Continuing Education Activity

Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) is a zoonotic disease caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. This is a vector-borne illness spread by the triatomine bug. This activity describes the evaluation and management of Chagas disease and reviews the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the triatomine bug as a vector in the etiology of Chagas disease.

- Describe the histopathology in the acute and chronic phases of Chagas disease.

- Review the use of nifurtimox and benznidazole in the treatment of Chagas disease.

- Summarize the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to educate the patients on the methods used to prevent Chagas disease.

Introduction

American Trypanosomiasis, also known as Chagas disease, is a potentially life-threatening zoonotic illness caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. The disease is most commonly seen in Central and South America, Trinidad, and the southern United States. However, it is less common outside of rural areas where vectors are commonly found in rustic housing. The vector-borne disease is transmitted through vertical transmission between mother and fetus or via contact with contaminated feces/urine of the reduviid bug (triatomine bug, kissing bug) and hence serves as the intermediate host for the parasite. Other modes of transmission include transfusion of blood products, transplant of the infected organ, or by consumption of infected food or drinks. Major complications of this disease includes cardiomegaly, gastrointestinal disease, and in some case peripheral neuropathy.[1]

Etiology

Chagas disease is a vector-borne disease commonly transmitted through contact with contaminated feces/urine of the reduviid bug, also known as the kissing bug or triatomine bug. It is this insect which in turn carries the causative agent, the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Currently, there are 11 different species of the triatomine bug. The most common species in the southern United States are Triatoma sanguisuga and Triatoma gerstaeckeri. The main vectors for Mexico, Central, and South America are Rhodnius prolixus and Triatoma dimidiata. Both sexes of reduviid bug take its blood meal at night, but female bugs must take blood meals to lay their eggs. As it takes the meal or even after the meal, they defecate and expels parasites in the feces/urine near mucous membranes, commonly the mouth or eyes. The parasite then enters through the mucous membrane, or through an open bite wound. Feces of infected reduviid bugs carry the largest number of the infectious trypomastigote form.[2]

Other mode transmissions include:

- Vertical transmission from mother to fetus leading to congenital Chaga's disease

- Organ transplantation

- Transfusion of blood and blood products

Epidemiology

Chaga's is endemic in Latin America, from the southern United States to northern Argentina and Chile[3]. However, the distribution of the disease is changing due to the relocation of individuals from the endemic countries. Domestic and wild mammals are a common host for this parasite. The major route of transmission occurs through infected reduviid bugs, which can be found in cracks indoors or the roofs of substandard housing made from mud, straw or palm thatch. Outdoor locations include animal nests. Other modes of transmission include blood transfusion (before 2007), vertical transmission from mother to child, laboratory transmission, and organ transplant from infected patients. Children are most commonly affected, followed by women, then men.

Pathophysiology

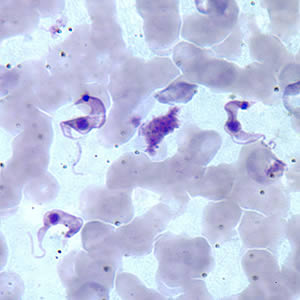

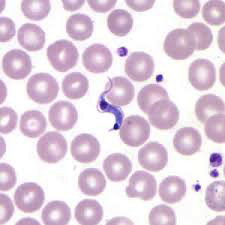

After the parasite enters through an open wound or mucous membrane, the infectious trypomastigote is found in the bloodstream plasma. The amastigote stage of the parasites is found inside pseudocysts located in muscle or nerve cells. There is a predilection for the myocardium or myenteric plexus of the gastrointestinal tract, where it replicates by binary fission. There are three phases of the disease: acute, indeterminate and chronic. In acute infection, symptoms can occur immediately following infection and can last approximately 2 months. Chronic infections can last for years.

Histopathology

T. cruzi, in its leishmanial form, enters macrophages through phagocytosis and initially lack flagella. Then it multiplies in the cytoplasm. As it transverses the gastrointestinal tract, it becomes flagellated in the midgut. Finally, it becomes the infective form in the hindgut. Leishmanial forms can be seen on fixed macrophages with aspiration from spleen, lymph node, bone marrow, or liver. Leishmanial forms can also be seen in rows or cyst-like dilation within the myocardial fiber.

Acute phase: can last from 8 to 12 weeks due to the circulation of the trypomastigotes. Histologically the primary lesion has numerous histiocytes, inflammatory cells, and areas of fat necrosis. Multiplication occurs in nearby macrophages and will cause invasion of smooth and cardiac muscles, glial cells, neurons, and fat cells.

Chronic phase: usually start with an indeterminate form for the first 10 to 30 years of the phase, where the patient will have positive serology but will be asymptomatic. Eventually, progresses to determinant form which may involve the heart and gastrointestinal tract.

Heart disease: generalized hypertrophy and dilation, mural thrombus commonly seen in the right auricle and apex of the left ventricle. Microscopically will show chronic fibrosis, focal area of necrosis and granular degeneration, and interfibrillar edema.

Gastrointestinal (GI) disease: megacolon and megaesophagus due to fibrosis and degeneration of autonomic ganglia in the myenteric plexus.

History and Physical

Intense local inflammation and/or 2 months of uniocular conjunctivitis, known as Chagoma/Romana's sign.

Acute phase lasts for approximately 2 months following infection. May present with fever, edema, lymphadenopathy, anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, ECG abnormalities, central nervous system (CNS) involvement, and death.

Indeterminate phase: Asymptomatic

Chronic phase: Thirty percent of patients may have cardiac involvement and may present with fever, cardiomegaly, apical aneurysms and/or ECG abnormalities. Ten percent of patients may have gastrointestinal tract involvement and may present with fever, megaesophagus, megacolon due to the destruction of myenteric plexus, and constipation.[4]

Evaluation

Diagnosis during the acute phase is made by detecting the parasite microscopically, from a fresh preparation of anticoagulated blood or buffy coat, due to the high level of parasitemia. However, levels may decrease within 90 days of infection and may be undetectable by microscopy, as the sensitivity of the test decreases and as the disease progresses from acute to chronic. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is another diagnostic tool that may be used during the acute phase, monitoring for acute infection in organ transplant recipients or following accidental exposures. PCR assays can demonstrate positive results days to weeks before a peripheral blood smear detects circulating trypomastigotes. Detection of IgG antibodies to T. cruzi can be used to demonstrate chronic infections.[5]

A chest x-ray may show heart involvement with cardiomegaly.

ECG findings may include intraventricular blocks, particularly a right bundle branch block and/or on the left the anterior fascicular block and diffuse ST-T changes.

Treatment / Management

Treatments for the Chagas disease include nifurtimox and benznidazole, with more than 80% success during acute phase; but, with no effect on the amastigote stage. Supportive therapy for the chronic phase is dependent on which organ system is involved.

Differential Diagnosis

- Oesophageal motility disorders

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Pearls and Other Issues

There is currently no vaccine for this disease. The main methods for prevention of transmission include education, improved housing, vector control using bed netting, and screening of donated blood and children in endemic areas.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of chagas disease is complex and best done with an interprofessional team that consists of an infectious disease expert, cardiologist, emergency department physician, gastroenterologist, nurse practitioner and an internist. The disorder is very rare in North America and may be encountered in people visiting the US from South America. The disorder can be treated but most patients have severe residual sequelae. There is currently no vaccine for this disease. [6][7]The main methods for prevention of transmission include education, improved housing, vector control using bed netting, and screening of donated blood and children in endemic areas.[8]