Continuing Education Activity

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a wide-spread virus, with manifestations ranging from asymptomatic to severe end-organ dysfunction in immunocompromised patients with congenital CMV disease. Human cytomegalovirus is a member of the viral family known as herpesviruses, Herpesviridae, or human herpesvirus-5 (HHV-5). Human cytomegalovirus infections commonly are associated with the salivary glands. CMV infection may be asymptomatic in healthy people, but they can be life-threatening in an immunocompromised patient. This activity reviews the role of health professionals working together to manage cytomegalovirus.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of cytomegalovirus.

- Outline the presentation of cytomegalovirus.

- Summarize the treatment of cytomegalovirus.

- Review the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by cytomegalovirus.

Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a wide-spread virus, with manifestations ranging from asymptomatic to severe end-organ dysfunction in immunocompromised patients with congenital CMV disease. [1][2][3]

Human cytomegalovirus is a member of the viral family known as herpesviruses, Herpesviridae, or human herpesvirus-5 (HHV-5).

Human cytomegalovirus infections commonly are associated with the salivary glands. CMV infection may be asymptomatic in healthy people, but it can be life-threatening in an immunocompromised patient. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection can cause morbidity and even death. After infection, CMV often remains latent, but it can reactivate at any time. Eventually, it causes mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and it may be responsible for prostate cancer.

CMV infects between 60% to 70% of adults in industrialized countries and close to 100% in emerging countries. Of all herpes viruses, CMV harbors the largest number of genes dedicated to evading innate and adaptive immunity in the host. CMV represents a lifelong burden of antigenic T-cell surveillance and immune dysfunction. Congenital CMV is a leading infectious cause of deafness, learning disabilities, and intellectual disability.

Etiology

CMV is a double-stranded DNA virus and is a member of the herpesviruses. Like other herpesviruses, after recovery of the initial infection, CMV remains dormant within the host. Viral reactivation occurs during the compromise of the immune system with immunosuppression.

Epidemiology

Approximately 59% of the population older than six years old has been exposed to CMV, with an increase in the population’s seroprevalence with increasing age. Infection can occur as a primary infection, reinfection, or reactivation. Transmission of CMV can occur in numerous ways: via blood products (transfusions, organ transplantation), breastfeeding, viral shedding in close-contact settings, perinatally, and sexual transmission. Reactivation is seen in patients who become immunocompromised and is associated with elevated morbidity and mortality. [4][5]

- Primary infection: infection in seronegative patients; may be asymptomatic

- Recurrent infection: Reinfection or reactivation of CMV in seropositive patients

- CMV infection: Presence of CMV in body fluids (urine, blood) or tissue

- CMV disease: CMV infection with associated non-specific signs and symptoms and/or end-organ involvement

Pathophysiology

Once CMV is transmitted, and the primary infection clears, the virus remains dormant in myeloid cells. Vital replication and reactivation are contained primarily by cytotoxic T-cell immunity. However, when reactivation occurs, virions are released into the bloodstream and other body fluids, leading to the presence of symptoms, predominantly in immunocompromised patients.[6][7]

Histopathology

CMV replicates within endothelial cells at a slow rate. Like other herpesviruses, CMV expresses genes in a temporally controlled manner.

- Early genes within 0 to 4 hours after infection are involved in the regulation of transcription.

- Early genes within 4 to 48 hours after infection are involved in viral DNA replication and further transcriptional regulation.

- Late genes are expressed during the rest of infection up to viral egress and code for structural proteins.

- While CMV encodes for functional DNA polymerase, the virus makes use of the host RNA polymerase for the transcription of its genes.

Synthesis of the viral double-stranded DNA genome occurs in the host cell nucleus within specialized viral replication compartments.

History and Physical

Primary CMV infection usually has an asymptomatic or subclinical course. Mononucleosis is the most prevalent presentation of CMV in patients with an intact immune system, characterized by fever, rash, and leukocytosis. In the typical presentation of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) mononucleosis, the principal causal organisms include pharyngeal exudate and presence of heterophile antibodies, characteristics that are frequently absent in CMV mononucleosis.

Other manifestations include anemia, abnormal liver function tests, thrombocytopenia, positive rheumatoid factor, and positive antinuclear antibody levels. Organ involvement is uncommon in immunocompetent hosts. However, CMV is an important opportunistic pathogen in patients with a suppressed immune system, for example, from HIV, solid organ transplant, and bone marrow transplant. This can present with specific organ diseases, such as hepatitis, pneumonitis, and colitis.

In patients with a depressed immune system, CMV is more aggressive. Specific disease entities include:

- CMV hepatitis which may lead to fulminant liver failure

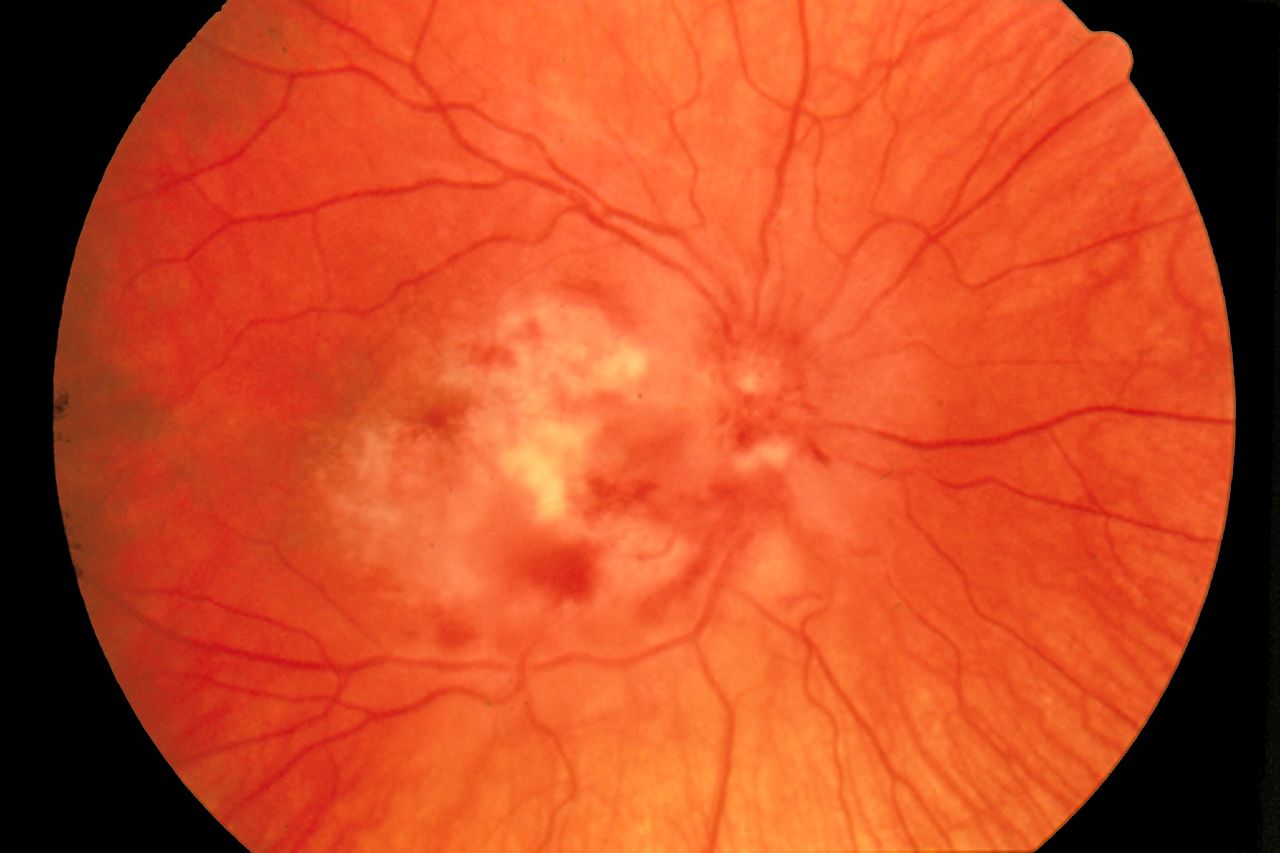

- Cytomegalovirus retinitis characterized by a "pizza pie appearance" on ophthalmic exam

- CMV esophagitis

- Cytomegalovirus colitis

- CMV pneumonitis

- Polyradiculopathy

- Transverse myelitis

- Subacute encephalitis

Evaluation

A definitive diagnosis is rarely required in immunocompetent patients. The diagnosis of CMV cannot be made solely based on clinical examination. Laboratory viral identification is the preferred initial test in patients who have suspected CMV infection. Although a histopathological diagnosis is a gold standard for diagnosis (by identification of CMV inclusion bodies), quantitative PCR assays are the preferred method for viral detection. In immunocompromised patients, the viral load can be undetectable in some cases. For this reason, a negative PCR does not exclude CMV infection. Serological testing provides essential information regarding serostatus before organ transplantation for risk-stratification of CMV infection. However, it is not recommended for the diagnosis of acute infection.[8][9]

Although the risks are low, CMV assays are part of the standard screening for non-directed blood donation in many countries. CMV-negative donations are earmarked for transfusion to infants or immunocompromised patients. Some blood donation centers maintain donor lists whose blood is CMV negative for special cases.

Testing for CMV resistance is now common in transplant centers. Resistance to ganciclovir has been noted in many transplant patients and makes treatment difficult. Resistance to CMV should be suspected in any transplant patient who fails to respond to therapeutic doses of ganciclovir or is rapidly declining in health.

Treatment / Management

Several antiviral agents have been approved for the treatment of CMV (cidofovir, foscarnet, ganciclovir, valganciclovir).[1][2][5]

- Immunocompetent patients present with minimal or no symptoms and are self-limited and do not require specific therapy other than symptomatic management. However, antiviral therapy should be considered in severe cases of CMV mononucleosis, CMV infection, and CMV disease in immunocompromised patients.

- The use of antiviral therapy is not without risk. Toxicity is common with the use of these agents and must be weighed against the benefits of initiating treatment.

Patients without CMV infection who receive organ transplants from CMV-infected donors should receive prophylactic treatment with valganciclovir or ganciclovir, and regular serological monitoring; if treated, the early establishment of a potentially life-threatening infection can be avoided.

Differential Diagnosis

- HIV

- Human Herpesvirus 6 infection

- Viral hepatitis

- Epstein Barr virus

- Infectious mononucleosis

Prognosis

The prognosis for most patients with CMV is good as long as they do not have a state of immunosuppression. Recovery is usually complete with treatment. However, fatigue may persist for several months.

CMV pneumonia in marrow transplant patients can carry high mortality if the treatment is delayed.

Complications

Relapse of CMV is very common in transplant patients

Deterrence and Patient Education

If the patient is about to undergo a transplant, one should discuss prophylaxis with ganciclovir.

Pearls and Other Issues

Antiviral Mechanisms of CMV Drugs

Anti-CMV drugs target the viral DNA polymerase, pUL54.

- Ganciclovir acts as a nucleoside analog. Its antiviral activity requires phosphorylation by the CMV protein kinase, pUL97.

- Cidofovir is a nucleotide analog, which is already phosphorylated and active.

- Foscarnet has a different mode of action as it directly inhibits polymerase function by blocking the pyrophosphate binding site of pUL54.

Two CMV proteins are implicated in the resistance of these drugs: pUL97 and pUL54.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

CMV can affect almost any organ in the body, and hence an interprofessional approach is necessary. Patients who are immunocompromised may be considered prophylaxis therapy. However, one also has to consider drug interactions and drug toxicity. Also, there is always the risk of developing drug resistance. A CMV vaccine is currently being evaluated in a clinical trial involving transplant patients, but it may be a few more years before it becomes available for routine use. Once an immunocompromised patient has been diagnosed with CMV, long-term follow up is necessary. Those who have retinitis need to follow up with an ophthalmologist.[10]

In the non-immunocompromised patient, CMV is rarely associated with mortality. However, in patients who are immunocompromised, receiving chemotherapy, or are using corticosteroids, CMV can have significant morbidity and mortality. After bone marrow transplants, mortality rates of 10-75% have been reported. For the healthy person who acquires CMV, recovery does occur, but it may take weeks or even months. Fatigue is a common residual complaint in most survivors. Overall, patients with comorbidity and immunosuppression have poor prognosis. Patients who develop CMV pneumonitis and require ventilation have an abysmal prognosis. [1][11]

The involvement of an interprofessional team can improve outcomes. Primary care providers, infectious disease specialists, transplant physicians, transplant nurses, and pharmacists can all be involved. Diagnosis and treatment are done by physicians and nurse practitioners. Pharmacists evaluate prescribed medications and check for interactions. Nurses monitor patients, educate them and their families, and update the team on changes in status. [Level V]