Continuing Education Activity

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is a type of positive airway pressure that is used to deliver a set pressure to the airways that is maintained throughout the respiratory cycle, during both inspiration and expiration. The application of CPAP maintains PEEP, can decrease atelectasis, increases the surface area of the alveolus, improves V/Q matching, and hence, improves oxygenation. This activity describes the mechanism of action, indications, contraindications, and complications of CPAP therapy and explains the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with hypoxia that can benefit from CPAP therapy.

Objectives:

- Explain the mechanism of action of CPAP therapy.

- Describe the equipment, preparation, and technique in regards to the application of CPAP.

- Identify indications and contraindications for CPAP therapy and outline potential complications.

- Outline the role of an interprofessional team for improving care coordination and communication to effectively deliver CPAP therapy and improve outcomes.

Introduction

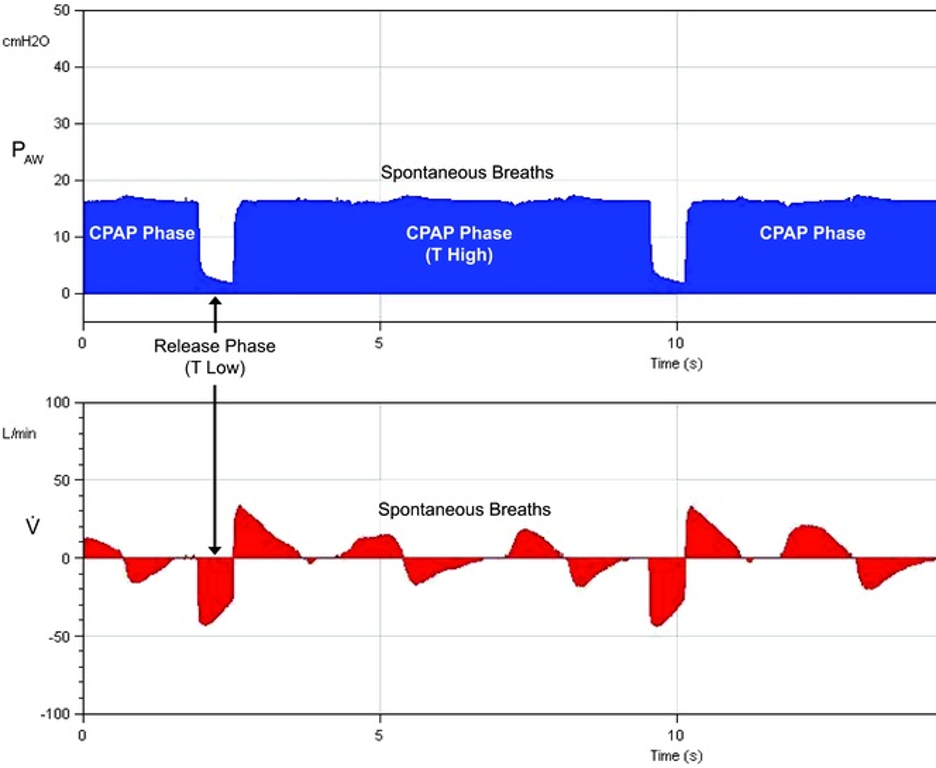

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is a type of positive airway pressure, where the air flow is introduced into the airways to maintain a continuous pressure to constantly stent the airways open, in people who are breathing spontaneously. Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is the pressure in the alveoli above atmospheric pressure at the end of expiration. CPAP is a way of delivering PEEP but also maintains the set pressure throughout the respiratory cycle, during both inspiration and expiration.[1] It is measured in centimeters of water pressure (cm H2O). CPAP differs from bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) where the pressure delivered differs based on whether the patient is inhaling or exhaling. These pressures are known as inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) and expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP). In CPAP no additional pressure above the set level is provided, and patients are required to initiate all of their breaths.

The application of CPAP maintains PEEP, can decrease atelectasis, increases the surface area of the alveolus, improves V/Q matching, and hence, improves oxygenation. It can also indirectly aid in ventilation, although CPAP alone is often inadequate for supporting ventilation, which requires additional pressure support during inspiration (IPAP on BiPAP) for non-invasive ventilation.

Anatomy and Physiology

Patients inhale air is inhaled through the nose, and the air travels through the nasopharynx, oropharynx, into the larynx, trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, and finally, to the alveoli. Sometimes, portions of the respiratory tract can be occluded by excess tissue, tonsillar overgrowth, the poor tone of the musculature, fatty excess, secretions among others. The forced air delivered by CPAP helps to keep the airways patent and prevents collapse.[2]

Indications

Airway collapse can occur from various causes, and CPAP is used to maintain airway patency in many of these instances. Airway collapse is typically seen in adults and children who have breathing problems such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which is a cessation or pause in breathing while asleep. OSA may arise from a variety of causes such as obesity, hypotonia, adenotonsillar hypertrophy, among others.[2]

CPAP may be used in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) to treat preterm infants whose lungs have not yet fully developed and who may have respiratory distress syndrome from surfactant deficiency.[3][4] Physicians may also use CPAP to treat hypoxia and decrease the work of breathing in infants with acute infectious processes such as bronchiolitis and pneumonia or for those with collapsible airways such as in tracheomalacia.

It is used in hypoxic respiratory failure associated with congestive heart failure in which it augments the cardiac output and improves V/Q matching.

CPAP can aid oxygenation via PEEP prior to placement of an artificial airway during endotracheal intubation.

It is used to successfully extubate patients that might still benefit from positive pressure but who may not need invasive ventilation, such as obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) or patients with congestive heart failure.

Contraindications

CPAP cannot be used in individuals who are not spontaneously breathing. Patients with poor respiratory drive need invasive ventilation or non-invasive ventilation with CPAP plus additional pressure support and a backup rate (BiPAP).

The following are relative contraindications for CPAP:

- Uncooperative or extremely anxious patient

- Reduced consciousness and inability to protect their airway

- Unstable cardiorespiratory status or respiratory arrest

- Trauma or burns involving the face

- Facial, esophageal, or gastric surgery

- Air leak syndrome (pneumothorax with bronchopleural fistula)

- Copious respiratory secretions

- Severe nausea with vomiting

- Severe air trapping diseases with hypercarbia asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Equipment

CPAP therapy utilizes machines specifically designed to deliver a flow of constant pressure.[5] Some CPAP machines have other features as well, such as heated humidifiers. Components of a CPAP machine include an interface for delivering CPAP.

CPAP can be administered in several ways based on the mask interface used:

- Nasal CPAP: Nasal prongs that fit directly into the nostrils or a small mask that fits over the nose

- Nasopharyngeal (NP) CPAP: Administered via a nasopharyngeal tube- an airway placed through the nose whose tip terminates in the nasopharynx. This has the advantage of bypassing the nasal cavity, and CPAP is delivered more distally.

- CPAP via face mask: A full face mask is placed over the nose and mouth with a good seal. It can be used for those that are mouth breathers, or for pre-oxygenation in spontaneously breathing patients prior to intubation.

A CPAP machine also includes straps to position the mask, a hose or tube that connects the mask to the machine’s motor, a motor that blows air into the tube, and an air filter to purify the air entering the nose.

Bubble CPAP is a mode of delivering CPAP used in neonates and infants where the pressure in the circuit is maintained by immersing the distal end of the expiratory tubing in water.[6] The depth of the tubing in water determines the pressure (CPAP) generated. Blended and humidified oxygen is delivered via nasal prongs or nasal masks and as the gas flows through the system, it “bubbles” out the expiratory tubing into the water, giving a characteristic sound. Pressures used are typically between 5 to 10 cm H2O. It requires skilled nurses and respiratory therapists to maintain effective and safe use of the bubble CPAP system.

For patients using CPAP in the outpatient setting at home, it is important to wear it regularly while asleep overnight and during daytime naps. Some CPAP units also come with a timed pressure “ramp” setting that starts the airflow at a low level and slowly raises the pressure to the set level that may make it more comfortable and easier to which to become accustomed.

Preparation

In an out of hospital setting, at first CPAP patients should be monitored in a sleep lab where the optimal pressure is often determined by a technologist manually titrating settings to minimize apnea. A sleep doctor or pulmonologist can help find the most comfortable mask, trial a humidifier chamber in the machine, or use a different CPAP machine that allows multiple or auto-adjusting pressure settings. Auto-titrating CPAP machines use computer algorithms and pressure transducer sensors to determine the ideal pressure to eliminate apneic events.

Complications

The first few nights on CPAP may be difficult, while patients acclimate. Many patients at first find the mask uncomfortable, claustrophobic or embarrassing.

Side effects of CPAP treatment may include congestion, runny nose, dry mouth, or nosebleeds; humidification can often help with these symptoms. Masks may cause irritation or redness of the skin, and use of the right size mask and padding can minimize pressure sores from tight contact with skin. The mask and tube must be kept clean, regularly inspected and should be replaced every 3 to 6 months. Abdominal distension or a sensation of bloating might occur which rarely can lead to nausea, vomiting and subsequently aspiration this can be minimized by decreasing the pressure or gastric decompression through a tube in hospitalized patients.

Compliance

In spite of several benefits of CPAP therapy, compliance remains a big problem both in the inpatient and outpatient setting.

Physicians should monitor for compliance and follow up with their patients closely especially during initiation of CPAP therapy to ensure long-term success.[7] Patients must disclose any adverse effects that may limit compliance which must then be addressed by the physician. Patients also need long-term follow up with an annual office visit to check equipment, titrate settings as needed, and to ensure ongoing mask and interface fit. Continuing patient education on the importance of regular use and support groups help patients obtain the maximum benefit of this therapy.

There may arise rare instances of respiratory distress where a hospitalized patient would greatly benefit from CPAP but does not tolerate the mask or is not complaint due to delirium, agitation or factors such as very young age in children or the elderly. In such scenarios, mild sedation with low dose fentanyl or dexmedetomidine can be used to improve compliance, until the therapy is no longer indicated. As the use of any sedative or anxiolytic agent can lead to decrease in consciousness and decrease in respiratory drive these patients should be monitored very closely. If adequate minute ventilation and or oxygenation cannot be achieved, then management should include escalation to BiPAP or intubation with mechanical ventilation following the code status and goals of care.

Clinical Significance

It is a commonly used mode of PEEP delivery in the hospital setting. It is also commonly used in the outpatient or home environment to treat sleep apnea.[8] Benefits of starting CPAP treatment include better sleep quality, reduction or elimination of snoring, and less daytime sleepiness. People report better concentration and memory and improved cognitive function. It can also improve pulmonary hypertension and lower blood pressure. CPAP can be used safely safe for all ages, including children.

CPAP helps in achieving better V/Q matching and ensures maintenance of functional residual capacity. CPAP is not associated with adverse effects of invasive mechanical ventilation like excessive use of sedation and side effects of positive pressure ventilation (volutrauma and barotrauma). In the inpatient setting, it should be monitored very closely with vital signs, blood gases, and clinical profile. If there is any sign of deterioration mechanical ventilation should be considered.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

CPAP is often prescribed by the primary care provider, nurse practitioner, internist and the neurologist for patients with obstructive sleep apnea. However, in order to have good compliance, patient education is vital. Many patients use these devices for a short time because of discomfort. CPAP is only a temporary treatment for obstructive sleep apnea and does not decrease the risk of cardiac complications. At the same time, patients should be encouraged to lose body weight, eat healthy, discontinue smoking and participate in regular exercise. [9]