Introduction

The fetal circulation system is distinctly different from adult circulation. This intricate system allows the fetus to receive oxygenated blood and nutrients from the placenta. It is comprised of the blood vessels in the placenta and the umbilical cord, which contains two umbilical arteries and one umbilical vein. Fetal circulation bypasses the lungs via a shunt known as the ductus arteriosus; the liver is also bypassed via the ductus venosus, and blood can travel from the right atrium to the left atrium via the foramen ovale. Normal fetal heart rate is between 110 and 160 beats per minute. When compared to adults, fetuses have decreased ventricular filling and reduced contractility.[1]

Fetal circulation undergoes a rapid transition after birth to accommodate extra-uterine life. Human understanding of fetal circulation originated from fetal sheep, but ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) during the fetal period now provide detailed information.[2] There are distinct differences in fetal circulation that, if not appropriately formed, can lead to childhood or adult diseases.

Issues of Concern

With advancing medical technology, babies are more viable at fewer weeks of gestation than ever before — immature hearts transitioning to newborn circulation has-life long effects. Adults born preterm were studied and found to have increased cardiac muscle mass, reduced chamber length, and impaired function. These impairments are more profound in those born profoundly premature; they were found to have 50% more ventricular cardiac muscle mass than those born at term. These patients are at increased risk of ischemic heart disease and heart failure.[1] Another area of concern is when certain shunts fail to close after birth; the baby can be born with congenital heart defects that present with varying signs and symptoms; this is discussed further below.

Cellular Level

The yolk sac initiates erythropoiesis until the liver can take over at five weeks gestation, and then the bone marrow finally contributes at six months gestation. The relative hypoxia, when compared to the mother, activates hypoxia-inducible factor-1 to stimulate erythropoietin production in the kidneys, which improves the capacity of fetal blood for oxygen. Fetal hemoglobin also possesses a higher affinity for oxygen when compared to maternal hemoglobin. However, fetal tissue has adapted ways to unload the oxygen from the higher affinity hemoglobin in the fetal tissue by creating an acidic environment. By the age of 4 to 6 months, the baby will have an adult hemoglobin level and no fetal hemoglobin. After birth, erythropoiesis will also slow.[2][3][4]

Development

The fetal heart initiates at 22 days; this indicates the initiation of fetal circulation. Gas exchange initially occurs in the yolk sac until the placenta entirely takes over. This transition occurs around ten weeks of gestation. Maternal oxygenated blood mixes with placental blood, which is low in oxygen, before heading out to the fetus. Due to this mixing, the fetus is relatively hypoxic compared to maternal arterial blood.[2]

As the baby is born, the cardiovascular system undergoes a quick, drastic change. With its first breath, the baby's pulmonary vascular resistance substantially drops, which is in response to the oxygen now present in the lungs and the physical act of breathing. With the umbilical cord clamping after birth, the systemic vascular resistance increases, helping the blood flow toward the lungs. The ductus arteriosus has a left-to-right flow within 10 minutes. The smooth muscle in the ductus arteriosus responds to the oxygen by increasing calcium channel activity, causing constriction and, ultimately, shunt closure. The increased systemic resistance also raises the pressure in the left atrium to be higher than the right atrium, and this causes the foramen ovale to close.[2]

Organ Systems Involved

The mother's uterus fosters the environment for fetal growth and placental vitality. Every organ system is involved in the process of fetal circulation because as the fetus grows and develops, it needs oxygen and nutrients that the blood supplies. The fetal blood will reach every aspect of the growing fetus except for the liver and lungs, which are bypassed. However, the fetal arterial system will receive waste products that originated from those organs.

Function

The fetal circulatory system provides the fetus with nutrients and oxygen while removing waste products and carbon dioxide from fetal circulation.

Mechanism

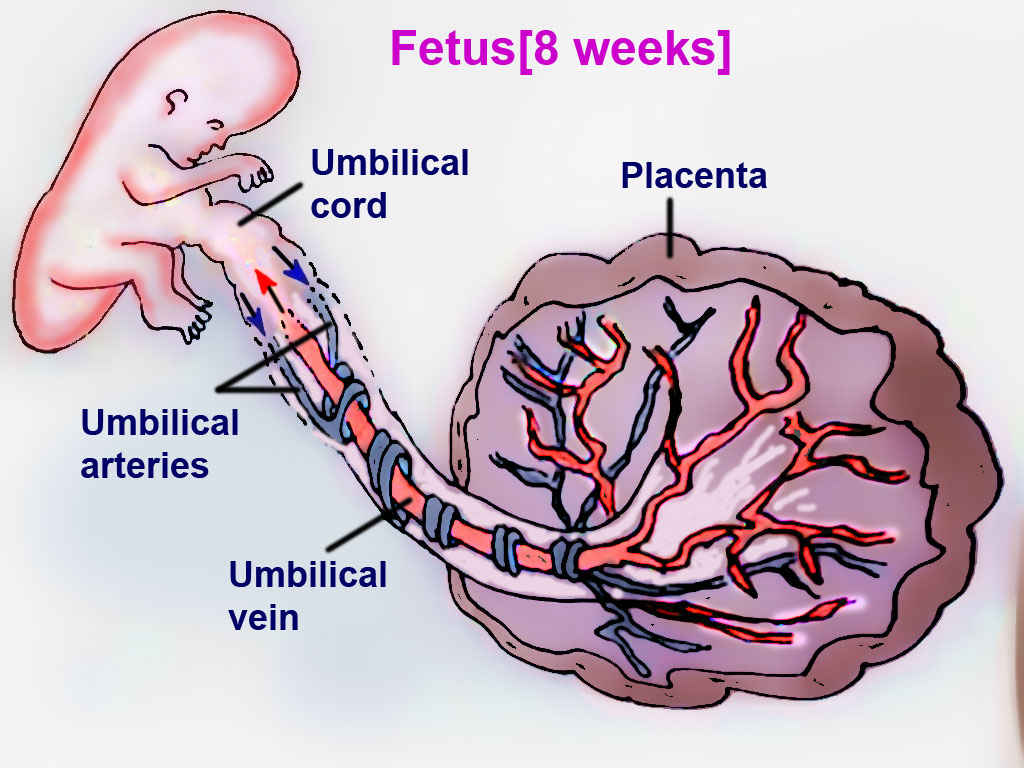

The placenta connects the maternal and fetal circulatory systems. The placenta provides oxygen and nutrients from the mother to the growing fetus. Also, it removes metabolic wastes and carbon dioxide from the fetus via the blood vessels in the umbilical cord. The umbilical cord develops from the placenta and is attached to the fetus.[5] Oxygenated blood from the mother in the placenta flows through the umbilical vein to be distributed partially to the fetal hepatic circulation but mostly into the inferior vena cava (IVC), bypassing the liver via the ductus venosus, with an estimated oxygen saturation of 70 to 80%.

From the IVC, blood travels through the right atrium of the heart to be directed across a shunt into the left atrium. There is greater pressure in the right atrium compared to the left atrium in fetal circulation; therefore, most of the oxygenated blood is shunted from the right atrium to the left atrium through an opening called the foramen ovale, whereas a mixture of oxygenated blood from the IVC and deoxygenated blood from the superior vena cava (SVC) becomes partially oxygenated blood in the right atrium. As a result, the estimated oxygen saturation of the left atrium is 65% compared to the right atrium, which is only 55%.

Once the oxygenated blood reaches the left atrium, it travels through the left ventricle into the coronary arteries and aorta, which branches to provide the most oxygenated blood to the brain before a shunt from the pulmonary artery, called the ductus arteriosus, allows partially oxygenated blood to be combined to the blood supply that will then flow to the systemic circulation with an estimated oxygen saturation of 60%. The partially oxygenated blood in the right atrium, mentioned above, can also enter the right ventricle and then the pulmonary artery. Because there is high resistance to blood flow in the lungs, the blood is shunted from the pulmonary artery into the aorta via the ductus arteriosus, mostly bypassing the lungs.

Blood then enters the systemic circulation, and the deoxygenated blood, with an estimated oxygen saturation of 40%, is recycled back to the placenta via the umbilical arteries to be oxygenated again by the mother.[2]

Related Testing

Tests to detect congenital heart defects can be completed during pregnancy. A fetal echocardiogram can visualize the fetal heart as early as 16 weeks of pregnancy. Some defects only manifest following birth. In these cases, evaluation consists of a thorough history and physical examination, an echocardiogram, and potentially a cardiac catheterization. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is a tool to measure the oxygenation of fetal tissues noninvasively, and physicians can then calculate blood flow and oxygen delivery.[2] Other tests can be conducted depending on the presenting signs and symptoms.

In the tetralogy of Fallot, a boot-shaped heart due to right ventricular hypertrophy may be present on a chest X-ray.

Rib notching may present on chest X-rays in patients with coarctation of the aorta because the intercostal arteries enlarge as the patient grows older.

An echocardiogram will show any structural or valve abnormalities in the fetal or newborn heart.

Pathophysiology

In fetal circulation, the right side of the heart has higher pressures than the left side of the heart. This pressure difference allows the shunts to remain open. In postnatal circulation, when the baby takes its first breath, pulmonary resistance decreases, and blood flow through the placenta ceases. Blood commences flowing through the lungs, and the pressure on the left side becomes higher than on the right. As a result, the shunts mentioned above close.

Congenital heart defects arise when shunts fail to close after birth. Abnormalities in the anatomy of the heart can also alter the proper flow of blood. These defects can be cyanotic or acyanotic. Cyanotic heart defects are typically from right-to-left shunts in blood after birth. The baby can appear blue at birth, with deoxygenated blood bypassing the lungs and entering the systemic circulation. Examples of cyanotic heart defects are tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), transposition of the great arteries (TGA), persistent truncus arteriosus, tricuspid atresia, and total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR). Acyanotic heart defects are typically left-to-right shunts in blood after birth. Because the left side contains oxygenated blood, no deoxygenated blood enters the systemic circulation. Instead, some oxygenated blood goes to the right side of the heart and travels through the lungs again. As a result, the baby does not initially appear blue at birth. Examples of acyanotic heart defects are atrial septal defect (ASD), ventricular septal defect (VSD), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), and patent foramen ovale (PFO).

However, the shunt can reverse later in life if the left-to-right shunt goes uncorrected. With the left-to-right shunt, there can be a severe overload of the right heart due to increased blood flow, causing an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance, which causes pulmonary hypertension. Eventually, the right ventricle hypertrophies, and the pressure on the right side of the heart becomes more significant than on the left side. As a result, the shunt reverses and becomes right-to-left. Deoxygenated blood starts entering systemic circulation, and the baby can present with cyanosis. This switching of flow from left-to-right to right-to-left is known as Eisenmenger syndrome.

Developing endocardial cushions is essential in understanding why certain cardiac defects develop. The endocardial cushions contribute to the emergence of the atrial and ventricular septa, the mitral and tricuspid valves, the conotruncal septum, and the atrioventricular septa. When there is an endocardial cushion defect, it can cause cardiac malformations like ASD and VSD. These defects are also common in patients with trisomy 21 and fetal alcohol syndrome. ASDs arise when there is a hole in the atrial septum after birth. An ASD leads to communication between the right and left atria. The primum type of ASD is due to inadequate development of endocardial cushions and is seen less often than the secundum type. VSD arises when there is a hole in the ventricular septum after birth. A VSD leads to communication between the right and left ventricles.

Conotruncal septal defects are accountable for persistent truncus arteriosus, TGA, and TOF. In persistent truncus arteriosus, a single arterial trunk originates from both the right and left ventricles. It is not able to divide into the aorta and pulmonary artery distally. Because of a failure of neural crest cell migration, the conotruncal ridges are not able to form, resulting in this defect, which results in the deoxygenated blood from the right ventricle mixing with the oxygenated blood from the left ventricle, causing cyanosis. In TGA, the aorta and pulmonary artery switch locations. The aorta, in this case, originates from the right ventricle, and the pulmonary artery arises from the left ventricle. As a result, two independent blood circuits do not mix due to the conotruncal septum failing to spiral during development. Deoxygenated blood returns to the right side of the heart, travels through the aorta, and goes out to the body.

On the other hand, oxygenated blood returns to the left side of the heart from the lungs and then travels through the pulmonary artery to go back to the lungs. A shunt is needed for survival in this case due to the lack of oxygenated blood being delivered to the body. In TOF, there is an anterior displacement of the conotruncal septum. It is characterized by pulmonary stenosis, a VSD, an overriding aorta, and hypertrophy of the right ventricle. The pulmonary stenosis forces the deoxygenated blood to travel through the VSD from the right side to the left side, leading to right ventricular hypertrophy. Because of the deoxygenated blood crossing over into systemic circulation, the baby presents with early cyanosis.

Vascular malformations may also result in congenital defects. Coarctation of the aorta develops when there is constriction of the aortic arch distal to where the subclavian artery branches off. Pre-ductal indicates that the constriction is before the ductus arteriosus, and post-ductal indicates that the constriction is after the ductus arteriosus. In pre-ductal coarctation of the aorta, deoxygenated blood travels from the right atrium to the right ventricle and then through the pulmonary artery. Because a PDA is present, the deoxygenated blood crosses over to the aorta after the point of constriction. In post-ductal coarctation of the aorta, deoxygenated blood travels from the right atrium to the right ventricle and then through the pulmonary artery. Because there is no PDA present, the deoxygenated blood does not cross over to the left side.

Clinical Significance

The clinical presentation of babies with ASD is related to the size of the hole. Patients are often asymptomatic and are only detected when hearing a murmur. However, a patient with a large ASD could present with heart failure, failure to thrive, or recurrent lung infections. The murmur associated with ASD is a fixed splitting of S2 due to A2 occurring before P2, which is due to the increase in right atrial and right ventricular volumes, which ultimately increase flow through the pulmonic valve, delaying closure.[6][7][8]

The clinical presentation of babies with VSD also depends on the defect's size. Small VSDs are often asymptomatic. Larger VSDs with significant left-to-right shunting may cause failure to thrive and congestive heart failure because the heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the body's demands. A holosystolic murmur was auscultated at the left lower sternal border.

On physical examination of babies born with PDA, patients have a continuous machine-like murmur, loudest at S2. It is best auscultated in the left infraclavicular area and associated with congenital rubella or prematurity.

In TOF, a child commonly presents with "tet spells." These spells mean that cyanosis may develop when a child is agitated. Upon physical exam, the patient will have a blue tint to their lips and around their mouth, their skin will be damp or warm, and breathing will be rapid.[9]

A child with pre-ductal coarctation of the aorta may present with differential cyanosis. There will only be lower extremity cyanosis because deoxygenated blood is not entering the branches of the aorta that go to the upper extremities. In post-ductal coarctation of the aorta, a child will not present with cyanosis because a PDA is not present. A child with coarctation of the aorta may also present with high blood pressure in the upper extremities because of the high pressure before constriction and low blood pressure in the lower extremities after the point of constriction.

Treatment

Prostaglandins from the placenta keep the shunts in the fetus open. During birth, the shunts usually close due to the loss of prostaglandins from placental separation and increased oxygen due to respiration. However, in the management of PDA, NSAIDs like indomethacin may be given to close the shunt because it blocks the production of prostaglandins.

TGA is incompatible with life, except when there is another heart defect that allows blood to mix. Prostaglandins may be given to permit the oxygenated blood and deoxygenated blood to mix by keeping the ductus arteriosus open.

In TOF, squatting may improve symptoms. Squatting kinks the femoral arteries, increasing systemic vascular resistance. As a result, the pressure of the left heart is greater than that of the right heart, reversing the shunt. However, early surgical correction is the recommendation.