Introduction

The greater splanchnic nerve (GSN) is the largest of 3 paired sympathetic nerves supplying the abdominal viscera. Preganglionic fibers follow a unique course through the sympathetic chain and feed into the GSN. After descending through the thorax and piercing the diaphragm, these fibers terminate in the superior-most preaortic ganglia, commonly known as the celiac ganglia. The GSN broadcasts its postganglionic fibers to foregut organs by way of the celiac plexus. Clinically, the GSN is responsible for some cases of chronic upper abdominal pain. Surgical interventions exist for patients whose pain does not respond to traditional pharmacologic therapy.[1][2][3][4]

Structure and Function

The sympathetic tone provided by the greater splanchnic nerve has an overall inhibitory effect on the foregut. One major exception is the sympathetic excitation of the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla.[5][6][7] Sympathetic outflow from the greater splanchnic nerve causes all of the following:

- Alimentary canal: Inhibition of motility and secretions of the distal esophagus, stomach, and duodenum to the level of the major duodenal papilla

- Liver: Stimulation of gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, and glucose release. Glucagon from the endocrine pancreas enhances this effect

- Gallbladder: Inhibition of smooth muscle contraction and bile emptying

- Exocrine pancreas: Inhibition of pancreatic enzyme secretion

- Endocrine pancreas: Inhibition of insulin release, stimulation of glucagon release

- Adrenal medulla: Stimulation of chromaffin cells to secrete catecholamines

- Spleen: Sympathetic fibers contribute to the splenic plexus that innervates the splenic capsule and transduces the sensation of splenic pain

Nerves

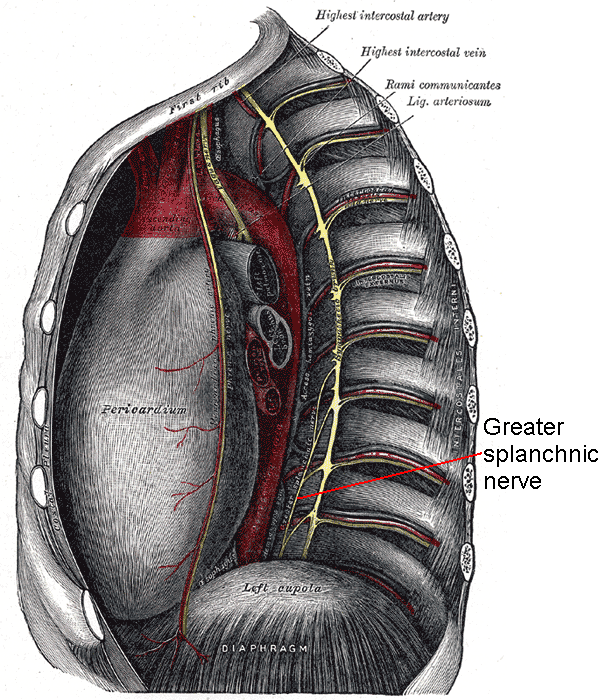

Many manuscripts describe the greater splanchnic nerve as a single anatomical structure, but they are bilaterally occurring nerves that run in tandem. These thick peripheral axon bundles carry both afferent and efferent fibers.

Efferent axons forming the basis of the GSN originate in the lateral gray horn of the thoracic spinal cord. These small diameter myelinated axons take a short course through the central nervous system (CNS) and exit with the ventral motor rootlets. Fibers contributing to the GSN classically arise from spinal levels T5-9, but several anatomical variations occur in humans. The autonomic fibers leave the vertebral column through intervertebral foramina with all other efferent and afferent fibers from a given level as spinal nerves.

The spinal nerves then separate into dorsal and ventral rami, allowing the sympathetic fibers to become their subsequent branch, known as the white communicating ramus. These white communicating rami feed into the sympathetic chain of ganglia that flank the vertebral column. The sympathetic chain extends along the entire length of the vertebral column from the cervical region superiorly to the coccyx inferiorly.

Unlike many other sympathetic fibers, the preganglionic axons of the GSN do not synapse in any of the sympathetic chain ganglia. Instead, all efferent contributions pass through the sympathetic chain, leave as branches, and consolidate into the greater splanchnic nerve. From there, the nerve travels inferiorly in the posterior mediastinum in close relation to the vertebral bodies. Along its thoracic course, the greater splanchnic nerves give small branches to the aorta before reaching the diaphragm. All three paired thoracic splanchnic nerves (greater, lesser, and least splanchnic nerves) pierce the lateral diaphragmatic crus at the vertebral level of T11 through a common foramen. Because all splanchnic nerves traverse the diaphragm together, there are generally collateral fibers that connect the GSN with the other nerves.

Upon entering the abdominal cavity, the GSNs turn 90 degrees medially and arrive at the ipsilateral celiac ganglion. The celiac ganglia are located on each side of the celiac trunk, a vessel that provides arterial supply to the foregut through its branches. Within these ganglia, GSN preganglionic fibers form cholinergic synapses with the perikarya of adrenergic neurons. Axons from these postganglionic neurons leave the celiac ganglia as a plexus that provides sympathetic innervation to the foregut. The postganglionic fibers radiating from the celiac ganglia contain less myelin than the preganglionic fibers and therefore convey information at a slower rate. As sympathetic nerves often do, the fibers from the celiac plexus tend to hitchhike along arteries to reach their effector organs.

In addition to its efferent course, the GSN also carries afferent information from the periphery back to the central nervous system. The transduction of pain from the foregut relies on small diameter myelinated fibers or unmyelinated fibers. Sharp pains tend to utilize small-diameter myelinated fibers, whereas dull pains tend to travel along unmyelinated axons. Visceral pain fibers arising from foregut organs travel with the celiac plexus fibers back to a synapse in the celiac ganglia. Their sensory axons follow the GSN back to the sympathetic chain. This afferent pathway utilizes the same white communicating rami, ventral rami, and spinal nerves to arrive at the dorsal roots of the spinal cord. Subsequent integration of sensory information into the spinothalamic tract allows visceral sensations to travel superiorly in the spinal cord anterolateral white matter to the cerebrum.

Physiologic Variants

Textbooks classically describe the greater splanchnic nerve with roots from T5-9, but other roots often join the nerve. Anatomists have observed T4 as the most proximal root and T11 as the most distal root. Some specimens have shown that the contributing roots are not always continuous and can sometimes skip spinal levels.

Additionally, these nerves are generally not bilaterally symmetric. Many cadaveric studies find that the right GSN originates higher in the thorax than the left GSN.

The three pairs of thoracic splanchnic nerves pierce the diaphragm through one common foramen, but they may run separately in a minority of specimens.

Clinical Significance

The greater splanchnic nerve is a target in the surgical treatment of chronic upper abdominal pain. Surgical interruption of the thoracic splanchnic nerves has proven effective in the management of pain in pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. The literature has also implicated splanchnicectomy as a potential option for treating patients with chronic spastic constipation, chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, and hypertension.

The French surgeon Pierre Mallet-Guy pioneered this operation with his laparoscopic work in 1943. He performed a bilateral transection of the distal thoracic splanchnic nerves below the diaphragm. Surgeons began accessing the GSN and associated nerves within the thoracic cavity for splanchnicectomies in 1990. A less invasive alternative to the open thoracotomy approach entered the literature in 1993 with reports of thoracoscopic splanchnicectomies. Several studies in the late 1990s interrupted the path of the GSN proximally with complete unilateral transection of the sympathetic chain. This riskier operation successfully palliated chronic abdominal pain, but it endangered the fibers of other vital sympathetic pathways within the sympathetic chain.

Video-assisted thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy (VATS) is now a common operative method for approaching the GSN and associated nerves. Insufflation of carbon dioxide induces partial ipsilateral lung collapse and provides space for the introduction of surgical instruments to the thorax. The GSN and its collaterals are located and transected. Some surgeons follow the GSN superiorly and divide all roots coming from the sympathetic chain. Others may track the GSN inferiorly and purposefully divide and/or cauterize it as close to the diaphragm as possible.

A 2008 systematic review of thoracoscopic splanchnicectomies highlighted the debate on the efficacy of unilateral versus bilateral transections. Surgeons who perform unilateral operations generally transect the left thoracic splanchnic nerves in cases of centralized or left-sided abdominal pain. Along the same lines, transection of the right thoracic splanchnic nerves is the approach in patients with predominantly right-sided pain. Nonetheless, some institutions prefer the bilateral division of these nerves because they feel this method achieves better pain control.

The majority of patients who undergo splanchnicectomy experience a significant reduction in their pain scores. Many patients eliminate their dependence on opioid narcotic medications following a splanchnicectomy. Upper abdominal pain that remains uncontrolled in a minority of patients following the operation may be due to anatomical variations in the GSN or extensive collateral formations with other thoracic splanchnic nerves.

Common side effects of the operation include increased bowel movements and orthostatic hypotension. The interruption of sympathetic innervation to the alimentary canal and adrenal medulla, respectfully, cause these side effects.

The effects of the operation typically wane over time. By 18 months post-operation, many patients experience as much pain as before their splanchnicectomy. Regardless, for patients with unresectable tumors, the operation has merit. Two-thirds of patients report that they would have a splanchnicectomy again.[8]