Continuing Education Activity

Pressure ulcers are skin or soft tissue injuries that form due to prolonged pressure exerted over specific areas of the body. They should receive prompt treatment; otherwise, complications associated with these injuries can be fatal. The cornerstone of treatment is to reduce the pressure exerted at the site of the lesion. Treatment options vary according to the stage/grade of the pressure ulcer. This activity involves the etiology, pathophysiology, and histopathology of the pressure ulcers, as well as highlighting evaluation and treatment options based on an interprofessional approach, so that patient care and outcomes are optimal.

Objectives:

- Describe different etiological factors that cause pressure ulcers.

- Identify various medical conditions that lead to pressure ulcers. Explain complications that result from these ulcers.

- Outline treatment options based on grade and complication of pressure ulcer.

- Explain the importance of coordination and communication amongst the interprofessional team to enhance optimum patient care and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Decubitus ulcers, also termed bedsores or pressure ulcers, are skin and soft tissue injuries that form as a result of constant or prolonged pressure exerted on the skin. These ulcers occur at bony areas of the body such as the ischium, greater trochanter, sacrum, heel, malleolus (lateral than medial), and occiput. These lesions mostly occur in people with conditions that decrease their mobility making postural change difficult. Jean-Martin Charcot was a French doctor in the 19th century who studied many diseases, including decubitus ulcers. He noticed that patients who developed eschar of the buttocks and sacrum died after some time. He named this lesion "decubitus ominous," which meant death was inevitable after developing this lesion.[1]

Etiology

The development of decubitus ulcers is complex and multifactorial. Loss of sensory perception, locally and general impaired loss of consciousness, along with decreased mobility, are the most important causes that aid in the formation of these ulcers because patients are not aware of discomfort and hence do not relieve the pressure.[2] Both external and internal factors work simultaneously, forming these ulcers. External factors; pressure, friction, shear force, moisture, and internal factors; fever, malnutrition, anemia, and endothelial dysfunction speed up the process of these lesions.[3]

Immobility of as little as two hours in a bedridden patient or patient undergoing surgery is sufficient to create the basis of a decubitus ulcer.[3]

The dysfunction of nervous regulatory mechanisms responsible for the regulation of local blood flow is somewhat culpable in the formation of these ulcers.[4] Prolonged pressure on tissues can cause capillary bed occlusion and, thus, low oxygen levels in the area. Over time, the ischemic tissue begins to accumulate toxic metabolites. Subsequently, tissue ulceration and necrosis occur.

Patients with the following conditions exhibit a predisposition to decubitus ulcers:

- Neurologic disease

- Cardiovascular disease

- Prolonged anesthesia

- Dehydration

- Malnutrition

- Hypotension

- Surgical patients

Epidemiology

Decubitus ulcers are a significant health care problem worldwide, which affects several thousand people each year.[3] Their management costs billions of dollars per annum, burdening the already scarce health economy.

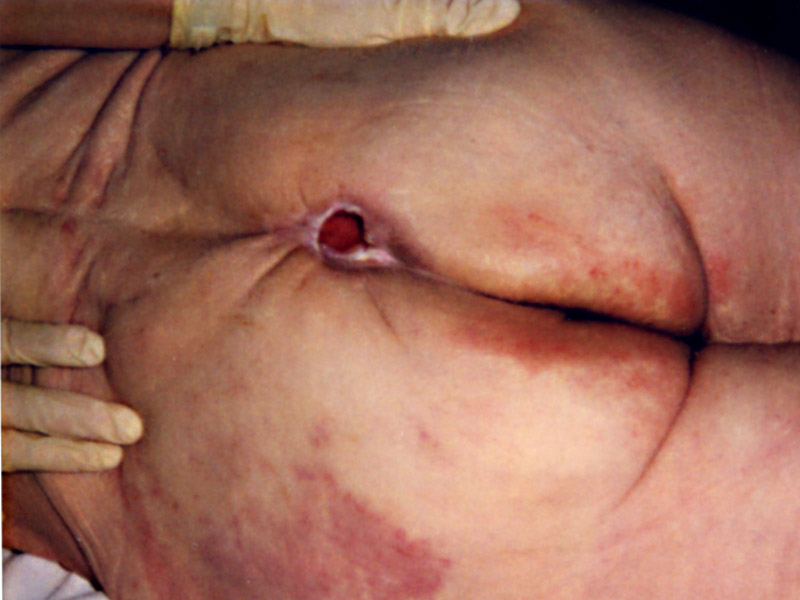

Sacral decubitus ulcers usually occur in elderly patients. Patients who are incontinent, paralyzed, or debilitated are more prone to getting them. Patients with normal sensory status, mobility, and mental status are less likely to form these ulcers because their normal physiologic feedback system leads to frequent physical positional shifts. As stated above, elderly patients are more prone to sacral decubitus ulcers; two-thirds of ulcers occur in patients who are over 70 years old. There is data that shows 83% of hospitalized patients with ulcers developed them within five days of their hospitalization.[3]

A study done in a medical research center in Turkey concluded that 360 patients out of 22834 admitted patients developed one or more pressure ulcers. Most of the patients who developed pressure ulcers were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).[5]

Pathophysiology

Decubitus ulcer formation is multifactorial (external and internal factors), but all of these result in a common pathway leading to ischemia and necrosis. Tissues can sustain an abnormal amount of external pressure, but constant pressure exerted over a prolonged period is the main culprit. External pressure must exceed the arterial capillary pressure (32 mmHg) to impede blood flow and must be greater than the venous capillary closing pressure (8 to 12 mmHg) to impair the return of venous blood. If the pressure above these values is maintained, it causes tissue ischemia and further results in tissue necrosis.[6] This enormous pressure can be exerted due to compression by a hard mattress, railings of hospital beds, or any hard surface with which the patient is in contact.

Friction caused by skin rubbing against surfaces like clothing or bedding can also lead to the development of ulcers by contributing to breaks in the superficial layers of the skin. Moisture can cause ulcers and worsen existing ulcers via tissue breakdown and maceration.

Histopathology

Histological studies of the decubitus ulcer extent, which include blanch able erythema, non-blanch able erythema, decubitus dermatitis, decubitus ulcer, and black scab/gangrene, show a dynamic process. The initial change occurs in the vessels of the papillary dermis. After this follows the necrosis of skin structures. The scab/gangrene is a full-thickness defect that is due to either persistent ischemia and anoxemia or a sudden occlusion of large vessels due to shear injury.[7]

Detailed analysis of chronic pressure ulcers showed the presence of densely aggregated bacterial colonies, often present in the extracellular matrix, but these findings were not present in acutely developed ulcers.[8]

History and Physical

In most instances, decubitus ulcers are reported by a patient’s attendant. This is because the lack of sensation at the site of the lesion makes the patient unaware of his injury. There might be staining of the patient’s clothes or bedsheets due to pus or blood discharge. The clinical presentation may vary between different sites of the body as skin, soft tissue, and muscle resist differently to external pressure. The muscle becomes ischemic and necrotic before skin breakdown can occur, which can be deceiving to the clinician’s observation undermining the depth or extent of the ulcer.

The following require examination in a patient with a decubitus ulcer:

- Ulcer history, including etiology, duration, and previous treatment (if any)

- Staging by thoroughly examining the depth of the wound, which this activity will cover in detail under "staging."

- Size (length, width)

- Sinus tracts, undermining, and tunneling

- The presence of drainage

- The presence of necrotic tissue

A detailed discussion of the history and associated conditions follows under "evaluation."

Evaluation

The initial evaluation of patients with pressure injuries involves a detailed history, and the clinician should gather the following:

- Duration of immobility or being bedridden

- Duration of hospital stay

- Associated medical cause that has caused the injury (e.g., paraplegia, quadriplegia, stroke, road traffic accident (RTA) that might have resulted in immobility

- The natural history of the injury; the site at which it first developed. Did it increase in size? How long has the injury been present?

- A brief history of any systemic diseases is also necessary. Diseases like diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, and malignancy prevent or slow down wound healing.

- If the patient can precisely localize the site of the ulcer or localize any associated pain because most of the time, the ulcers are painful, but the patient is unaware because either he has paraplegia or is in a critical condition.

- Is there any discharge or foul odor from the ulcer site? These may specify the worsening of the lesions.

Treatment / Management

Managing decubitus ulcers is complicated as there is no fixed treatment regime or algorithm. Once it has developed, there should be no delay in treatment, and management should start immediately.[9] Treatment varies between site, stage, and associated complications of the ulcer. The goal of all the various treatment options is to; minimize the pressure exerted on the ulcer, minimize contact of the ulcer with a hard surface, decrease moisture, and to keep it as aseptic or least septic as possible. The choice of treatment options should be according to the stage/grade of the ulcer, and what the purpose of the treatment should be (decreasing moisture, removal of necrotic tissue, controlling bacteremia).

Prevention is clearly the best treatment with excellent skincare, pressure dispersion cushions, and support surfaces. Support surfaces decrease the amount of pressure on the wound. Support surfaces can be either static (e.g., air, foam, and water mattress overlays) or dynamic (e.g., alternating air overlay). Repositioning and turning the patient every two hours can also lessen pressure on the area, but some patients may require more frequent repositioning, while others may require less frequent repositioning.[10]

In some cases, urinary and fecal diversion may be necessary depending on the site of the ulcer, being prone to urine or fecal contamination.

Hydrocolloid dressings should be used. Good antibiotic cover decreases septicemia.

The depth and severity of the ulcer determine whether surgical management may be required. The ulcer must be thoroughly cleaned and drained to remove any dead tissue and debris. Vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) may be a preoperative option to provide a favorable wound for the surgical closer.[11] Surgical management aims to fill the dead space and provide durable skin through flap reconstruction.

There is also some evidence to suggest that hyperbaric oxygen therapy can help with wound healing, as it improves oxygenation in and around the area of the wound.[12]

Thus, the treatment of decubitus ulcers has its basis on the following:

- Prevention of additional ulcers

- Decreasing pressure on the wound

- Wound management

- Surgical intervention

- Improving the nutritional status

For the most part, stage I and II ulcers do not require operative measures. Stage 3 and 4 ulcers may require surgical intervention.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of sacral decubitus ulcers include[2]:

- Diabetic ulcers

- Venous ulcers

- Pyoderma gangrenosum

- Osteomyelitis

Staging

There are many different ways to stage sacral decubitus ulcers. The most widely accepted classification system is the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) system.[3] It uses ulcer depth as a way to classify these ulcers.

The stages are as follows:

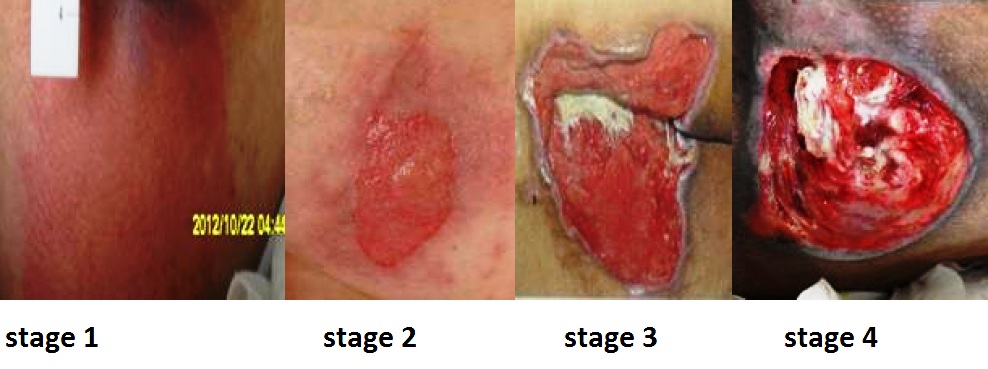

- Stage I: The skin is intact with the presence of non-blanchable erythema.

- Stage II: There is partial-thickness skin loss involving the epidermis and dermis.

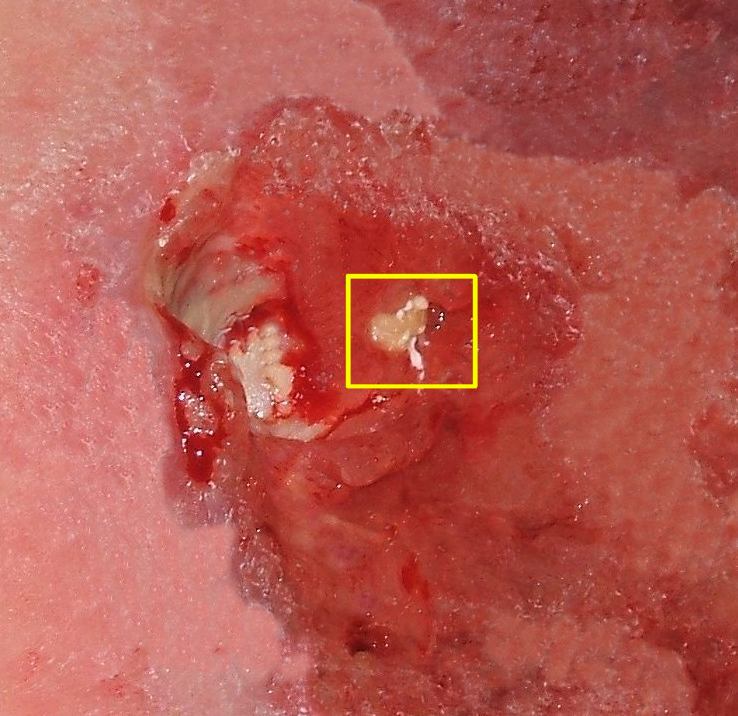

- Stage III: There is a full-thickness loss of skin that extends to the subcutaneous tissue but does not cross the fascia beneath it. The lesion may be foul-smelling.

- Stage IV: There is full-thickness skin loss extending through the fascia with considerable tissue loss. There might be possible involvement of the muscle, bone, tendon, or joint.

Prognosis

There have been many studies researching the prognosis and outcomes for patients with sacral decubitus ulcers, but given the different treatment regimens, the prognosis varies. One showed that 53% of pressure ulcers healed within 42 days when "sheng-ji-san"-a Chinese herbal medicine, was used as a dressing.[13] Another study showed that no ulcer ever healed completely.[14]

Although outcomes have been difficult to study, there is general agreement that most of the time, lifelong treatment and prevention measures are necessary for these patients. Patients with sacral decubitus ulcers are at high risk of recurrence.[15]

Complications

Complications often develop with decubitus ulcers. The most common problem is infection. Grade III and IV ulcers require management intensively as their complications can be life-threatening. Microbial analysis has shown that both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria are present in the lesions.[16] If the infection spreads to deeper tissues and the bone it can result in; periostitis (infection of the layer covering the bone), osteomyelitis (infection of a bone), septic arthritis (infection of a joint), and formation of sinuses (abnormal cavity formed by loss of tissue). The invasion of the infective agent results in fatal consequences because septicemia is challenging to manage in an already debilitated patient.

These wounds are catabolic (meaning that they use up a lot of energy). The catabolic nature of these ulcers causes severe fluid and protein loss, which can result in hypoproteinemia or malnutrition. Up to 50 grams of body protein can be lost daily due to a draining ulcer.[16]

Chronic decubitus ulcers can cause chronic anemia or secondary amyloidosis. Anemia also occurs secondary to chronic water loss and bleeding.[16]

If there is inadequate postoperative care complications secondary to reconstructive surgery can occur. These include hematoma or seroma formation, wound dehiscence, abscess formation, or postoperative wound sepsis.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative care of patients who have undergone reconstructive surgery is of utmost significance as these ulcers have high rates of recurrence. A study done on characteristics of recurrent pressure ulcers showed that patients who underwent reconstructive surgery and developed post-operative, had an 11% to 19% chance of recurrence. Those without any postoperative complications had recurrence as high as 61%.[17]

When medical staff shift patients from the operating table to their air-fluid beds, they must avoid excessive shearing, and stretch on skin flaps. For the first four weeks, patients are positioned flat on their support surfaces, after which they can place themselves in a semi-sitting position. The patient starts to sit for 10 minutes only after six weeks of the surgical procedure. After these sitting periods, the flap should be examined for discoloration and wound edge separation. Over two weeks, the sitting periods will increase to 2 hours in 10-minute increments. Patients will also learn to lift for 10 seconds every 10 minutes to relieve pressure. Meticulous skin care is necessary.

Consultations

Managing decubitus ulcers should always be done with an interprofessional approach. Usually, a general surgery consultation is necessary for patients with sacral decubitus ulcers, especially for those with deep ulcers. A wound care specialist or a dermatologist is involved in non-healing ulcers. If any associated medical conditions affect the wound healing process, an internal medicine specialist should have involvement in the management of the case. Patients who have contractures or have spastic paralysis have regular physiotherapies.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients and their family members should have a clear idea that preventing recurrence requires commitment and responsibility. They should receive education on how to manage their condition in the hospital and as well as in their homes. They should be familiar with warning signs like skin discoloration, ulceration, discharge, or a foul smell from the ulcer site and body areas with decreased or no sensation.

The patient should move or turn every 2 hours; it could not be done by themselves, or they should ask someone to help them. Air or water mattress should be used in their homes too. Their food intake should be adequate and should consist of a balanced and healthy diet. Active mattress use leads to significant improvements in resting blood flow, post-occlusive reactive hyperemia, and baseline skin temperature. These results suggest that active mattress use can improve endothelial function.[18]

Pearls and Other Issues

Decubitus ulcers occur when there is prolonged pressure on specific areas of the body that are susceptible to friction and shear force injuries. Pressure ulcers vary in size, depth, and chronicity. There is a grading system in place for pressure ulcers, which helps guide treatment. Consulting with a wound care specialist and/or general surgery can also help guide treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The main goal is to prevent a decubitus ulcer by decreasing the pressure acting on the affected site. This goal requires an interprofessional team, including primary care providers, wound care specialists, surgeons, specialty-trained wound nurses, physical therapists, and nurses aides. Nurses provide care, monitor patients, and notify the team of issues. Nurses aides are often responsible for turning and repositioning patients. [Level 5] Air-fluidized or foam mattresses should be used, frequent postural changes, provision of adequate nutrition, and treatment of any underlying systemic illnesses. Debridement should take place to remove dead tissue that serves as the optimum medium for the growth of bacteria. Hydrogels or hydrocolloid dressing should be used, which aid in wound healing.[19] Tissue cultures are necessary, so the most directed antibiotic can be administered, which can involve the pharmacist and the latest antibiogram data. The patient should be kept pain-free by giving analgesics. They should try to increase physical activity if possible, which a nurse's aide, medical assistant, or rehab nurse can facilitate. Frequent follow-ups are an absolute necessity and a team approach to patient education and management involving the wound care nurse and wound care clinician will lead to the best results. These interprofessional activities can help drive better outcomes for patients with decubitus ulcers. [Level 5]

Each year around 60000 patients die due to complications of decubitus ulcers.[19] Therefore patients with these injuries should get prompt treatment, as worsening of this condition increases the risk of mortality and increased healthcare costs.