Continuing Education Activity

Torticollis, also known as a twisted neck, is the contraction or contracture of the muscles of the neck that causes the head to tilt to one side. It is accompanied by rotation of the chin to the opposite side with flexion. Usually, torticollis is not a diagnosis but rather a manifestation of a variety of underlying conditions. It can be congenital or due to acquired causes. It can occur at any age, depending on the etiology. The congenital form of torticollis usually presents within a few weeks after birth. Most of the time, it presents as an isolated condition. The diagnostic basis is on the clinical examination findings, and the mainstay of treatment is physical therapy. Surgical management is an option only when medical and physical management does not show the desired results or for cosmetic reasons.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of torticollis and the medical conditions and emergencies associated with this manifestation.

- Review the evaluation of torticollis.

- Summarize the treatment and management options available for torticollis.

- Outline interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance torticollis and improve outcomes.

Introduction

The clinical term "torticollis" comes from two Latin words: tortum collum, which means twisted neck. Usually, torticollis is not a diagnosis but rather a manifestation of a variety of underlying conditions. It can result from congenital or acquired causes. It can occur at any age, depending on the etiology.

Congenital torticollis is defined as a contracture or fibrosis of the Sternocleidomastoid muscle, on one side, leading to a homolateral inclination and contralateral rotation of the face and chin.[1][2][3] Congenital torticollis usually manifests in the neonatal period or after birth.[4] The worldwide incidence rate of congenital torticollis varies between 0.3% and 1.9%, other studies indicate a ratio of 1 per 250 newborns being the third congenital orthopedic anomaly, more frequently following congenital hip dysplasia and the calcaneovalgus feet.[5] Congenital torticollis may be accompanied by congenital hip dysplasia in an incidence of up to 20%.[5] There is a male to female predominance with a 3 to 2 ratio, and it is more common to the right side. The diagnostic basis is usually on physical exam findings. This condition requires differentiation from other forms of congenital or acquired torticollis. Congenital torticollis is the primary condition of the muscle, which is detected at birth or in the first weeks of life. The acquired torticollis are, for example, congenital skeletal anomalies, traumatic conditions, infections, inflammation of adjacent structures, tumoral conditions, ocular, and neurological dystonias.[6] The mainstay of treatment is physical therapy. Surgical management is necessary when physical therapy fails to provide results or for cosmetic reasons.[7][5][8][9]

Etiology

The etiology of congenital torticollis remains unknown, although there are several theories. However, there is no proof for any of them. The most cited are ischemia, trauma during childbirth, and intrauterine malposition (pelvic position).[10]

The most common cause is possibly due to the result of an intrauterine deformation. It is likely to occur in scenarios that are associated with limited intrauterine space such as first pregnancies, decreased amniotic fluid volume, or uterine compression syndrome.

The other causes of congenital torticollis are positional deformation, vertebral anomalies, unilateral atlantooccipital fusion, Klippel-Feil syndrome, unilateral absence of sternocleidomastoid, pterygium colli.[11]

The most common form of torticollis in pediatrics is Congenital muscular torticollis. It is associated with abnormalities of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

The muscles of the neck form a complex system. Schematically, two levels are distinguished: superficial (long neck muscles) and deep (paravertebral muscle). The sternocleidomastoid is the most targeted muscle; it is in the anterior region of the neck, where it forms a visible and palpable mass. Its insertions on the sternum (sternum furcula) and clavicle (two-thirds medial) occipital region (two-thirds side of the neckline) and mastoid apophysis, their fibers having an obliquely upward and outward direction. Its action: performs contralateral rotation, ipsilateral inclination, and flexion of the head. This motor activity results in the tilting of the head and neck toward the side of the affected muscle and rotation to the opposite side. The condition typically gets diagnosed during the neonatal period or infancy.[8]

Epidemiology

The worldwide incidence rate of congenital torticollis varies between 0.3% and 1.9 %; other studies indicate a ratio of 1 in 250 newborns being the third congenital orthopedic anomaly. There is a preponderance to male sex and first pregnancy.[3][4]

A 2% incidence of congenital torticollis in traumatic deliveries and 0.3% in non-traumatic deliveries.[12] In pelvic presentations, about 19.5%, forceps, suction cup represent 56 %.[3][4] Other data reported an incidence of 53% in children whose mother was primiparous, and there was a high occurrence of traumatic childbirth. It is usually identified in neonates by age 2 to 3 weeks and can persist until the age of 1 year. It is typically unilateral, but rarely can be bilateral. There is a visible, palpable swelling known as a sternomastoid tumor, which appears in 50% of cases.[13]

Congenital muscular torticollis categorizes into three types:

- Postural (20%) – Infant has a postural preference but no muscle tightness or restriction to passive range of motion

- Muscular (30%) – Tightness of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and limitation of passive range of motion

- Sternocleidomastoid mass (50%) – Thickening of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and restricted passive range of motion

Pathophysiology

In congenital muscular torticollis, the palpable mass in the sternocleidomastoid muscle is mostly made up of fibrous tissue. This mass usually disappears during infancy and is replaced by a fibrous band. The muscle biopsies and MRI studies of the mass revealed that there could be a component of muscle injury, possibly due to compression and stretching of the muscle.

The venous neck compression during childbirth may also have contributed to the decreased blood supply and subsequent compartmental syndrome. Histological studies of material collected at delivery showed edema, muscle fiber degeneration, and fibrosis. These results corroborate the presence of compartment syndrome.[3][11]

Histopathology

The basic abnormality of congenital torticollis is endomysial fibrosis with collagen deposition and accumulation of fibroblasts around the muscle fibers that lead to muscle atrophy.[14][13]

On gross examination, there are no hemorrhages or necrosis. On the microscopic view, there is a diffuse proliferation of uniform fibroblasts and myofibroblasts along with degenerative skeletal muscle fiber and scar-like collagen. It stains positive for Vimentin and actins.

History and Physical

The evaluation of a newborn should include an exhaustive clinical history, the existence or otherwise of a history of oligohydramnios, a traumatic delivery or pelvic presentation, and a thorough physical examination with particular attention to sternocleidomastoid palpation.

The findings include decreased range of motion and a painless swelling over the side of the neck; these are evident in neonates aged 2 to 3 weeks. If the mass is small or missed in the neonatal period, infants usually present with the head tilted and flexed to the side of the lesion. There is diagnostic confirmation in 50% of cases before two months; parents flag most cases, and some correlates with plagiocephaly but may vary depending on the nodule detected. It may grow for two months until it reaches the approximate size of an almond when it begins to regress and may disappear entirely until the eighth month of life.[15]

In older children, the sternocleidomastoid muscle appears thickened and condensed along its length, which leads to restriction of rotation and lateral flexion of the neck. Due to these rotational changes, there can be flattening of the head called positional plagiocephaly. It can correlate with other musculoskeletal abnormalities such as positional musculoskeletal deformities including metatarsus adductus, calcaneovalgus feet, and developmental dysplasia of the hip, brachial plexus palsy.[2]

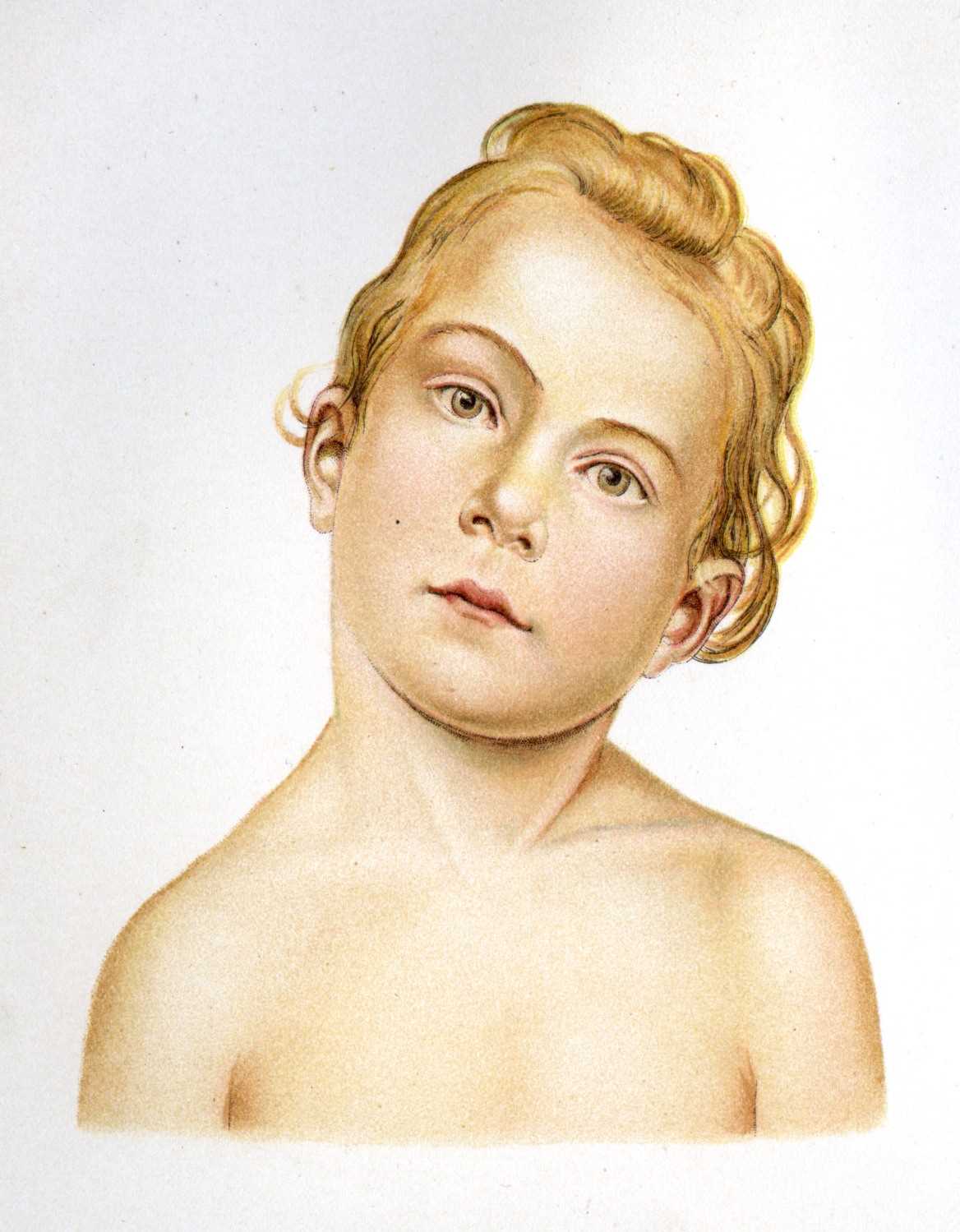

Due to unilateral muscle shortening, the child with congenital torticollis prefers to sleep in the prone position, with the affected side down. This position causes asymmetrical pressure on the skull and developing facial bones. This constant pressure on the head can lead to remodeling of the cheekbones and result in facial hemihypoplasia or plagiocephaly. These changes affect proper breastfeeding positioning, making it difficult for the baby to suckle during breastfeeding. Throughout the child's motor development, language, balance in different positions such as sitting, crawling originates compensations from disparate systems with possible consequences on orthostatic postures, such as scoliosis.

Evaluation

Physical examination is the easiest and most effective means of diagnosis. The most representative assessment methods for assessing congenital torticollis include an assessment of the passive cervical range of motion using an arthrodial goniometer (can be done by physical therapists), as well as an active range of motion, and global assessment. Neurological assessment, as well as auditory assessment, are fundamental to exclude other differential diagnoses.

It is crucial to assess visual function: eye alignment, presence of red reflex, and pupillary reaction to light, to determine whether it fixes and follows objects. Often there may be a weakness of the oculomotor muscles (lateral rectus or superior oblique); the torticollis results from a compensatory mechanism to improve vision. On physical examination, if there is no muscle contracture and joint amplitudes are intact, then this suspicion requires referral to ophthalmology.

The observed incidence of hip dysplasias is approximately 15% of patients with congenital torticollis; other studies report one in five babies has associated hip dysplasias. Multiple risk factors correlate with a higher incidence of hip dysplasia: female sex, first childbirth, family history of hip dysplasia, the existence of other deformities such as congenital torticollis, birth with a pelvic presentation, cesarean delivery, large fetus.

This condition can be bilateral and is most often unilateral. Early diagnosis of hip dysplasia is of utmost importance. It is an asymptomatic condition in the newborn, in which early detection can be effectively treated, improving the prognosis. Late diagnosis can result in sequelae such as lameness, chronic pain, degenerative arthritis, as well as mental impairment.

Thus, appropriate screening for this condition is essential for the clinical signs of hip dysplasia and the need for early diagnosis and, if in doubt, refer to a specialist. The clinical diagnosis systematically relies on both major and minor clinical signs. Major signs are Ortolani/Barlow sign and hip abduction limitation. The minor signs are Galeazzi sign and asymmetry of the folds (inguinal and thighs).[16]

The evaluation of congenital torticollis is very important for treatment planning.[2][17]

Clinical signs of congenital torticollis include:

- Fibrosis or shortening of the sternocleidomastoid muscle

- A lateral tilt of the head in the frontal plane and contralateral rotation in the transverse plane with notable limitation of the active and passive cervical range of motion.

- A palpable mass or tumor on the sternocleidomastoid during the first three months of life followed by restriction of range of motion and a fixed postural stiff neck resulting from a restricted or fixed muscle

- Modification of cranial morphology (related to the presence of plagiocephaly) by flattening the parieto-occipital zone and/or anteriorization of the contralateral ear to the affected sternocleidomastoid with frontal flattening homolateral to the affected sternocleidomastoid.[5]

- Compensatory postures of the cervical, thoracic, trunk, extremities, shoulder elevation, or trunk inclination to the affected side.

Diagnosis is usually made clinically, with few cases diagnosed through the use of complementary diagnostic tests. Diagnosis is generally before two months in 50% of cases; parents identify most cases and may correlate with plagiocephaly.

The most common imaging modality is ultrasonography, especially in the neonatal period. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be useful to rule out nonmuscular causes of torticollis.

Ultrasound is advantageous in assessing neck mass / pseudo-tumor, as well as long-term monitoring and post-treatment evaluation.

The swelling is firm, movable under the skin, and soft to the touch. The age of presentation varies with severity: postural is the version that appears earlier. The tumor tends to disappear between 4 and 8 months of age.[18][2][19]

Histopathologic studies are rarely necessary for instances where the imaging modalities are inconclusive regarding the etiology. In the early course of the condition, fine-needly aspiration cytology (FNAC) specimens are an option. Biopsy or surgical specimens have fewer findings since they are obtained in the latter course of the disease.

Regular hip examination and also ultrasound scan by 4 to 6 weeks of age or a plain radiograph of the hips (4 to 6 months of age) are a recommendation as at least 15 % of the infants have associated hip dysplasia.[2]

Treatment / Management

There are several ways to approach congenital torticollis, and there is no therapeutic standardization. Professionals in various fields, including physiotherapy and osteopathy, recommend techniques for the treatment of infant torticollis.[20]

With proper treatment, 90% to 95% of children improve before the first year of life, and 97% of patients improve if treatment starts before the first six months.[21][15][22]

With congenital torticollis, a palpable sternocleidomastoid mass is an important indicator for the intervention to be started by the second month of life, as it influences the child's normal motor development.[10]

The main goal is to achieve an age-appropriate active and passive range of motion of the neck and to prevent contractures and develop symmetry of face and head and neck.

Initial treatment focus on passive range stretching and close follow up. Parents are advised to perform positioning at schedules such as during feeds; this includes rotation of the chin towards the affected side shoulder. Infants can be placed on their stomach when awake and under supervision to develop motor skills in the prone position. Manual stretches such as flexion, extension, the lateral rotation should be done at least three times a week in a set of 15 stretches with each stretch for about a second with a 10 seconds pause in between. If there is a fibrous aspect, stretching techniques are the most essential and most evidence-based treatment.[2][7]

Although there are a large number of protocol studies in the literature demonstrating the effectiveness of physical therapy, there is little reported data on the frequency and types of exercise. In many studies, the initial frequency was 2 times per week in the 1st month, progressing to once per week; some authors refer 3 times a week initially. The duration of congenital torticollis physiotherapy treatment depends on the date on which rehabilitation began, and studies have shown that the sooner it starts, the faster the normal cervical biomechanics become established, as well as achieving better results. The published studies mostly have a basis in stretching/myotensive techniques and other motor development exercises.

Collar: Tubular orthosis for torticollis: It is used to support the impaired side of the neck in a neutral position. It is recommended for children more than four months of age, and the child can use it when they are awake during day time.[23]

Physical therapy is not always effective for treatment, and other resources may be used, such as the adjunctive use of botulinum toxin injection in the sternocleidomastoid other muscles in the region.[24] In other more severe cases, surgery is the last resort, but at all stages, physical therapy has its place in the follow-up.

Surgery: Surgical indications include cases where there is no improvement after six months of manual stretching if there are more than 15-degree defects in passive rotation and lateral bending, the presence of a tight muscular band, or a tumor in sternocleidomastoid. The procedure includes unipolar/ bipolar sternocleidomastoids muscle lengthening, "Z" lengthening, or radical resection of the sternocleidomastoid.[25][26]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis is essential to rule out other pathologies:

Vertebral anomalies like hemivertebrae and Klippel-Feil Syndrome;

Unilateral congenital absence of the SCM muscle;

- Congenital scoliosis

- Ocular torticollis

- Sandifer syndrome

- Arnold Chiari malformation

- Neurological diseases

- Visual disturbances

- Syringomyelia

- Cervical spine tumor

- Brain tumor

Fusion and segmentation osseous abnormalities often correlate with torticollis and other structural abnormalities. Radiology can differentiate these from torticollis.

There are also neurogenic causes, such as central nervous system tumors, ocular torticollis. Torticollis in these situations is due to underlying visual or neurologic problems other than sternocleidomastoid abnormalities. Here also, there is a normal neck examination with a full range of motion. To correct the torticollis underlying cause needs to be evaluated and treated.[8][19]

Prognosis

Most cases are benign and resolve spontaneously or with manual stretching. Craniofacial asymmetry is also improved, especially in early treated cases.

Complications

Permanent anatomic abnormalities can occur in scenarios where treatment gets delayed or is unavailable. It can be disfiguring and may have cosmetic concerns along with functional impairment.

Positional plagiocephaly is commonly associated with muscular torticollis, and it is essential to be able to differentiate a benign condition like positional plagiocephaly from craniosynostosis. A careful examination of the sutures as well as imaging, either a radiograph or an ultrasound might be necessary to differentiate one from the other. To manage plagiocephaly, the parents should be advised to do frequent positional changes which will halt remodeling of the skull. Referral to physical therapy to improve the neck motion are of utmost importance.

Craniofacial asymmetry is a long-term complication if the contracted sternocleidomastoid muscle is not released. Efforts should be made to correct torticollis to prevent the progression of facial asymmetry.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Congenital torticollis is best managed by an interprofessional team to avoid the high postural morbidity. The majority of patients are first identified by the parent who brings the infant or the child to the primary care provider. It is essential to identify congenital torticollis as early as possible to improve the outcome. Early diagnosis results in the initiation of prompt noninvasive correction, which prevents long-term disfiguring complications. Parents should receive education regarding the condition, their participation in its management, and prognosis of the condition. Healthcare providers should be aware of the relationship between congenital torticollis, its impact on the child's gross motor development and that most children resolve any motor delays associated with the condition by 3 to 5 years. A pediatric nurse should follow the child until there is a complete resolution of the congenital torticollis. With proper therapy from a collaborative interprofessional team, most children have a good outcome. [Level V]