Continuing Education Activity

Venous access can be obtained through the cannulation of peripheral veins, such as the antecubital or saphenous vein, or central veins, such as the internal jugular or femoral vein. The insertion of a central venous line is potentially life-saving in that it allows for the rapid administration of high volumes of isotonic fluids and medications that would otherwise be caustic to peripheral veins. In most instances, central venous access with ultrasound guidance is considered the standard of care. This activity reviews the indications, contraindications, and techniques involved in performing femoral vein cannulation and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of patients undergoing this procedure.

Objectives:

- Identify the indications for femoral vein cannulation.

- Describe the technique involved in performing femoral vein cannulation.

- Outline the complications of femoral vein cannulation.

- Explain the importance of improving coordination amongst the interprofessional team to enhance care for patients undergoing femoral vein cannulation.

Introduction

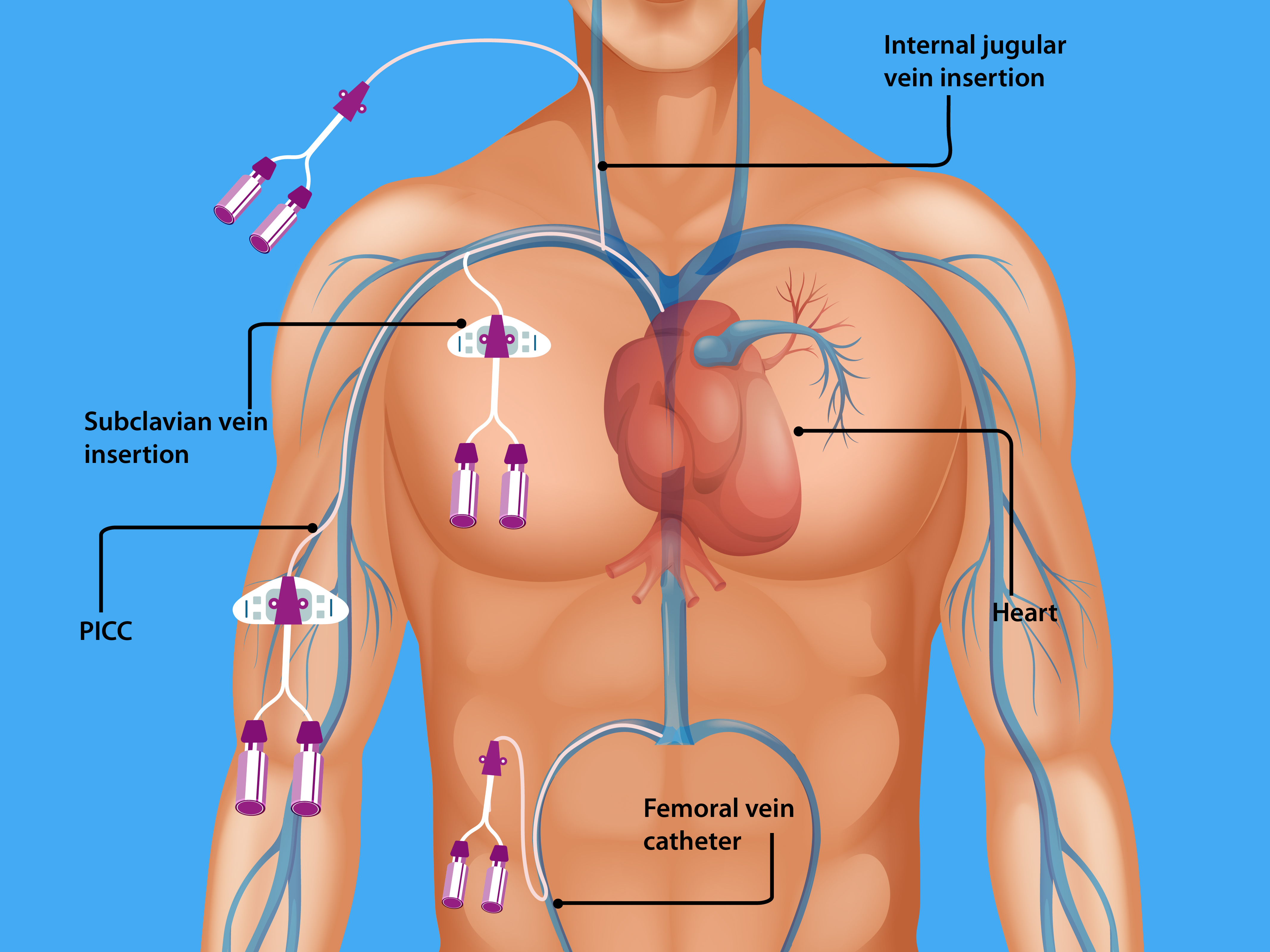

Venous access can be obtained through the cannulation of peripheral (e.g., antecubital vein, saphenous vein) or central veins (e.g., internal jugular vein, femoral vein). The insertion of a central venous line is potentially life-saving as, in emergent situations, it allows rapid administration of high-volume isotonic fluids and medications that would otherwise be caustic to peripheral veins. This article will focus on central venous access via the femoral vein. However, there are some aspects applicable to other central venous access sites.[1][2][3][4]

Anatomy and Physiology

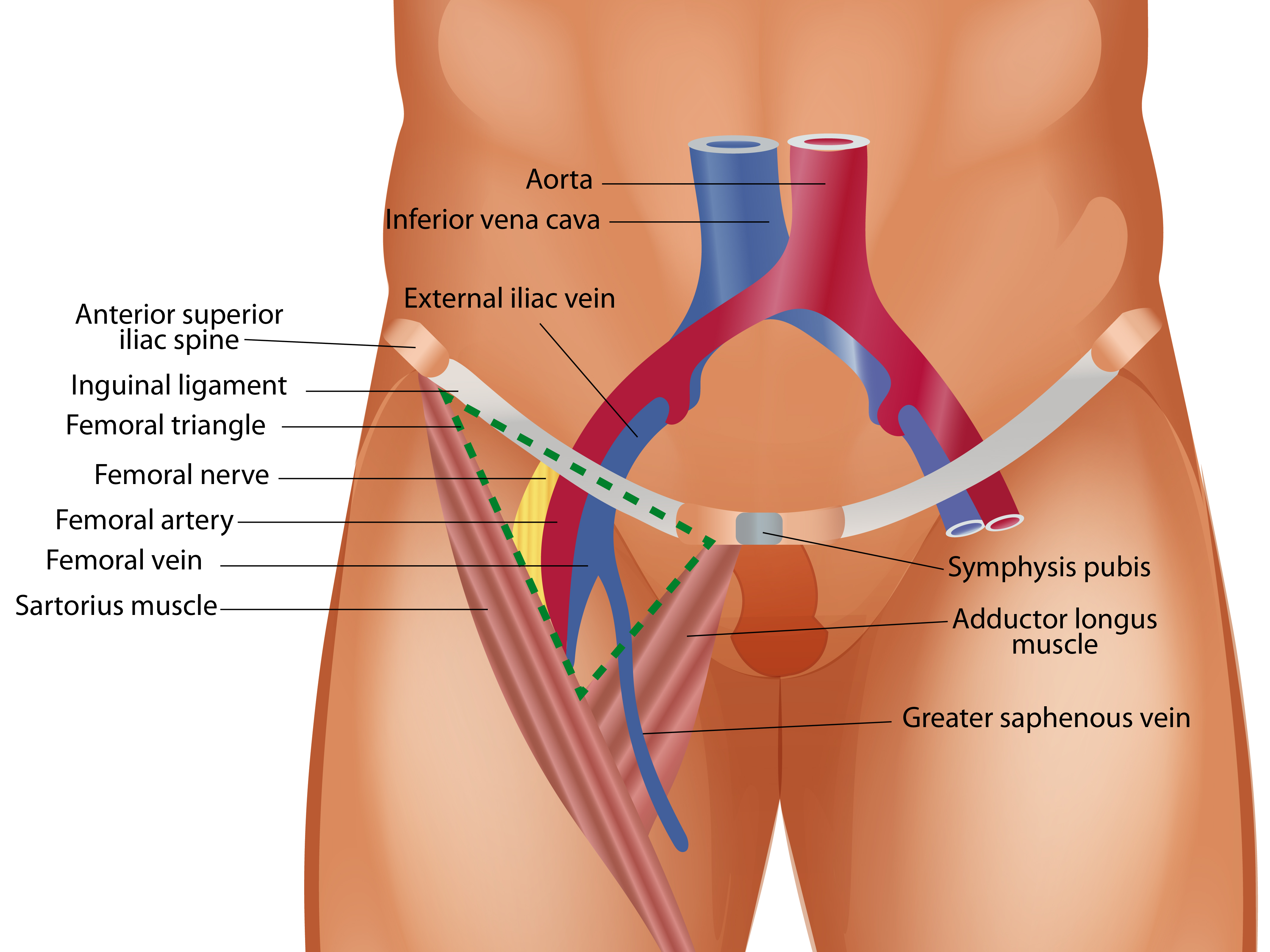

In the leg, venous drainage flows proximally from the popliteal vein to the superficial femoral vein. Continuing proximally, the superficial femoral vein is joined by the deep femoral vein in the upper thigh, becoming the common femoral vein. The great saphenous vein joins the common femoral vein near the inguinal ligament. The common femoral vein becomes the external iliac vein superior to the inguinal ligament. The internal iliac vein drains into the external iliac vein, becoming the common iliac vein, and the common iliac veins join to become the inferior vena cava (IVC).

The common femoral vein is the ideal to puncture when performing central venous access at the femoral site. The common femoral vein lies within the “femoral triangle” in the inguinal-femoral region. This region is bordered by the inguinal ligament superiorly, the adductor longus medially, and the sartorius muscle laterally. Understanding the relationship of structures within the inguinal-femoral area is essential, which can be remembered using the mnemonic “NAVEL.” Moving laterally to medially, (N) femoral nerve, (A) femoral artery, (V) femoral vein, (E) space, (L) lymphatics. For the remainder of this article, the term femoral vein refers to the common femoral vein unless otherwise specified.

When obtaining central venous access in the femoral vein, the key anatomical landmarks to identify in the inguinal-femoral region are the inguinal ligament and the femoral artery pulsation. In most instances, central venous access with ultrasound guidance is considered the standard of care. Nevertheless, understanding and using anatomical landmarks are equally essential and lead to increased success when combined with ultrasound guidance.[5]

Indications

In general, the indications for central venous access include the following:

- Peripheral access is unobtainable

- Medication to be infused is known to induce peripheral phlebitis

- High-volume fluid and parenteral nutrition administration is required

- Emergency resuscitation is warranted[6]

- Monitoring of central venous oxygen saturation and central venous pressure is indicated

- Frequent blood sampling needs to be performed

- Access is necessary to perform hemodialysis, hemofiltration, or apheresis.

Note that the indications mentioned above are not absolute. The balance of risks and benefits when performing the procedure should be considered for each patient. The indication for line placement also prompts the proceduralist to consider additional factors.

Contraindications

Potential contraindications to central venous access via the femoral vein are the following:

- Thrombosis

- Skin infection at the site of needle puncture

- Trauma

- Distorted anatomy

- Coagulopathy

Since this procedure has life-saving potential, the contraindications noted above are relative. Additionally, if these issues are encountered at the femoral site, an alternative site (e.g., internal jugular vein, subclavian vein) should be considered.

Equipment

Although institutional variability may exist, the following is standard equipment needed to perform central venous access. Additionally, some vendors have pre-assembled kits that may contain several of these items.

- Central venous catheter

- Introducer a needle and a slip-tip syringe

- Guidewire

- Dilator

- Scalpel

- Gauze (4x4)

- Hubs for access ports on the catheter

- Normal saline for flushing catheter

- Chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine solution for topical cleaning

- Topical anesthesia (e.g., 1% lidocaine)

- 25-gauge needle and a syringe for the administration of topical anesthesia

- Facemask and hair cap

- Sterile gown and gloves

- Sterile drape that is long enough to cover the patient from head to toe

- Needle holder and silk sutures

- If using ultrasound guidance: ultrasound, sterile ultrasound probe cover, sterile and non-sterile ultrasound gel

- For line dressing: facemask, sterile gloves, and chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine solution for topical cleaning if sterile field not maintained; anti-microbial disc, occlusive dressing and covers the entire insertion site and is also clear to allow for visualization of the insertion site.

Personnel

A sterilized individual to assist with opening packaging and handing sterile equipment in a manner that maintains the sterile field is generally helpful. Additionally, a separate individual to provide sedation/analgesia and monitor effects is ideal and safest for the patient. Lastly, a second sterilized individual may be required to assist with ultrasonography, depending on the comfort and/or experience of the proceduralist.

Preparation

Provide informed consent to the patient by explaining the risks and benefits of the procedure, as well as the alternatives to the procedure

Choose an appropriately sized central venous catheter for the patient. This decision may be influenced by the clinical indication, patient size, and vessel caliber. Consider the following:

- Catheter size in French (F) (e.g., 4F, 7F)

- Catheter length (in centimeters)

- Number of lumens required

Perform a procedural “timeout” to confirm that the correct procedure is being performed on the valid patient and the correct side of the patient (i.e., right or left side)

Position the patient:

- The patient can be placed in a reverse Trendelenburg position to engorge the femoral vein, which could potentially increase the vessel’s caliber

- The patient’s leg can be positioned in one of three ways: frog-leg position, external rotation at the hip with full leg extension, or abduction of a fully extended leg with external rotation at the hip.

- Proceduralist washes hands with soap and water.

- Proceduralist dons sterile personal protective equipment (PPE) (i.e., cap, facemask, sterile gown, and gloves)

- Sterile prepping of the skin at the site of insertion with chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine solution

- Place a sterile drape over the patient ensuring coverage from head to toe

- If ultrasound guidance is utilized, insert non-sterile ultrasound gel into the clean probe cover and place the ultrasound probe into the cover. The sterile ultrasound gel will be used in the sterile field to assist with the visualization

- Administer local anesthetic as an effort to minimize the use of systemic analgesia/sedation

- Flush all lumens of the central venous catheter with normal saline.

Technique or Treatment

Employ the "landmark technique" to isolate the location of the femoral vein for puncture. There are several methods to do this, and some examples are:

- Use your index finger to locate the arterial pulsation along the inguinal ligament at the midpoint between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic symphysis. Then move 1 cm to 2 cm inferior to this position as the needle puncture must be performed below the inguinal ligament. Next, move 1 cm to 2 cm as the vein lies medial to the artery.

- Use your index and middle fingers to locate the distal and proximal pulsations of the femoral artery. Just medial to your fingertips should be the general course of the femoral vein. Hence, it would be best if you punctured the medial to your index finger in a medial direction to your middle finger.

At the desired location and using the slip-tip syringe-introducer needle complex, puncture the skin at a 30 to 45-degree angle to the skin.

- Using ultrasound guidance, information is provided on the relationship of vessels to each other and other surrounding structures. Additionally, vessel depth, caliber, and patency can also be assessed. These findings should be integrated with landmark findings to assist in choosing an ideal puncture site, entry angle, and needle direction.

- Pull back on the plunger of the syringe while advancing the syringe-needle complex. Aspiration of blood into the syringe indicates entry into a vessel. The color of blood aspirated does not help distinguish between arterial and venous blood. If resistance is met, retract the syringe-needle complex slowly, as the needle may have gone through the vessel. If blood is still not aspirated, pull back the syringe-needle complex just short of coming out of the skin, and reconsider needle direction and angle.

- When blood is easily aspirated, stabilize the needle's hub and remove the syringe. A steady dripping of blood is to be expected. The presence of pulsatile blood flow should concern the practitioner for arterial puncture. Insert the guidewire into the needle hub and advance slowly. The guidewire should move quickly and only be inserted at a length that is 2 cm to 3 cm longer than the introducer needle. The proceduralist should never let go of the guidewire to avoid mishaps.

- While maintaining the guidewire position, slowly remove the needle.

- Using the scalpel, incise the skin at the puncture site while avoiding the guidewire.

- Insert the dilator over the guidewire and advance slowly through the incised puncture site. In general, the entire length of the dilator does not need to be inserted. The dilator only needs to be advanced to a depth that allows it to pass through the skin and enter the vessel slightly.

- Remove the dilator while maintaining the guidewire position, and then advance the central venous catheter over the guidewire.

- Attempt to aspirate blood from each access port of the catheter to ensure patency and then place hubs on each access port.

- Using the needle holder and silk sutures, suture the catheter in place.

- Place the antimicrobial disc over the catheter insertion site and apply the dressing.

- Confirm catheter placement via blood gas, x-ray, and pressure transduction.

- Perform documentation of the procedure in the medical record.

Complications

Complications from central venous access can be classified into early and late complications. Again, some of these are not specific to the femoral site and can occur with insertion at other central venous access sites.[7][8][9][10]

Early

- Arterial puncture could result in the formation of a hematoma

- Hematoma formation could also result from routine placement

- Bladder puncture. At our institution, we catheterize or insert a foley catheter before placement of a femoral central line

- Hemorrhage

- Catheter fragment resulting in a guidewire embolism

- Cardiac dysrhythmias, particularly from high-lying central lines

Late

- Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI)

- Phlebitis

- Thrombosis

- Erosion/perforation

The following are not complications, per se, but can lead to complications:

- Uncooperative patient

- Lack of experience/supervision

| Early complications |

Late complications |

| Arterial puncture |

Central line-associated bloodstream infection |

| Hematoma |

Phlebitis |

| Bladder puncture |

Thrombosis |

| Guidewire embolism |

Erosion |

| cardiac dysrrhthymias |

Perforation |

Clinical Significance

CLABSIs are the most common complication of central venous catheter placement. CLABSIs are a source of significant morbidity and mortality and increased healthcare costs. Most of the equipment, preparation, and technique described above have been incorporated into bundled practices and checklists that have been shown to reduce the incidence of CLABSIs. In adults, the femoral site is avoided due to evidence demonstrating a higher risk of bloodstream infection than other sites. However, this has not been shown in children, and the femoral site is preferred in this population due to ease of access. Lastly, long-term central venous access, such as PICCs, has also been associated with a lower risk of bloodstream infections.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A clinician usually performs femoral vein cannulation, but the nursing staff monitors the line. In general, femoral vein cannulation is not preferred because the groin site is challenging to keep clean, and patient ambulation is difficult. These lines should not be kept for more than 24 to 48 hours. Nurses should monitor the site for bleeding, infection, and hematoma. The only benefit of a femoral line is that, unlike a subclavian or IJ central line, the risk of a pneumothorax is non-existent. Interprofessional care coordination between nurses and clinicians is crucial; the nurse should promptly report any concerns, including possible infection, so corrective measures can be implemented if necessary. Any problems should also be noted in the patient's permanent medical record. This interprofessional approach will enable optimal outcomes with the fewest adverse events. [Level 5]