Continuing Education Activity

Food allergy is defined as an immune reaction to proteins in the food and can be immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated or non-IgE-mediated. IgE-mediated food allergy is a worldwide health problem that affects millions of persons and numerous aspects of a person's life. Allergic reactions secondary to food ingestion are responsible for a variety of symptoms involving the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and respiratory tract. This activity reviews the pathophysiology and presentation of food allergies and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of food allergies.

- Review the presentation of a patient with food allergies.

- Summarize the treatment options for food allergies.

- Explain modalities to improve care coordination among interprofessional team members in order to improve outcomes for patients affected by food allergies.

Introduction

Food allergy is defined as an immune reaction to proteins in the food and can be immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated or non–IgE-mediated. IgE-mediated food allergy is a worldwide health problem that affects millions of persons and numerous aspects of a person’s life. Allergic reactions secondary to food ingestion are responsible for a variety of symptoms involving the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and respiratory tract. Prevalence rates are uncertain, but the incidence appears to have increased over the past three decades, primarily in countries with a Western lifestyle.[1][2][3]

Any food can cause allergy but overall only a few foods account for the vast majority of allergies. This includes milk, eggs, peanuts, shellfish, wheat, and nuts. In the last few years, many cases of near-fatal reactions following food ingestion have been reported. It should be noted that reactions that do not involve the immune system are not food allergies (eg milk intolerance).

Etiology

Food allergy can have 2 etiology depending on the mechanism of disease: IgE-mediated or type I hypersensitivity and other immunologically non-IgE mediated reactions.[4][5]

The food allergens are usually water-soluble glycoproteins that are resistant to breakdown and are easily transported across the mucosal surface in the intestine.

Risk factors for severe food allergies or anaphylaxis include:

- Asthma

- Prior episodes of anaphylaxis

- Delay in the use of epinephrine

Epidemiology

About 6% of children experience food allergic reactions in the first three years of life, including approximately 2.5% with cow’s milk allergy, 1.5% with egg allergy, and 1% with peanut allergy. Studies have shown that peanut allergy prevalence increased over the past decade. Most children tend to outgrow milk and egg allergies by school-age. In contrast, children with peanut, nut, or seafood allergy retain their allergy for life.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

In predisposed persons exposed to certain allergens, IgE antibodies specific for food are formed that bind to basophils, macrophages, mast cells, and dendritic cells on Fc epsilon receptors. Once food allergens enter the mucosal barriers and reach cell-bound IgE antibodies, these mediators are released and cause smooth muscle to contract, vasodilation, and mucus secretion, which result in symptoms of immediate hypersensitivity (allergy). Activated mast cells and macrophages that attract and activate eosinophils and lymphocytes release cytokines. This leads to prolonged inflammation, affecting the skin (flushing, angioedema, or urticaria), respiratory tract (rhinorrhea, nasal pruritus with nasal congestion, sneezing, dyspnea, laryngeal edema, wheezing), gastrointestinal tract (nausea, oral pruritus, vomiting, angioedema, abdominal pain, diarrhea), and cardiovascular system (hypotension, loss of consciousness, dysrhythmias) as per the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics.[8][7]

About 40% of patients with food allerges also develop chronic atopic dermatitis; when the food is withdrawan, the atopic dermatitis also improves.

Celiac disease is due to an immune response to dietary gluten. In addition, in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis, elimination of gluten from the diet improves the skin symptoms.

History and Physical

Clinical Manifestations

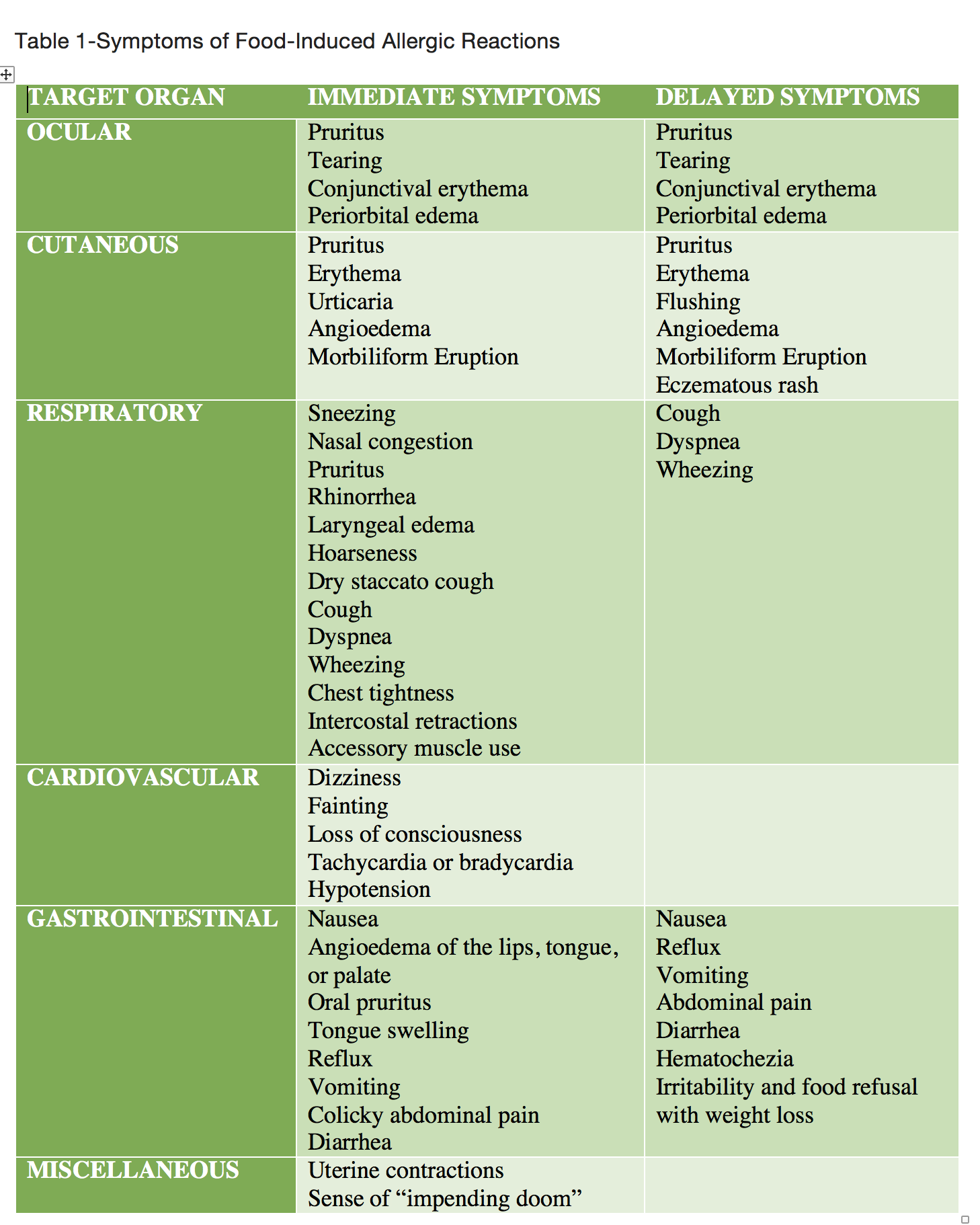

According to the predominant target organ and immune mechanism, it is most useful to subdivide food hypersensitivity disorders (Table 1).

Table 1- Symptoms of Food-Induced Allergic Reactions

Gastrointestinal

Food allergies that cause gastrointestinal manifestations are often the initial form of allergy to affect infants and young children, causing irritability, vomiting or “spitting-up,” diarrhea, and poor weight gain. There are three main entities related to food allergies associated with gastrointestinal symptoms

- Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES): these patients can present with emesis one to three hours after feeding, and constant exposure might result in abdominal distention, bloody diarrhea, anemia, and faltering weight and are provoked by cow’s milk or soy protein-based formulas.

- Food protein-induced proctocolitis is known to cause blood-streaked stools in otherwise healthy infants in the first few months of life and is associated with breastfed infants.

- Food protein-induced enteropathy is associated with steatorrhea and poor weight gain in the first several months of life.

Skin

- Atopic dermatitis, also known as eczema, is linked to asthma and allergic rhinitis, and about 30% of children with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis have food allergies.

- Acute urticaria and angioedema are one of the most common symptoms of food allergic reactions and tend to have very rapid onset after the responsible allergen is ingested. Most likely foods include egg, milk, peanuts, and nuts, but sesame and poppy seeds and fruits such as kiwi have been linked.

- Perioral dermatitis is benign and is regularly a contact dermatitis caused by substances in toothpaste, gum, lipstick, or medications. These tend to resolve spontaneously.

Respiratory

- Respiratory food allergies are uncommon as isolated symptoms. Wheezing occurs in approximately 25% of IgE-mediated food allergic reactions, but only approximately 10% of asthmatic patients have food-induced respiratory symptoms.

Evaluation

When suspecting a food allergy, the diagnostic approach begins with a careful medical history and physical examination. The history is particularly key in assessing a particular acute reaction such as systemic anaphylaxis, but also for attempting to establish which food was involved and what allergic mechanism is likely. A diet diary often can be helpful to supplement a medical history, especially in chronic disorders, as it identifies the specific food causing symptoms. A focused physical is also important, as an examination of the patient may provide signs consistent with an allergic reaction or disorder often associated with food allergy.[9][10]

When the history does not reveal the causative food allergen, allergy testing can be performed. For IgE-mediated disorders, skin prick tests (SPTs) provide a rapid means to detect sensitization to a specific food but has advantages and disadvantages as a positive test suggests the possibility of reactivity to a specific food, around 60% of positive tests do not reflect symptomatic food allergy. In contrast, a negative skin-prick establishes the absence of an IgE-mediated reaction. Therefore more definitive tests, such as quantitative IgE tests or food elimination and challenge, are often necessary to establish a diagnosis of food allergy.

Serum tests to determine food-specific IgE antibodies (e.g., RASTs) offer additional modality to assess IgE-mediated food allergy. Increasingly higher concentrations of food-specific IgE correlate with an increased likelihood of a clinical reaction. When a patient has a food-specific IgE level exceeding the predictive (diagnostic) values, he or she is more than 95% likely to experience an allergic reaction.

On the other hand, a provocative oral challenge is needed to establish whether a patient has hypersensitivity to a particular food, and the double-blind, placebo-controlled challenge is the gold standard for food allergy diagnosis. Suspect foods should be eliminated for 7 to 14 days before challenge, and longer in some non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal disorders, to increase the likelihood of a non-equivocal food challenge result. Also, medications that could interfere with the evaluation of food-induced symptoms (e.g., antihistamines and b-adrenergic bronchodilators) must be discontinued. If symptoms remain unchanged despite appropriate elimination diets, it is unlikely that food allergy is accountable for the child’s disorder. If the blinded challenge result is negative, it must be confirmed using an open and supervised feeding of a typical serving of the food to rule out a false-negative challenge result that can occur in approximately 1% to 3% of the cases.

Treatment / Management

Once the diagnosis of food hypersensitivity is established, the only proven therapy remains elimination of the offending allergen, with the absence of a cure. Parents and children affected with food allergy require extensive education, including specific instruction on understanding food labels, restaurant meals, and risky behaviors leading to unexpected reactions. Patients at risk for anaphylaxis must be trained to recognize initial symptoms promptly and should be instructed on the proper use of auto-injectable epinephrine and have epinephrine and antihistamines accessible at all times.[11][12][13]

Patients with food allergy with asthma or a past history of severe reaction or reaction to peanuts, nuts, seeds, or seafood should be given self-injectable epinephrine and a written emergency plan for treatment of an unintentional ingestion. Clinical tolerance develops to most food allergens over time, except for peanuts, nuts, and seafood. Children with low levels of peanut-specific IgE should be reexamined to determine whether they have outgrown their allergy.

Prevention of Food Allergy

Currently, the recommendations are to introduce complementary solid foods, such as egg, peanut products, fish, wheat, and other allergenic foods one at a time after four to six months of age when breastfeeding, as there is no need to avoid or delay their introduction.

Differential Diagnosis

- Factitious disorder

- Esophagitis and esophageal motility disorders

- Giardiasis

- GERD

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Bacterial or viral gastroenteritis

- Lactose intolerance

- Whipple disease

Prognosis

Over time, most children outgrow or become tolerant of food allergens to eggs, milk, wheat, and soy. However, allergies to nuts and shellfish are more long-standing. Close to 20% of children have a resolution of their food allergy by school age. The non-IgE mediated food allergies resolve within the first year of life. Unfortunately, sporadic cases of fatal anaphylactic reactions still continue to occur.

Complications

- Anaphylaxis

- Respiratory distress

- Cardiac arrest

Consultations

- Allergist

- Pulmonologist

- Pediatrician

- Dietitian

- Gastroenterologist

Pearls and Other Issues

Food allergic reactions are the most common cause of anaphylaxis seen in hospital emergency departments in the United States. Anaphylaxis is a potentially fatal allergic reaction that occurs rapidly and involves multiple systems including cutaneous, cardiovascular, respiratory, and gastrointestinal symptom.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Food allergies have become a problem in society. Even though the risk of anaphylaxis is rare, there is hysteria over certain foods in schools, hotels, and in many public places. Parents and travelers have become demanding about foods, often resulting in major league arguments. The key is to educate the patient and caregiver. Managing food allergies requires an interprofessional team dedicated to the care of children.

All patients with a documented food allergy should be educated by the nurse to carry a self-injectable device that contains epinephrine. This device needs to be stored properly. The school nurse should provide the student with education on how and when to use the device. Older patients may be educated on the benefits of carrying an antihistamine in syrup or chewable form. More important, the pharmacist should educate the caregiver on how to use the epinephrine containing devices and how to identify an allergic reaction. The key is to avoid the allergen. A dietary consult is recommended so that the patient and the caregiver can be taught to identify food allergens and eliminate them from the diet. Parents should be educated about reading labels on foods and how to identify allergens. [2][14](Level V)

Outcomes

The majority of infants and young children develop tolerance to their food allergies with time. Most children outgrow their allergies to eggs, milk, and soy within 3-5 years. However, there are also reports that more than 50% of children will continue to have food allergies that persist to puberty. However, over time, even these children will develop tolerance to their allergies by the end of the second decade of life. Children who have non-IgE mediated food allergies such as enterocolitis usually have a cessation of their disorder within the first few years after birth. Unfortunately, children with eosinophilic esophagitis may have symptoms that continue to persist. Severe anaphylactic reactions with food allergies are rare but do occur. The fatalities are usually seen in school children and the foods implicated include shellfish, peanuts, and fish. [15][16](Level V)