Continuing Education Activity

Caroli disease is a rare inherited disorder involving segmental dilatation of large, intrahepatic bile ducts which appear as cysts on imaging and histopathologic exam. The gene involved is the same gene responsible for autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD); hence, these conditions commonly co-occur. Caroli disease is usually diagnosed during adolescence, and patients typically present with recurrent episodes of cholangitis. This activity describes the pathophysiology of Caroli disease and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Describe the typical history and physical exam findings of a patient with Caroli disease.

- Summarize the treatment options for Caroli disease.

- Detail the evaluation of a patient with Caroli disease.

- Review the importance of enhancing care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by Caroli disease.

Introduction

Caroli disease is also known as congenital communicating cavernous ectasia of the biliary tree, is a rare inherited disorder involving segmental dilatation of large intrahepatic bile ducts. [1] Caroli disease can be diffuse or limited and can present in a sac that produces cystic structures that communicates with the biliary tree. Classic Caroli disease is characterized by recurrent episodes of cholangitis and the absence of periportal fibrosis and is usually diagnosed during adolescence. Caroli disease occurs sporadically with no family history of the condition, although rare cases of autosomal dominant inheritance and association with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease have been reported. [2] Classic Caroli disease involves the malformation of the biliary tract whereas Caroli syndrome refers to the presence of associated congenital hepatic fibrosis.

Caroli syndrome is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern and is associated with autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD). Treatment is supportive with antibiotics and if indicated, endoscopic treatment with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for obstruction or impaction.[3][4]

Etiology

Caroli disease was first described in 1958 by Dr. Jacques Caroli, a French gastroenterologist who saw "nonobstructive saccular or fusiform multifocal segmental dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts." It is now known as a genetic disorder involving the PKHD1 gene (polycystic kidney and hepatic disease 1), which affects a protein called fibrocystin. This protein is expressed in multiple organ systems: the renal tubular cells, liver cholangiocytes, and the pancreas. Genetic abnormalities in this protein result in fibrocystic changes in the kidney and liver. Caroli disease is frequently seen with autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD).[5]

Epidemiology

The exact numbers for its incidence and prevalence are not known as the condition is rare, but it is estimated to occur in approximately 1 in 10,000 live births. Males and females are equally affected, and it is more common in people of Asian descent. Peak incidence is in early adult life, and more than 80% of patients present before turning 30 years of age.

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiologic basis of this disorder is not completely understood, but it has been reported that Caroli disease is a genetic disorder involving a mutation of the PKHD1 gene that is also responsible for the fibrocystin protein. It is a large gene present on chromosome 6p12 and is expressed primarily in the kidney and with lower levels in the liver and pancreas. More than 100 mutations in this gene have been recorded, and the majority of the affected patients have compound heterozygosity for this gene, meaning both their alleles have 2 different mutations rendering the gene defective and leading to an abnormal fibrocystin protein. This reflects the diversity of the mutation base that the PKHD1 gene experiences.

In the liver, this protein is part of the cilia on the luminal side of cholangiocytes and is an important receptor in the protein signaling pathway which controls bile composition. It senses mechanical, chemical, and osmotic stimuli in the bile which, through complex intracellular signaling pathways, alter the composition of the bile. This protein also has a role in the normal development of the liver and kidneys through controlling cell proliferation. Therefore, it is understandable that complete absence, or a major abnormality of this protein, would cause structural damage to the liver parenchyma as seen in gross cystic dilatations seen in Carolis disease ultimately leading to liver fibrosis. This cystic dilatation leads to biliary stasis and sludge, which cause intra-hepatic lithiasis and obstruction, which present early in the form of cholangitis.[6][7][8]

Histopathology

The defective fibrocystin gene manifests early during organ development. It leads to remodeling of the ductal plate during embryogenesis as it matures into a branching biliary tree proximal to the portal vein tracts, and effects enhance over time. On a microscopic level, there is dilatation of large bile ducts with marked peri-ductal inflammation, bridging fibrosis, and soft tissue protrusions into the dilated ducts. These dilatations are intra-ductal and in communication with the extra-hepatic tree. This can sometimes be limited to only one lobe; the left lobe is most common. When congenital hepatic fibrosis (CHF) develops, the microscopic features involve fibrosis and enlarged portal tracts, and hypoplastic portal vein branches with abnormal branching angles.

History and Physical

Caroli disease can affect both the kidneys and liver; therefore, clinical manifestations of the disease appear as renal and hepatic complications. Since kidneys are the organ most affected, the first presentation is in the form of polycystic kidneys noted in neonates (ARPKD). The hepatic abnormalities occur later in life as there is relatively less expression of the affected fibrocystin gene in the cholangiocytes as compared to the renal tubular cells.

In Caroli disease, there is biliary stasis and sludge formation leading to obstruction of bile flow. Hence, patients typically present with episodes of recurrent bacterial cholangitis: abdominal pain, fevers, chills, and jaundice much like signs of ascending cholangitis. Pruritis is also commonly reported, it is caused by hyperbilirubinemia from intrahepatic cholestasis. Rarely the disease presents at an older age, after the development of hepatic fibrosis, and patients present with symptoms and signs of portal hypertension such as ascites and variceal bleeding. Patients with Caroli disease are at an increased risk for the development of cholangiocarcinoma.

The physical exam may show right upper quadrant tenderness with a negative Murphy's sign. Hepatomegaly due to gross enlargement due to cystic disease is also seen commonly along with scleral icterus. After the development of hepatic fibrosis, shifting dullness and fluid thrill indicative of ascites can be appreciated. Other signs of liver cirrhosis like spider naevi are also seen.

Evaluation

Laboratory workup will show leukocytosis. In LFT abnormalities, the most common is elevated alkaline phosphatase and direct bilirubin which is consistent with a cholangitis pattern. The hepatic synthetic function is usually preserved.[9][10][11]

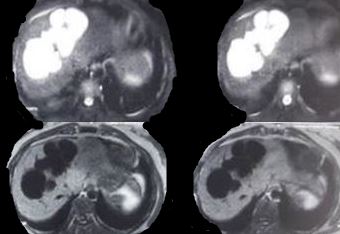

Findings across different imaging modalities are the same. Ultrasonography is usually the first test and shows saccular dilatations of intrahepatic ducts. CT abdomen also shows a dysmorphic liver with gross dilatations and sometimes, a characteristic "central dot sign," which is a dark cystic dilatation around a central bright spot marking the portal tract. Intrahepatic bile duct canaliculi may also be seen. Cholangiography with either ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) or MRCP (magnetic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) shows non-obstructing cystic dilations that communicate with the biliary tree. The advantage of ERCP is that of therapeutic removal of an impacted stone using sphincterotomy and balloon sweep.

Liver biopsy is rarely done and, when performed, the indication usually is to look for evidence of associated hepatic fibrosis.

Treatment / Management

The mainstay of therapy is supportive and individualized according to the presentation. Cholangitis due to biliary obstruction is treated with antibiotics that cover gram-negative rods and anaerobic rods. Adequate biliary drainage may be required in the form of biliary stent placement through ERCP or IR-guided percutaneous trans-hepatic catheter (PTC) placement. PTC is usually more effective at draining intra-hepatic obstruction and patients sometimes require indwelling catheters with periodic flushing and changing of the catheter. Ursodeoxycholic acid is used to treat severe cholestasis. Some authors have recommended segmentectomy, lobectomy, or hepaticojejunostomy depending on the range of cystic formation for the treatment of Caroli disease. [12]

Once hepatic fibrosis sets in, it leads to portal hypertension and its sequelae of variceal bleeding and recurrent ascites which should be managed as they are when related to liver cirrhosis, for example, with non-selective beta-blockers, endoscopic band ligation, and diuretic therapy for ascites. Liver transplantation is the only definitive treatment available at this time for Caroli syndrome. There are 3 indications for liver transplantation in Caroli syndrome: hepatic decompensation, recurrent cholangitis that is unresponsive to intervention, and development of focal adenocarcinoma.[13]

Timely surgical treatment is of utmost importance in view of the grave prognosis of cholangiocarcinoma. Studies have shown excellent long-term outcomes with liver resection in unilobar and liver transplant in diffuse Caroli disease complicated with cholangitis and/or portal hypertension. [14]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses based on clinical presentation include ascending cholangitis or acute cholecystitis. On imaging, saccular dilatations may mimic choledochal cysts, hepatic abscesses, and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Type V choledochal cysts are intra-hepatic cystic dilatation of the biliary system but without the genetic abnormality of Caroli disease. However, according to the Todani classification, Caroli disease is grouped with type V choledochal cysts.

Prognosis

The prognosis for Caroli disease varies according to the extent of underlying genetic abnormality (gene deletion or mutation) and also the number of different organ systems involved. Recurrent biliary obstruction and fibrosis cause significant morbidity, and liver transplantation is the only definitive treatment at this time. Patients with Caroli disease are at an increased for cholangiocarcinoma which has a poor prognosis

Complications

Complications are recurrent bouts of cholangitis, intrahepatic calculi, abscess, and development of cholangiocarcinoma. [1]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Caroli disease is a rare genetic disorder that is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a geneticist, gastroenterologist, liver specialist, urologist, nephrologist, radiologist, and transplant surgeon. The mainstay of therapy is supportive and individualized according to the presentation. The key feature of the disease is recurrent cholangitis and hence patients need a drainage procedure.

Since there are multiple cysts, the patient may develop recurrent episodes of cholangitis, and lobectomy or liver transplant may be required in that case.

Chronic cases are usually managed medically. The aim is to prevent recurrent ascites and variceal bleeding. The primary care provider and nurse practitioner should regularly assess liver function and control the ascites with diuretic therapy. The patient's name should be placed on the liver transplant list as soon as possible because donors are in short supply. The transplant nurse should be consulted to educate the patient on the process of getting a new liver.[15][14]