Introduction

Some organs, such as the brain, the eye, and the kidney, contain tissues that utilize glucose as their preferred or sole metabolic fuel source. During a prolonged fast or vigorous exercise, glycogen stores become depleted, and glucose must be synthesized de novo in order to maintain blood glucose levels. Gluconeogenesis is the pathway by which glucose is formed from non-hexose precursors such as glycerol, lactate, pyruvate, and glucogenic amino acids.[1]

Gluconeogenesis is essentially the reversal of glycolysis. However, to bypass the three highly exergonic (and essentially irreversible) steps of glycolysis, gluconeogenesis utilizes four unique enzymes.[1] The enzymes unique to gluconeogenesis are pyruvate carboxylase, PEP carboxykinase, fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase, and glucose 6-phosphatase. Because these enzymes are not present in all cell types, gluconeogenesis can only occur in specific tissues. In humans, gluconeogenesis takes place primarily in the liver and, to a lesser extent, the renal cortex.[2]

Cellular Level

Although gluconeogenesis can be broadly considered the reversal of glycolysis, it is not an identical pathway running in the opposite direction. Several enzymes catalyze reactions with small changes in free-energy, meaning they are easily reversible and function well in both pathways. However, three reactions of glycolysis are highly exergonic, resulting in largely negative free-energy changes that are irreversible and must be bypassed by different enzymes. The enzymes unique to gluconeogenesis are pyruvate carboxylase, PEP carboxykinase, fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase, and glucose 6-phosphatase.

Starting from pyruvate, the reactions of gluconeogenesis are as follows:

- In the mitochondrion, pyruvate is carboxylated to form oxaloacetate via the enzyme pyruvate carboxylase. Pyruvate carboxylase requires ATP as an activating molecule as well as biotin as a coenzyme. This reaction is unique to gluconeogenesis and is the first of two steps required to bypass the irreversible reaction catalyzed by the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase.

- In the cytosol, oxaloacetate is decarboxylated and rearranged to form phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) via the enzyme PEP carboxykinase. PEP carboxykinase requires GTP as an activating molecule and magnesium ion as a cofactor. This reaction is unique to gluconeogenesis and is the second of two steps required to bypass the irreversible reaction catalyzed by the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase.

- PEP is hydrated to form 2-phosphoglycerate via the enzyme enolase.

- 2-phosphoglycerate converts to 3-phosphoglycerate via the enzyme phosphoglycerate mutase.

- 3-phosphoglycerate is phosphorylated via the enzyme phosphoglycerate kinase to form 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate. This reaction requires ATP as an activating molecule.

- 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate is reduced to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate via the enzyme glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. NADH is the electron donor.

- Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate is isomerized to form dihydroxyacetone phosphate via the enzyme triose phosphate isomerase.

- Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate are combined to form fructose 1,6-bisphosphate via the enzyme aldolase.

- Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate is dephosphorylated to form fructose 6-phosphate via the enzyme fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase or FBPase-1. This reaction is unique to gluconeogenesis and bypasses the irreversible reaction catalyzed by the glycolytic enzyme phosphofructokinase-1.

- Fructose 6-phosphate converts to glucose 6-phosphate via phosphohexose isomerase.

- Glucose 6-phosphate is dephosphorylated by glucose 6-phosphatase to form glucose, which is free to enter the bloodstream. This reaction is unique to gluconeogenesis and bypasses the irreversible reaction catalyzed by the glycolytic enzyme hexokinase.

The major substrates of gluconeogenesis are lactate, glycerol, and glucogenic amino acids.

- Lactate is a product of anaerobic glycolysis. When oxygen is limited (such as during vigorous exercise or in low perfusion states) cells must perform anaerobic glycolysis to produce ATP. Cells that lack mitochondria (e.g., erythrocytes) cannot perform oxidative phosphorylation, and as a result rely strictly on anaerobic glycolysis to meet energy demands. Lactate generated from anaerobic glycolysis gets shunted to the liver, where it can be converted back to glucose through gluconeogenesis. Glucose gets released into the bloodstream, where it travels back to erythrocytes and exercising the skeletal muscle to be broken down again by anaerobic glycolysis, forming lactate. This process is called the Cori cycle.[2]

- Glycerol comes from adipose tissue. The breakdown of triacylglycerols in adipose tissue yields free fatty acids and glycerol molecules, the latter of which can circulate freely in the bloodstream until it reaches the liver[3]. Glycerol is then phosphorylated by the hepatic enzyme glycerol kinase to yield glycerol phosphate. Next, the enzyme glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase oxidizes glycerol phosphate to yield dihydroxyacetone phosphate, a glycolytic intermediate.

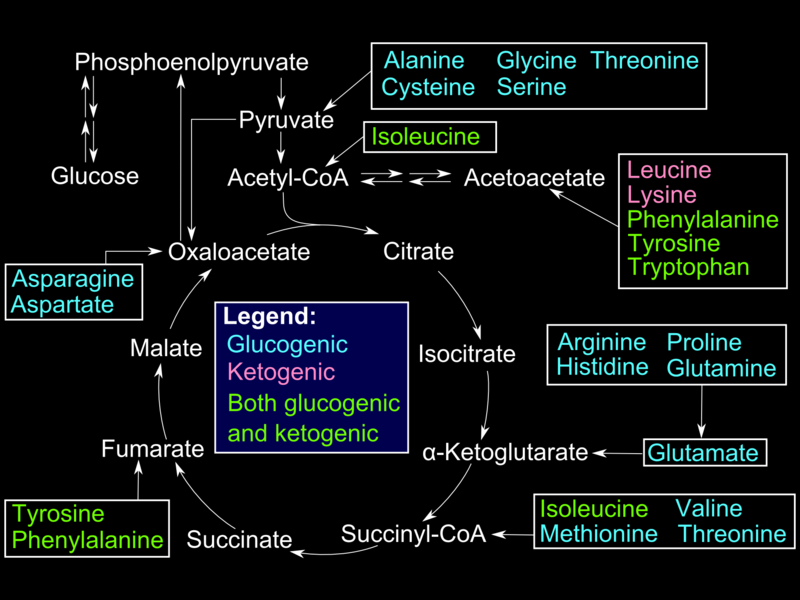

- Glucogenic amino acids enter gluconeogenesis via the citric acid cycle. Glucogenic amino acids are catabolized into citric acid cycle metabolites such as alpha-ketoglutarate, succinyl CoA, and fumarate. Through the citric acid cycle, these alpha-ketoacids converts to oxaloacetate, the substrate for the gluconeogenic enzyme PEP carboxykinase.

Due to the highly endergonic nature of gluconeogenesis, its reactions are regulated at a variety of levels. The bulk of regulation occurs through alterations in circulating glucagon levels and availability of gluconeogenic substrates. However, fluctuations in catecholamines, growth hormone, and cortisol levels also play a role.[4][5]

- Glucagon is produced by pancreatic alpha cells in response to falling blood glucose levels. It regulates glucose production by altering the activity of both glycolytic and gluconeogenic enzymes. In response to glucagon, fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase activity is upregulated while its glycolytic counterpart, phosphofructokinase-1, is suppressed.[6] Moreover, glucagon binds to an extracellular G protein-coupled receptor that results in the activation of adenylate cyclase and a subsequent increase in the concentration of cAMP.[7] cAMP activates cAMP-dependent protein kinase, which then phosphorylates and inactivates the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase. Pyruvate kinase is the enzyme responsible for converting PEP to pyruvate, one of the irreversible reactions of glycolysis. Lastly, glucagon upregulates expression of the gene encoding PEP-carboxykinase, further increasing PEP concentrations and favoring glucose production.[7]

- Insulin is a potent inhibitor of gluconeogenesis.[8] During a fast, falling insulin levels have a permissive effect on gluconeogenesis. Moreover, a decrease in insulin allows for the catabolism of fat and protein leading to increased gluconeogenic substrate availability.[4]

Organ Systems Involved

During the first 18 to 24 hours of a fast, the vast majority of gluconeogenesis occurs in the liver. Following prolonged periods of starvation, however, the kidneys adapt to generate as much as 20% of total glucose produced. Only the liver and kidney can release free glucose from glucose 6-phosphate; other tissues lack the enzyme glucose 6-phosphatase.[1][2]

Function

The purpose of gluconeogenesis is to maintain blood glucose levels during a fast. In the human body, some tissues rely almost exclusively on glucose as a metabolic fuel source. The brain, for example, requires approximately 120 g of glucose in 24 hours. While the brain is also capable of utilizing ketone bodies as an alternative fuel source, the testes, renal medulla, and erythrocytes all rely exclusively on glucose breakdown through glycolysis. For these tissues to function correctly, a steady influx of glucose into the bloodstream is essential. Hepatic glycogen stores are depleted following a 24-hour fast, after which time gluconeogenesis functions to synthesize glucose de novo from non-hexose precursors and maintain blood glucose levels.[1][2]

Pathophysiology

In the absence of glucose-6-phosphatase, gluconeogenesis is impaired and this precipitates fasting hypoglycemia. This event can occur in Von Gierke's disease when this enzyme is deficient. Von Gierke disease takes an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Glycogenolysis is also limited in the absence of glucose-6-phosphatase because normally when glycogen is broken down to glucose-1-phosphate moiety, it is then converted to glucose-6-phosphate which requires glucose-6-phosphatase to convert it to usable glucose. So in the absence of this enzyme, gluconeogenesis, and glycogenolysis are both impaired. In addition to fasting hypoglycemia, other associated irregularities include hyperkalemia, hyperuricemia, and increased lactate levels. [9]

Clinical Significance

Treating Hyperglycemia in Diabetes

Diabetes is either the result of impaired insulin production or decreased insulin sensitivity. In addition to stimulating glucose uptake from the bloodstream, insulin is also a potent inhibitor of gluconeogenesis. Without adequate insulin production or the ability to respond to insulin properly, gluconeogenesis occurs at an unusually rapid rate, exacerbating hyperglycemia in the diabetic patient.[1]

Metformin, the first-line agent for the management of type 2 diabetes, has been shown to suppress hepatic gluconeogenesis through a variety of mechanisms. Metformin activates AMPK, which in turn inhibits hepatic lipogenesis and increases insulin sensitivity. AMPK activation also leads to increased cAMP breakdown, further inhibiting gluconeogenesis.[1][10]

Metformin also appears to directly inhibit glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, leading to an increase in NADH levels.[1][10] If concentrations of NADH are high enough, the lactate dehydrogenase reaction will favor the formation of lactate over the formation of pyruvate, and lactate will begin to accumulate. Gluconeogenesis is inhibited without the oxidation of lactate to pyruvate.

At high doses, metformin also inhibits complex I of the electron transport chain, impairing ATP production necessary for highly endergonic processes (like gluconeogenesis) to take place.[1]

Hypoglycemia as a Result of Ethanol Consumption

Ethanol cannot be eliminated from the human body without changes. To excrete ethanol, it must first be oxidized to form acetaldehyde by the liver enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase, which utilizes NAD+ as an electron acceptor. Next, acetaldehyde must be further oxidized to form acetate (a molecule readily excreted by the body). This reaction, catalyzed by aldehyde dehydrogenase, also requires NAD+ as an electron acceptor. Thus, the metabolism of ethanol results in a significant accumulation of NADH.[11]

If concentrations of NADH are high enough, the lactate dehydrogenase reaction will favor the formation of lactate over the formation of pyruvate, and lactate will begin to accumulate. Without the oxidation of lactate to pyruvate, gluconeogenesis is inhibited. As a consequence, heavy ethanol consumption can lead to both lactic acidosis and hypoglycemia.[11]

Hypoglycemia in the Preterm Infant

Preterm infants are at a particularly high risk of developing hypoglycemia. Neonates of low birth weight have limited glycogen and fat stores, but also express gluconeogenic enzymes at sub-optimal levels. As such, preterm infants can deplete their energy stores quickly without mounting a proper counter-regulatory response.[4]