Introduction

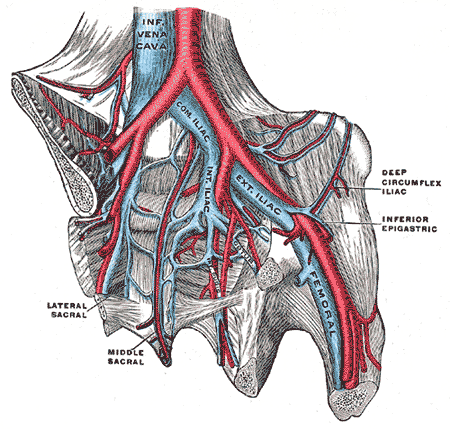

The common iliac artery bifurcates to give rise to the internal and external iliac arteries. The internal iliac artery supplies the pelvis, pelvic organs, reproductive organs, and the medial part of the thigh. The external iliac artery is the largest branch of the common iliac artery, and it forms the main blood supply to the lower extremity.

Structure and Function

The right and left external iliac arteries extend from the mid-pelvis to the inguinal ligament as the distal continuation of the common iliac arteries. The common iliac arteries arise from the aortic bifurcation and bifurcate into the external and internal iliac arteries anterior to the sacroiliac joint. The external iliac arteries begin at the common iliac bifurcation and take an anterior course along the medial border of the psoas major muscles before exiting the pelvic girdle posterior to the inguinal ligament. The exit point of the external iliac arteries is lateral to the insertion point of the inguinal ligament on the pubic tubercle, approximately one-third the distance from the pubic tubercle to the anterior superior iliac spine. Distal to the inguinal ligament, the external iliac artery becomes the common femoral artery.

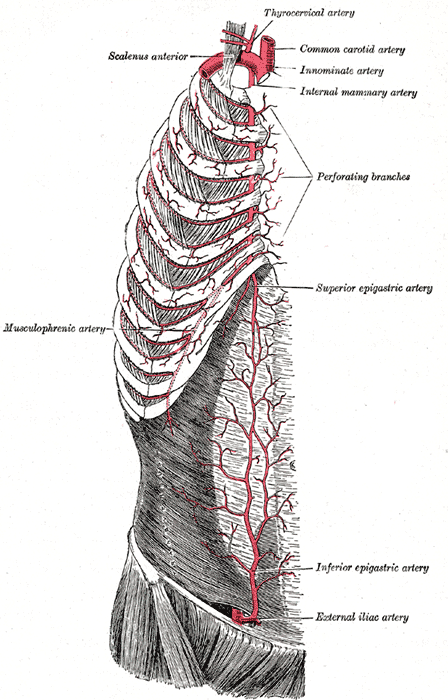

The external iliac arteries function as a short conduit for blood flow between the common iliac and common femoral arteries. Although they do not directly supply a muscle or tissue, the external iliac arteries give rise to two arterial branches that perfuse surrounding muscles: the inferior epigastric artery and the deep circumflex iliac artery. The inferior epigastric artery originates from the medial side of the distal external iliac artery. It travels superiorly along the posterior surface of the inferior rectus abdominis muscle. The deep circumflex iliac artery originates from the lateral side of the distal external iliac artery and travels laterally along the superior border of the iliac crest. The common femoral artery is the distal continuation of the external iliac artery as it passes posteriorly and inferiorly to the inguinal ligament.

Embryology

In the fourth week of fetal development, the umbilical arteries anastomose with dorsal intersegmental artery branches to become the dominant placental-aortic connection. This “new” umbilical artery becomes the common and internal iliac artery after birth interrupts the placental circulation. At five weeks of fetal development, the sciatic arteries and external iliac arteries arise from the same dorsal umbilical artery root. The two vessels then interconnect, and the sciatic artery regresses, forming the arteries of the lower extremity including the common femoral artery.[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood Supply

Blood enters the external iliac arteries via the common iliac arteries which arise from the bifurcation of the distal abdominal aorta. Branches of the external iliac arteries include the inferior epigastric arteries and deep circumflex iliac arteries. The majority of the blood flow continues through the lumen of the external iliac artery past the inguinal ligament and into the common femoral artery.

Lymphatics

Eight to ten external iliac lymph nodes surround the external iliac arteries in three groups: lateral, medial, and anterior. The lymph node afferents include deep lymphatics of the abdominal wall, adductor region of the thigh, glans penis, glans clitoris, membranous urethra, prostate, the fundus of the bladder, cervix, and upper portion of the vagina. The medial group of nodes contains medial, external, and obturator nodes. Obturator nodes have clinical significance as a common “landing zone” for prostatic cancer metastasis.[2]

Muscles

As arteries that conduct blood flow from the pelvis to the lower extremities, the external iliac arteries do not terminate in capillary beds. Two branches of the external iliac artery are the inferior epigastric and deep circumflex iliac arteries. The inferior epigastric artery supplies the rectus abdominis muscle, whereas the deep circumflex artery supplies the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles. The deep circumflex iliac artery also supplies blood to the iliac fossa and internal oblique muscles.

Physiologic Variants

The incidence of external iliac artery agenesis remains unknown since the condition only manifests itself when symptomatic. In the congenital absence of an external iliac artery, compensatory blood flow patterns provide arterial perfusion to the lower extremity. The most common anatomy observed in these cases involves the distal internal iliac artery being continuous with the common femoral artery. Descriptions of an external iliac artery with an unusual, deep pelvic course may also represent a form of agenesis.[3]

Arterial coiling occurs most frequently in the carotid arteries as a result of excessive elongation related to aging. Coiling rarely occurs in peripheral arteries such as the external iliac. Corkscrew external iliac arteries have been reported.[4] Symptoms are uncommon and can range from claudication to distal embolization of thrombus from the twisted, narrow arterial lumen.

Corona Mortis is a vascular connection between the obturator and external iliac or inferior epigastric vessels that occurs in 9.8% of patients.[5] This vascular anomaly can be arterial, venous, or both. A Corona Mortis blood vessel usually crosses the superior pubic ramus where it is vulnerable to injury.

Surgical Considerations

The diameter and disease status of the external iliac artery plays an important role in planning an endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Endovascular access to the abdominal aorta usually involves passing guide wires and sheaths from the common femoral artery, through the external and common iliac arteries, and into the aorta. An extremely small caliber, tortuous, or calcified external iliac artery may necessitate alternative vascular access techniques or conversion to open surgery.

Corona Mortis, a vascular connection between the internal and external iliac vessels, can be injured during surgery. Inadvertent transection of the Corona Mortis can cause the vessel to retract inferiorly or through the obturator foramen, severely compromising vascular control for hemostasis. Pelvic osteotomies using the medial approach, as well as acetabular fracture procedures using the ilioinguinal approach, pose the highest risk for severing a Corona Mortis vessel.[6]

Surgical or endovascular manipulation can cause dissection of the external iliac artery.[7] An acute arterial dissection involves a tear in the intimal lining, allowing blood to flow between the muscular layers of the vessel. This double-lumen flow can cause an acute thrombosis that acutely occludes the artery or degenerates into an aneurysm over a more extended period.

Clinical Significance

Stenosis or occlusion of the iliofemoral arterial system restricts the flow of blood to the lower extremity. Depending on the patient's activity level, those with arterial occlusive disease of the external iliac artery may have no symptoms or pain in the lower extremity muscles with walking. The most common disease-causing external iliac artery occlusive disease is atherosclerosis. Fibromuscular dysplasia can also cause external iliac artery stenosis and should be considered in symptomatic patients who do not have cardiovascular risk factors.

Endofibrosis of the external iliac artery causes stenosis leading to leg pain and activity limitations in some avid cyclists. Histologically an endofibrotic lesion has a loose connective tissue matrix and a medium to high cell density, in contradistinction to an atherosclerotic lesion.[8] Macrophages are more likely to be present in atherosclerotic lesions, further differentiating the two lesions histologically.

Most kidney transplants involve an anastomosis between the end of the donor's renal artery and the side of the recipient’s external iliac artery. Although the internal or external iliac artery can be used to perfuse a donor's kidney, the use of the external iliac had a lower incidence of post-operative erectile dysfunction in a 2015 study.[9] An acute external iliac artery dissection that occurs during transplant surgery can restrict or occlude blood flow causing transplant kidney dysfunction or failure.

A persistent sciatic artery represents a congenital vascular anomaly that can involve aplasia of the external iliac artery. A persistent sciatic artery is classified as complete or incomplete. In patients with a complete persistent sciatic artery, the sciatic artery is the primary blood supply to the lower extremity and the external iliac artery is absent. This anatomy results in the confusing exam finding of an absent femoral pulse and a palpable popliteal pulse. An incomplete persistent sciatic artery partially communicates with a hypoplastic common femoral artery. Limb threatening complications of persistent sciatic artery include arterial thrombosis and aneurysm formation.[10]

Isolated iliac artery aneurysms are rare compared to abdominal aortic aneurysms and combined aortoiliac artery aneurysms. Case series in the literature suggests that less than 10% of all isolated iliac artery aneurysms occur in the external iliac artery.[11]