Continuing Education Activity

Dandy-Walker malformation or syndrome is a rare congenital neurological anomaly that affects the development of the cerebellum, the region of the brain responsible for motor coordination and balance. This posterior fossa anomaly is characterized by agenesis or hypoplasia of the vermis and cystic enlargement of the fourth ventricle, causing upward displacement of the tentorium and torcula. Most patients have hydrocephalus at the time of diagnosis. Dandy-Walker malformation is the most common posterior fossa malformation, and it typically occurs sporadically. The syndrome can manifest with a wide spectrum of neurological and developmental symptoms, making timely recognition and management crucial for improving patient outcomes. Treatment consists of treating the manifestations and associated comorbidities. This activity reviews the presentation of Dandy-Walker malformation and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of Dandy-Walker malformation.

Screen patients with suspected Dandy-Walker malformation efficiently, employing appropriate diagnostic tools and considering comorbidities.

Implement evidence-based treatment strategies for managing patients with Dandy-Walker malformation.

Collaborate with an interprofessional healthcare team to deliver comprehensive care and address the complex needs of patients with Dandy-Walker malformations.

Introduction

Dandy-Walker malformation (DWM) or syndrome is a posterior fossa anomaly characterized by:

- Agenesis or hypoplasia of the vermis

- Cystic enlargement of the fourth ventricle with communication to a large cystic dilated posterior fossa

- Upward displacement of tentorium and torcula (torcular-lambdoid inversion)

- Enlargement of the posterior fossa [1][2][3]

The first description of DWM dates back to 1887 by Sutton. Dandy and Blackfan described this deformity in 1914, and Taggart and Walker expanded on it in 1942. Bender first described the condition as DWM in 1954.[4]

The "Dandy-Walker complex" and "Dandy-Walker spectrum" are 2 of the most often used radiological entities proposed by Barkovich et al. in 1989.[5] Most patients have hydrocephalus at the time of diagnosis.[6] DWM is the most common posterior fossa malformation, and it typically occurs sporadically.[7]

Keeping the development of cerebellar vermis as the standard, the Dandy-Walker spectrum can be divided into:

- Dandy-Walker malformation

- Dandy-Walker variant

- Simple posterior fossa cistern widening

Dandy-Walker variant is characterized by cerebellar vermian hypoplasia, cystic fourth ventricular dilatation, and normal posterior fossa volume. This terminology is currently going out of favor as it generates a lot of confusion. Rather, individual physical abnormalities should be mentioned.[8]

Many patients remain clinically asymptomatic for years, while others may present with a variety of comorbidities leading to earlier diagnosis.[9] Treatment is generally focused on alleviating hydrocephalus and posterior fossa symptoms, often including surgical interventions like ventriculoperitoneal and cystoperitoneal shunting.[6][10]

Etiology

Historically, DWM was believed to be caused by atresia of the Luschka and Magendie foramina, leading to enlargement of the fourth ventricle and vermian hypoplasia. However, recent evidence suggests that DWM results from developmental abnormalities affecting the roof of the rhombencephalon, leading to variable degrees of vermian hypoplasia and cystic enlargement. This complex malformation may be initiated by 2 different pathophysiological mechanisms: the arrest of vermian development and the failure of fourth ventricle foramina fenestration, leading to an enlarged Blake’s pouch and causing compression of the vermis.[11]

DWM may be isolated or associated with chromosomal abnormalities, Mendelian disorders, syndromic malformations, congenital infections, and various other comorbidities.[11] Central nervous system (CNS) disorders related to DWM include malformations of cortical development, holoprosencephaly, dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, and neural tube defects.[3]

Rare mutations have been described in some genes including FOXC1 (in locus 6p25.3), ZIC1, and ZIC4 (in locus 3q24), FGF17, LAMC1, and NID1.[7]

Epidemiology

DWM and related variants have a prevalence of 1 in 350,000 live births in the United States. These malformations account for approximately 1% to 4% of hydrocephalus cases.[1][3] Most DWM patients present with signs and symptoms from increased intracranial pressure, most commonly related to hydrocephalus and the posterior fossa cyst. For this reason, therapy generally aims to control intracranial pressure, usually through surgery.

Some institutions have an estimated mortality rate of 12% to 50%.[1] Treatment of hydrocephalus with shunting substantially improves mortality.[12] Fetal mortality directly correlates with the presence of extra-CNS abnormalities.[13]

Pathophysiology

The majority of cases are sporadic. However, some may result from chromosomal aneuploidy, Mendelian disorders, and environmental exposures, including congenital rubella and fetal alcohol exposure. This condition underscores the intricate interplay between genetic and environmental factors in brain development.[9]

Several conditions have been reported to be associated with DWM:

- Mendelian disorders:

- Warburg syndrome

- Coffin-Siris syndrome

- Fraser cryptophthalmos

- Joubert–Boltshauser syndrome

- Meckel–Gruber syndrome

- Aicardi syndrome

- Neurofibromatosis type 1[14]

- Chromosomal aberrations:

- Duplication syndromes, including those involving 5q; 8p; 8q; 17q

- Trisomies 9, 13, and 18

- Triploidy

- Deletion at 6(p24–p25)

- 9ph+ heteromorphism

- Environmental agents:

- Prenatal exposure to rubella, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, coumadin, alcohol

- Maternal diabetes

- Sporadic syndromes:

- Klippel–Feil syndrome

- Goldenhar syndrome

- Cornelia de Lange syndrome

Concept of the Midline as a Developmental Field (Opitz and Gilbert)

An insult to this field can result in pleiotropic sequelae on midline structures- the central nervous system (CNS), heart, palate, midface, vertebrae, genitalia, and sacrococcygeal region. DWM should be considered a complex developmental disturbance of the midline of marked genetic and etiological heterogeneity.

Embryology

The cerebellar vermis develops from top to bottom at 17 to 18 weeks gestation.[15] Due to vermian developmental arrest or compression of the vermis brought on by a failure of fourth ventricle foramina fenestration and consequent growing of Blake's pouch, the roof of the rhombencephalon does not form correctly.

History and Physical

The clinical presentation is nonspecific, subject to multiple factors, including the severity of hydrocephalus, intracranial hypertension, and associated comorbidities.[1] Most patients will present in their first year of life with signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure.[6][7][12] The most common manifestation is macrocephaly, affecting 90% to 100% of patients during their first months of life.[7] The syndromic form of DWM may also have malformations of the heart, face, limbs, and gastrointestinal or genitourinary system that could draw initial medical attention.[9] Almost 75% of cases will have hydrocephalus by the age of 3 months, and eventually, almost 90% of the patients will have hydrocephalus.

A case series of 42 patients with DWM showed hydrocephaly in all patients at the time of diagnosis, vermian hypoplasia in 88%, and cerebellar hypoplasia in 59%.[6]

Evaluation

Ultrasound is typically the first imaging modality in assessing the fetal brain. CNS structures evaluated through this modality should include head size and shape, choroid plexus, thalami, cerebellum, cavum septum pellucidum, lateral ventricles, nuchal fold, cisterna magna, and spine. Imaging may also demonstrate other CNS abnormalities that commonly correlate with DWM.

Measurement of the cisterna magna forms part of the ultrasound evaluation of the fetal brain. A case series showed an upper limit of normal of 10 mm and a mean size of 5 plus or minus 3 mm at 15 or more gestational weeks. A prominent cisterna magna during prenatal fetal ultrasound evaluation may raise concern for congenital posterior fossa abnormalities. However, as an isolated finding, a prominent cisterna magna is unlikely to be clinically significant if the patient presents no other abnormalities.[16]

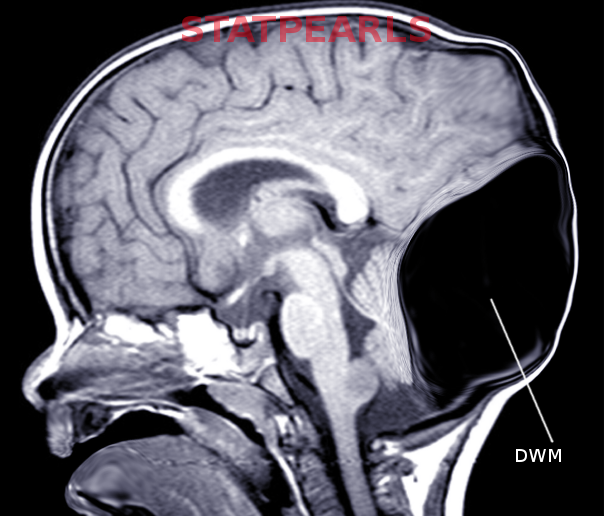

Radiological Criteria for Diagnosis

The classical radiological triad of DWM includes hypoplastic vermis, fourth ventricle enlargement, and torcular elevation.[17]

However, Klein et al. modified the classification by Barkovich et al. in 2003 to identify the radiological criteria for the diagnosis of DWM:

- Large, median posterior fossa cyst widely communicating with the fourth ventricle (see Image. Occipital Meningocele With Dandy-Walker Cyst)

- Absence of the lower portion of the vermis at different degrees (lower 3/4, lower half, lower 1/4)

- Hypoplasia, anterior rotation, and upward displacement of the remnant of the vermis

- Absence or flattening of the angle of the fastigium

- Large bossing posterior fossa with an elevation of the torcula

- Anterolateral displacement of normal or hypoplastic cerebellar hemispheres [18]

Like ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more helpful after the 20th week of gestation, and it may aid in evaluating CNS malformations not satisfactorily described by ultrasound and search for commonly associated abnormalities.[3][19][20]

Prenatal diagnosis by ultrasound is possible after the 18th week of gestation when the cerebellar vermis has completely developed. Diagnosis may be confirmed by magnetic resonance.[19][21] For patients with the Dandy-Walker variant (DWV), discrepancies may be found in prenatal and postnatal imaging based on the variation of vermian development.[20] Magnetic resonance will also help distinguish DWM from other posterior fossa lesions (see Image. Dandy-Walker Malformation).[3]

Karyotype and postnatal imaging should be offered for all patients with prenatal imaging findings consistent with DWM to confirm findings and search for other possibly associated abnormalities.[13][20]

Measurement of the brainstem-vermian (BV) angle and brainstem-tentorium (BT) angle substantially help in the differential diagnosis of patients with an increased size of the cisterna magna. The BV angle increases with the severity of the condition. Angles <18 degrees are normal, while 18 to 30 degrees suggest Blake's pouch malformation. The BT angle ranges typically between 21 to 44 degrees. Both angles >45 degrees are strongly suggestive of DWM.[22]

Associated CNS abnormalities include occipital encephalocele, polymicrogyria, agenesis, or dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, and heterotopia.

Treatment / Management

Treatment consists of treating the manifestations and associated comorbidities. Most patients present with signs and symptoms from increased intracranial pressure, most commonly related to hydrocephalus and posterior fossa cyst. For this reason, therapy generally aims to control intracranial pressure, usually through surgery.[3]

Surgical treatment may include ventriculoperitoneal (VP) or cystoperitoneal (CP) shunts. Other patients may be candidates for endoscopic procedures, including endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV).[23]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes posterior fossa abnormalities that may be associated with hydrocephalus sometimes, which commonly may present in a similar way to DWM; these include retrocerebellar arachnoid cysts, cystic hygroma, Blake's pouch cyst, mega cisterna magna, and vermian hypoplasia. Additionally, several syndromes correlate with DWM, such as Aase-Smith, cerebro-oculo-muscular syndrome, Coffin-Siris, Cornelia de Lange, and Aicardi.[3][9]

The other cystic malformations of the posterior fossa include persistent Blake's pouch, mega cisterna magna, and arachnoid cyst.

The non-cystic malformations include Joubert syndrome, rhombencephalosynapsis, tectocerebellar dysraphia, and neocerebellar dysgenesis.[5]

Retrocerebellar arachnoid cysts may be large enough to cause compression of cerebellar hemispheres and the fourth ventricle.[3]

Blake's cyst is a retrocerebellar fluid collection with a medial line communication to the fourth ventricle.[3]

Mega cisterna manga refers to a fluid collection located posteroinferior to a normally developed cerebellum.[3]

Several comorbidities may also correlate with DWM, including syndromic and non-syndromic, CNS and non-CNS anomalies, chromosomal abnormalities, cardiovascular conditions, mental illness, and severe intellectual disability.[9]

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with DWM is highly variable and dependent on several factors, including the severity of the malformation, the timeliness of diagnosis and intervention, and the presence of associated complications. In milder cases, where the cerebellar vermis is less affected and with minimal intracranial pressure, individuals may experience fewer neurological deficits and lead relatively normal lives with appropriate management and support. However, in more severe cases with significant cerebellar and posterior fossa abnormalities, patients are at a higher risk of experiencing developmental delays, intellectual disabilities, motor coordination issues, and hydrocephalus.

Fifty percent of children with untreated hydrocephalus die before age 3, and only approximately 20% to 23% will reach adult life. Most of the patients with untreated hydrocephalus who reach adult life will have motor, visual, and auditory deficits.[24]

The diameter of the fetal lateral ventricle measured by obstetric ultrasound may have substantial prognostic value. As described in a previous study, lateral ventricles measuring between 11 mm to 15 mm correlate with a 21% risk of developmental delay. If the diameter measures >15 mm, the risk of developmental delay is above 50%.[25]

Most case series of patients with nontumoral hydrocephalus present an overall risk for epilepsy of approximately 30%.[24]

Functional outcome is subject to several factors, which include other structural brain abnormalities, extra-CNS manifestations, epilepsy, motor, visual, or hearing impairment, and other congenital abnormalities.[26][27]

Complications

Complications in DWM can encompass a broad spectrum of neurological and developmental challenges. One of the primary complications is hydrocephalus, leading to increased intracranial pressure. This increased pressure can lead to symptoms such as headaches, vomiting, and cognitive impairments, making timely intervention essential. The most common complications associated with shunting are infection and shunt malfunction.[12]

Patients with DWM may experience various motor and coordination deficits due to the cerebellar abnormalities, affecting their daily functioning and quality of life. Cognitive and intellectual disabilities, speech and language impairments, and behavioral problems are common as well, adding to the complexity of managing this condition. Furthermore, the associated structural anomalies may result in additional complications, including the risk of syringomyelia or other spinal cord abnormalities.

Sixteen percent of patients with isolated DWM have chromosomal abnormalities.[28] DWM may be associated with malformations of the face, limbs, heart, and genitourinary or gastrointestinal system.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The cerebellar vermis development varies between individuals and usually completes its formation late in the first half of pregnancy. Some fetuses may achieve vermis development around gestational week 18. Therefore, the diagnosis of DWM based on imaging performed before weeks 16 to 18 of development may be premature and erroneous. Additionally, the cisterna magna has not reached its final anatomy during the first half of pregnancy. A relatively wide opening in the cerebellomedullary cistern may not indicate vermian dysgenesis at that stage of development. Therefore, the cerebellum should be reevaluated at 20 to 22 weeks gestation to rule out vermian abnormalities.[29]

Karyotype and comprehensive fetal ultrasound should be offered for patients with features of the Dandy-Walker complex.[20]

In the absence of other lesions in the posterior fossa, an isolated prominent cisterna magna may not be clinically significant.[16]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In managing patients with DWM, a multidisciplinary healthcare team comprised of physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals plays a pivotal role in enhancing patient-centered care, outcomes, patient safety, and team performance. Pediatric healthcare providers should be familiar with the broad spectrum of congenital posterior fossa abnormalities to provide an accurate diagnosis, optimal therapy, and genetic counseling.[29] Additionally, posterior fossa imaging findings will change based on the gestational age; as such, findings suggestive of disease in earlier weeks should be reevaluated at weeks 20 to 22 gestation.[16]

Skillful expertise, honed through continuous education and training, is essential for correctly diagnosing and treating this complex neurological condition. A well-structured strategy involving the collaboration of various professionals ensures that each aspect of the patient's care plan is addressed comprehensively. Timely consultation should be obtained from the pediatric neurosurgeon/neurologist.

Ethical considerations, such as informed consent and respect for patient autonomy, guide decision-making and promote trust within the interprofessional team. Responsibilities are distributed efficiently, with clear roles and accountabilities to optimize patient care. Effective interprofessional communication fosters the exchange of critical information and the seamless coordination of care, helping to minimize errors and improve patient safety. Care coordination, facilitated by healthcare professionals, enables a holistic approach to patient management, offering the best chance for positive outcomes in the challenging realm of DWM.