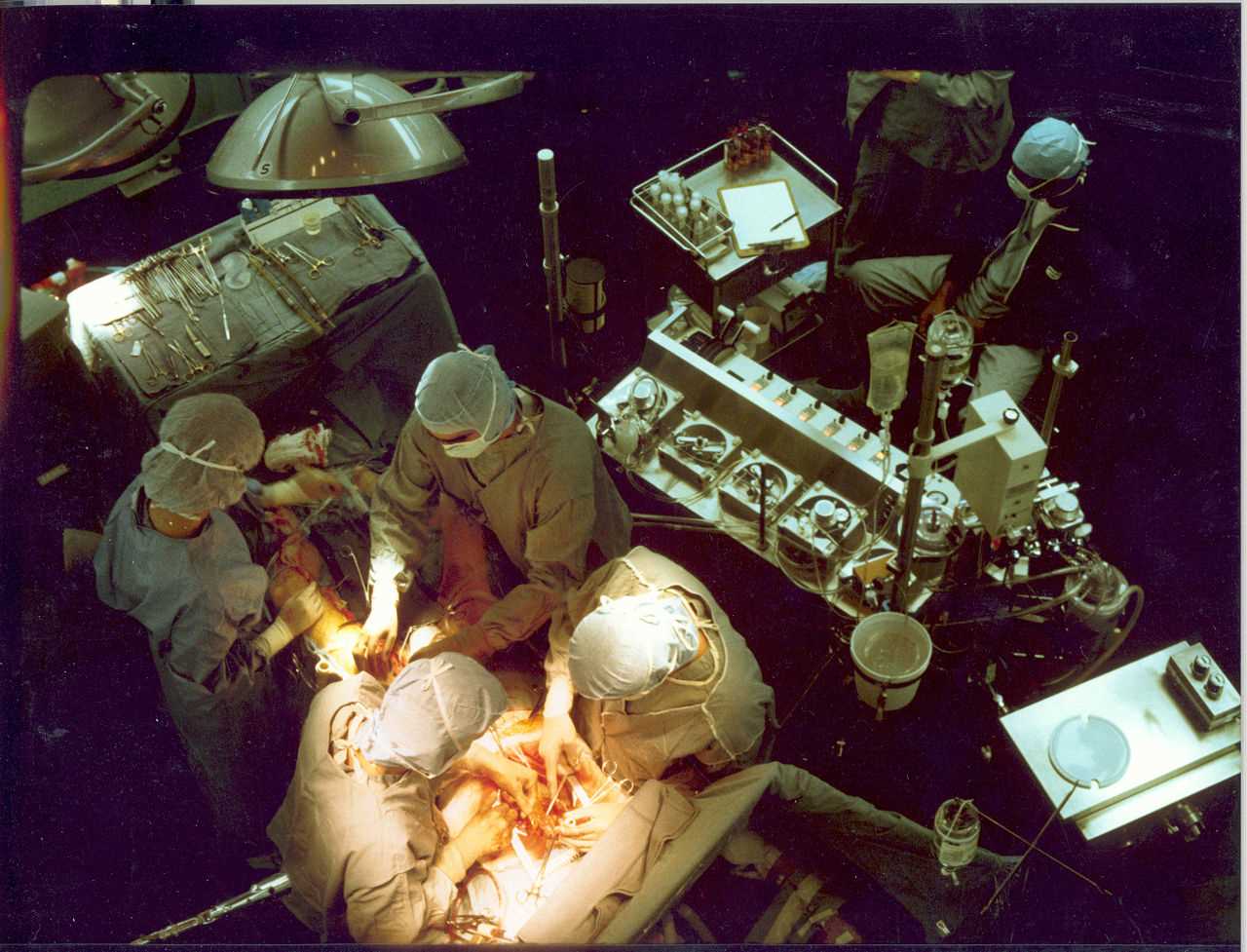

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) answered one of the toughest questions in the history of medicine: Can we operate on human hearts without killing the patient? When heart surgery started, only a handful of conditions were considered feasible for safe performance. This included trauma such as minor tears of the pericardium, heart, and vessels or extracardiac congenital conditions such as coarctation of the aorta and patent ductus arteriosus. The actual start of the new era of cardiac surgery was only achieved when surgeons developed a way to create a bloodless state which enabled the surgeon to open the heart and efficiently repair it without interrupting its essential role, delivering warm, oxygenated blood to the rest of the body's organs.[1][2][3][4]

Indications

The role of CPB could thus be summarized as follows:

- Empty the heart. Drain all the blood out (achieved via venous cannulas).

- Oxygenate the blood. Thus stop the lungs via oxygenators.

- Adjust its chemical and electrolyte contents via a reservoir container.

- Adjust its temperature via the heat exchanger machine.

- Return it to the patient via arterial cannulas.

Also, provide means to ensure the following:

- Save blood lost during surgery and return it to the patient via cardiotomy suckers.

- Prevent distention of the heart during surgery via cardiac vents.

- Deliver cardioplegia and provide myocardial protection (discussed separately).

- Provide safety nets and standby pathways (safety adjuncts). This is all achieved via a closed circuit driven by pumps and connected by tubes.

Contraindications

There is no definite contraindication for CPB; however, in certain situations, surgeons might opt to delay the timing of surgery, bearing in mind the complications/pathophysiology, including conditions such as acute impairment of kidney functions, acute cerebral stroke, chest infection, or acute exacerbations of asthma. In those particular situations, recovery is expected. Accordingly, if the situation permits, it is better to wait and thus improve the outcome and reduce the risk burden.

Equipment

The components of the CBP machine include the following:

- Venous cannula

- Arterial cannula

- Oxygenator

- Reservoir container

- Pumps

- Tubing

- Heat exchanger

- Cardiotomy suckers

- Cardiac Vents and

- Adjuncts such as the level detector, arterial line pressure meter, arterial line bubble trap and filter, cardioplegia line pressure meter, gas line filter, gas flow meter, and one-way valves on cardiac vents.

The circuit is constructed using the components. The CPB circuit (heart-lung machine) is a bit complex; the best way to understand it is to look at it step-by-step rather than looking at the whole picture at once (Figure 1).

- The circuit starts at the right heart side, where all/part of the venous return is drawn into the reservoir via a venous cannula(s). This happens passively by gravity, relying on the difference in height between the patient and the reservoir.

- The blood is then driven via a systemic blood pump or the main pump into the oxygenator, which oxygenates the blood and transforms it into usable blood.

- The next step is returning this blood to the patient, but not all of it will return to the same place. The blood instead is split into two. The normal (oxygenated) blood goes back to the patient via the aortic cannula, which is penetrated by the surgeon in the distal ascending aorta. The cardioplegic blood (oxygenated and with cardioplegia solution added) returns to the patient more proximal on the ascending aorta via the aortic root cannula. This portion of the blood is delivered via a separate pump (the cardioplegia pump) and separately adjusted regarding temperature and pressure.

- Later, when CPB is complete and the heart function is no longer needed to eject blood into the body, an aortic cross-clamp is applied to the proximal aorta. By separating both compartments, the heart will receive only cardioplegic blood, and the body will receive only normal blood (NB).

The rest of the circuit consists of the suckers/vents (Figure 1: violet) and the oxygenator suppliers (Figure 1: green) as follows:

Suckers

Cardiotomy suckers all receive blood from the patient and return it to the reservoir to support the circuit as described are

Vents

Left ventricular vents (aortic root, RSVP [right superior pulmonary vein], apical, pulmonary) follow the same pattern as suckers with one addition of one-way vent valves to prevent adverse pumping of air into the heart

Oxygenator Suppliers

This refers to a gas or water heat exchanger; the former allows the blood to be oxygenated hence substituting the function of the lung, while the latter enables the blood to warm or cool to achieve myocardial protection.

This supreme innovative design of the circuit allows a surgeon to do the following: Empty the heart, stop its beating using cardioplegic blood, stop the lungs and substitute it with the oxygenator, and perfuse the rest of the body with normally oxygenated blood. Hence one achieves a bloodless, still field suitable to perform open heart surgery.

Arterial Cannulas

Types:The aortic cannula must be safe to insert smoothly (atraumatic tip and surface) with no high-pressure gradient jet at the tip that could dislodge atheromatous plaques and be of the suitable size to allow sufficient flow. Various designs of arterial cannulas are available for use. There is nothing termed as the best cannula; each cannula enjoys specific features that suit a particular situation, all cannulas are used in practice, and it is up to the surgeon to assess the situation and decide which to use. The following is a brief description of some of the features and their values.

- Right-angled - prevents perforating the posterior wall of the aorta. However, it can selectively perfuse an arch branch.

- Straight - prevents selective arch vessel perfusion. However, it can penetrate the posterior wall of the aorta.

- Beveled tip - easier insertion; however, it has a higher pressure gradient delivered at the tip.

- Diffusion tip - less pressure gradient allows better perfusion of arch branches yet is slightly more difficult.

- Wire reinforced - allows higher flow for a smaller size cannula and also more immune to iatrogenic dissection.

- Flanges - hemostatic as well as act as anchor points for the purse strings.

Sites and techniques:

Arterial cannulation can be classified as one of the following:

- Central (aorta, LV apex)

- Peripheral (axillary, subclavian, innominate, femoral)

Central cannulation has plenty of value, making it the most commonly used site in practice (Table 1); however, unfortunately, it becomes less favored in certain circumstances, such as the following brief examples:

Aortic arch surgery - Surgeons in the past cannulated the ascending aorta first to achieve a hypothermic circulatory arrest. They then would take out the cannula and reinsert it into the carotid artery to provide antegrade cerebral perfusion. Auxillary artery cannulation can accomplish both with the same cannula hence reducing manipulation and time.

Aortic Aneurysm surgery - Sometimes the aorta is dilated or aneurysmal, and there is a risk of rupture during a sternotomy; thus, using peripheral cannulation first on bypass before opening the chest could be a safer option.

Aortic Dissections - The whole aorta could sometimes be obscured by the false lumen.

Redo Surgeries - Again, sternotomy could entail risks. Thus peripheral cannulation is safer in some circumstances

Minimal invasive surgeries - Avoid the need for standard midline sternotomy altogether.

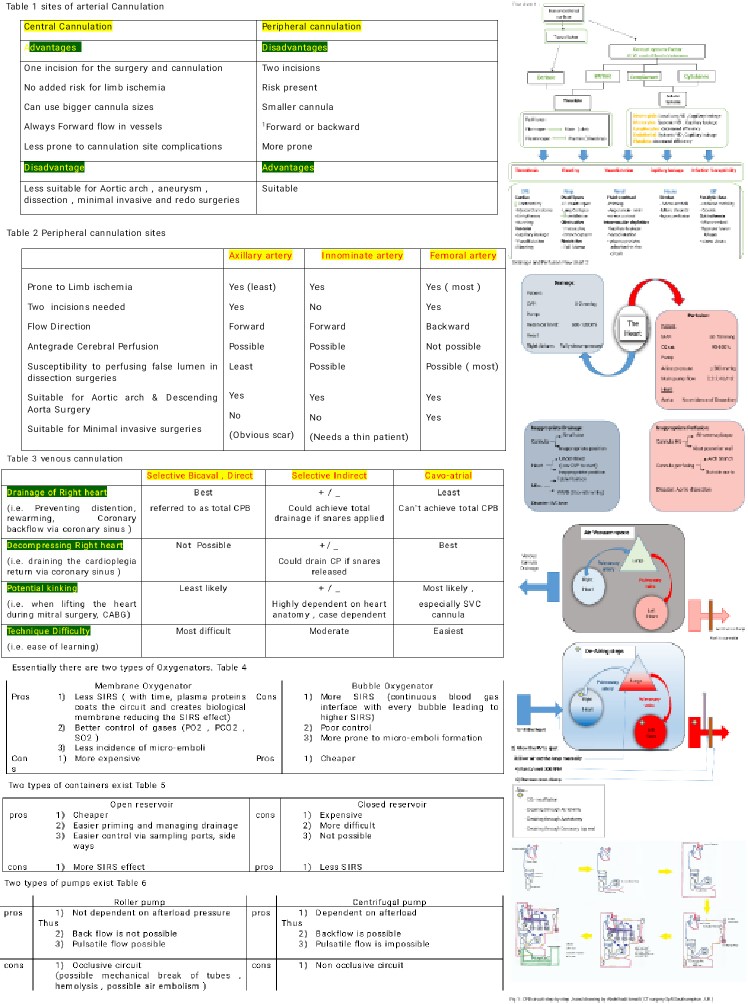

(Table 1: Sites of arterial cannulation)

(Table 2: Peripheral cannulation sites)

Venous Cannulas

Types:Venous cannulas must be easy to insert, of sufficient size to enable acceptable drainage, pliable, and resistant to kinking. Various types of cannulas have been designed to achieve this purpose. Unlike the aortic cannulas, where the different types of cannulas serve more or less the same purpose and could be used almost in all sites, venous cannula designs were made to serve different sites/techniques of venous cannulations.

- Two-stage is used in cavoatrial venous cannulation.

- One stage is used in selective bicaval cannulation indirectly.

- One-stage right-angled is used in selective bicaval cannulation direct (avoids back wall abutting and block).

- Ross basket is the safest regarding IVC tear, has maximum drainage, and is used for right atrial venous cannulation.

Sites and techniques:(Table 3: Venous cannulation)

Normal Blood

Selective cannulation has the following values:

- In right-side surgery (tricuspid, pulmonary), complete total CPB is a must.

- In mitral valve surgery, complete decompression of the right side is a must.

- In CABG decompressing the right heart, better visualization, and better protection (controversy).

Cavo-atrial cannulation has the following values:

- Easiest, fastest

- Least liable for complications

- Few studies suggest partial CPB is more protective of the lungs as compared to total CPB (controversy)

Oxygenators

The role of the oxygenator is by far the most important. It enables stopping the lung and consequently stopping the heart. Essentially, there are two types of oxygenators (Table 4).

Reservoir Container

The reservoir enables managing the chemical and electrolyte contents and allows direct and accurate assessment of the drainage. Two types of containers exist (Table 5).

Pumps

See Table 6: Two Types of Pumps

Tubes

All tubes are made of PVC (polyvinyl chloride), which is non-allergic, non-mutagenic, non-toxic, and non-immunogenic. Also, it must be pliable, flexible, and transparent. The venous tube is 1/2 inch (12 mm); the arterial tube is 3/8 inch (8 mm); the vents and suckers are 1/4 inch (6 mm).

Preparation

Conduct of Bypass

Satisfactory CPB means the pump has successfully managed to take over the function of the heart and the lungs. To achieve that, the surgeon goes through the following steps:

Step 1: Establishing the Circuit (Priming)

Establishes the circuit (as described above) and carries on priming and heparinisation.

As previously described, the circuit's aim is to drain blood from the venous side of the heart via a venous cannula and return it to the heart via an arterial cannula and process the blood in between. Initially, the tubes of the venous( inflow) and arterial (outflow) are in continuity. This is to allow the perfusionist to fill the circuit with fluid from the reservoir and run the main head pump, to expel all air out of the tubes and keep air confined to the top bit of the reservoir. Creating what is referred to as the level below which no air must be detected because this will be the connection between the patient and the heart-lung machine. No air is allowed in there. If air exists on the arterial side, it causes air embolism, and if it exists on the venous side, it creates air lock. Hence arises, the importance of this crucial preliminary step. This process is referred to as priming.

Priming solution constituents vary from one center to another; however, they are not vastly variable. One of the standard protocols is 1 L crystalloid, 500 mL colloid, and 250 mL mannitol. (Studies have shown them to reduce the incidence of kidney dysfunction postoperatively.) Other constituents sometimes added include magnesium (counteracts calcium's deleterious effects ), HCO3 (acts as a buffer), and procaine/lidocaine (enhances membrane stability). Another protocol sometimes used is replacing the crystalloid with blood; this could be cross-matched stored blood from the blood bank or from the patient’s own blood. The latter is referred to as autologous retrograde priming.

Step 2:

Next, it goes on bypass after achieving sufficient priming and heparinization. In other words, the pump starts running while the heart and lungs are still functional.

Step 3:

The surgeon then must be able to confirm the function of both the heart and the lungs is entirely replaced by looking at specific parameters.

Step 4:

If all goes well, the surgeon stops the heart via a proper myocardial protection strategy (described in a different section) and stops the lungs merely by switching off the ventilator.

- Establishing the Circuit: Heparinization

CPB is a non-endothelial circuit. Blood is prone to massive clotting if not well anticoagulated. Accordingly, before going on bypass, IV heparin in a specific dose is given (300 units /kg or 3g/kg). The sufficient level of anticoagulation is judged via checking ACT in theatre.

- ACT greater than 300 sec is safe for Cannulation

- ACT greater than 400 sec is safe for going on bypass

- ACT greater than 480 sec is safe for going on DHCA

If ACT does not or only marginally increases after full heparinization, heparin resistance is suspected. The most common cause is antithrombin III deficiency. After discussing with the surgeon and if a total dose of 600 units of heparin per kg does not achieve ACT >480, recombinant ATIII concentrate should be considered. Otherwise, fresh frozen plasma may be administered as it does contain anti-thrombin III.

(ACT is checked every 30 min during the operation. If it falls below 480 sec extra 500 units are given.)

At the end of the operation, Heparin is reversed by giving Protamine (1 g/100 units of heparin given). Protamine is obtained from salmon sperm and is used to reverse heparin anticoagulation. The positively charged molecules form 1:1 complexes with heparin. Protamine is associated with hypotension, pulmonary vasoconstriction, bronchoconstriction, reduced cardiac output, and even anaphylaxis. Hypotension may also be rate of administration dependent.

Going "On Bypass"

The surgeon carries on arterial cannulation and venous cannulation, then connects the arterial and venous cannulas to the pump. As previously explained, both sides of the circuit are in continuity, so the surgeon must "divide the lines." Before dividing lines, the surgeon must confirm two things with the perfusionist:

- The pump is off: otherwise, the pump will push against a closed clamp leading to machine breakage

- The venous line is clamped: otherwise, the fluid in the venous line will all siphon back into the reservoir.

Before connecting the lines to the cannulas, the surgeon instructs the perfusionist to:

- Arterial cannula: to push some fluid to de-air the connection completely (i.e., "come around").

- Venous cannula: to pull back some fluid, reduce the length of tubes, and make sure it sits nicely.

Two features to confirm after the surgeon connects the arterial line tube to the aortic cannula:

- Good swing: meaning the cannula is in continuity with the bloodstream (i.e., inside the aorta).

- Good pressure: meaning it is not on an inappropriate site. (e.g., back wall, dissection lumen).

It is always best to connect the arterial cannula first for several reasons. First, to be able to transfuse volume into circulation provided should the patient get hemodynamically compromised at any point. Also, sometimes venous cannulation leads to atrial irritation and supraventricular arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation, which may be poorly tolerated with certain heart conditions such as LV hypertrophy or aortic stenosis. Additionally, atriotomy to insert the venous cannula will always lead to blood loss, which could compromise the patient. Provided the Arterial cannula is ready and connected, the surgeon can then quickly correct this by instructing the perfusionist to transfuse volume. Once the connections are all satisfactory, the surgeon asks both the anesthetist and the perfusionist if they are happy to go on bypass. If all is well, they give the go-ahead order to go "on bypass."

An example of a typical dialogue is:Surgeon: ACT ok? Anesthetist: ACT satisfactory. Surgeon: Cannulating (The anesthetist could instruct to wait if pressure is high.) Anesthetist: Go ahead. Surgeon: Dividing the lines. Perfusionist: Off and clamped. Surgeon: Connecting A-line, come around please, Stop, A-line connected. Perfusionist: Good swing and pressure.Surgeon: Cannulating atrium, return losses, please. Perfusionist: Transfusing. Surgeon: Take back, please; connected, ready to go on bypass? Perfusionist/anesthetist: All good. Surgeon: On bypass, please.

Confirming Satisfactory Bypass

To confirm satisfactory CPB, specific parameters must be checked. Collectively, these can be grouped into drainage and perfusion.

(Flowchart 2)

For intracardiac repair, cross-clamping the aorta is essential, which renders the heart ischemic. Cardioplegia is a method of myocardial protection where the heart is perfused with a solution to cause electromechanical arrest - which in turn - reduces myocardial oxygen consumption. The cardioplegia cannula is inserted proximally, while the aortic cannula is distal to the clamp. A separate pump delivers cardioplegia either antegrade into the aortic root or retrograde into the coronary sinus or both. TEE can guide the placement of the balloon-tipped retrograde cannula into the coronary sinus. Retrograde cardioplegia alone results in inadequate right ventricle protection. However, retrograde cardioplegia may be compulsory in addition to anterograde or ostial cardioplegia when aortic insufficiency is present. When there is aortic insufficiency, anterograde cardioplegia may 'leak' through the incompetent valve resulting in inadequate cardiac protection due to insufficient delivery of the solution and myocardial stretch of the left ventricle. In this scenario, retrograde cardioplegia may also be used. Ostial cardioplegia is given when there is severe aortic regurgitation.[5]

Technique or Treatment

Weaning Off Bypass

The steps of weaning could be described as the reverse of conducting bypass in the following manner:

Step 1

The surgeon resumes electrical and mechanical activity of the heart and allows blood flow to the lungs, allowing both organs to function partially while the pump still running. Restarting the heart is performed by rewarming, de-airing, and placing epicardial pacing (discussed in a separate chapter). Reperfusion of the lungs occurs simply by re-ventilating.

Step 2

The surgeon must be able to confirm the function of both the heart and the lungs by looking at specific parameters (e.g., arterial blood gas, cardiac output).

Step 3

If all is well, the surgeon instructs the perfusionist to gradually slow down the pump until fully off the machine. The arterial and venous lines are clamped, and both the lung and heart functions are monitored for a few more minutes.

Step 4

The surgeon dismantles the circuit step by step, but only if the heart and lung function is back to normal.

- Restarting the heart: Rewarming

The process of rewarming is essential to re-establish metabolism of the cardiac myocytes. This process takes longer (0.3-0.5 C /min) than the cooling process (0.5-1.5 C /min) due to the physical properties of body fluids. Cooling is achieved systemically via the heat exchanger and topical application of cold crystalloid/ice slush on the myocardium. Similarly, rewarming is achieved systemically via the heat exchanger and the use of the ”bear hugger” to warm the lower extremities. Caution is required during rewarming; one should not rewarm too quickly to avoid the creation of microbubbles (Boyle law) and also should not overheat as this can lead to denaturation of some plasma proteins.

- Restarting the heart: De-Airing

This is a vast topic and a crucial step in the process of weaning (to be explained in detail in another chapter). Nevertheless, in short, de-airing aims at expelling all air out of the heart and great vessels before allowing the heart to take over circulation independently. Residual air in the heart and aorta can embolize to any organ and cause severe damage. A major concern, however, is air embolizing to the coronary or carotid arteries because they are the first two branches of the aorta. The right coronary artery, in particular, is vulnerable due to its higher position anteriorly, making it more susceptible to air embolism via the coronary ostium. If air does embolize down the right coronary, this will be evident in the form of right ventricle distension. The CPB pump provides means to deal with any “air particles" via simple maneuvers such as escalating pump flow and increasing pressure to expel air down the system where it is less serious, or one may require more drastic maneuvers such as going back on bypass and/or conducting antegrade/retrograde cerebral perfusion. Therefore, it is essential to ensure satisfactory de-airing before dismantling the circuit.

When the heart is fully decompressed, the distance between the venous cannula to the cross-clamp, including the right heart, pulmonary arteries, lung parenchyma, pulmonary veins, and left heart, is supposed to be empty of blood. However, it will contain some air. This air will be exaggerated with any breach created by the surgeon (even as simple as CABG) since it will suck ambient air into this space. Sources of air finding a way to this space during cardiac surgery could be classified as surgical (atriotomy, aortotomy, cannulation site), anesthetic (CVC line), CPB pump (exhaustion of reservoir level, unsecured stock ports, cavitation), and natural dead space. The de-airing process is summarized in Flow Chart 3.

Confirming Suitability for Weaning

Before dismantling the circuit, the surgeon must confirm the heart and lungs are ready to resume their functions independently. The following is a summary of parameters.

- Two “No": No conditions include graft failure, valve leakage, and dissection. No residual air.

- Two “satisfactory”: Satisfactory pacing. Satisfactory ventilation

- Two “Physiological”: Physiological temperature (35 to 37 C). Physiological gases (ABG, K+, po2).

Gradual Comedown

The perfusionist starts to gradually limit the amount of blood coming back from the patient by applying gradual clamping to the venous line. Doing this alone will lead to more blood going into the patient than coming back, In other words, filling the heart. This is done until a satisfactory contraction is achieved, reaching the highest point of the Frank-Starling curve. At such point, the perfusionist starts to slow down the flow of the main head pump as instructed by the surgeon. This will limit the blood flowing back to the heart. This goes on gradually until the venous line is fully clamped and the main head pump is fully switched off

Dismantle the Circuit

This is done in a stepwise manner in the following order. Venous cannula out (but leave the purse string intact), then root vent out, then aortic cannula out (after giving protamine and satisfactory filling). Throughout the procedure, the surgeon keeps an eye on the heart parameters, bearing in mind the situation might necessitate going back on the bypass at any time. To enable that, certain precautions are done. Fill the venous line with crystalloid to re-prime it (siphon venous line). The perfusionist checks the heparinization, occlusion, and reservoir levels. The surgeon leaves the atrial purse strings ready to reuse if needed.

Complications

CPB circuit is a non-endothelial surface. Contact with blood elicits a series of inflammatory responses, leading to widespread systemic effects. The pathophysiology of CPB can be briefly summarized in the following sentence:

Five plasma proteins and five cellular systems activate to lead to five principal effects on five cardinal systems.

See Flowchart 1: CPB pathophysiology

Clinical Significance

The development of CPB has allowed cardiac surgeons to operate on all types of congenital and acquired heart defects. The technique is now routinely used all over the world with great success. It is important, however, to remember that CPB is not without complications, many of which can be life-threatening. To reduce the risk of complications from CPB, many surgeons also perform off-pump heart surgery.[6][7][8][9]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

CPM is a well-established technique for performing a number of open-heart procedures. The procedure is only done by the cardiac surgeon. However, the technique is associated with a number of complications that may be managed by the intensivist, internist, nephrologist, neurologist, and gastroenterologist. The procedure can be associated with a stroke, multiorgan failure, bleeding, infection, and renal failure. These patients are monitored in a cardiac surgical unit by ICU nurses until they are stable.