Introduction

The trace element iron is essential for optimal physiological functioning and overall health and must be derived from dietary food sources and supplements. The body cannot synthesize iron, but macrophages can recycle and reuse it from senescent erythrocytes. Some iron is lost daily from occult stool and urine blood losses and the desquamation of skin and endothelial cells and must be replaced.[1][2]

Iron facilitates the transportation of oxygen throughout the bloodstream via hemoglobin in erythrocytes. Iron is also a component of myoglobin, aiding in storing and releasing oxygen within muscle cells, and contributes to enzymatic reactions in energy production, DNA and amino acid synthesis, and immune function.

The average amount of iron in an adult male is approximately 3 to 4 grams, of which three-quarters are heme proteins, such as hemoglobin, myoglobin, cytochromes, and peroxidases. About 20% to 30% of total body iron exists in the form of storage proteins, including ferritin and hemosiderin.[3]

This activity reviews the dietary needs, sources, absorption, and function of iron and the clinical significance of its deficiency.

Function

Iron is absorbed in the small intestine, primarily in the duodenum and upper jejunum. Once absorbed, most binds to transferrin, a transport protein that delivers it to the bone marrow for erythropoiesis. The liver takes up non–transferrin-bound iron and stores it as ferritin.[4] This prevents significant amounts of iron from existing in its free form, which could damage proteins and cell membranes by free radical formation.

Iron is an essential component of hemoglobin, the protein within erythrocytes responsible for binding and transporting oxygen from the lungs throughout the body, and is necessary for cellular metabolism, energy production, and overall tissue function. Iron is also a component of the muscle protein myoglobin that ensures adequate oxygen supply for muscle function. Another role of iron is as a cofactor for enzymes involved in energy metabolism, DNA and amino acid synthesis, hormone synthesis, and immune function.

Iron balance is mainly regulated by the amount of iron absorption rather than elimination. Unlike other minerals, there is no active physiologic process of excretion. The peptide hepcidin, produced by hepatocytes, helps regulate iron homeostasis. High levels of iron in the body stimulate hepcidin production, which decreases iron absorption and promotes iron sequestration within cells, preventing iron overload. Conversely, low iron levels or anemia reduce hepcidin production, allowing increased absorption of dietary iron and release of stored iron into the circulation to meet the body's needs.[5][6]

Issues of Concern

Iron absorption involves heme iron from animal-based foods and non-heme iron from plant-based foods and supplements. Heme iron, present in meats, poultry, and seafood, is more readily absorbed and has a higher bioavailability than non-heme iron. Once consumed, heme iron is released from ingested proteins in the stomach's acidic environment and the small intestine.

Non-heme iron, found in plant sources such as beans, nuts, dark chocolate, legumes, spinach, and fortified grains, has about two-thirds the bioavailability of heme iron. About 25% of dietary heme iron is absorbed, while 17% or less of dietary non-heme iron is absorbed. Iron bioavailability is estimated to be 14% to 18% for those consuming animal products and as low as 5% to 12% for plant-based eaters.[7] Heme iron contributes about 10% to 15% of total dietary iron intake in Western populations, but its higher bioavailability results in it being approximately 40% of the total iron absorbed.[8] The percentage of non-heme iron absorbed increases as body iron stores decrease. Generally, heme iron is absorbed more efficiently than non-heme iron but is unaffected by an individual's iron status.

Many factors influence iron intake, absorption, and individual requirements. Some dietary components either enhance or inhibit absorption. For example, the heme iron in meats, fish, and poultry (called the "MFP factor") significantly increases iron absorption from non-heme sources such as fruits, vegetables, and grains when consumed together.[9] One study demonstrated that adding chicken, beef, or fish to a meal increased non-heme iron absorption 2 to 3 fold but found no difference when the same quantity of protein in the form of egg albumin was added.[10] The precise underlying mechanism is unclear, but evidence suggests that cysteine-containing peptides in animal products aid in forming luminal carriers to promote iron transportation.[11] Vitamin C enhances the absorption of non-heme iron due to its iron-chelating and reducing abilities, converting ferric iron to ferrous iron, which is more soluble.[12][13] Vitamin C also counteracts iron absorption inhibitors such as phytates in grains and legumes, polyphenols in tea, coffee, and red wine, and calcium in dairy products.[8] This is the physiological basis for taking iron supplements with a vitamin C–containing food or juice rather than milk.

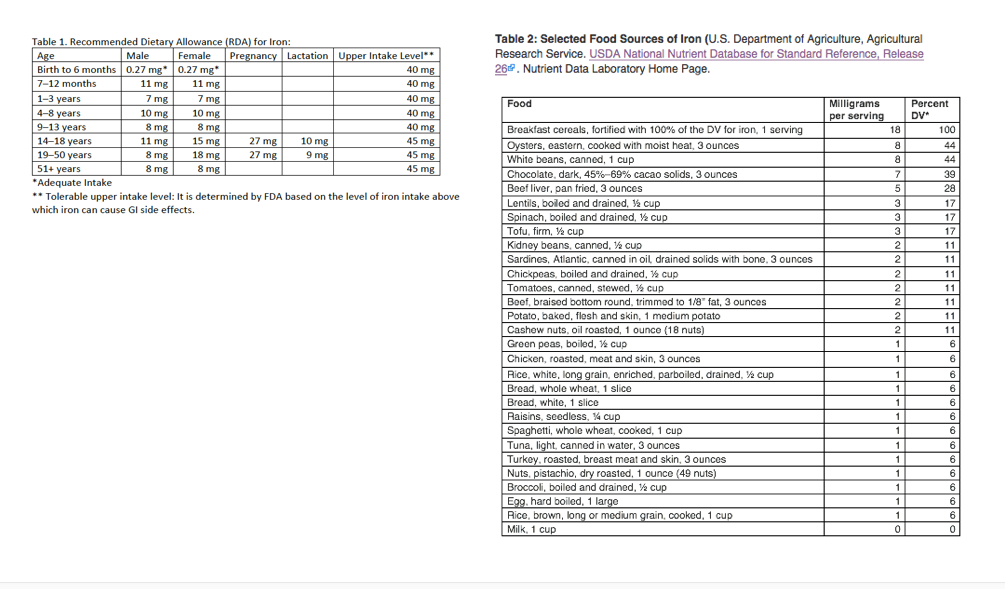

Population and individual factors influence iron dietary consumption and requirements. Since non-heme iron is less bioavailable than heme iron, people consuming a plant-based vegan or vegetarian diet require a higher intake than individuals consuming animal products. The recommended daily allowance (RDA) for iron ranges from 0.27 mg daily during infancy to 27 mg daily during pregnancy. The RDA for menstruating females is 18 mg daily and 8 mg for women past reproductive age and adult men. Breast milk contains relatively low levels of highly bioavailable iron, and controversy exists regarding the need to supplement with fortified foods or iron drops and at what age to do so. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that breastfed, full-term infants begin 1mg/kg/day of supplemental iron at 4 months and continue for the duration of exclusive breastfeeding.[14] Cow milk is relatively low in iron, containing only about 0.1 to 0.2 mg per 240 mL (1 cup), and is not suitable for infants who should drink iron-fortified infant formula (3 mg per 240 mL) if they are not breastfeeding.

Iron needs are higher during the adolescent growth spurt, as girls begin menstruation and boys markedly increase their hemoglobin concentration.[14] Menstruating females have an average daily iron loss of about 2 mg, which dietary sources must replace to prevent iron deficiency. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) that causes ongoing uterine bleeding and blood donation can also increase dietary iron requirements. On the other hand, oral contraceptives often decrease menstrual blood loss and lower iron needs. People from less economically developed regions may experience food insecurity, resulting in iron deficiency and malnutrition. In addition, these geographic areas may experience a higher prevalence of parasitic intestinal infections, leading to malabsorption and gastrointestinal blood loss, resulting in increased dietary iron requirements.[15]

Medical conditions that interfere with iron absorption include celiac disease, Crohn disease, malabsorptive disorders, and a history of gastric bypass surgery. Patients with these disorders also have increased iron needs and often require supplementation to maintain adequate stores.

Whole foods, fortified foods, and supplements are the primary sources of iron. The RDA depends on an individual's age, stage of life, and sex. See Table below. Red meat, poultry (especially the darker meat in thighs and drumsticks), fish, and shellfish are rich sources of heme iron. These foods also contain some non-heme iron. Foods containing exclusively non-heme iron include legumes, dark leafy greens, nuts, seeds, whole grains, and dried fruits. Most non-heme iron is found in plant-based foods; eggs are the exception, as they are an animal-based food containing non-heme iron. Many processed foods, like bread, cereal, and nutritional drinks, are fortified with non-heme iron, representing about half of daily dietary iron intake in the US.

Eating vitamin C-rich foods such as citrus fruits, bell peppers, and tomatoes with foods plentiful in non-heme iron can increase iron absorption. Avoiding beverages like tea and coffee that contain phytates and calcium-containing milk during meals improves the absorption of non-heme iron. Table 2 illustrates the iron content of common foods and the percent of daily value (DV) from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Nutrient Database. Foods providing 20% or more of the DV are considered high nutrient sources, but foods providing lower percentages also contribute to a healthful diet.

Cooking food in iron cookware significantly improves the iron content of foods. Studies have shown that iron content and absorption are 1.5 to 3.3 times higher when meats, vegetables, and legumes are prepared in iron pots, resulting in increased hemoglobin levels in individuals compared to those using non-iron vessels.[16]

Iron supplements are widely available when dietary intake does not meet nutritional needs. These include multivitamins with iron and iron-only preparations, which can usually be purchased without a prescription. These are reviewed in detail in the StatPearls companion topics "Iron Supplementation" and "Iron Deficiency Anemia."

The table below lists the iron content of selected animal and plant-based foods from the US National Institutes of Health Iron Factsheet.

Table. Iron Content of Selected Foods

| Food |

Mg Iron Per Serving |

Percent DV |

| Breakfast cereals, fortified with 100% of the DV for iron, 1 serving |

18 |

100 |

| Oysters, eastern, cooked with moist heat, 3 ounces |

8 |

44 |

| White beans, canned, 1 cup |

8 |

44 |

| Beef liver, pan-fried, 3 ounces |

5 |

28 |

| Lentils, boiled and drained, ½ cup |

3 |

17 |

| Spinach, boiled and drained, ½ cup |

3 |

17 |

| Tofu, firm, ½ cup |

3 |

17 |

| Chocolate, dark, 45%–69% cacao solids, 1 ounce |

2 |

11 |

| Kidney beans, canned, ½ cup |

2 |

11 |

| Sardines, Atlantic, canned in oil, drained solids with bone, 3 ounces |

2 |

11 |

| Chickpeas, boiled and drained, ½ cup |

2 |

11 |

| Tomatoes, canned, stewed, ½ cup |

2 |

11 |

| Beef, braised bottom round, trimmed to 1/8" fat, 3 ounces |

2 |

11 |

| Potato, baked, flesh and skin, 1 medium potato |

2 |

11 |

| Cashew nuts, oil roasted, 1 ounce (18 nuts) |

2 |

11 |

| Green peas, boiled, ½ cup |

1 |

6 |

| Chicken, roasted, meat and skin, 3 ounces |

1 |

6 |

| Rice, white, long grain, enriched, parboiled, drained, ½ cup |

1 |

6 |

| Bread, whole wheat, 1 slice |

1 |

6 |

| Bread, white, 1 slice |

1 |

6 |

| Raisins, seedless, ¼ cup |

1 |

6 |

| Spaghetti, whole wheat, cooked, 1 cup |

1 |

6 |

| Tuna, light, canned in water, 3 ounces |

1 |

6 |

| Turkey, roasted, breast meat and skin, 3 ounces |

1 |

6 |

| Nuts, pistachio, dry roasted, 1 ounce (49 nuts) |

1 |

6 |

| Broccoli, boiled and drained, ½ cup |

1 |

6 |

| Egg, hard-boiled, 1 large |

1 |

6 |

| Rice, brown, long or medium grain, cooked, 1 cup |

1 |

6 |

| Cheese, cheddar, 1.5 ounces |

0 |

0 |

| Cantaloupe, diced, ½ cup |

0 |

0 |

| Mushrooms, white, sliced and stir-fried, ½ cup |

0 |

0 |

| Cheese, cottage, 2% milk fat, ½ cup |

0 |

0 |

| Milk, 1 cup |

0 |

0 |

Clinical Significance

Dietary iron deficiency affects more than 1.6 billion people globally. It is more prevalent in resource-limited areas but still affects approximately 10% of toddlers, young girls, and women of childbearing age in the US and Canada. Iron deficiency progresses through stages, from asymptomatic iron depletion to iron deficiency anemia. Iron toxicity occurs only with excess supplement consumption, including accidental ingestions, and in genetic conditions causing iron overload, such as hemochromatosis. Because the body absorbs less iron when stores are adequate, toxicity is unlikely to occur solely by eating iron-rich foods. See StatPearls companion topics "Iron Deficiency Anemia," "Chronic Iron Deficiency," and "Iron Supplementation."

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The trace mineral iron facilitates oxygen transport via hemoglobin, is a component of myoglobin, and is involved in energy production, DNA synthesis, and immune function. Maintaining adequate iron levels is essential for optimal physiological functioning and overall health. Since the body cannot synthesize iron, it must be derived from dietary sources or supplements. Heme iron, present in meats, poultry, and seafood, is more readily absorbed and has a higher bioavailability than non-heme iron. Non-heme iron, mainly found in plant sources such as beans, nuts, dark chocolate, legumes, spinach, and fortified grains, has about half the bioavailability of heme iron. However, it represents a significant percentage of iron absorbed when a diet includes diverse plant-based foods.

The interprofessional healthcare team can collaborate to improve patient care by educating patients on the importance of consuming adequate amounts of iron-containing foods. Primary care nurses and clinicians can work together to prevent nutritional deficiencies by obtaining patient dietary histories, providing specific advice about iron needs for different stages of life, answering patient questions, and advocating for healthy foods in local school meals, food pantries, and nutrition programs. They can coordinate services with registered dieticians, nutritionists, subspecialists, and pharmacists for patients with medical conditions requiring consultation. All team members can counsel patients about iron-rich foods, interactions with foods and beverages that enhance or hinder absorption, and when indicated, how to take supplements safely. The healthcare team must be aware of special populations at risk for iron deficiency due to inadequate nutrition or physiologic needs and screen and educate them to ensure optimal health.