Introduction

Glucose is a 6-carbon structure with the chemical formula C6H12O6. It is a ubiquitous source of energy for every organism in the world and is essential to fuel both aerobic and anaerobic cellular respiration. Glucose often enters the body in isometric forms such as galactose and fructose (monosaccharides), lactose and sucrose (disaccharides), or starch (polysaccharide). Our body stores excess glucose as glycogen (a polymer of glucose), which becomes liberated in times of fasting. Glucose is also derivable from products of fat and protein break-down through the process of gluconeogenesis. Considering how vital glucose is for homeostasis, it is no surprise that there are a plethora of sources for it.

Once glucose is in the body, it travels through the blood and to energy-requiring tissues. There, glucose is broken down in a series of biochemical reactions releasing energy in the form of ATP. The ATP derived from these processes is used to fuel virtually every energy-requiring process in the body. In eukaryotes, most energy derives from aerobic (oxygen-requiring) processes, which start with a molecule of glucose. The glucose is broken down first through the anaerobic process of glycolysis, leading to the production of some ATP and pyruvate end-product. In anaerobic conditions, pyruvate converts to lactate through reduction. In aerobic conditions, the pyruvate can enter the citric acid cycle to yield energy-rich electron carriers that help produce ATP at the electron transport chain (ETC).[1]

Cellular Level

Glucose reserves get stored as the polymer glycogen in humans. Glycogen is present in the highest concentrations in the liver and muscle tissues. The regulation of glycogen, and thus glucose, is controlled primarily through the peptide hormones insulin and glucagon. Both of these hormones are produced in the pancreatic Islet of Langerhans, glucagon in from alpha-cells, and insulin from beta-cells. There exists a balance between these two hormones depending on the body's metabolic state (fasting or energy-rich), with insulin in higher concentrations during energy-rich states and glucagon during fasting. Through a process of signaling cascades regulated by these hormones, glycogen is catabolized liberating glucose (promoted by glucagon in times of fasting) or synthesized further consuming excess glucose (facilitated by insulin in times of energy-richness). Insulin and glucagon (among other hormones) also control the transport of glucose in and out of cells by altering the expression of one type of glucose transporter, GLUT4.[1][2]

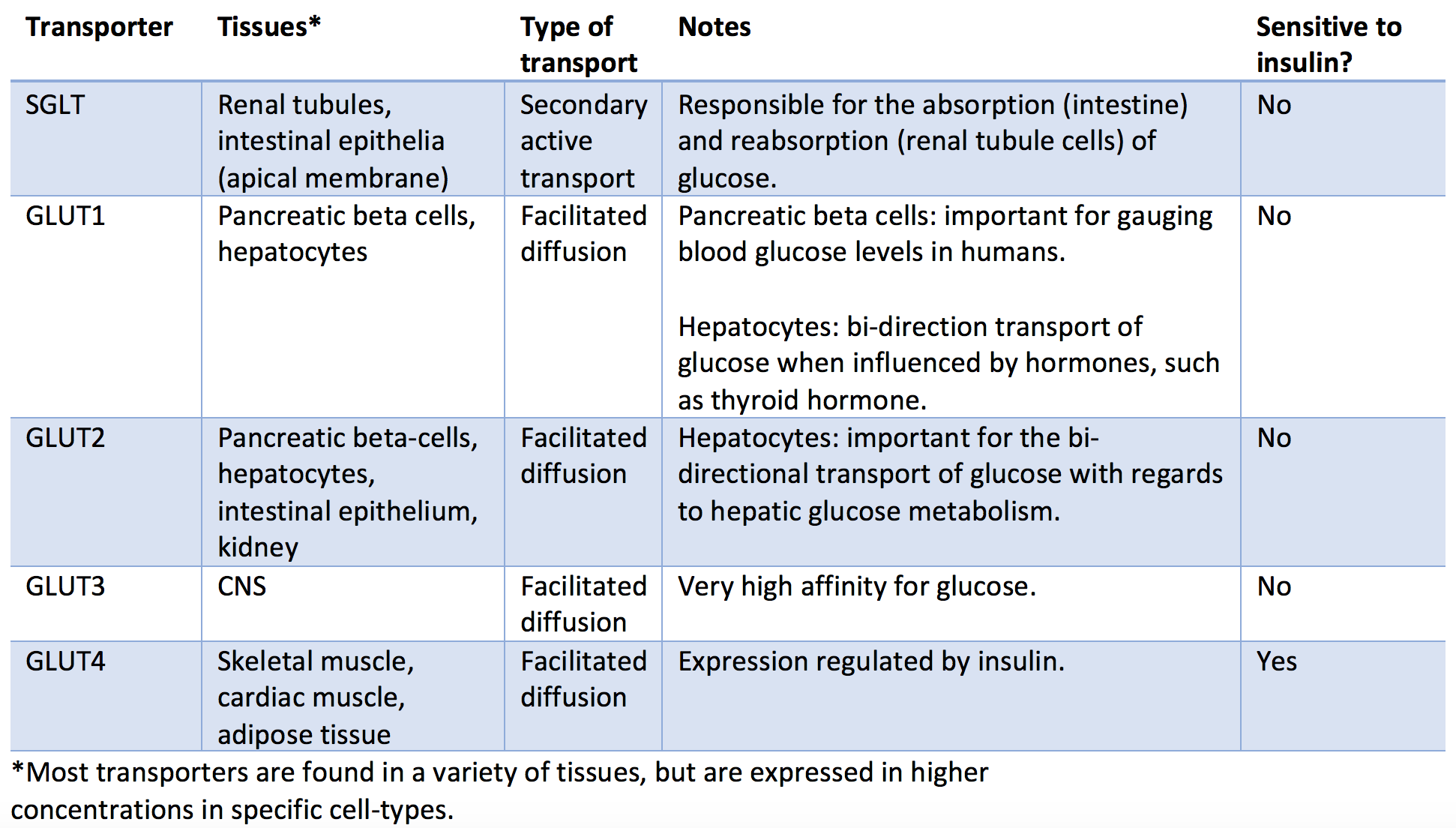

There are several types of glucose transporters in the human body with differential expression varying by tissue type. These transporters differentiate into two main categories: sodium-dependent transporters (SGLTs) and sodium-independent transporters (GLUT). The sodium-dependent transporters rely on the active transport of sodium across the cell membrane, which then diffuses down its concentration gradient along with a molecule of glucose (secondary active transport). The sodium-independent transporters do not rely on sodium and transport glucose using facilitated diffusion. Of the sodium-independent transporters, only GLUT4's expression is affected by insulin and glucagon. Below are listed the most important classes of glucose transporters and their characteristics.

- SGLT: Found primarily in the renal tubules and intestinal epithelia, SGLTs are important for glucose reabsorption and absorption, respectively. This transporter works through secondary active transport as it requires ATP to actively pump sodium out of the cell and into the lumen, which then facilitates cotransport of glucose as sodium passively travels across the cell wall down its concentration gradient.

- GLUT1: Found primarily in the pancreatic beta-cells, red blood cells, and hepatocytes. This bi-directional transporter is essential for glucose sensing by the pancreas, an important aspect of the feedback mechanism in controlling blood glucose with endogenous insulin.

- GLUT2: Found primarily in hepatocytes, pancreatic beta-cells, intestinal epithelium, and renal tubular cells. This bi-directional transporter is important for regulating glucose metabolism in the liver.

- GLUT3: Found primarily in the CNS. This transporter has a very high affinity for glucose, consistent with the brain's increased metabolic demands.

- GLUT4: Found primarily in skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, adipose tissue, and brain tissue. This transporter gets stored in cytoplasmic vesicles (inactive), which will amalgamate with the cell membrane when stimulated by insulin. These transporters will experience a 10 to 20-fold increase in density in times of energy-excess upon the release of insulin with the net effect of a decrease in blood glucose (glucose will more readily enter the cells that have GLUT4 on their surface).[3][4]

Central Role of Glucose in Carbohydrate Metabolism

The final products of the carbohydrate digestion in the alimentary tract are almost entirely glucose, fructose, and galactose, and the glucose comprises 80% of the end product. After absorption from the alimentary canal, much of the fructose and almost all of the galactose is rapidly converted into glucose in the liver. Therefore only a small quantity of fructose and galactose is present in the circulating blood. Thus glucose becomes the final common pathway for the transport of all of the carbohydrates to the tissue cells.

In liver cells, appropriate enzymes are available to promote interconversions among the monosaccharides- glucose, fructose, and galactose. The dynamics of the enzymes are as such when the liver releases the monosaccharides, the final product always glucose. The reason is that the hepatocytes contain a large amount of glucose phosphatase. Therefore the glucose-6-phosphate can be degraded to the glucose and the phosphate, and the glucose can be transported through the liver cell membrane back into the blood.

Organ Systems Involved

Glucose has a vital role in every organ system. However, there are select organs that play a crucial role in glucose regulation.

Liver

The liver is an important organ with regards to maintaining appropriate blood glucose levels. Glycogen, the multibranched polysaccharide of glucose in humans, is how glucose gets stored by the body and mostly found in the liver and skeletal muscle. Try to think of glycogen as the body's short-term storage of glucose (while triglycerides in adipose tissues serve as the long-term storage). Glucose is liberated from glycogen under the influence of glucagon and fasting conditions, raising blood glucose. Glucose is added to glycogen under the control of insulin and energy-rich conditions, lowering blood glucose.

Pancreas

The pancreas releases the hormones primarily responsible for the control of blood glucose levels. Through increasing glucose concentration within the beta-cell, insulin release occurs, which in turn acts to lower blood glucose through several mechanisms, which are detailed below. Through lower glucose levels and lower insulin levels (directly influenced by low glucose levels), alpha-cells of the pancreas will release glucagon, which in turn acts to raise blood-glucose through several mechanisms that are detailed below. Somatostatin is also released from delta-cells of the pancreas and has a net effect of decreasing blood glucose levels.[5][6][7]

Adrenal Gland

The adrenal gland subdivides into the cortex and the medulla, both of which play roles in glucose homeostasis. The adrenal cortex releases glucocorticoids, which will raise blood glucose levels through mechanisms described below, the most potent and abundant being cortisol. The adrenal medulla releases epinephrine, which also increases blood glucose levels through mechanisms described below.[8]

Thyroid Gland

The thyroid gland is responsible for the production and release of thyroxine. Thyroxine has widespread effects on almost every tissue of the body, one of which being an increase in blood glucose levels through mechanisms described below.[9]

Anterior Pituitary Gland

The anterior pituitary gland is responsible for the release of both ACTH and growth hormone, which increases blood glucose levels through mechanisms described below.[10]

Hormones

There are many hormones involved with glucose homeostasis. The mechanisms in which they act to modulate glucose are essential; however, at the very least, it is essential to understand the net effect that each hormone has on glucose levels. One trick is to remember which ones lower glucose levels: insulin (primarily) and somatostatin. The others increase glucose levels.

- Insulin: decreases blood glucose through increased expression of GLUT4, increased expression of glycogen synthase, inactivation of phosphorylase kinase (thus decreasing gluconeogenesis), and decreasing the expression of rate-limiting enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis.

- Glucagon: increases blood glucose through increased glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis.

- Somatostatin: decreases blood glucose levels through local suppression of glucagon release and suppression of gastrin and pituitary tropic hormones. This hormone also decreases insulin release; however, its net effect is a decrease in blood glucose levels.

- Cortisol: increases blood glucose levels via the stimulation of gluconeogenesis and through antagonism of insulin.

- Epinephrine: increases blood glucose levels through glycogenolysis (glucose liberation from glycogen) and increased fatty acid release from adipose tissues, which can then be catabolized and enter gluconeogenesis.

- Thyroxine: increases blood glucose levels through glycogenolysis and increased absorption in the intestine.

- Growth hormone: promotes gluconeogenesis, inhibits liver uptake of glucose, stimulates thyroid hormone, inhibits insulin.

- ACTH: stimulates cortisol release from adrenal glands, stimulates the release of fatty acids from adipose tissue, which can then feed into gluconeogenesis.

Clinical Significance

The pathology associated with glucose often occurs when blood glucose levels are either too high or too low. Below is a summary of some of the more common pathological states with associations to alterations in glucose levels and the pathophysiology behind them.

Hyperglycemia:

Hyperglycemia can cause pathology, both acutely and chronically. Diabetes mellitus I and II are both disease states characterized by chronically elevated blood glucose levels that, over time and with poor glucose control, leads to significant morbidity. Both classes of diabetes have multifocal etiologies: type I is associated with genetic, environmental, and immunological factors and most often presents in pediatric patients, while type II is associated with comorbid conditions such as obesity in addition to genetic factors and is more likely to manifest in adulthood. Type I diabetes results from autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta-cells and insulin deficiency, while type II results from peripheral insulin resistance owing to metabolic dysfunction, usually in the setting of obesity. In both cases, the result is inappropriately elevated blood glucose, which causes pathology by a variety of mechanisms:

- Osmotic damage: Glucose is osmotically active and can cause damage to peripheral nerves.

- Oxidative stress: Glucose participates in several reactions that produce oxidative byproducts.

- Non-enzymatic glycation: Glucose can complex with lysine residues on proteins causing structural and functional disruption.[11][1]

These mechanisms lead to a variety of clinical manifestations through both microvascular and macrovascular complications. Some include peripheral neuropathies, poor wound healing/chronic wounds, retinopathy, coronary artery disease, cerebral vascular disease, and chronic kidney disease. It is imperative to understand the mechanisms behind the pathology caused by elevated glucose.[12][13]

High blood sugars can also lead to acute pathology, most often seen in patients with type II diabetes, known as a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state. This state occurs when there is a severely elevated blood glucose level resulting in elevated plasma osmolality. The high osmolarity leads to osmotic diuresis (excessive urination) and dehydration. A variety of clinical manifestations ensue, including altered mental status, motor abnormalities, focal & global CNS dysfunction, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and orthostatic hypotension.[14]

Hypoglycemia:

Hypoglycemia is most often seen iatrogenically in diabetic patients secondary to glucose-lowering drugs. This condition occurs, especially in the inpatient setting, with the interruption of the patient's usual diet. The symptoms are non-specific, but clinical findings such as relation to fasting or exercise and symptom improvement with glucose administration make hypoglycemia more likely. Hypoglycemia symptoms can be described as either neuroglycopenic, owning to a direct effect on the CNS, or neurogenic, owing to sympathoadrenergic involvement. Neurogenic symptoms can be further broken down into either cholinergic or adrenergic. Below are some common symptoms of hypoglycemia:

- Neuroglycopenic: Fatigue, behavioral changes, seizures, coma, and death.

- Neurogenic - Adrenergic: anxiety, tremor, and palpitations.

- Neurogenic - Cholinergic: paresthesias, diaphoresis, and hunger.[15]

Tying what we have learned about glucose together in a brief overview of glucose metabolism consider that you eat a carbohydrate-dense meal. The various polymers of glucose will be broken down in your saliva and intestines, liberating free glucose. This glucose will be absorbed into the intestinal epithelium (through SGLT receptors apically) and then enter your bloodstream (through GLUT receptors on the basolateral wall). Your blood glucose level will spike, causing an increased glucose concentration in the pancreas, stimulating the release of pre-formed insulin. Insulin will have several downstream effects, including increased expression of enzymes involved with glycogen synthesis such as glycogen synthase in the liver. The glucose will enter hepatocytes and get added to glycogen chains. Insulin will also stimulate the liberation of GLUT4 from their intracellular confinement, which will increase basal glucose uptake into muscle and adipose tissue. As blood glucose levels begin to dwindle (as it enters peripheral tissue and the liver), insulin levels will also come down to the low-normal range. As the insulin level falls below normal, glucagon from pancreatic alpha-cells will be released, promoting a rise in blood glucose via its liberation from glycogen and via gluconeogenesis; this will usually increase glucose levels enough to last until the next meal. However, if the patient continues to fast, the adrenomedullary system will join in and secrete cortisol and epinephrine, which also works to establish euglycemia from a hypoglycemic state.[16][5][17]