Introduction

The extensor hallucis longus muscle is one of four muscles in the anterior compartment of the lower limb.[1] The three other muscles in the anterior compartment are the tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, and fibularis tertius muscles. The anterior compartment receives innervation from the deep fibular nerve, supplied by the anterior tibial artery, and is important in the dorsiflexion of the ankle and extension of the toes. The extensor hallucis longus specifically extends the hallux, dorsiflexes the foot at the ankle, and inverts the foot. The extensor hallucis longus muscle is susceptible to several pathologies, including nerve injury resulting in foot drop, tendonitis, tendon rupture, and anterior compartment syndrome.

Structure and Function

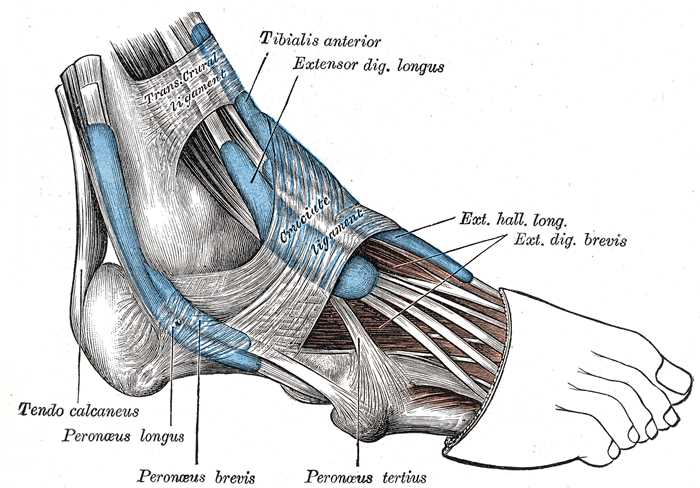

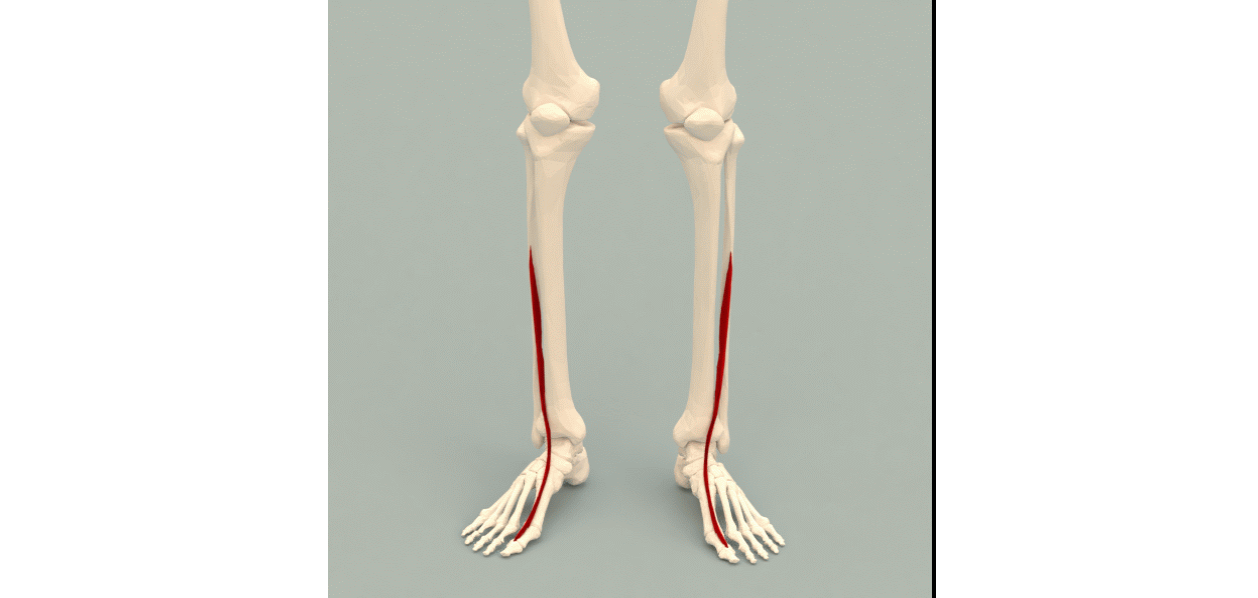

The extensor hallucis longus arises from the anterior surface of the fibula and inserts at the base and dorsal center of the distal phalanx of the hallux. Its location is between the tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus muscles on the anterior side of the lower limb, coursing inferiorly and medially to its insertion point at the base of the distal phalanx of the great toe. The anterior tibial artery and vein and deep peroneal nerve run between the extensor hallucis longus and the tibialis anterior muscles. The muscle fibers of the extensor hallucis longus course inferiorly and medially, ending in a tendon that passes under the inferior extensor retinaculum, which prevents the muscle from bowstringing or subluxation.[2]

The principal function of the extensor hallucis longus is to extend the hallux and dorsiflex the foot at the ankle. Due to its origination on the fibula—the lateral bone of the anterior leg—and insertion on the tendon of the distal phalanx of the hallux, muscle contraction lifts the foot and the big toe upward toward the shin (dorsiflexion). This movement is critical to gait because it allows clearance of the foot off the ground during the swing phase. Consequently, damage or loss to the muscles or deep peroneal nerve, the innervation of the anterior compartment, can result in foot drop—loss of dorsiflexion—and a characteristic high-stepping gait.[3]

In addition to extending the hallux and dorsiflexing the foot at the ankle, the extensor hallucis longus has a role in weakly inverting the foot due to its insertion on the distal phalanx of the hallux—the most medial toe. Consequently, loss of the extensor hallucis longus can also result in weakness in foot inversion, although typically not clinically significant due to the strong action of the tibialis anterior in inverting the foot.

Embryology

The embryo's limb buds begin to form about five weeks after fertilization as the mesoderm migrates into the limb bud and forms a posterior condensation and an anterior condensation to eventually form the muscular and skeletal components of the lower limb.[4][5][6] The posterior condensation will develop into the extensor and abductor musculature of the lower limb, and the anterior condensation will form into the flexor and adductor musculature of the lower limb.[4][5][6]

Several factors influence the formation of the limb bud musculature, including retinoic acid, sonic hedgehog (SHH), HOX genes, apical ectodermal ridge (AER), and the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA). Retinoic acid is a global organizing gradient that initiates the production of transcription factors that specify regional differentiation and limb polarization. The apical ectodermal ridge (AER) produces fibroblast growth factor (Fgf), promoting the outgrowth of the limb buds by stimulating mitosis.[4][5][6] The specific fibroblast growth factor involved in hindlimb development is Fgf10, which gets stimulated by Tbx4.[7] SHH is produced by the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA), which promotes the organization of the limb bud along the anterior-posterior axis. SHH activates specific HOX genes – Hoxd-9, Hoxd-10, Hoxd-11, Hoxd-12, Hoxd-13 – which are important in limb polarization and regional specification.[4][5][6] These genes control patterning and, consequently, the morphology of the developing limb in the human embryo.[7] Errors in Hox gene expression can lead to malformations in the limbs.[7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The anterior tibial artery supplies the extensor hallucis longus muscle. The anterior tibial artery arises from the popliteal artery, which originates from the superficial femoral artery, a branch of the common femoral artery off the external iliac artery. As the superficial femoral artery passes through the adductor hiatus into the popliteal fossa, it becomes the popliteal artery. The popliteal artery then divides toward the distal end of the popliteal fossa to give rise to the anterior and posterior tibial arteries. The anterior tibial artery passes from the posterior popliteal fossa to the anterior leg through the interosseous membrane between the tibia and fibula. It continues down the anterior portion of the leg to supply all of the anterior compartment muscles, including the extensor hallucis longus, before terminating as the dorsalis pedis artery as it passes into the foot.

The lymphatic vessels of the lower limb divide into two major groups—superficial and deep vessels. The lower limb's superficial lymph vessels further subdivide into two groups: a medial group, which follows the greater saphenous vein, and a lateral group, which follows the small saphenous vein. There are also deep lymph vessels, including the anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and peroneal vessels, that follow the course of the corresponding arteries and veins. The lymph vessels of the lower limb drain into the popliteal, superficial inguinal, deep inguinal, external iliac, and lumbar or aortic lymph nodes.

Nerves

The deep peroneal nerve innervates the extensor hallucis longus. The deep peroneal nerve is one of the terminal branches of the common peroneal nerve, which originates from the sciatic nerve—the sciatic nerve branches at the apex of the popliteal fossa into the tibial and common peroneal nerves. The tibial nerve continues its course down the leg, posterior to the tibia supplying the deep muscles of the posterior leg. It terminates by dividing into two sensory branches, medial and lateral plantar nerves.[4] The common peroneal artery follows the medial border of the biceps femoris, running in a lateral and inferior direction, continuing over the head of the gastrocnemius.[4] The common peroneal nerve wraps around the neck of the fibula, passing between the attachments of the fibularis longus muscle to supply the lateral compartment of the leg.[4] It then divides and terminates into the superficial peroneal, which will supply the lateral compartment of the leg, and the deep peroneal, which will supply the anterior compartment of the leg, including the extensor hallucis longus.[4] The nerve roots of the deep peroneal artery are L4 to S1. Injury to the deep peroneal nerve can result in foot drop and, consequently, gait difficulty and a characteristic high step gait.

Physiologic Variants

The extensor hallucis longus muscle inserts into the dorsum of the base of the distal phalanx of the big toe. However, several variants exist that may possess one or more accessory tendinous slips that insert into other neighboring bones or tendons. These physiologic variants are clinically significant because the extensor hallucis longus muscle can be used in tendon transfer surgeries to correct conditions such as hallux varus, talipes equinovarus, and clawed hallux associated with a cavus foot.[8] The three most common insertion patterns are as follows[9]:

- Pattern 1 (65%): single tendinous insertion on the dorsal aspect of the base of the distal phalanx of the big toe

- Pattern 2 (26.7%): muscle-tendon terminated in two tendons

- Pattern 3 (8.3%): muscle terminated in three tendinous slips

Knowledge of the extensor hallucis variants is crucial for radiologists and surgeons to prevent adverse surgical events in tendon transfer surgeries.

Surgical Considerations

In trauma and other rare instances, the extensor hallucis longus tendon can be ruptured or damaged. In the event of a rupture or significant damage, the patient can present with a dropped hallux and loss of dorsiflexion, which can affect gait; this can be repaired surgically by the transfer of the first slip of the extensor digitorum longus and extensor hallucis brevis to the damaged extensor hallucis longus.[10] The extensor hallucis longus tendon itself can also be used in tendon transfer surgery to correct conditions such as hallux varus and talipes equinovarus.[9]

The anterior compartment of the leg is also the most common site for acute compartment syndrome.[4][11] When the pressure inside the anterior compartment increases, tissue perfusion can be compromised, leading to irreversible muscle and nerve damage – muscle necrosis. The most common causes of anterior compartment syndrome are trauma (fractures, crush injuries, contusions, gunshot wounds), tight casts or dressings, extravasation of IV infusion, burns, post-ischemic swelling, bleeding disorders, and arterial injury.[4][12] Recognition of compartment syndrome is essential to treating and preventing ischemia and necrosis of the neurovascular structures and muscles.[4] Patients with anterior compartment syndrome will often present with pain out of proportion to the clinical situation.[4][13] The physical exam findings of anterior compartment syndrome often include pain on palpation of the muscles involved, pain with passive stretching of the muscle (most sensitive test finding before the onset of ischemia), and firmness of the anterior compartment.[4][13] Compartment syndrome primarily affects the venous system; consequently, arterial pulses are usually intact.[4] Another pertinent finding for anterior compartment syndrome is a weakness of dorsiflexion. The definitive diagnosis of anterior compartment syndrome requires the measurement of compartmental pressures. A resting compartment pressure of greater than 30 mm Hg confirms the diagnosis of compartment syndrome.[4][13] In acute compartment syndrome, time is of the essence; if treated within 6 hours of ischemia, complete recovery is anticipated, whereas necrosis occurs after 6 hours of ischemia.[14] Definitive management of acute anterior compartment syndrome is a subcutaneous fasciotomy.[4]

Clinical Significance

The extensor hallucis longus is important in the dorsiflexion of the foot at the ankle and extension of the big toe. For this reason, it is tested during the physical exam to assess the range of motion and motor strength of the ankle and big toe. Weakened or absent motor strength can indicate muscle or nerve damage to the extensor hallucis longus and muscles of the anterior compartment of the leg or weakness from the L5 nerve root.

The extensor hallucis longus can also be involved in tendon rupture and tendonitis. The vast majority of extensor hallucis longus tendon injuries documented in the literature have been secondary to a laceration.[15] However, there is at least one known case in the literature of an atraumatic extensor hallucis longus tendon tear in a patient with no prior medical problems.[15] The extensor hallucis longus tendon can also be involved in tendonitis; this occurs when the tendon becomes overstressed resulting in inflammation and pain. The most common factors that cause tendonitis in the extensor muscles of the lower limb are excessive calf muscle tightness, overexertion during exercise, and falling of the foot arch.[16] In mild cases, extensor tendonitis is treatable with stretching and NSAIDs. In more severe cases, a walking boot can be used in addition to NSAIDs and stretching.

Another common injury to the anterior compartment of the lower leg is injury or damage to the deep peroneal nerve. In this case, the patient would present with an inability to dorsiflex the foot at the ankle and extend the toes. Injury to the deep peroneal nerve can severely impact gait resulting in a characteristic high stepping gait to compensate for the foot drop.

Lastly, the anterior compartment of the leg is the most common site for compartment syndrome. Compartment syndrome may occur acutely following blunt force injury or trauma or as a chronic, exertional syndrome commonly seen in athletes.[4][13] The muscle groups of the lower limb divide into compartments formed by strong, inflexible fascial membranes. Compartment syndrome occurs when increased pressure within one of these compartments compromises circulation and function to the tissues within that space.[4][13] The anterior compartment contains muscles that primarily dorsiflex the foot at the ankle, extend the toes and invert/evert the foot. These muscles are innervated and supplied by the deep peroneal nerve and anterior tibial artery, respectively. Increased pressure in the anterior compartment can cause paresthesias, weakness of muscle action, and pain with passive stretch of the muscles.[4][13] Compartment syndrome constitutes a medical emergency that requires a fasciotomy of the involved compartment.[4]