Continuing Education Activity

Pleural effusion is the abnormal accumulation of fluid within the pleural space, the thin cavity between the pleural layers surrounding the lungs. Pleural effusions can arise from various etiologies, ranging from heart failure and pneumonia to malignancies, such as lung cancer, and systemic inflammatory disorders, such as lupus. Fluid accumulation in the pleural space can compress the lungs, impairing their ability to expand fully during inspiration and causing respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath, chest pain, and cough.

Pleural effusion is a marker of increased mortality and morbidity in specific populations. Diagnosing pleural effusion typically involves a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and diagnostic procedures such as thoracentesis. The management of pleural effusion depends on its etiology and severity and may include treating the underlying condition, draining the accumulated fluid, and addressing complications such as infection or recurrence.

This activity for healthcare professionals reviews the evaluation and management of pleural effusion by increasing proficiency in diagnosing pleural effusion through clinical assessment and interpretation of imaging studies and pleural fluid analysis and highlights the important role of interprofessional collaboration to improve patient outcomes with pleural effusion.

Objectives:

Identify the causes of pleural effusion based on a patient's clinical presentation and diagnostic test results.

Differentiate between transudative and exudative pleural effusions based on laboratory pleural fluid analysis and clinical judgment.

Determine a personalized management strategy for a patient with pleural effusion.

Implement interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance retrobulbar block and improve outcomes.

Introduction

A pleural effusion is an abnormal accumulation of fluid within the pleural space. Under normal circumstances, a small amount of fluid is continuously produced and reabsorbed within this space to maintain lubrication and facilitate smooth movement of the lungs during respiration. However, various pathological processes can disrupt this equilibrium, leading to excessive fluid accumulation. In the United States alone, approximately 1.5 million patients are affected annually.[1][2] A pleural effusion is a marker of increased morbidity and mortality in certain populations.[3]

Pleural effusion is diagnosed using a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and laboratory studies, particularly pleural fluid analysis. Thoracentesis is both diagnostic and therapeutic for patients with this condition. Management strategies for this condition include treating the underlying cause, draining the accumulated fluid, and addressing complications such as infection and pleural fibrosis.

Pleural Space Anatomy

The lungs, enclosed within the bony thorax, expand and contract during respiration with the assistance of the pleural space. This space is between the visceral and parietal pleura and typically contains a thin layer of fluid that allows for smooth lung movements during respiration.

The pleurae consist of the visceral and parietal layers and are integral to the thoracic cavity's anatomy. The visceral pleura is tightly adherent to the lung surface and forms a continuous covering that follows the contours of the lung lobes and fissures. The visceral pleura comprises a single mesothelial cell layer supported by connective tissue. This layer provides a frictionless surface that facilitates lung expansion and contraction during respiratory cycles. The parietal pleura lines the thoracic cavity's inner surface and is divided into the mediastinal, diaphragmatic, costal, and cervical portions. This outer layer is thicker and more vascularized compared to the visceral pleura and contains sensory nerve fibers contributing to pain perception.

The visceral and parietal pleurae enclose the pleural cavity, a potential space typically containing only a minimum volume of pleural fluid. This fluid minimizes friction between the pleural layers during respiratory movements. The volumetric fluid balance within the pleural space is determined by gravity, ventilatory motion, and hydrostatic and oncotic pressures.[4]

Disorders affecting the pleurae, such as pleural effusion or pleurisy, can disrupt these functions, leading to respiratory symptoms and complications. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of pleural space anatomy and physiology is essential for effectively diagnosing and managing conditions involving these structures.

Etiology

Pleural effusion is caused by various conditions and is classified by Light's criteria as either a transudate or exudate. Differentiating between exudative and transudative fluids is essential in determining the underlying pathophysiology and subsequent diagnostic planning. Light's criteria serve as a reference standard for assessing pleural fluid parameters, including the quantitative ratio of pleural fluid lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) to serum LDH levels and the ratio of pleural fluid protein to serum protein levels. An exudative effusion is diagnosed if one or more of the following criteria are met:

- Pleural fluid protein/serum protein ratio of more than 0.5

- Pleural fluid LDH/serum LDH ratio of more than 0.6

- Pleural fluid LDH is more than two-thirds of the upper limit of the normal serum LDH value [5][6]

If none of these criteria are met, the fluid is considered transudative.

According to Heffner's criteria, a modification to Light's, an exudative effusion is characterized by one or more of the following:

- Pleural fluid protein level exceeding 2.9 g/dL

- Pleural fluid cholesterol level greater than 45 mg/dL

- Pleural LDH level greater than two-thirds of the upper limit of normal serum LDH [7]

Common causes of transudative pleural effusion include conditions that alter the hydrostatic or oncotic pressures in the pleural space, such as left heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, hypoalbuminemia, or peritoneal dialysis. Common causes of exudative pleural effusion include pulmonary infections, such as pneumonia or tuberculosis; malignancy; inflammatory disorders, such as pancreatitis, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis; postcardiac injury syndrome; chylothorax; hemothorax; post-coronary artery bypass grafting (post-CABG); and benign asbestos pleural effusion.

Less common causes of pleural effusion include pulmonary embolism (exudative or transudative), drug-induced reactions (exudative), radiotherapy (exudative), esophageal rupture (exudative), and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (exudative). Drugs commonly associated with pleural effusion development include methotrexate, amiodarone, phenytoin, and dasatinib.[8][9]

Epidemiology

Pleural effusion is the most common pleural space disease, affecting 1.5 million patients annually in the United States and leading to significant healthcare costs.[10]However, insufficient large-scale epidemiological studies exist surrounding its various etiologies. Based on currently available data, the condition's occurrence rate appears to differ geographically. Notably, heart failure, malignant pleural effusion, and parapneumonic effusions account for the majority in terms of annual incidence.

Pathophysiology

The amount of fluid in the pleural space is typically around 0.1 to 0.3 mL/kg, significantly influencing the hydromechanical coupling between the lung and chest wall. Pleural fluid is derived from the blood vessels of the parietal pleural surfaces, filtered out by the hydrostatic pressure of systemic vessels. This fluid is subsequently reabsorbed through the lymphatic vessels, primarily located in the dependent portions of the pleural cavity.

Accumulation of excess fluid can occur from various mechanisms. Simplistically, excessive production or decreased absorption can overwhelm the normal homeostatic mechanisms within the pleural space. The pathophysiology of pleural effusion includes several mechanisms, including increased pulmonary capillary pressure, as observed in heart failure and renal failure, and increased pulmonary capillary permeability, commonly associated with pneumonia. Pleural effusion can also result from decreased intrapleural pressure, such as in atelectasis, and decreased plasma oncotic pressure, as observed in hypoalbuminemia. In addition, pleural effusion can arise due to increased pleural permeability from infections or inflammation, obstruction of pleural lymphatic drainage by malignancies, and fluid migration from other sites or cavities such as the peritoneum or retroperitoneum. Furthermore, rupture of thoracic vessels, leading to haemothorax or chylothorax, and drug-induced effects can also contribute to the development of pleural effusion.[11][12]

History and Physical

Pleural effusion symptoms can vary from no discernible signs to exertional breathlessness, depending on the restriction of thoracic movement. The pathophysiology associated with pleural effusion is not fully understood in the scientific literature. The amount of effusion seems to correlate poorly with the severity of symptoms. The impact of effusion on thoracic expansion appears to exert the most salient influence. Additional plausible etiologies include oxygen impairments and coexisting intraparenchymal diseases, such as pulmonary edema in the setting of heart failure.[13]

The patient may present with symptoms such as cough, fever, and systemic signs, depending on the underlying cause of the effusion. Although rare, effusions can occasionally attain a size significant enough to induce hemodynamic changes, imitating tamponade physiology. Patients with active pleural inflammation called pleurisy complain of sharp, severe, localized crescendo-decrescendo pain with breathing or coughing. Pleuritic pain tends to subside when an effusion develops. Constant pain is also a hallmark of malignant diseases such as mesothelioma.

The physical examination findings can range from subtle to florid. Intercostal space fullness and percussion dullness are appreciated in large effusions. Auscultation reveals decreased breath sounds and tactile and vocal fremiti. Egophony is most pronounced in the superior aspect of effusion. Pleural rubs, often mistaken for coarse crackles, can be heard during active pleurisy without any effusion.

As pleural effusion results from varied diseases, history should focus on the causes of miscellaneous pulmonary and systemic effusions. Inquiring about a patient's comorbidities, medications, clinical indicators for infectious diseases, and predisposing factors to malignancies is advisable. A comprehensive physical examination should also encompass various potential diagnostic considerations. For example, congestive heart failure should be suspected in a patient with jugular venous distension, S3 heart sound, and pedal edema. Advanced liver cirrhosis should be considered in individuals with ascites and caput medusae.

Evaluation

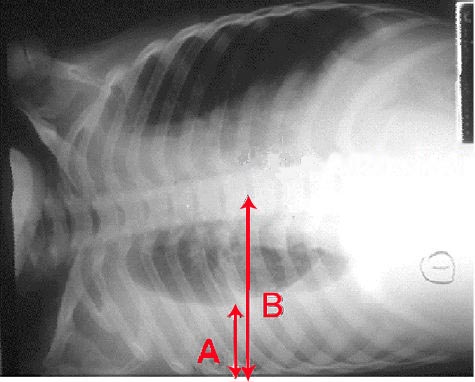

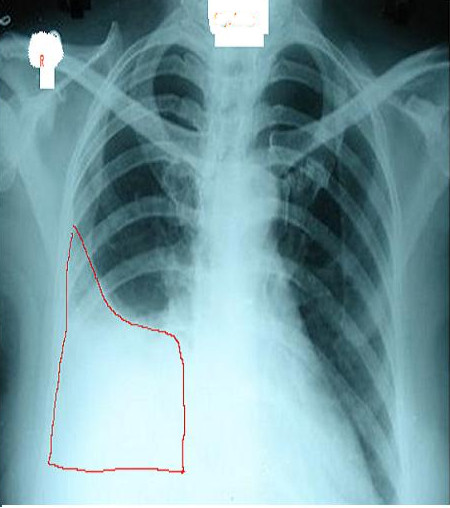

A chest radiograph is an excellent initial imaging study for identifying pleural effusion. In an upright posteroanterior view, the meniscus sign indicates the presence of a significant amount of pleural fluid, typically exceeding 200 mL and blunting the costophrenic angle (see Image. Right Lung Pleural Effusion Radiograph, Posteroanterior). In lesser quantities of pleural effusion, blunting of the costophrenic angles on posteroanterior erect chest roentgenograms serves as a clue to elicit further investigations. However, a lateral decubitus view can detect as little as 50 mL of fluid in the pleural space (see Image. Pleural Effusion Radiograph, Lateral Decubitus).[15] Ultrasound is more sensitive and is readily available for diagnosing and confirming an effusion and planning a thoracentesis.[7][8][14]

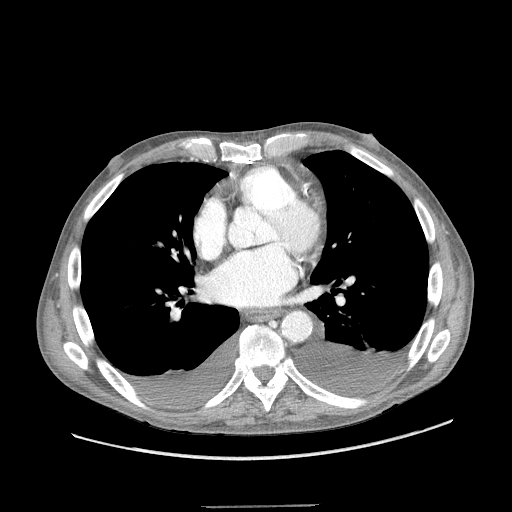

All initial effusion occurrences warrant a thoracentesis to ascertain the underlying etiology of the condition, except in instances where heart failure is confidently suspected. In such cases, a trial of diuresis may be conducted as a preliminary measure. Incorporating thoracic ultrasound in management planning is crucial. This test's prompt availability and rapid performance reduce the need for ancillary diagnostic testing such as computed tomography (CT) and offer valuable insights into fluid characteristics, which can aid in diagnosis (see Image. Bilateral Pleural Effusions on Chest Computed Tomography).[15] In addition, thoracic ultrasound assists in differentiating fluid accumulation from other conditions that present as radiopaque abnormalities on chest radiographs, such as pneumonia or atelectasis.

Pleural fluid appears hypoechoic on ultrasound. The dependent chest area and surrounding anatomical structures must be examined for better visualization. Effusion echogenicity must be noted since features such as septations may indicate a complex effusion arising from conditions such as parapneumonic effusion or empyema. The hematocrit sign is characterized by smoke-like shadows, which may indicate the presence of a hemothorax. A complex-appearing fluid collection necessitates planning for chest tube thoracostomy (CTT).

Blood tests should include a complete blood count with differential (a leukocytosis may indicate infection, bleeding, or malignancy), serum electrolytes, urea, creatinine, liver function tests and enzymes, albumin, lipase, and cardiac enzymes. Routinely assessed biomarkers after thoracentesis include fluid pH, fluid and serum protein levels, fluid and serum LDH levels, fluid glucose levels, fluid cell count differential, fluid gram stain, and culture. Fluid cytology may also be examined in specific situations. Light's criteria may then be applied to classify the fluid as an exudate or transudate. Light's criteria should be interpreted within the clinical context as it has been reported to misclassify 25% to 30% of transudates as exudates in heart failure-related pleural effusion. In such instances, obtaining a fluid B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) or computing the albumin or protein gradient between serum and pleural fluid is helpful. A serum-to-pleural fluid albumin ratio exceeding 1.2 g/dL or a serum-to-pleural fluid total protein gradient greater than 2.5 g/dL in suspected heart failure could indicate a transudative effusion.[16]

Exudative effusions require further investigation to identify the underlying cause. In some cases, cell count differentials can aid in narrowing down potential diagnoses. A primarily lymphocytic effusion may suggest tuberculosis, post-CABG, rheumatoid arthritis, yellow nail syndrome, chylothorax, or malignancy. Eosinophilia in pleural effusion is rare and typically observed in pneumothorax, hemothorax, parasitic disease, or drug-induced effusion. Parapneumonic effusions show a neutrophil-predominant cell count. Pleural LDH values exceeding 1000 U/L are observed in tuberculosis, lymphoma, and empyema. A pH below 7.2 indicates a complex pleural effusion in the setting of pneumonia, which almost always requires CTT insertion for drainage. Low pH levels may also indicate esophageal rupture or rheumatoid arthritis.

Condition-specific markers, such as acid-fast bacilli smear, Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture, and adenosine deaminase, are indicated when tuberculosis is suspected. Amylase levels are evaluated if pancreatitis-related effusion is apparent. Pleural fluid triglycerides greater than 110 mg/dL signify a chylothorax. The pleural fluid in such conditions typically has a milky-white appearance. Hemothorax can be established if the pleural fluid hematocrit is more than 0.5 times that of the serum hematocrit.

Cytological testing is necessary in suspected cases of malignant pleural effusion. The sensitivity of pleural fluid cytology for diagnosing malignant effusions after the first thoracentesis is approximately 60%. However, the diagnostic yield increases with additional attempts, achieving a success rate of up to 90% after 3 samples are collected on separate days. A medical thoracoscopy with pleural biopsy is recommended after 2 successive thoracenteses if a malignant effusion is highly suspected despite negative cytology results.[17]

Invasive procedures are available to investigate exudative effusions that yield unclear results in noninvasive diagnostic tests, including closed-needle and image-guided needle biopsies, thoracoscopy, or video-assisted thoracic surgery. The clinical presentation is generally sufficient to identify a transudative effusion's cause, and additional testing may not be necessary. Nonetheless, considering less common causes, such as trapped lung, is essential where pleural elastance measurements may be required. Urinothorax is another common cause of effusion, requiring pleural and serum creatinine levels for diagnosis.

Treatment / Management

Management primarily focuses on identifying and treating the underlying cause of pleural effusion. Pleural fluid drainage is recommended for symptomatic patients. In asymptomatic patients, drainage is performed only as part of the diagnostic process unless signs and symptoms of hemorrhage or infection are present. A thoracentesis in the setting of heart failure is recommended only if diuretics fail or the patient is significantly symptomatic. Chylous effusions are initially managed conservatively, although some require surgery.

Thoracentesis is a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure. Current recommendations when performing a thoracentesis include the following:

- Bedside ultrasound improves success rates and reduces the risk of pneumothorax during fluid aspiration.[18]

- Ultrasound can detect pleural fluid sequestrations.

- Always send fluid for biochemistry, culture, and cytology.

- Use Light's criteria to distinguish exudate from transudate.[19]

- Lymphocyte-predominant effusions are typically due to malignancy and tuberculosis.[20]

- Check pH when aspirating pleural effusions.

- Do not inject air or local anesthetic into the sample, which may alter the fluid's pH.

- Malignant effusions can be detected on cytology (40% to 60%).

Chest tube drainage with antibiotic treatment is warranted in complex parapneumonic effusions or empyema. Small-bore drains, ranging from 10- to 14-gauge, are as effective as larger drains and may be preferable due to their ease of placement and reduced patient discomfort. Intrapleural fibrinolytic and DNase administration can be utilized to enhance drainage. However, thoracoscopic decortication may be necessary when these measures fail.[21]

Patients diagnosed with malignant effusion typically do not require frequent drainage procedures unless infection or severe symptoms arise. Individuals requiring frequent drainage may opt for pleurodesis or tunneled catheter placement. In any case, limiting fluid extraction to no more than 1500 mL per session is important to avoid the risk of reexpansion pulmonary edema.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of pleural effusion includes the following:

Transudative Effusions:

- Cardiovascular: Common causes include congestive heart failure and pulmonary embolism.

- Infradiaphragmatic: Conditions such as cirrhosis and peritoneal dialysis often result in transudative effusions.

- Other: Additional causes include nephrotic syndrome and hypoalbuminemia, which may arise from malnutrition, and renal or liver failure.

Exudative Effusions:

- Infections (most common):

- Bacterial: Includes sepsis and pneumonia.

- Tuberculosis: Still a significant cause of exudative effusion in developing countries.

- Viral: Often associated with respiratory, hepatic, and cardiac infections.

- Fungal and parasitic: Less common but notable etiologies, especially in Africa and South America.

- Neoplasm:

- Primary lung cancer: A frequent cause of exudative effusions.

- Metastatic disease: Most commonly from lung, breast, colon, and ovarian cancers.

- Mesothelioma: An important differential to consider, especially in patients with a history of exposure to carcinogenic agents, such as asbestos.

- Infradiaphragmatic:

- Conditions such as pancreatitis, peritonitis, bilothorax due to biliopleural fistula or bile duct obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease, intraabdominal abscess, and postendoscopic esophageal sclerotherapy are notable causes.

- Meigs syndrome: Characterized by pleural effusion and ascites in the presence of pelvic tumors.

- Autoimmune: Various autoimmune conditions can lead to exudative effusions.

- Drugs: Certain medications may induce pleural effusion.

- Post-operative: Surgical procedures can result in exudative effusions, such as chylothorax and hemothorax.

- Other: Includes amyloidosis, esophageal rupture, and benign asbestos-related effusion.

A thorough clinical evaluation and appropriate use of imaging and laboratory tests can differentiate pleural effusion from these conditions.

Prognosis

Limited data regarding the prognostic factors associated with pleural effusion are available. Although it is already established that individuals with malignant effusions carry a dismal prognosis, the mortality rate for those with nonmalignant effusions has not been extensively studied.[22][23][22] Nevertheless, several prospective studies have indicated that effusion is a potential indicator of increased mortality.[3][24]

Complications

Pleural effusion, although often manageable, can lead to various complications. One such complication is empyema, characterized by accumulated infected fluid within the pleural space. Empyema can result in systemic infection, sepsis, and respiratory compromise, necessitating aggressive treatment with antibiotics and, in severe cases, drainage procedures such as thoracentesis or CTT insertion.

Another potential complication of pleural effusion is pleural thickening from fibrous adhesions, which can occur due to chronic inflammation or repeated effusion episodes. Pleural thickening can lead to decreased lung expansion, impaired respiratory function, and restrictive lung disease. Although pulmonary rehabilitation or corticosteroids may suffice for some patients, others may require surgical intervention, such as thoracoscopic or open decortication, to remove fibrous tissue and release adhesions, thereby improving lung expansion and respiratory function.

Consultations

The following consultations are recommended:

- Pulmonology: To assess the severity of pleural effusion, determine treatment options, and coordinate care with other team members.

- Thoracic surgery: To perform surgical procedures involving the chest, including interventions that address complicated pleural effusion.

These medical specialists can help provide comprehensive care tailored to the patient's requirements.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Primary preventive measures for pleural effusion involve preventing the development of conditions that can lead to its occurrence. These preventive actions include engaging in regular physical activity, maintaining a healthy diet, limiting alcohol consumption, and abstaining from smoking. Vaccinating against infectious diseases such as pneumonia and influenza can also help prevent respiratory infections that may contribute to pleural effusion. Occupational safety measures, such as proper respiratory protection in workplaces with potential exposure to hazardous materials, can also reduce the risk of developing pleural effusion due to occupational lung diseases.

Secondary preventive measures focus on early detection and intervention to prevent complications associated with pleural effusion. Regular health check-ups, particularly for individuals with underlying risk factors such as heart or lung conditions, can facilitate early identification of symptoms suggestive of pleural effusion. Diagnostic tests such as chest x-rays and CT scans may be recommended for individuals with respiratory symptoms or those at high risk for pleural effusion. Timely treatment of underlying medical conditions, such as heart failure or pneumonia, can help prevent the progression of these conditions to pleural effusion. Appropriate management of existing pleural effusions, including drainage procedures and addressing underlying causes, can prevent complications such as infection or recurrence.

Pearls and Other Issues

Pleural effusion is characterized by an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the pleural space, resulting from various underlying conditions such as heart failure, infection, or malignancy. Diagnosis typically involves imaging studies such as radiography and CT scanning, followed by thoracentesis for fluid analysis. Treatment depends on the cause and severity of symptoms, ranging from addressing the underlying condition to draining the fluid and performing pleurodesis in some cases. Complications, including respiratory compromise and infection, require prompt recognition and management. Multidisciplinary collaboration among healthcare specialties is often necessary for comprehensive care.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The interprofessional team managing pleural effusions includes specialists from various fields collaborating to ensure comprehensive patient care. Pulmonologists play a central role in diagnosing and treating respiratory conditions, assessing effusion severity, and coordinating care plans. These specialists collaborate closely with cardiothoracic surgeons who perform procedures to treat complex cases or prevent recurrence. Radiologists provide expertise in interpreting imaging studies, aiding in accurate diagnosis and treatment planning. Pathologists analyze fluid and tissue samples to confirm diagnoses and rule out malignancies or infections. Additional specialists, such as oncologists, infectious disease experts, cardiologists, interventional radiologists, and hepatologists, may be involved depending on the underlying cause of the pleural effusion.

Respiratory therapists offer respiratory care and assist in managing symptoms through techniques such as breathing exercises and oxygen therapy. Nurses play a crucial role in patient education, care coordination, and monitoring patient progress throughout treatment. Physical therapists develop tailored exercise programs to optimize lung function and mobility, particularly following procedures. By working collaboratively, this interprofessional team ensures that patients with pleural effusions receive comprehensive, personalized care to enhance outcomes and quality of life.[25][26]