Continuing Education Activity

Diaphragmatic injuries are relatively uncommon, representing less than 1% of traumatic injuries. They are typically considered a marker of severe trauma due to the high rate of associated injury. While large diaphragmatic injuries may be clinically obvious in the acute setting, diaphragmatic injuries are often occult, and a high index of suspicion must be maintained to prevent missing this important diagnosis. A missed diaphragmatic injury may result in delayed herniation and strangulation of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity through the unrepaired defect in the diaphragm. A thorough knowledge of the anatomy, associated injuries, and pitfalls in diagnostic testing will assist in diagnosing this surgical condition. This activity reviews the workup of diaphragm rupture and describes the role of health professionals working together to managing this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the presentation of a patient with diaphragmatic rupture.

- Outline the treatment of diaphragmatic rupture.

- Describe the surgical approach to diaphragmatic rupture.

- Summarize the role of health professionals working together as an interprofessional team in managing this condition.

Introduction

The diaphragm is the arched, flat muscular structure that divides the thorax from the abdominal cavity. Diaphragmatic injuries are relatively uncommon, representing less than 1% of traumatic injuries. They are typically considered a marker of severe trauma due to the high rate of associated injury. Certain injury patterns increase the risk of diaphragmatic injury, and penetrating trauma is a more common mechanism than blunt trauma. While large diaphragmatic injuries may be clinically obvious in the acute setting, diaphragmatic injuries are often occult, and a high index of suspicion must be maintained to prevent missing this important diagnosis. A missed diaphragmatic injury may result in delayed herniation and strangulation of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity through the unrepaired defect in the diaphragm. A thorough understanding of the anatomy, associated injuries, and pitfalls in diagnostic testing will assist in diagnosing this surgical condition.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Injury to the diaphragm may be due to penetrating or blunt trauma. Penetrating trauma with direct injury to the diaphragm is more common and accounts for about two-thirds of cases. Stab wounds are the most frequent etiology, followed by gunshot wounds and impalements. Penetrating trauma usually results in smaller, unilateral injuries, which are more likely to be missed in the initial evaluation. The remaining one-third is due to blunt trauma with the vast majority (90%) caused by motor vehicle crashes. Falls and crush injuries account for the remainder. Blunt trauma causes larger ruptures; up to one-third of these ruptures may be bilateral.

Epidemiology

Like most traumatic conditions, the diaphragmatic injury is more common in males. Patients with blunt injuries tend to be older with a median age of 44 years. In contrast, those with penetrating injuries have a median age of 31 years. Patients with blunt injury also have higher injury severity scores (33 versus 24). More than 50% of patients with diaphragmatic injury will have significant associated injuries. Mortality varies with the mechanism and is reported at 25% for all patients diagnosed with a diaphragmatic injury. Mortality is greatest in patients with blunt injury mechanisms in the acute setting due to associated injuries. The mortality from delayed presentation with herniation of abdominal contents into the thorax, from previous penetrating trauma, is around 20% and is substantially higher when bowel strangulation occurs. Since small injuries to the diaphragm are frequently missed, the exact incidence is unknown but is reported in the National Trauma Data Bank at about 0.5%. The rate of diaphragmatic injury appears to be increasing, perhaps related to better early trauma care, enhanced detection, and increased survival rates in patients with severe injuries.[5][6][7][8]

Pathophysiology

Penetrating Diaphragmatic Injury

The diaphragm separates the negative pressure thorax from the positive pressure abdomen and spans from the lower sternum anteriorly to as low as L3 posteriorly. Depending on the phase of respiration, the location can be quite variable, and wounds that appear to be remote from its perceived location may violate the diaphragm. Any penetrating injury to the abdomen or chest from the T4 through T12 dermatome anteriorly and the L3 region posteriorly should be considered to have potentially caused the diaphragmatic injury. Left-sided injuries are more common, possibly due to protective shielding by the liver but also perhaps due to the mechanism as most are related to stabbings and assailants are more likely to be right-handed thus inflicting injuries on the victim’s left. Penetrating injuries tend to be smaller, most measuring less than 2 cm. As a result, penetrating injuries are more likely to be occult and frequently result in delayed diagnosis. Penetrating injuries are most commonly associated with liver, hollow viscous, and splenic injuries.

Blunt Diaphragmatic Injury

Rupture of the diaphragm occurs when intra-abdominal pressure suddenly rises above the tensile strength of the diaphragmatic tissue. Blunt trauma produces larger, radial tears, often measuring 5 cm to 15 cm. Like penetrating injury, blunt diaphragmatic injuries occur most frequently on the left side which may be due to a congenital area of weakness in the diaphragm or because the liver attenuates some of the compressive force. When present, right-sided injuries to the diaphragm have a higher mortality rate due to more severe associated injuries. As compared to penetrating injuries, patients with blunt injury have a higher rate of injury to the aorta, lung, pelvis, and spleen.

Diaphragmatic injuries rarely occur alone and most patients have concomitant abdominal, head or thoracic injuries. Splenic rupture and liver laceration are not uncommon injuries in patients with diaphragmatic trauma.

History and Physical

Clinical presentation varies widely based on the mechanism of injury. Because the diaphragm is integral to normal respiration, patients with diaphragmatic injury may present in respiratory distress. Most often, blunt diaphragmatic injuries are discovered during the evaluation and management of the associated injuries. A physical exam should focus on the airway, breathing, and circulation, with inspection for signs of mediastinal shift or lung displacement. When herniation of abdominal contents occurs, bowel sounds may be auscultated in the chest. Any patient with penetrating trauma in the zone of concern (described above) should be assessed for diaphragmatic injury. Less than half of diaphragmatic injuries are diagnosed preoperatively, and a high index of suspicion based on the mechanism is required.

The physical exam should concentrate on the ABCDEs with a focus on the neck and chest. Some patients may have tracheal deviation, absent breath sounds, or asymmetrical chest expansion.

In most cases, the diagnosis is not made preoperatively and in 10-50% of patients, the diagnosis may be delayed for days or weeks. When patients present late, they usually have visceral or bowel herniation into the chest cavity. Strangulation, incarceration and even cardiac tamponade have been described in patients with delayed presentation.

Evaluation

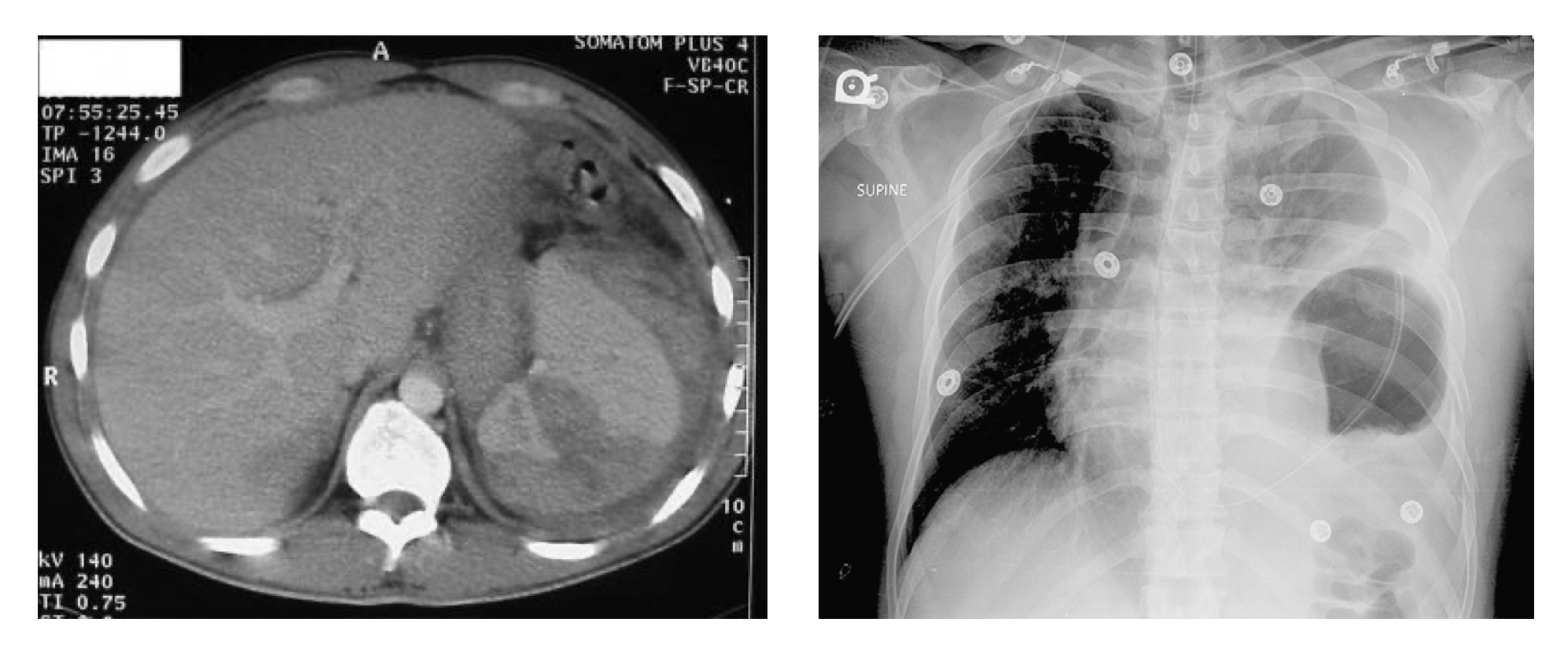

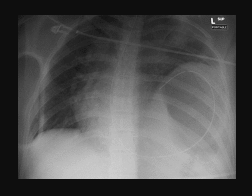

Chest Radiography

While findings may be obvious if there are bowel contents or a coiled nasogastric tube in the chest, chest radiographs are non-diagnostic in up to 40% of cases. This is particularly true in intubated patients as positive pressure ventilation prevents herniation of abdominal contents into the chest. Subtle findings may include elevation of the diaphragm, atelectasis or pleural effusion. Right-sided injuries, unless resulting in large defects, may be particularly difficult to identify on chest radiographs as the liver buttresses the diaphragm.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is frequently utilized in the early evaluation of trauma patients to assess for fluid in the abdomen, pericardium, and chest. An experienced operator may be able to visualize an injury to the diaphragm, but a negative study does not exclude the diagnosis.

Computed tomography (CT)

In hemodynamically stable patients, CT scanning may be useful in detecting diaphragmatic injury. Newer generation multidetector machines may detect even subtle injuries with a sensitivity of around 66.7%. However, most patients with penetrating injury still do not receive a correct preoperative diagnosis.

Thoracoscopy or Laparoscopy

Thoracoscopy may be used to visualize the diaphragm when the diagnosis is considered, but laparotomy is not required to manage other injuries. Laparoscopy has a sensitivity of about 88% and a sensitivity of nearly 100% in evaluating for diaphragmatic injury.

Treatment / Management

In the emergency department, a meticulous trauma evaluation with the management of the airway, breathing, and circulation is most important. Placement on an oral or nasogastric tube may be helpful in making the diagnosis if the tube remains in the chest and in decompressing the stomach contents thus preventing further herniation. In some settings, a chest tube, inserted carefully to avoid causing additional injury, should be placed to address associated hemothorax or pneumothorax. Injuries to the diaphragm do not heal spontaneously, so operative repair is required in almost all patients.

All left-sided injuries require repair, as do most right-sided injuries. In the rare patient with a small, right-sided tear that is a candidate for expectant management, it is important for the patient to understand the risk of delayed rupture. Surgical management is often via a transabdominal approach, typically during the laparotomy performed for other injuries. In less severely injured patients, a less invasive laparoscopic or even thoracoscopic approach may be appropriate.[9]

The actual repair is simple; once the herniated contents have been reduced, the rupture to the diaphragm can be closed with interrupted non-absorbable sutures. A chest tube should be left in the chest for a few days.

Differential Diagnosis

- Pneumothorax

- Blunt/Penetrating abdominal trauma

- Pneumoperitoneum

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients who are managed right away is good. Early deaths are most often due to other associated injuries. Re-expansion pulmonary edema has been reported after laparotomy in rare cases. Sometimes diaphragmatic paralysis may occur if the laceration was in the vicinity of the phrenic nerve. However, in most cases, resolve over a few months.

Complications

- Complications include:

- Bowel herniation, incarceration, strangulation

- Tension pneumothorax/hemothorax

- Pericardial tamponade

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis of a diaphragmatic rupture is not easy, especially when the tear is small. Hence, the condition is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a radiologist, general surgeon, thoracic surgeon, and a trauma surgeon. Nurses who look after patients with penetrating or blunt trauma should be aware of missed diaphragmatic injuries. Difficulties in breathing, bowel sounds in the chest and an abnormal chest x-ray should be a concern and reported to the surgeon.

Once diagnosed, the only treatment for a diaphragmatic tear is surgery. The surgery may be approached via the abdomen or thorax. Nurses should ensure that these patients have DVT and pressure sore prophylaxis. If a chest tube has been left in after surgery, it should be monitored for air and fluid leaks. Open communication between the team members is vital for good outcomes.

In most cases, if there are no other injuries, the outcomes are excellent. However, if the diagnosis is missed, it can present later with herniation of bowel contents in the chest.[10] (Level V)